From Russia with Complications

In the late 1950s, when I was in Israel for an extended stay, a stranger showed up at my apartment on Gaza Road in Jerusalem. I was in bed running a high temperature, but that did not prevent him from firmly pushing my wife aside and barging into my room, where he pummeled me with questions. Introducing himself only as Shaul, he told me that his boss, David Ben-Gurion, had learned that I had made several research trips to Russia in the past few years, which was unusual in those days. If a massive effort were undertaken to get the Jews out of Russia, Shaul had been commissioned to ask me, how many would come? How much would such an effort upset the Soviet leaders? And could I suggest a few people who might be suited to help get the process started?

My visitor, a blunt man, did not hide his doubts: It was not quite clear to him what a Jew of German origin (he used the more pungent term yekke) could possibly have to say about the Soviet Union that someone like him (he was born in what was then the Russian empire on the last day of the 19th century) did not already know. Whether, in my feverish state, I told him anything that dispelled his doubts, I do not exactly recall, nor is it of historical importance whether anything I said played a role in the subsequent deliberations. I do know that some of the people I named became active in the clandestine campaign that was subsequently undertaken, including the British writer Emanuel Litvinoff, who died two years ago in London, at the age of 96.

May 2012. (© AP Photo/Oded Balilty.)

In the years that followed I occasionally encountered the legendary Shaul Avigur and those working for him, both in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, and I was impressed by their efforts against heavy odds. I couldn’t help thinking of them, and their great contributions to the awakening of Soviet Jewry in the 1950s and 1960s, as I read Lili Galili and Roman Bronfman’s path-breaking new book about the Russian aliyah of the last two decades. Avigur and his associates did their dangerous work long before the events described in the third chapter of this book (“How It Began”), but they laid the indispensable foundations for the post-Six-Day War aliyah, as well as the more massive exodus that commenced in the late 1980s after a regrettable hiatus. Had it not been for these cloak-and-dagger heroes, who knows whether there ever would have been a Sharansky or any refuseniks at all?

Galili, a well-known journalist who for many years covered the Russian immigrant beat for Ha’aretz, and Bronfman, a Russian-born former community activist and member of the Knesset, have produced the first study of the latest and largest wave of migration out of the Soviet Union. With what is probably only a slight exaggeration, they have titled it Ha-milion she-shina et ha-mizrach ha-tikhon (The Million that Changed the Middle East). Israel’s leaders had high expectations with regard to this aliyah. Although they were eager at all times to increase the state’s Jewish population by any means, they viewed the Soviet Union’s long-captive Jews as particularly desirable “human material,” people who would not only help to offset the Arabs’ higher birth rates but would add countless scientists and engineers to Israel’s labor force. Fearful of this augmentation of Israel’s strength, the Palestinians and other Arabs brought pressure on Moscow to stop the Jewish aliyah, but their efforts led nowhere.

Where they failed, however, America was unintentionally, albeit briefly, successful. In the late 1980s, when the mass migration was just beginning, the prospect of economic opportunity and security in the New World lured the large majority of Soviet Jewish émigrés away from the land of their fathers. “In 1989,” Galili and Bronfman tell us, “when emigration in meaningful numbers first became possible, the drop-out rate in Vienna,” where there was a fork in the road that led to the United States, “was more than eighty-three percent, a powerful contradiction of Israel’s Zionist-demographic dream.” It was only after Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir persuaded Washington to limit the entry of Russian Jews into the United States that the flow of immigrants changed directions. As an Israeli minister put it at the time, “This was cruel Zionism, if one can say such a thing.” Our authors prefer to call it “compulsory Zionism.”

The newcomers who arrived in Israel in the early 1990s went through difficulties similar to those encountered by every wave of immigrants. Finding work wasn’t easy, especially for the inordinately large number of physicians and musicians who turned up. The neurologist employed as a street cleaner was not merely a cliché but a reality. Housing, too, was a severe problem, even for those who could afford it. And those who were too old or infirm to work—a relatively high number of people—were a burden to the Israeli economy. Unique to this aliyah, or at least far more characteristic of it than its predecessors, were the problems resulting from the fact that many of its members—perhaps as many as thirty percent—were people who were eligible to enter Israel under the Law of Return but were not halakhically Jewish. The presence of hundreds of thousands of part-Jews or relatives of Jews led to endless friction with the Orthodox rabbis in charge of marriage, burials, and many other issues.

(Photo by Avi Ohayon, courtesy of the Government Press Office, Israel.)

