Horace Kallen, George Washington, and the Borah Affair

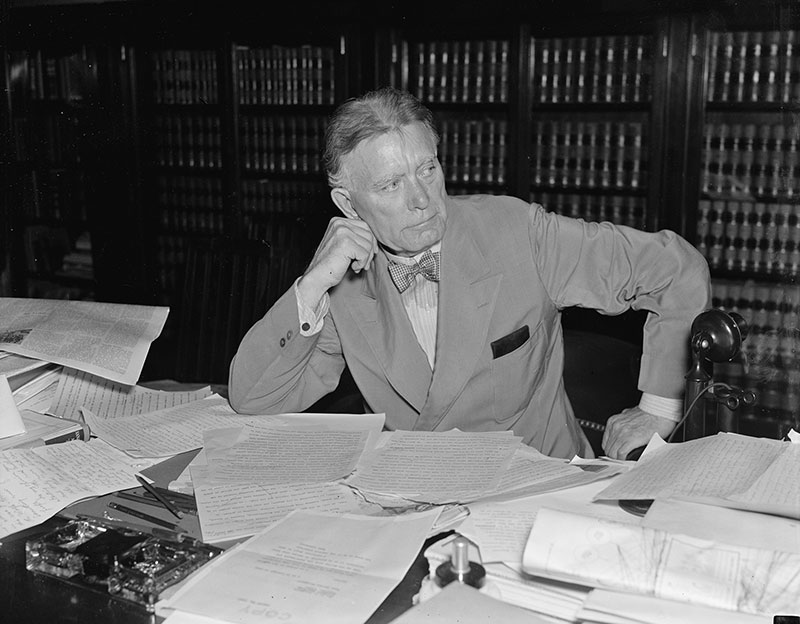

On February 2, 1934, Professor Horace M. Kallen received a letter from H. H. B. Meyer of the Library of Congress asking for the source of a quotation. Thirteen years earlier, Kallen had published an article arguing for the legitimacy of the League of Nations in which he had quoted George Washington as saying, “When, our institutions being firmly consolidated and working with complete success, we might safely and perhaps beneficially take part in the consultations held by foreign states for the advantage of the nations.” Meyer’s note was brief and courteous; he even enclosed a stamped envelope to save Kallen postage. What Meyer did not disclose was that, as director of the library’s Legislative Reference Service, he was writing at the behest of Senator William E. Borah, Republican of Idaho and the Senate’s most prominent isolationist, who was convinced that the quotation was spurious and demanded to know the source.

Borah, who was the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, had seen the quote in a recent Washington Post editorial that criticized his use of a more famous quotation from Washington regarding foreign entanglements, words he’d been quoting ever since President Wilson had returned from Europe with the Versailles Treaty. In his Farewell Address, Washington had said, “The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible.” Borah was aghast when the Post, citing the “dynamic character of a changing civilization,” had quoted George Washington advocating internationalism to undermine Borah’s isolationism. The Library of Congress, asked to find the source of the suspicious quotation, discovered it in a book by historian George Blakeslee, and Blakeslee led them to his source: Kallen.

Meyer had to write to Kallen again three weeks later before receiving a response of sorts. It came from Kallen’s secretary, Madlyn Miller, who wrote that not only did Dr. Kallen not have the article on hand, he didn’t even remember it. Moreover, she reported that Kallen’s files from 1921 were unavailable, and his secretary from those days was no longer in his employ. This was technically true; Kallen was no longer employing that secretary, but he was living with her. She was his sister, Frances, who had lived and worked with him in his early years at the New School for Social Research. By the time Kallen heard a second time from Meyer, Frances, now a hospital administrator, was probably already ill with the disease that, eight weeks later, would end her life at age 36. With Frances declining and Meyer’s query answered (after a fashion), Kallen let the matter rest. It is true that Kallen, who was an ardent Zionist, a prominent internationalist, and the leading advocate of what he called “cultural pluralism,” had written dozens of articles over the past 13 years (indeed, he’d published five books) and might have forgotten a piece in the Journal ofInternational Relations. Still, the response of his secretary was odd; it read like a deflection.

That might have been the end of it, but a year later, on Washington’s Birthday, Borah took to the Senate floor. After the customary reading of Washington’s Farewell Address, Borah had the Post’s harsh editorial read into the Congressional Record along with Madlyn Miller’s letter and then furiously denounced the unsourced quotation of Washington as a “crude, clumsy, impudent forgery”:

It carries the brand of criminal falsehood upon its face. In style, in manner of expression, in substance, and in thought, it is manifestly a weak but vicious pretense. . . . It was forged for a purpose; that purpose was to plant in our historic literature a view contrary to all views expressed and opinions entertained by the Father of his Country.

