More Important Things

I

cannot recall a literary debutante making as self-assured an entrance as Francesca Segal has made with The Innocents since Donna Tartt a generation ago. Yet The Innocents (which recently won the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature) is a more intellectually ambitious enterprise than The Secret History. Tartt played ingeniously with the conventions of the murder mystery, but Segal masterfully combines two contrasting fictional traditions: the Anglo-Jewish novel, as it has developed from George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda to Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question; and the Anglo-American novel, as it has developed from Anthony Trollope and Henry James to Martin Amis and Alison Lurie, in which the New World and the Old collide. The title and plot of The Innocents, in fact, pays homage to one of the finest examples of that genre, Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence.

To add to the technical accomplishment, Segal sees the temptation and fall of her protagonist, Adam, through his own eyes. This unfaltering assumption of a masculine persona lends additional significance to her epigraph, from Wharton’s The Age of Innocence: “In the rotation of crops there was a recognized season for wild oats; but they were not to be sown more than once.” Like Wharton’s Newland Archer, Segal’s Adam Newman is a magnificent evocation of young manhood, with its yearning both to belong and to break away.

Segal, not unlike many other aspiring young novelists, seems to have spent much of her twenties reviewing other people’s novels but failing to write her own. She is also the daughter of Karen and Erich Segal, to whom The Innocents is dedicated, though she has not allowed her U.S. publishers to make much of this fact. Many readers—especially those of a certain age—will nonetheless recall Erich Segal as the distinguished classicist and popular novelist who wrote the 1970s bestseller Love Story.

She was raised in the North Western Reform Synagogue in the Temple Fortune district of London, and an analogue to that congregation seems to figure prominently in The Innocents, though Segal has subtly disguised it. Women sit in a separate gallery, holidays are observed with great ceremony, but there is also room for adaptation and assimilation: One scene, for instance, takes place at a “Christmakah party.” Such an eclectic approach has its risks, but her anatomy of North West London Jewish life might not have been as richly authentic if it had been limited to any one community.

The Innocents opens with a Kol Nidre service, revolves around a wedding, and ends with a circumcision; custom and ritual punctuate the novel. These festivities enable the author to subject her living organism to merciless scrutiny, performing much the same function as Jane Austen’s seasons and balls. Geography is also cunningly deployed. Francesca Segal’s North West London (not to be confused with its near-neighbor, the North West London of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and NW) is a microcosm of the Jewish world, from Manhattan to Eilat. Beyond the bourgeois comfort zone of Hampstead Garden Suburb are the older, more religious denizens of Golders Green; other, more adventurous types have settled in the recently regentrified Georgian terraces of Islington or in the ethnic, religious, and sexual cauldron of the East End.

Ziva Schneider, a Holocaust survivor who made a new life in Israel only to end up in London, eating lunch every day at the Jewish Care survivors’ group, is the uncrowned queen of the novel. The memory of Bergen-Belsen casts a long shadow over the novel’s rites of passage: “I did not think I would or could ever again live in Europe and nothing can ever be certain,” Ziva tells Adam, as if to reinforce the symbolism of the Temple Fortune community’s name.

Ziva’s daughter-in-law has been killed by a Palestinian suicide bomber, leaving her son Boaz a grief-stricken wreck and her granddaughter Ellie Schneider a virtual orphan. When the novel opens, Ellie has just arrived from New York to find that her cousin Rachel has become engaged to her teenage sweetheart Adam. The triangular relationship between Adam, Rachel, and Ellie drives the narrative, but behind these twenty-somethings lies the inescapable influence of their three fathers. Two of them are absent: Boaz disappeared from Ellie’s life when she was 16, while Adam lost his father Jacob to cancer at 8. Only Rachel’s father is very much around. Lawrence Gilbert not only employs his prospective son-in-law but loves him, too. Adam knows this. Hence his sense of guilt and remorse at the idea of betraying Rachel is heightened by his boundless respect for Lawrence. Throughout, there is a tension in Adam’s mind between the two fathers, the living and the dead, the ersatz and the real. At the wedding, Adam can hardly bear his father’s absence, but later, at the circumcision, he realizes that only his own fatherhood can come close to healing that sense of loss.

His father should be here and was not; Adam had been angry for almost his whole life, he realized, always doing the right thing and meanwhile raging and resentful that no one saw the magnitude of that sadness . . . But something within Adam had shifted in that moment eight days ago when he had first held his son. No one could make it better. It could not be made better. But it could be made—bearable. If not acceptable then accepted. In moving on, he had then understood, in letting go, he was taking nothing away from Jacob.

Yet it is not Jacob, the ghostly father, but Lawrence the flesh and blood one, who has the last word. It is Lawrence who suddenly reveals his vulnerability when financial catastrophe strikes their law firm, but who also takes the younger man into his confidence and treats him as an equal. It is also Lawrence who senses the danger that threatens his daughter’s happiness and moves to protect Adam from his desire for the seductive but unattainable Ellie. And, in the final scene, it is Lawrence who, as family photographer, preserves for posterity the blissful moment when “the community would come to celebrate with them and to learn the name that they had chosen for their little boy, as he entered into this covenant of Abraham.”

If fathers in this novel are associated with a sense of the tragic, the mothers are left to provide the comic relief. And The Innocents is a very funny book, even if the mockery of the community is gentle rather than cruel. The account of Adam’s mother Michelle’s anxieties about the “bittersweet prospect” of her son’s marriage is a good example:

Somewhere out there is a shiksa with designs on her son. Jewish men make good husbands. It is the Jewish woman’s blessing as a wife, and her curse as a mother . . . but a nice Jewish girl, if she’s nice enough, holds deeper terrors. If she’s all that they dreamed of for their beloved boy, she might make the mother redundant . . . You never lost a daughter when she married. But Adam was the only man in her life.

