Cri de Coeur

Just 17 years old in 1938, the year he became famous, Herschel Grynszpan was barely over five feet tall and weighed only one hundred pounds. He was, we learn from Jonathan Kirsch’s detailed biography, a “habitual nail biter” who suffered from a lisp and a digestive problem that required a special diet. Perhaps because he was small and stood out in ways that would not have made him the most popular boy on the playground, he became a fighter who could hold his own, earning the nickname Maccabee (hammer) from his Jewish classmates.

It is natural that a scrawny, poverty-stricken Polish-Jewish boy living in the German city of Hanover as the Nazis began their campaign to make life unbearable for Jews would dream of doing something to measure up to his nickname. He certainly believed that he was acting to defend the Jewish people when he walked into the German embassy in France and fatally shot diplomat Ernst vom Rath. What is hard to believe, even after one has read Kirsch’s engrossing book, is that such a youngster would spend his final days as Joseph Goebbels’s poster boy for Jewish villainy, slated to be tried for his part in the Jewish conspiracy to embroil France in a war with Germany. Even more difficult to believe is the fact that this undersized adolescent was, long after his death, accused by Hannah Arendt of working for the Gestapo, tasked with “ridding Germany of an anti-Nazi diplomat and, at the same time, providing the Nazi regime with a pretext for a major escalation in the persecution of the Jews.” Arendt labeled him a “psychopath,” too, in Eichmann in Jerusalem while, Kirsch reports, one of Grynszpan’s defense attorneys when he was being held for trial in France called him “that absurd little Jew.” Even the Jews on whose behalf he claimed to act failed to see in him any sort of hero. The French-Jewish Alliance Israélite Universelle issued a statement that read in part, “We condemn the act of homicide which resulted in the loss of a German official.”

Vom Rath’s death served as the Nazis’ pretext for launching what they cynically called Kristallnacht, an atrocity planned months before that has all but eclipsed, but by no means buried, the memory of Herschel Grynszpan. Luckily for his biographer, however, both the French and the Nazis combed through every aspect of the boy’s life, going so far as to interview the director of his after-school daycare center. During his long incarceration (from 1939 until, the evidence would suggest, very late in the war), he was interviewed time and again by everyone from the French police to Adolf Eichmann. The result is a detailed map of the emotional and physical landscape of Grynszpan’s childhood and adolescence; his every movement in the days leading up to November 7, 1938, when he entered the German embassy in Paris and fired five shots at diplomat vom Rath, one of them fatal; and the aftermath of that act, both for him personally and for the Jews of Germany. Through his retelling, Kirsch wants most of all to reframe Herschel Grynszpan, to restore him to the historical record and place him beside Jewish resistance heroes such as Abba Kovner and Tuvia Bielski. It is an ambitious undertaking. Despite the evidence that vom Rath’s killing was merely a pretext for long-planned violence, Grynszpan is forever tied to the Kristallnacht pogrom that began November 9, hours after vom Rath’s death.

Herschel Grynszpan was born in 1921 in Hanover, ten years after his branch of a fractious, argumentative family left the small town of Radomsk, Poland. Before he was even a bar mitzvah boy, the Nazis had seized power in Germany, and his life began to change. “The life opportunities of the Jews have to be restricted,” as an internal Nazi report put it. “To them, Germany must become a country without a future, in which the old generation may die off with what still remains for it, but in which the young generation should find it impossible to live, so that the incentive to emigrate is constantly in force.” Properly incentivized, Herschel left in 1936 to live with his Uncle Abraham, a tailor in Paris. But he could not do so easily or legally.

He slipped across the Belgian border into France and moved in with his childless aunt and uncle. In Paris, he ran errands to earn pocket money, saw movies and hung out in cafés with other young Jewish refugees when his allowance held out or in the street when it did not, and religiously read newspapers that tracked the worsening situation in Europe. (One story that caught his attention was that of David Frankfurter, a Jewish medical student in Switzerland who, on February 4, 1936, assassinated a Nazi representative in Switzerland, one Wilhelm Gustloff.)

From time to time he acted on wild, improbable ideas: writing directly to President Roosevelt to ask for an entry visa to the United States and staging an impromptu hunger strike until his uncle gave him the 200 francs he needed for his utterly hopeless plan to join the French Foreign Legion. When Herschel was legally registered as a houseguest of Uncle Abraham with the Paris police, he applied for the papers he would need to stay in France: an identity card and a permis de séjour. In July 1938, his application was turned down.

