Letters, Spring 2021

Of Ballads and Baloney

In his wonderful article, (“Like Dreamers,” Winter 2021), Allan Nadler demolishes the fantastical claims that have been made for the Zionism of the Vilna Gaon and his followers. It bears repeating that early proponents of the Zionist idea nevertheless existed in religious circles, most notably Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795–1874) and Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai (1798–1878). The down-to-earth activities of like-minded individuals were highlighted 50 years ago in “The Ballad of Yoel Moshe Salomon,” by Yoram Tahar-Lev and Shalom Hanoch, which lyrically recounts (with poetic license) the founding of Petach Tikvah in 1878 by pioneers from the Old Yishuv of Jerusalem. Along with Salomon, the song mentions his colleagues Yehoshua Stampfer, David Guttman, and Zerach Barnett, as well as Dr. Mazaraki, a Christian physician and malaria expert. A version sung by the late Arik Einstein can be found on YouTube.

Yehudah Cohn

via email

Allan Nadler mentions Arie Morgenstern’s view that the Vilna Gaon’s support for Zionism was so well known that his disciples did not feel the need to record or mention it. This is reminiscent of the unresolved debate as to why Maimonides did not include living in Israel (yishuv Eretz Yisrael) in his list of 613 biblical commandments. The debates around the Maimonides case, however, are founded upon his specific writings. For example, in his 14 principles for counting the commandments, Maimonides explicitly excludes commandments that encompass the entire Torah. This suggests that yishuv Eretz Yisrael might be considered a “super commandment” under which all other commandments are subsumed. In any event, these discussions, unlike those regarding the Vilna Gaon, do not generally argue from silence.

Hillel M. Jaffe

Bronx, New York

The Singer or the Song?

Thank you so much for Dara Horn’s enlightening and somewhat disturbing review of Roald Dahl’s The Witches (“Who Doesn’t Love Roald Dahl?” Winter 2021). Years ago, troubled by the fact that so many of my beloved poets and authors were virulent antisemites, I wrote a lengthy question to a rabbi in which I asked: which is more important—the singer or the song? As adults, we are able to separate the two, but are we able to do so as children? How, therefore, do we respond as parents, if at all? Could I justify encouraging children to read the works of such a man or woman without giving insight into the person behind the works? I did not receive a definitive answer. Perhaps there is no definitive answer, but I was pleased that you too had shared my concern.

Carole Stock

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

The American Question

Steven J. Zipperstein’s review of I Want You to Know We’re Still Here: A Post-Holocaust Memoir (“At Home in America,” Winter 2021) recounts the many blessings of Esther Safran Foer’s life in America and then states that “amid all this joy, the shadows that haunt this memoir feel insubstantial.” I experienced the book differently. Safran Foer tells us of her searing discovery of a half sister who died in the Holocaust and whose name was forgotten, of her mother’s struggles with her horrible losses, and of her own resistance for many years to reading her father’s suicide note, while wanting desperately to find out if he loved her. I don’t think all the material success in the world would have made up for it if he hadn’t mentioned her in the note. I also felt that the frequent mention of her family’s success was important to her, a way of insisting that, as she says in the title, they are still here, a surprising achievement.

Although there are many ways in which America has been a good place for Jewish people, I think it would be a mistake to insist that there are not forces in play right at this moment that could change this. But is that really what the book is about? I think back to Esther with her collection of glass jars and plastic bags to hold bits of the past that could help explain it to her. This need for explanation and closure is what the book is about. And yes, I feel that it is extremely important to Esther.

Marlee E. Pinsker

Steven J. Zipperstein responds:

Marlee E. Pinsker and I read Esther Foer differently. I agree that all the details mentioned appear in the memoir, but these feel dim and distant against the backdrop of the buoyancy the author exudes regarding her remarkable family, her influential contacts, and the joy she expresses—rightly so—about the good life in America.

It is Pinsker’s criticism of my sense of the marginality of American antisemitism that may now seem off-target to some readers, particularly when viewed against the backdrop of QAnon’s heightened visibility and that of kindred forces of the far right. No longer can these be said to be confined to the netherworld of public life, now with one of its more media-savvy champions sitting in Congress.

Undoubtedly disturbing. But when brushed up against counterevidence, such shadows fade. By this, I mean the absence of any mainstream notice—certainly no annoyance—that the husband of the vice president, the Senate majority leader, the chair of the Senate’s budget committee, a sizable swath of President Biden’s new cabinet, the director of the CDC (our children went to the same Jewish summer camp), the lead lawyers on both sides of the latest impeachment hearings—all these are Jews. This is the America that Foer lives and thrives in, a far more accurate gauge of the rhythms of American Jewish life than the grim sight of January 6 rioters sporting Camp Auschwitz paraphernalia.