In the course of time, most of the immigrants were more or less successfully absorbed, though a significant number of them, perhaps one hundred thousand, eventually left the country, returning, in many cases, to their land of origin. But this was by no means a unique phenomenon or a sign of failure. It had happened in all earlier immigration waves, even the Second Aliyah (1904-1914), which largely consisted of confirmed Zionists. It is, indeed, one of the few shortcomings of this book that the authors rarely refer to the experiences of earlier immigrants to Palestine and Israel, which were, in some respects, quite similar. They too initially encountered opposition, tended to maintain a social distance from other Israelis, complained about discrimination, and eventually established political parties to uphold their interests.

When I made the acquaintance of some of the more recent immigrants, I was struck by the great difference between them and the “refusenikim” who had left the Soviet Union in earlier decades. Like many of those who had fought for their right to emigrate, I had not been fully aware of how far this generation had moved from Jewish (let alone Zionist) traditions. This was in many ways a natural process, one that was also occurring in Jewish communities in Western Europe and America. Thus it was not surprising that upon their arrival in Israel they would keep to themselves, remain aloof from an Israeli culture they considered to be provincial, and continue to participate (through satellite TV, the Internet, and other means) in a Russian culture they believed to be superior.

I thought this pride in their specific identity was legitimate and on occasion touching, if sometimes a little idealized. Visiting Russian language bookshops in Israel, I encountered more of the popular Soviet novelist Valentin Pikul than Boris Pasternak, and more books by my late and rather dubious friend, Julian Semyonov, a writer of spy fiction, than the great poet Osip Mandelstam. I did see Russian translations of Leo Strauss and even of Emmanuel Levinas, but also a great deal of rubbish.

Still, there is no denying that the new immigrants are great readers and theatergoers, and they have added much to the cultural standing of Israel, perhaps most visibly in the worlds of chess and music. They have also established newspapers and television channels of their own (Arutz 9), founded an outstanding theater (Gesher), and starred in sports (especially track and field and gymnastics). They are overrepresented in the fighting units of the Israeli army and have played a very important role in the development of Israeli computer technology. It is difficult to think of a single field in which Russian immigrants have failed to make a significant contribution.

This is one side of the coin, and it is one that really shines, but there remain questions to which we still do not have satisfactory answers. The immigrants who came to Israel were the products of the Soviet system, however much they disliked and suffered from it. The culture and way of life they brought to Israel was the one they had absorbed at home and in school. In what ways is their Israel an extension of the old and new Russia, and to the degree that it is, does this constitute a problem? There are, after all, countries ranging from Canada to Switzerland in which different communities with different languages and cultures coexist; indeed this was what Herzl imagined the future Jewish state would look like. Nonetheless, some common cultural ground seems to be necessary to keep a society together and provide a minimum of national solidarity.

Consider, for instance, the case of Alexander Rosenbaum, who does not appear in the book. He is unknown outside the community of Russian speakers, but within it his name is one to conjure with. He was born in Leningrad and became one of the best-known and most popular bards. Now in his sixties, he is still going strong. Many millions love his “valse-Boston” and other songs, particularly those devoted to the criminal underworld—blatnoi. In Israel, Rosenbaum is something like an honorary member of Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beytenu; in the election campaign of 2009 he was invited to sing the party’s theme song. His “Yerushalayim” (readily accessible on YouTube) shows him walking the narrow streets of the Old City, invoking all the classic Zionist associations and symbols, including Palmach and Entebbe.

But Rosenbaum was also a member of the Russian parliament (the Duma), representing Putin’s party, and served as deputy head of the Duma’s cultural committee. Two years ago, his “Romance Kolchak” became a best-seller. Admiral Kolchak was an Arctic explorer, but he is better known as one of the heads of the White counterrevolutionary movement of 1918-1919. Kolchak was killed by the Bolsheviks after their victory. The song is devoted to Kolchak’s thoughts and feelings in the last minutes before his execution.

Jerusalem and Kolchak form a strange synthesis, if not exactly a shocking one: The admiral for all we know was no more of an anti-Semite than the current president of Russia, and it might even be possible, with a little effort, to find some common ground shared by Kolchak, Putin, and Lieberman. Galili and Bronfman do in fact devote a fair amount of time to drawing parallels between the latter two. Russian and Israeli patriotism, Kolchak, Putin, and Lieberman—what a fascinating combination, but how will it all add up in the end?

Commentators often seek to explain the politics of the Russian community in Israel in the light of its origins, neither the Soviet Union nor its successor having been an ideal preparatory school for a democracy. But there is another way in which the Russians’ past casts a shadow over them, as Shimon Peres astutely observed in an interview with Galili and Bronfman. In an attempt to account for the evolution of the immigrants’ politics in the 1990s, he observed that “they did not have any idea of what it was to be a small state. They thought that the Jordan was the Volga, not just a stream overrated for the sake of public relations. They are convinced that Israel acts out of weakness and not on the basis of a realistic understanding of its small dimensions.”