This was a catastrophe. Kirsch spells it out in painful detail:

[T]he decision produced a formal decree of expulsion that was issued on August 11 and went into effect on August 15. The French Republic, in other words, afforded seventeen-year-old Herschel Grynszpan exactly four days in which to leave France. After August 15, he was subject to arrest and deportation if he remained in the country, but neither Germany, his country of birth, nor Poland, his country of citizenship, would allow him to enter because his German visa and his Polish passport had both expired.

His only choice was to hide. He found a refuge in a garret in his uncle’s apartment building, allowing his uncle to tell the police, when they came looking, that “his nephew from Hanover had moved out.” When his aunt and uncle moved to a new building, he stayed behind. In a neighborhood stuffed with refugees, Herschel was relatively free to resume his old life, dining with his Uncle Abraham and Aunt Chava and hanging out with his friends at their favorite café.

Back in Hanover, the rest of the family had it far worse. Even as they were subjected to more restrictions by the Nazis, their native land sought to disown them by stripping Poles who had lived outside the country for more than five years of their citizenship in October. A week after Herschel was ordered to leave France in August, the Germans announced they would cancel all residence permits to foreigners, issuing new ones only to people “considered worthy of the hospitality accorded them because of their personality and the reason for their stay.” A family of Ostjuden who had been on the public dole was unlikely to qualify for such “hospitality.” And despite pressure from Germany to do so, the Polish government insisted it would neither extend nor suspend its October deadline. In the kind of telling detail Kirsch weaves into his often complex narrative, we learn that as the Nazis planned the expulsion of Jews who had lived in the country for decades, ordinary Germans were playing a game called Juden Raus! (Jews Out!). The winner of the game was the “first to round up six Jews and hasten them ‘Auf nach Palästina!’” The problem, of course, was that in the real world, Palestine, like so many other places, would not take them.

With an efficiency the French lacked, the Nazis had drawn up a list of the 50,000 Polish Jews in Germany. Just days before Poland would no longer take them back, they arrested thousands, including Herschel’s parents, Zindel and Rivka, and his siblings, Mordecai and Esther. By their own ludicrously mendacious account, the Nazis treated these people humanely. They supplied all of the Jews “being made available to Poland” with alcohol, cigarettes, and food, including kosher meals for those who needed them. Solicitous SS men helped “as much as possible to carry their baggage, which was considerable.” The newspapers told a different story: The refugees were dumped off the trains without food or shelter in a no-man’s-land on the border and forced to march toward Poland by SS men shooting machine guns over their heads, even as the Polish border guards “brandished rifles with fixed bayonets” and fired warning shots of their own.

One week to the day after the Grynszpan family was taken from its Hanover apartment, Herschel received a postcard from his sister:

We were not told what it was all about, but we saw that everything was finished for us. Each of us had an extradition order pressed into his hand, and one had to leave Germany before the 29th. They didn’t permit us to return home anymore. I asked to be allowed to go home to get at least a few things. I went, accompanied by a Sipo [security policeman], and packed the necessary clothes in a suitcase. And that is all I saved. We don’t have a Pfennig.

After reading even more distressing reports in the Paris papers, Herschel demanded that his Uncle Abraham take the money that he believed his father had earlier sent for his benefit and forward it to his stranded family. His uncle refused, and in the fight that followed Herschel shifted between tears for his family and angry exchanges with his uncle before storming out. Although family and friends searched for him that night and the next day, they would not see him again until he was in police custody.

After spending a restless night in a hotel, he penned a postcard to his family. Begging for forgiveness from God and from them, he wrote, “My heart bleeds when I think of our tragedy and that of the 12,000 Jews. I have to protest in a way that the whole world hears my protest, and this I intend to do.” He never mailed it, nor did he remove the price tag from the small revolver he hastily bought at a gun shop. Everything this purported agent of some vast Jewish conspiracy would know about using a gun he learned from a brief exchange with the shop’s owner. When Herschel entered the German embassy, he walked past Count Johannes von Welczeck and talked his way into the office of the lowest-ranking legation official, Ernst vom Rath.

Herschel’s version of what happened in the office changed often in the years he was in custody. What is known is that he fired five shots from a few feet away, hitting vom Rath twice, then sat in an office chair without moving as embassy staff rushed into the room. Within a few minutes, he had been taken off the embassy grounds and handed over to the French police. After yelling “sales boches!” (dirty Krauts!) at the Germans, Herschel freely admitted what he had done and why. “I did it to avenge my parents who are miserable in Germany.”