In the year since the editorial had appeared, Borah announced, a cadre of eminent historians had certified that the quotation was spurious. With a flourish, Borah announced that he had at last traced the offending quote to Horace M. Kallen.

Senator Borah had probably already been aware of Kallen, at least as a prominent academic advocate of the League of Nations (Kallen had written two books supporting it), which the senator had vociferously opposed. Borah, who was one of the “Irreconcilables” determined to block ratification of the Versailles Treaty in 1919, had said, “If the Savior of mankind would revisit the earth and declare for a league . . . I would be opposed to it.” Sixteen years later, when the question of America’s involvement with Europe was once again coming to the fore, a suspicious quote from “the Father of his Country” about participating in “consultations held by foreign nations” cried out for refutation.

Kallen didn’t learn of Borah’s yearlong crusade to expose him as a clumsy, criminal, impudent forger bent on planting an alien graft into “our historic literature” until the senator’s denunciation from the Senate floor made the news. “I am mad as hell about it,” Kallen wrote to his brother-in-law, Fred Blachly, a political scientist at the Brookings Institution, “but I have got to find the source of the quotation.”

In mid-March, historian George Blakeslee, who was also the founder of the journal in which Kallen had published his now controversial article, suggested, correctly, that Kallen’s source had been Edwin D. Mead, former director of the World Peace Foundation. However, that didn’t help much because Mead, in turn, had cited an 1898 Atlantic Monthly article by Richard Olney, Grover Cleveland’s secretary of state, who had described the source of the Washington quote merely as “an authority of the highest character.” So, who was that? The answer, Blakeslee suggested, might lie with one Miss Straw, the secretary who had taken “this Atlantic Monthly article from Mr. Olney’s direct dictation.”

Meanwhile, editorials with such titles as “An Impudent Forgery” appeared in Hearst-owned papers. This was hardly a surprise; Hearst had been boosting Borah’s isolationism since 1919. Kallen, working through the growing pile of denunciatory clippings from newspapers throughout the country, began to realize just how damaging Borah’s attack had been. He wrote to his friend, Denys Myers:

The repercussions among the reactionaries, patrioteers, “isolationists” and others continue to develop. The damage which Borah has done is in some ways irreparable because it is impossible to catch up with a lie.

He intended to sue “Hearst’s whores”—“the whole jackal press of the country”—for libel. But what was to be done about Borah? Was it wise, Kallen wondered, to demand an apology from the senator before learning the source of Olney’s quotation?

This was the era of slow scholarship. For almost two years, researchers, most of them women—a sister, a sister-in-law, an aged secretary, women executors, and longtime women friends—were sent to burrow through libraries, archives, and uncollected manuscripts (all without remuneration) in search of the fugitive lines. In late March, Kallen still had no answers. Impatient to act, he drafted an angry letter to Borah and showed it to several friends, who advised him to tone it down.

He also enlisted help from Rabbi

Stephen Wise, who knew Borah personally. “He is a very evasive person,” wrote

Wise, “as shown in his conduct when, despite his promise to me, he opposed

Brandeis’s confirmation.” (In fact, Borah had been one of the 27 senators of

both parties who had simply declined to vote on the first Jewish nominee to the

Court—

a choice, to be fair, that he later regretted.) In his letter to Borah, Wise

listed Judge Julian Mack, Associate Justice Louis Brandeis, then Harvard Law

professor Felix Frankfurter, and philosopher Morris R. Cohen as prominent

friends of Kallen. Knowing that Borah prided himself on his credentials as a

progressive Republican, he also mentioned “the older and younger Senators La

Follette and Governor La Follette.”

It did not escape Borah’s notice that, except for the La Follettes, all of these associates were Jews. Denying that he had “even inferentially charged Professor Kallen with forgery,” Borah informed Wise that “since receiving your letter I have submitted my statement in the Record to a friend who is also a well-known person of your race, and asked if he placed any such construction upon the statement. He stated emphatically he could see no legitimate inference of that kind.” Borah’s Jewish referee may well have been peace activist Salmon O. Levinson, an attorney who had worked closely with him on passing the Kellogg-Briand Pact outlawing war. Because the toothless pact did not compromise US sovereignty (since any act of provocation immediately dissolved it), Borah had strongly supported it, and, in January 1929, the Senate ratified it by a vote of 85–1. Whoever the Jewish referee was, Borah’s letter implied that Wise would only be convinced by the views of someone “of your race” and signaled that Borah would not be impressed or intimidated by a clutch of eminent Jews—one of whom he had effectively rejected for the Supreme Court. Borah was clearly peeved by the implication that a whiff of antisemitism hovered over Borah’s charge that the “impudent” Kallen had planted a foreign element in “our historic literature.”

