Sisters of Iron and Coders in Black Hats: Haredi Integration and the War Against Hamas

In a small room in the Gur Yeshiva of Arad, six Gur Hasidim wearing traditional long black bekeshes stand in front of wooden makeshift desks, tying the knots of tzitzit with extraordinary dexterity and speed. A traditional Shabbat song is blaring: shamor l’kad’sho mibo’o v’ad tseito (be sure to sanctify it from start to finish). While the tzitzit are typically white, these are army green. For a community whose members do not serve in the Israeli Defense Forces and whose official ideology remains anti-Zionist, this moment, and innumerable others like it throughout the Haredi world in the weeks since the Hamas massacre, may mark a turning point in Haredi integration into Israeli civic culture.

I spoke with Chana Irom, who describes herself as “mainstream Jerusalem Haredi.” Irom is a community activist whose essays have been published in leading ultra-Orthodox publications. Irom is the founder of Sisters of Iron, a Haredi women’s volunteer organization established immediately following the Hamas massacre to help female relatives of soldiers and captives. Their organization is headquartered in a sheitel shop called Wig Box, in the religious neighborhood of Sanhedriya. Irom has six volunteers working every day to receive or make personal phone calls to women in need, and to collect information for distributing hot meals, babysitting, and home visits. “Some women just need to talk,” she says.

In the process of scaling her initiative, Irom was contacted by Bonot Alternativa, Building an Alternative, a left-wing Israeli social activist organization that seeks to promote social equality and raise awareness of violence against women. The group’s red costume with a white bonnet—a nod to the uniforms forced in Margaret Atwood’s patriarchal dystopia The Handmaid’s Tale —is worn weekly by members protesting in front of the Prime Minister’s residence. Irom says she asked a leading Haredi rabbinic authority whether it was permissible to collaborate (personally, not politically) with an anti-religious group and received his blessing. Borrowing a metaphor from the Book of Genesis, Irom says that she hopes initiatives like hers can create a new beginning out of the political chaos and horror of the last year.

Last year, Ori Eisenberg helped found Kodcode, a program that teaches math, English, and computer programming to young, mostly married Haredi men so that they can enter IDF’s elite cyber or signal intelligence units. In July of this year, eighty-eight of its applicants were recruited to the military and within the first week of the Gaza war there were 750 new applicants. “The barrier to integration which used to be identification with the state, especially the army and its symbols, are now seen in a completely different light,” says Eisenberg. “If both the military and the Haredim are flexible, both stand to gain. It’s a win-win situation.” Tragically, Kodcode’s director Major (res.) Moshe Leiter, 39, was killed in battle last week in Gaza.

As of early November, IDF spokesman Daniel Hagari disclosed that 2,000 Haredi men have expressed a desire to enlist in the military, despite the de facto exemption of Haredim from military or national service that has been central to the political controversies of the last year. Although this is a grassroots development, Rabbi Refael Kroizer, Dean of Lemaan Daat, is one prominent Haredi rabbi who has been among the voices calling for enlistment, saying two weeks ago that “Our people are in danger. . . . It is incumbent upon us to be there in practice, with true devotion, and to put our lives on the line.” Still, most mainstream Haredi rabbis have remained silent about such initiatives, or have opposed them outright. Rabbi Dov Lando, Rosh Yeshiva of Slabodka in Bnei Brak and a towering figure in the Haredi world, published a letter on October 31 consistent with classic Haredi political theology, calling on his adherents who have joined the war effort to instead “return to God.”

Despite the voices of dissent, Nechumi Yaffe, a public policy professor at Tel Aviv University and head of the Tatia Haredi think tank is optimistic, calling the war a “moment of awakening” for the community to take part in Israeli civic society. According to Yaffe, Haredim no longer want to feel estranged from the Israeli narrative. Yaffe’s team conducts weekly polls of Haredi attitudes toward the State and, though cautious, she is hopeful that the community’s interest in both the workforce and military will persist beyond the war.

Kimmy Caplan, a professor at Bar Ilan University who studies modern religious history and trends is skeptical that the current Haredi volunteerism portends a change in Israeli society. Rather, the Gaza war is “another tectonic event in which Israelis from all sectors are responding in abnormal ways,” and they are likely to return their normal patterns of behavior and belief once the crisis is over.

Of course, Caplan may well be right, but the current initiatives accentuate long-term trends. And right now it is hard to imagine that the grassroots mobilization of the Haredi society isn’t part of a long-term reshaping of Israeli society.

Suggested Reading

Jerusalem Reconstructed

The Mendelsohns' converted flour mill on the outskirts of Rehavia became a cultural salon, with concerts and poetry readings.

At the Anti-Israel Carnival

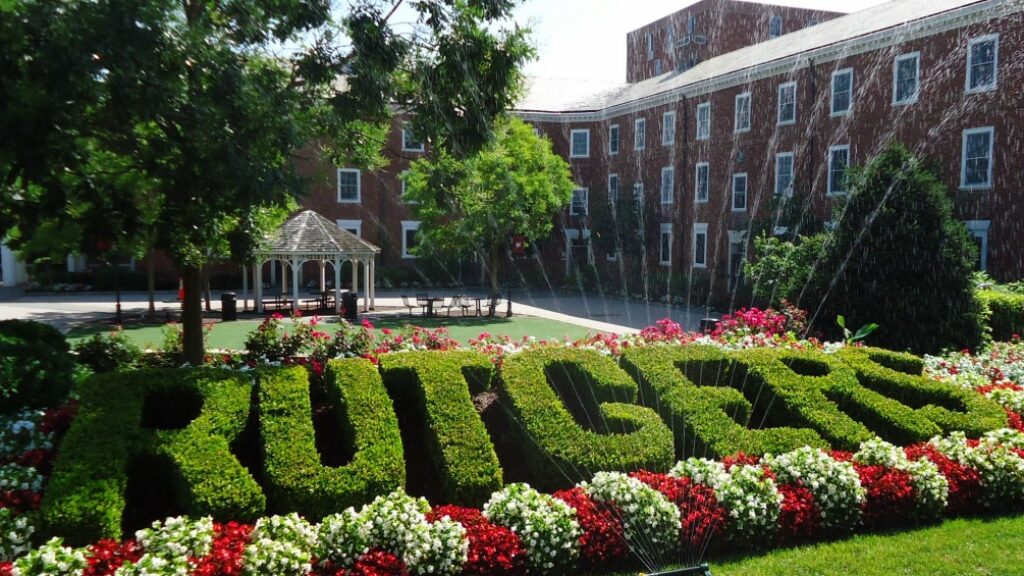

Students at Rutgers University protest Israel like they're attending a carnival. A professor explores the troubling scenes she's witnessed—and rereads Mikhail Bakhtin.

Inconceivable

Two new books push readers to examine the phenomenon of childlessness in the Jewish tradition and modern Jewish life.

Crazy Rich Sephardim

For a time, Shanghai soared along with these unusual Ottoman Jewish émigrés, the Sassoons and the Kadoories.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In