Vom Rath, a young man from an aristocratic family who had joined the Nazi party a year before Hitler came to power, could claim membership in the elite club of those known as the Old Fighters, the Alter Kämpfer. Performing one last service to his Führer, he lingered for two days in a hospital bed before dying on November 9, the anniversary of the abortive Beer Hall Putsch, thereby providing the perfect festive occasion for the Nazis to perpetrate crimes that had evidently been planned well in advance of his shooting, right down to the list of approved Kristallnacht graffiti.

While the Nazis vilified him, Grynszpan’s Jewish brethren for the most part turned their backs on him. A leading Jewish newspaper in Paris even “published an open letter to Rath’s mother in which the editorialist ‘expressed great sorrow on the death of her son’ and implored her that ‘it was unjust to blame all Jews for her son’s death.’”

Grynszpan found himself supported publicly and financially by Dorothy Thompson, a leading American journalist who had been expelled from Germany in 1934 for her unflattering stories about the nascent Nazi Reich. Through radio broadcasts and writings, she told Grynszpan’s story, linking it to the larger persecution of Jews in Germany. Her fundraising efforts made it possible to hire a high-profile lawyer, Vincent de Moro-Giafferi, a French-Corsican who had seen only one of his death-penalty clients executed. Subjected to ugly abuse and threats by the German press immediately after he took the case, Moro-Giafferi was unfazed. He “officially warned the Germany embassy that, unfortunately, his people, not being as civilized as the Jews, believe in the blood feud, and that if anything happens to him he fears that there will not be one person dead in the Germany Embassy but they will be lucky if there is one alive.”

Moro-Giafferi also contrived a novel defense strategy, one unsupported by the evidence but which he felt had a better chance of succeeding than putting the Nazi party on trial. He concocted a story in which vom Rath had lured Herschel into a sexual relationship, either with money or with the promise of exit visas for his parents. Herschel wanted no part of this defense, and initially, it did not matter, as the French courts continued to push off a trial date and Herschel whiled away his time writing in his prison-issued diary, penning letters to friends and world figures (including Hitler), and meeting with lawyers and visitors. But outside, the world was changing. Germany and France were at war (if not yet fighting each other), and both the judge and some of Herschel’s lawyers went into army service. The process of forgetting Herschel Grynszpan that Kirsch seeks to undo had begun, as Grynszpan’s requests for a trial date were ignored by the courts and journalists turned to more compelling stories.

His disappearance soon became both physical as well as metaphorical. In the chaos that resulted from the Nazi invasion of France, Grynszpan’s jailer endeavored to evacuate him along with other prisoners to the unoccupied southern part of the country and, in the process, lost track of him. They might have done so permanently had he taken advantage of repeated opportunities to elude them, but he apparently found the prospect of being on his own worse than captivity. He was relieved to land in a prison in Toulouse, but not for long. If the rest of the world had forgotten him, the Nazis had not. Barely a month after the Germans entered Paris, Herschel was in a cell in Berlin.

From here, the record becomes both sketchy and untrustworthy. The Nazi mania for documentation was not matched by one for accuracy. We have it on the authority of Eichmann (who personally interrogated Grynszpan) that Herschel was never tortured or physically abused, if only because it would not look good if the defendant at the show trial the Nazis had planned was bruised and battered. A German political prisoner held in the same prison reports that the boy was fed meals from the guards’ canteen, rather than prisoners’ food, and worked as an orderly, rather than at hard labor.

But no show trial ever materialized. As Kirsch reports, a year after the Germans found Grynszpan he told a Gestapo agent a version of the story Moro-Giafferi had concocted—that he and vom Rath had a homosexual affair and that he had gone to his office to break it off. The details of his story would change under subsequent questioning, but he would not back away from the central premise. This, in Kirsch’s eyes, was an act of courage, a move to deny the Nazis the trial they so desperately wanted. Any testimony that “Rath was a sexual predator who preyed on Jewish boys” would constitute “not only an embarrassment to the Third Reich but a crime twice over under the Nuremberg Laws.”