Against Artichokes

Given the season, I would like to turn your attention to David Stern’s interesting 2019 review of Shalom Sabar’s companion volume to a facsimile edition of the famous Sarajevo Haggadah (“Redemption in Catalonia and Bosnia: The Sarajevo Haggadah”). There, he surprisingly claims that there was a medieval Sephardi custom to use artichokes for maror at the Seder table. He supports this prickly claim with both textual evidence from rabbinic responsa and visual evidence in medieval illustrated haggadot.

However, the rabbinic authority cited, Abudarham (Seder ha-haggadah u-perusheha), states explicitly that the mandated custom is to eat lettuce. The mention of artichokes is only in a citation from a dictionary, Rabbi Nathan of Rome’s Arukh, in order to identify possible alternatives if lettuce is not available. The visual evidence is intrinsically subjective. According to Professor Marc M. Epstein, the illuminated image in the Sarajevo Haggadah and elsewhere more likely “depicts an entire head of romaine lettuce. The way to prove or disprove this would be to compare contemporary or roughly contemporary botanical manuscripts.” So, both of these sources are dubious, and this imaginary custom should be nipped in the bud.

Leor Jacobi

Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan

Books and Lives

Shai Secunda’s splendid review “(Almost) People” in the Summer 2020 issue brought me almost to tears with memories of my father, Samuel Weinerth (1916–2005), who grew up in a miserable, muddy village in the middle of Romania. He remembered his parents taking him, at three years of age, to the rabbi to lick honey off a volume of Talmud to teach him that learning Torah was sweet. For the next 10 years, he trudged through the snow to learn Talmud, layers of newspaper under his clothes for warmth, a handheld kerosene lamp lighting his way in the darkness, with an occasional escort of peasant children pelting him and other Jewish boys with stones. At 20, Talmud helped him endure sadism in the Romanian army and, later, it enabled him to survive forced labor in winter, digging in the frozen ground. Thank you for publishing this wonderful essay on the “intimate interrelations between people and books.”

Nora Weinerth

via email

Suggested Reading

The Secrets of the Efod

How did it happen that some of the most brilliant anti-Christian polemics of the late Middle Ages were written by an (at least public) Christian?

After the Fall

Who would have believed things could fall apart so quickly in Israel? And yet, Halkin writes, “I am in a way more hopeful than I was last December.”

The Mortara Affair, Redux

Bologna, 1857: A six-year old is taken from his Jewish family to be raised a Catholic. Why are we still talking about this case? An archbishop responds.

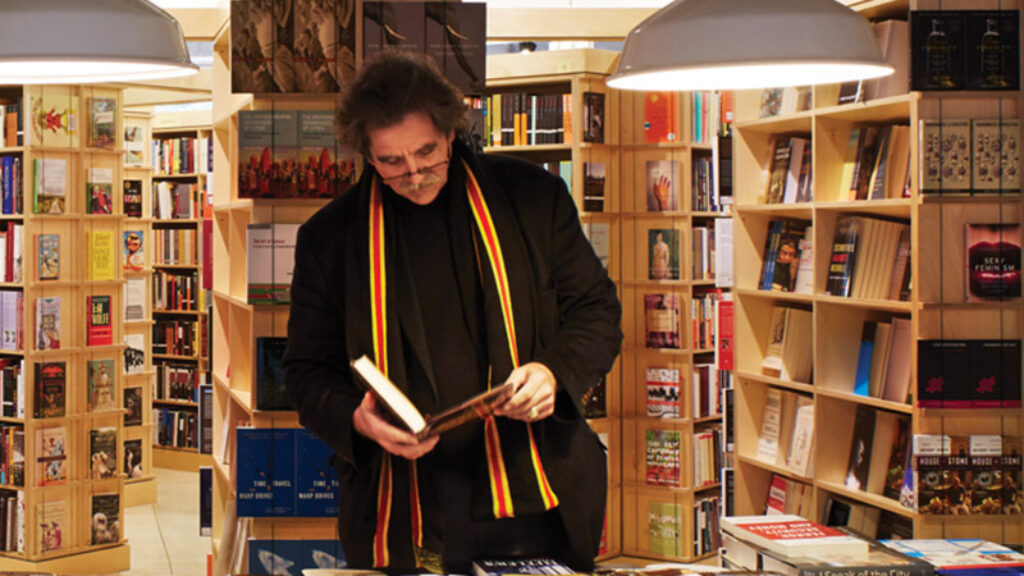

Bookstore or Beis Medresh

How I learned to stop worrying and love to browse.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In