Russian Jews, like other denizens of the Soviet Union, had been cut off from the outside world. Their knowledge was limited to their home country, and it was this faulty perspective that probably shaped their world view and their thoughts on Israeli politics more than any other factor. Many of them have never quite understood that small countries cannot behave like superpowers without putting their survival at risk.

What is the future of this community? What will be the profile of the next generation, born in Israel, educated in local schools, and trained in the army? How will it impact Israeli society and culture and interact with other groups of olim such as the Ethiopians? Things have worked out well, as the authors note, in a small town like Netivot, on what Israelis call the “periphery” of the country, between Be’er Sheva and Gaza. But will the same happen elsewhere? They will certainly master the difficult language spoken in Israel, but how deep will their attachment to the country be? It would be interesting to learn more about “mixed marriages,” but such information is not yet available. The importance of the Russian language in Israel may well decline. The circulation of Vesti, the leading Russian-language daily, is now only a third of what it was in its not-very-distant heyday. But this is true for all the print media in Israel and, for that matter, in the world in general. The number of Russian-language bloggers in Israel is astronomical, but in many families the second generation knows hardly any Russian at all. In brief, the Russian-Jewish community, like much of Israel, is in flux. For now, at least, one ought to be grateful for Galili and Bronfman’s valuable report on the present state of affairs.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Spanish Charity

The sight of a secular Israeli artist in a cathedral confessional in Spain is one of the more interesting moments in recent Israeli fiction. A new novel by A.B. Yehoshua.

God’s Law in Human Hands

A Judean, a Stoic, a Jewish philosopher, a Jesus follower, and a rabbi walk into a seminar room at Yale, and Professor Christine Hayes asks them, “What do you mean when you say divine law?”

A Cedar of Lebanon

In addition to the weight survivors feel, Friedman bears the burden of giving voice to the place that shaped young men’s lives and took others, while leaving no official trace.

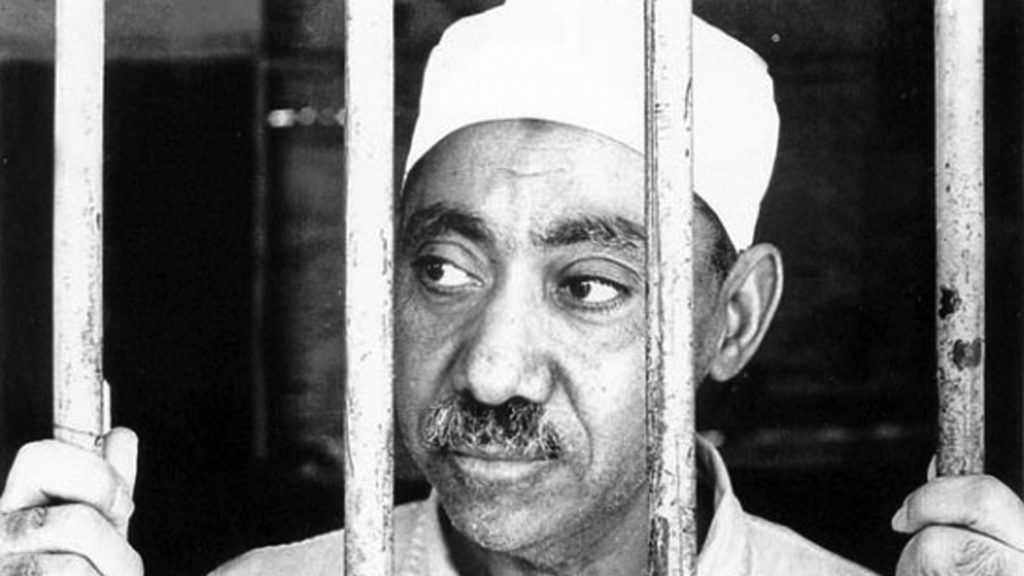

Qutb’s Milestones

A timely look at the intellectual father of radical Islam.

Martin Berman-Gorvine

As always, Mr. Laqueur's considerable erudition is very welcome. I fear that the phenomenon he points to--of Russian immigrants' bringing a "superpower" mentality to bear on the small country where they now live--might mesh all too well with a parallel Israeli tendency on both the Right and the (increasingly eclipsed) Left. I speak of the mindset that Israeli actions alone can determine the future of the country. On the Right, this means the idea that the settlers can behave however they want, in complete defiance of U.S. and world opinion; on the Left, this means a belief that a "land for peace" deal is the only thing holding back a utopian peace.