Of course, what made Herschel Grynszpan change his story some three years after he committed the murder is a matter of conjecture, but if this indeed was his intention it would fit well with Kirsch’s overarching goal of finding the hero inside the troubled young man. If perhaps Kirsch takes his case too far, one cannot dispute that at a time when all too many sought coexistence with the Nazis, a 17-year-old faced them head on and took action. Speaking in a French court, he demanded dignity for his people. “It is not, after all, a crime to be Jewish. I am not a dog. I have the right to live. My people have a right to exist on this earth. And yet everywhere they are hunted down like animals,” he told the judge.

The Nazis did indeed hunt Herschel Grynszpan down, but he made himself useless to them. Conjecture and conspiracy theories swirl around his ultimate fate, some plausible (he was executed along with other high-value prisoners shortly before the war’s end), some fanciful (he returned to France and worked as a mechanic, hiding from relatives in shame over his homosexuality). We know only that there is no sign of him after the war’s end. Kirsch puts it most succinctly: “No official document of the Third Reich discloses his fate.”

Sizing up Grynszpan’s legacy, at the end of the book, Kirsch sees some significance in the fact that no street is named after him in Israel, where many roads and avenues bear the names of Jewish resistance fighters. He may be mistaken. A street named Grynszpan connects Yigal Allon and HaShomer in Rishon LeTzion. Another runs parallel to Derech Ze’ev Jabotinsky in Petah Tikva. But Kirsch is not wrong to point out that not only Grynszpan’s act but all resistance to the Nazis led to harsh collective punishment of innocent people. And he makes a compelling argument that to treat Herschel Grynszpan differently than other resistance figures, who knew that their actions would bring down retribution on others, is an injustice. Grynszpan may have been a flawed hero, but he fought back against the Nazis and died as a result.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Our Master, May He Live

Rashi's commentary on the Chumash isn't just about textual puzzles, it's about God's love for the Jewish people. So argues Avraham Grossman in a new biography.

Smitten with Sympathy

As the sea split, God shushed the angels, saying, “My handiwork is drowning in the sea and you are reciting songs before me?”

Pro-Creation

Economist Bryan Caplan thinks parents “overcharge” themselves when it comes to investing in their children. Glückel of Hameln knew better.

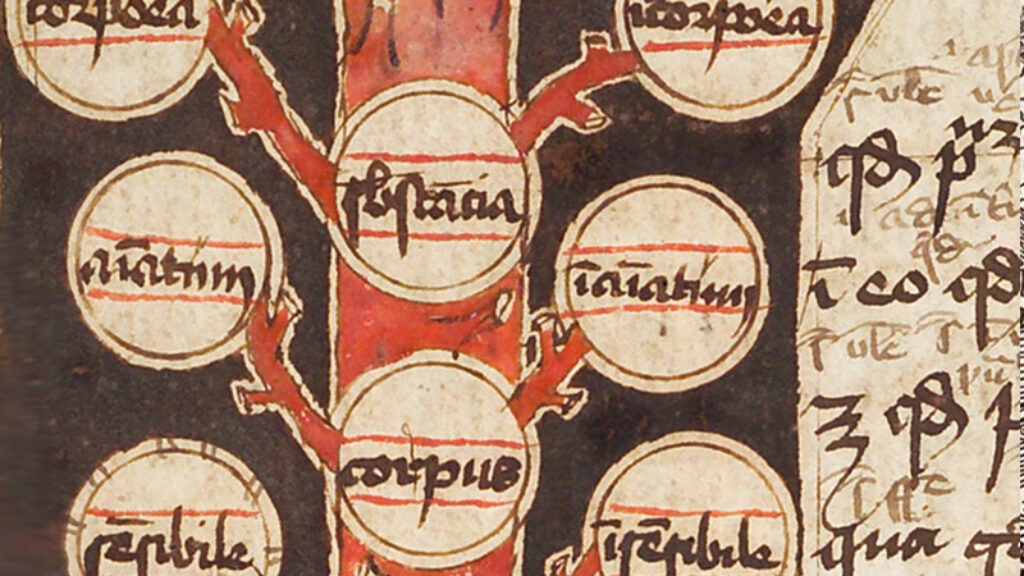

Roots in Heaven, Branches on Earth

Nothing sounds more idolatrous than drawing God. But that is just what a diverse bunch of medieval Jewish visionaries and scribblers set out to do.

Martin Berman-Gorvine

What a story. Herschel Grynszpan's memory deserves to be honored. And here is yet more evidence of the fraudulent basis of Hannah Arendt's moral authority.