Kallen’s response to Borah began on March 29, 1935, with a four-page letter copied to the Washington Post. He cited Mead’s two speeches and Olney’s article, noting, “As is customary among gentlemen and scholars, I took for granted that when a man of Mr. Mead’s standing quoted, he quoted honestly, fully believing that those words expressed the very view of George Washington.” To Kallen’s request for a retraction, Borah responded, as he had to Rabbi Wise, by denying any wrongdoing. Unmoved by Kallen’s reference to gentlemen and scholars, Borah declined to do anything “until you are prepared to state either that you regard the quotation from Washington as correct or incorrect.”

Kallen responded by saying that he would be forced to “publish this correspondence in the press” and mailed 51 copies of the letters to national daily papers such as the New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune, weeklies such as Time and Newsweek, wide-circulation magazines such as the Atlantic Monthly and Esquire, scholarly journals such as Foreign Affairs and the American Historical Review, regional papers such as the Baltimore Sun and the Kansas City Star, leftist magazines such as the New Masses and the Daily Worker, and the Jewish press, including the Forvertz and Der Tog, alerting them to expect antisemitic responses. The upshot of this flurry was . . . not very much. Although scores of polite notes drifted in, no one offered to publish the correspondence, and only a few small papers published editorials. Several editors wrote that the compilation was both too long and unamenable to excerpting. And for many, one intractable question loomed over the whole affair—Borah’s question: Had George Washington written this or not? Kallen’s negative press, however, continued: typical was a Chicago Tribune smear called “Falsifying History.”

Kallen’s ace in the hole was the Washington Post—or so he thought. On April 13, after lecturing at Howard University alongside W. E. B. Du Bois, E. Franklin Frazier, and Ralph Bunche, Kallen met with Post editor Felix Morley, who revealed to Kallen not only that he himself had written the January 1934 Post editorial but also that he had cited Washington’s supposed words in his 1932 book, The Society of Nations. With Morley’s “own scholastic reputation . . . involved in the dispute,” he was planning to soon publish the Kallen-Borah letters on the editorial page, on successive days, each with an editorial headnote. But on April 29, Kallen had still not seen the letters in print. He wrote Morley asking if the letters might be brought out as a pamphlet; the archive holds no reply. The decision to kill the story was probably not Morley’s. Two years earlier, near bankruptcy, the Post had been scooped up by Eugene Meyer, former Fed chairman under Hoover, descendant of Alsatian Jews. Although Meyer had vowed to keep the paper nonpartisan and independent, he was a prominent Republican. Taking on Borah might have been too much, especially with rumors flying that Borah intended to run for the Republican nomination. When Borah announced his candidacy on December 20, 1935, the Post welcomed it with an editorial.

Toward the end of April, Kallen received a letter from Antoinette M. Straw, the secretary who had taken dictation for Richard Olney’s article in the Atlantic. She had been hoping to search Olney’s scrapbook from 1898, but, maddeningly, “that particular volume of our collection was sent to Mrs. Minot at Falmouth three or four years ago to look over and she has not yet been able to lay her hands upon it. She will find it presently I am confident.” But Straw also suggested that Olney might have seen the quote in official State Department documents. She was right. In Olney’s papers, the quotation was traced to a letter from William Seward, Lincoln’s secretary of state, to William Dayton, minister to France, dated May 11, 1863. Ironically, whereas Kallen had been ready to trust Secretary of State Olney, Olney had not extended the same favor to his predecessor, Seward, continuing to hunt for the source. Coming up empty, Olney had used the quotation anyway.

Soon, Kallen learned that Senator Elbert D. Thomas (D-Utah), a Japanese-speaking Mormon internationalist, was gathering materials for an anti-isolationist Senate speech on Washington’s Birthday. When Thomas failed to deliver the speech, Denys Myers mused to Kallen that perhaps Thomas didn’t want to take on his senatorial colleague now that he was a presidential candidate. A year later, however, on February 22, 1937, Thomas did deliver his speech after the ritual reading of Washington’s Farewell Address. Recalling Borah’s denunciation “on this floor two years ago today” of the “crude clumsy, impudent forgery” of Washington’s views, Thomas wryly observed that “Washington is quoted much as Shakespeare has credited the devil with quoting his Scripture, ‘for his own purpose.’” Citing Washington’s call for “the adoption of a proper Peace Establishment,” Thomas wrestled Washington away from Borah, taking him back for the cause of internationalism:

For Europe it is collective action or continued fear, dread, and uncertainty. . . . Can the world continue the master contest based upon fear, distrust, and force, or shall it turn to the sobering advice of a Washington, whose spirit speaks to us today from between the lines of his words uttered in 1783?