For all its multilayered wisdom and wit, its satire and sense, The Innocents is at heart a love story. The most haunting character of all is Ellie, the femme fatale who lives in New York, which here functions as the very opposite of Edith Wharton’s citadel of convention. You don’t need to be very romantic to see why the repressed, dutiful Adam is attracted to this dangerous, damaged drifter. What is less obvious is why she falls for him, too. Ellie is touched by the fact that Adam is so ready to sacrifice everything for her. But her tender conscience and her vulnerability, the qualities that make him so protective of her, also make it impossible for her to steal him and thereby destroy the family’s happiness. By granting him a glimpse of life outside the ghetto, by affirming him sexually and emotionally, Ellie has given Adam’s life a three-dimensionality that it previously lacked, even if he may occasionally long for her and wonder what might have been.

Francesca Segal’s generous, garrulous, and utterly genuine group portrait of Anglo-Jewry may not have given the world a one-liner as memorable as her father’s “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” But, in The Innocents, she has done something harder: She has written a love story in which realizing that there are more important things in life than romantic love is sometimes the only action worthy of a man.

Suggested Reading

Sisters of Iron and Coders in Black Hats: Haredi Integration and the War Against Hamas

As Haredi men tie tzitzit for the IDF, and Haredi women volunteer to help soldiers, does their response to October 7th mark a turning point of integration?

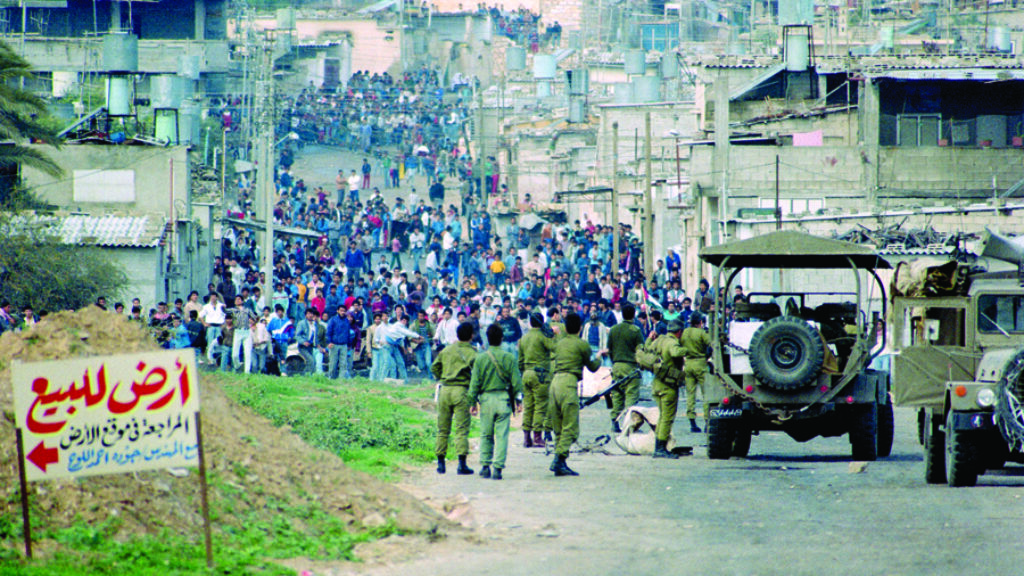

The Ethics of Protective Edge

How does one deal with Hamas, an enemy that has eliminated any trace of the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, except for the purposes of propaganda?

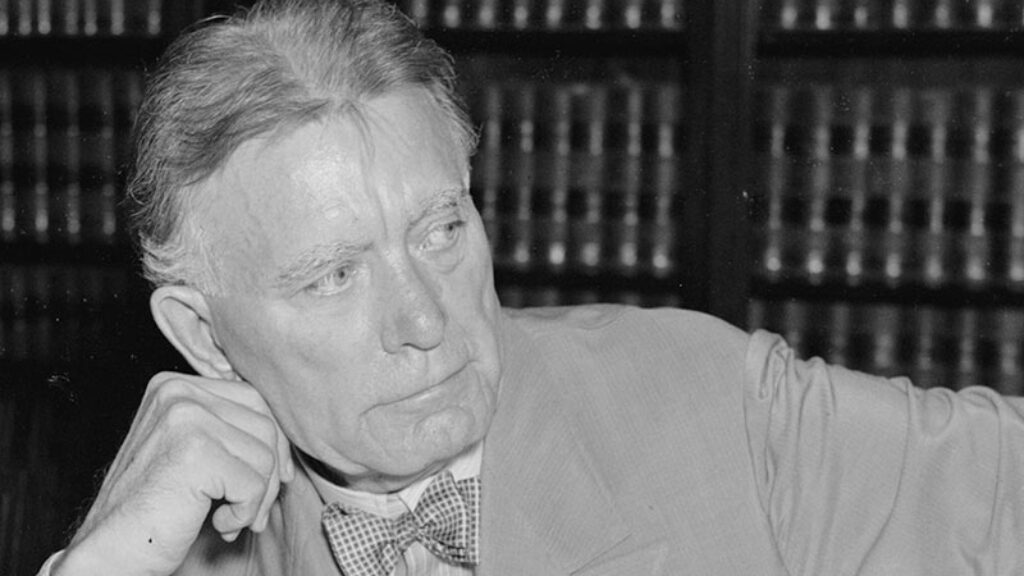

Horace Kallen, George Washington, and the Borah Affair

Was a quote from George Washington about isolationism real or fake, as Senator William Borah maintained, in a serious blow to Horace Kallen’s reputation?

Walkers in the City

Herman Melville was unimpressed with Jerusalem in 1857, but what would he say if he were a saunterer on Mamilla or King George today?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In