Borah took to his feet in disgust, insisting that “those who asserted this language to be in Washington’s address . . . were impudent forgers and nothing less.”

Having lost his 1936 bid for the Republican nomination, Borah spent the late 1930s pressing the case for American neutrality. He habitually blamed the Versailles Treaty for Hitler’s aggression. Privately, Borah also lamented Nazi persecution of “those poor people” and criticized Germany for financing insurgents in the United States. But he made no secret of his admiration for Hitler, imagining that a personal conversation with the Führer just might set things to right: “There are so many great sides to [Hitler], I believe I might accomplish something.” In 1938, he sought, through the German ambassador, an invitation to Berlin. But when the Foreign Office cabled the invitation to meet with both Hitler and von Ribbentrop, Borah declined; he was ill, relations between the United States and Germany were deteriorating, and he suspected FDR would block his journey. Upon learning that Germany had just invaded Poland, Borah told a journalist, “Lord, if I could only have talked to Hitler—all this might have been averted.” Meanwhile, despite Stephen Wise’s personal appeals, Borah refused to speak out against the Nazi persecution of Jews. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in January of 1940 with two great political regrets: not voting for Brandeis and not meeting Hitler.

By the late 1930s, watching the Nazis rise to power, Kallen had shifted his focus from internationalism to intervention. He spent the 1930s organizing the New School’s University in Exile for academic refugees from Nazi Germany, boycotting German goods and academic conferences, and protesting to the Japanese government about antisemitism in Manchuria; he also denounced the DAR as a fascist organization. Barnstorming from city to city, Kallen gave a rousing speech called “The Assault on Democracy,” urging his audience to protest neutrality and aid refugees. In 1935, he became chair of the World Jewish Congress’s committee against antisemitism and, two days after the passage of the Nuremberg Laws, spoke about antisemitism to an audience of over three thousand in Carnegie Hall.

As early as 1936, Kallen had voiced his eagerness for someone to write a long article about his controversy with Senator Borah focused on the senator’s “disingenuity and cowardice.” Senator Thomas’s 1937 speech, despite taking Kallen’s side against Borah, had neither vindicated Kallen personally nor advocated for action against Hitler. More than a year after Borah’s death in the spring of 1941, a massive article, “George Washington and the Isolationists,” appeared in the New Leader in four installments by the previously unknown Warrell Gainsborough. Of course, by that time, the possibility of American neutrality was close to a dead letter. When the entire article was published as a pamphlet in early 1942, Pearl Harbor had been bombed, and the US was at war. Nonetheless, Kallen had finally received his vindication—but from whom?

Who was Warrell Gainsborough? Apart from citations to the article and subsequent pamphlet, as far as Google, the Ancestry.com database, WorldCat, the Archive Finder, and the ProQuest Historical Newspapers database are concerned, he never existed at all, not as such. To add to the intrigue, I found the original manuscript of the article in Kallen’s papers at the American Jewish Archives. (The typescript is there too.) The manuscript is not written in Kallen’s distinctive hand, although the many corrections and emendations were clearly written by Kallen. As one might expect, the article is also extremely sympathetic to Kallen. So, the question is not “Who was Warrell Gainsborough?” but, rather, “Warrell Gainsborough was . . . whom?”

In pursuit of an answer, I consulted the archives of the New Leader. While they hold no Gainsborough folders, they do hold two folders of letters between Kallen and editor Sol Levitas. The first contains a cover letter dated February 27, 1940, for “the manuscript I mentioned over the telephone,” asking for “reprints of the whole thing for wide distribution.” Their correspondence has a cloak-and-dagger feel to it: Kallen will only discuss the manuscript in detail on the telephone, and it is the only one of Kallen’s many cover letters to Levitas not to give the title or topic of the piece. In a follow-up six weeks later, Kallen asks, “What has happened to my mss?” failing to mention its supposed author (whose initials, if you reverse them, happen to be the same as those of George Washington). “If you are not going to use it,” Kallen wrote to Levitas, “don’t be afraid to tell me so and return it to me. I can well understand the difficulties of the situation.”

A year later, Kallen reminded Levitas about the desired reprints, requesting that his letters to Borah, as well as press clippings, be appended. Apparently, Kallen was footing the bill, since he also asked for prices for printing 1,500 copies with and without appendices. That May, the pamphlet was listed in the New York Times Book Review under Gainsborough’s name with 66 W 12th Street given as the author’s address, but, when the New York Public Library tried to contact the author at that address, their letter was returned; it was Kallen’s work address at the New School, whose mailroom clerks had no knowledge of Warrell Gainsborough. When Levitas forwarded the library’s query, Kallen reached for the phone, as he had when he’d first proposed the manuscript to Levitas: “I gave your girl the answers to your questions of November 14 over the phone,” he wrote cryptically, noting that he had on hand many copies of the pamphlet and would be “happy to distribute them.”

Whoever Gainsborough was, it wasn’t Kallen himself; neither the handwriting nor the style matches his. Kallen’s writing is quirky and florid, given to elaborate metaphors; his vast range of reference borders on the preening; his argumentation is often obscure. Gainsborough’s style, by contrast, is fluent but disciplined. So, who? Kallen’s range of acquaintances was vast, and he had access to a healthy supply of fledgling journalists and hungry graduate students; he also had funds at his disposal to compensate the writer. I have compared the Gainsborough manuscript with the handwriting of several possible suspects—including lawyer-philosopher Milton Konvitz; Kallen’s brother-in-law, Fred Blachly; his sister, Miriam Kallen (a teacher and future professor of education); and activist Fola La Follette—and failed to find a match. One thing is clear: whoever Gainsborough was, Kallen did his best to make sure we wouldn’t find out. (Since biographers “dwell in possibility,” I carry a handwriting sample in my wallet against the chance that, someday, late in the afternoon in a dusty archive, I’ll find a match.)

What “Gainsborough,” whoever he or she was, accomplished was to take a 20-year-old controversy about Washington’s legacy for foreign affairs and refocus it sharply. Back in 1921, while Borah and the “Irreconcilables” paraded under the banner of an isolationist Washington, Kallen had claimed the first president for the cause of internationalism. In 1935, Borah had declared, on the floor of the Senate, that this internationalism was not merely a misreading; it was “a deliberate forgery,” the intellectual equivalent of fifth-column subversion.

It was now 1941, and given Kallen’s activism on behalf of Europe’s Jews, one might expect Gainsborough to cherry-pick passages casting Washington as an interventionist or, at least, as a protector of human rights. Instead, Gainsborough emphasized Washington’s apprehension about the viability of the United States, for it was national unity—not federalism—on which the independence of the country would rest. In other words, at the time Washington wrote, “If we remain one people, under an efficient government” in his Farewell Address, national unity was a very big “if.” Washington’s objection to foreign entanglements, Gainsborough asserted, was to forestall foreign countries—France in particular—from “tamper[ing] with domestic factions”; “foreign influence,” Washington wrote, “is one of the most baneful foes of republican government.” What had alarmed Washington was not foreign entanglements per se but covert operations at the highest levels of power—in this case, both backchannel negotiations between Secretary Edmund Randolph and the French ambassador, Jean Antoine Joseph Fauchet, and an attempt by Fauchet’s successor to tamper with the 1796 election. Gainsborough claimed that the Farewell Address called not for “a permanent policy of Isolationism, but isolation until our country was united and strong,” after which it would be free to consider both its interests and its principles in making decisions on foreign policy, which was precisely what was expressed in Kallen’s quotation of Washington, authentic or not.

When the Borah affair commenced, Kallen was a distinguished professor in his early fifties with a Rolodex full of journalists, editors, scholars, editors, clergy, civic leaders, attorneys, and politicians. It was a pluralist’s Rolodex: people ethnically and regionally various, from all walks of life. Many were individuals of prestige and power. But one lesson of the Borah affair for Kallen was that damage to a reputation, when caused by a man of prestige and power, was almost indelible. Borah’s characterization of Kallen as an impudent forger scarred Kallen and made him desperate, perhaps too desperate, to locate the elusive quotation and vindicate himself, at a moment when he needed all of his public credibility to press the case for America’s international responsibilities in the run-up to World War II. What he learned is a lesson those in American political life go on learning: “it is impossible to catch up with a lie.”

Suggested Reading

America’s Jewish Bridegroom

Horace Kallen can be found in the ill-starred pantheon of prolific writers known for only one thing: one novel, one sonnet, one treatise, or, in his case, one idea. That idea is “cultural pluralism.”

Old Isaiah

When Woodrow Wilson became the first president to nominate a Jew for a seat on the Supreme Court, much of the opposition to his appointment revolved around his Jewishness.

In the Melting Pot

More than a century after Zangwill's play debuted, the melting pot is still bubbling. What does that really mean for American Jewry?

When Everything Matters

Bellow on Roth on TV.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In