The Man Who Thought in Pictures

I

n describing his friend S.Y. Agnon’s style of thinking, Gershom Scholem emphasized the extent to which he was “unable and unwilling to have a conversation about abstract ideas—rather only in stories or parables [meshalim].”

You’d start to speak to Agnon conceptually, and he’d immediately change the subject—‘Let me tell you a story, let me tell you a maiyseh.’ He thought in pictures. Agnon expressed everything, completely legitimately, as one who thinks in pictures.

This was a perceptive remark, so it is interesting that so few of Agnon’s stories have been illustrated. Perhaps the most significant illustrations have been those of Avigdor Arikha, for the sections of Only Yesterday published under the name Kelev Hutzot (Stray Dog), in which author and artist collaborated in the drawing of the demonic dog Balak. (The Agnon House held an exhibit of these engravings, sketches, and drawings in 2010, and a catalog was published in conjunction with the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.) Theodor Herzl Rome, who was the son-in-law of Agnon’s patron and publisher Salman Schocken, produced a number of spare, stylized line drawings for certain publications, which have been recycled in various printings of assorted stories both in Hebrew and in translation.

But only now, forty-three years after the Nobel laureate’s death, have Agnon’s stories been rendered into a comic book. Israeli illustrator and cartoonist Shay Charka has put pictures to words for three of Agnon’s stories that have special appeal for children.

One of Agnon’s best-known short stories, and likely the first that many school children encounter, is “Fable of the Goat,” the story of a magical cave tunnel between Exile and the Land of Israel, and a delightful but unfortunate goat who can lead the way through. Actually, this story was the first of Agnon’s ever to be illustrated. When it was published in 1925, very shortly after Agnon’s own return from his twelve-year sojourn in Germany, the story was simultaneously issued in two publications—for adults in the literary journal Hedim, and as part of a series of booklets for children illustrated by Betzalel artist Ze’ev Raban. The fact that the same story would be presented as both adult and children’s literature highlights the rich midrashic or aggadic nature of Agnon’s writing.

It’s precisely on this point—Agnon for children?—that Charka’s edition is so interesting. A very fine graphic artist and illustrator, Charka is best known for his series of “Baba” books illustrating talmudic aggadot and Biblical stories, as well as his satiric political cartoons. In this book we witness the degree to which illustrators are inevitably commentators. For example, Agnon doesn’t describe the cave passage between Galicia and the Galil through which the goat leads the boy, dispatching it in a mere three short sentences of half-rhyme. Like Lewis Carroll’s rabbit hole, C.S. Lewis’ wardrobe, or J.K. Rowling’s Platform 9¾, it’s merely the mechanism that transports the hero from our world into a more magical one. But Charka lavishes three pages (out of twelve) on the passage. Along the way we see graphic hints to every ram or goat in Jewish history, from the “ram caught in a thicket” at the binding of Isaac, to the Yom Kippur scapegoat, to the Chad Gadya of Seder night, and more.

In short, there’s a lot of Jewish history in the passage between the diaspora and the Holy Land. In this way Charka preserves some of the dual valences of Agnon’s text, which simultaneously aims at children and their parents. It also shows how Charka’s drawings are a kind of midrash on Agnon’s stories, which are of course themselves a modernist distillation of the language and lore of the Mishnah, Talmud, and midrashim, together with the medievalists and Hasidic masters.

The other well-known story in the collection, “From Foe to Friend,” tells of its narrator’s attempt to settle Jerusalem’s Talpiot suburb despite the opposition of the “King of the Winds” to blow his house down. Virtually every commentator on this story has pointed out that Agnon’s Talpiot rented home was plundered during the 1929 Arab Uprising, leading to the eventual construction in 1931 of his house (now a museum and study center). Following that interpretive line, Charka draws the narrator as a caricature of a young Agnon himslf, and the sturdy house built at story’s end is none other than Beit Agnon, though, somewhat oddly, more as it looks today after its extensive renovation in 2009. (There are also graphic references to Rav Kook and Bob Dylan.)

While the first two stories are well known and regularly taught in the Israeli schools, the third will be unfamiliar to all but the most diehard Agnon fans. In “The Architect and the Emperor,” Charka has taken one paragraph from Agnon’s late novel To This Day and illustrated it as a stand-alone story, which tells of an old, distinguished architect who is commanded by the king to construct a new castle: “Years went by and nothing was done, for the architect had lost all interest in working in wood and stone.” Instead, he takes a gigantic canvas and paints “a castle on it so skillfully that it looked real, and sent the emperor a message that the task was completed.” When the monarch discovers it’s nothing other than a two-dimensional painting, he screams in his fury, “Not only have you disobeyed my orders, you have deceived me into thinking that the mere appearance of a building is a building.” At that moment the architect (who is drawn to look like the elder Agnon, so familiar to us from the fifty shekel bill) knocks on the door of the painted palace, whereupon “the door opened and the architect stepped through it and was never seen again.”

Agnon’s little aggada can be read on at least two planes: We can understand the desire of any artist to escape into his own work. But artistic creation also becomes an actual embodiment of an abstract ideal. The architect’s palace, which exists only in blueprint, has a Platonic existence of its own. The fusion of word and image in graphic novels may have a special power to evoke this second meaning.

Significantly, Charka has resisted the temptation to modernize Agnon’s poetic and sometimes archaic Hebrew. Nor does he insert nekudim (Hebrew vowels) into the text, which is penned in his cartoonist’s hand. Although the characters are given occasional lines of dialogue in “thought balloons” which are original to Charka and not Agnon, the words and style are essentially Agnon’s. It’s pleasing to think that the audience for this book will read Agnon’s rabbinic Hebrew and not be put off. It also underlines the power of illustration: Readers will know that the archaic, mishnaic word meshicha means a rope because they’ll see the cord wrapped around the goat’s tail. One hopes that they will also catch the deliberate echo of the word mashiach (messiah) that Agnon intended.

Since Charka does occasionally alter Agnon’s texts, it would have been better had Schocken included the canonical versions of these stories in an appendix (without illustrations each is quite short, two pages would have done it). This would have made the volume an even more effective educational tool. Nonetheless, one hopes that this important and delightful partnership between author and illustrator will introduce Israeli children (and their parents), and Hebrew students in America, to the magic cave of Agnon’s prose.

Suggested Reading

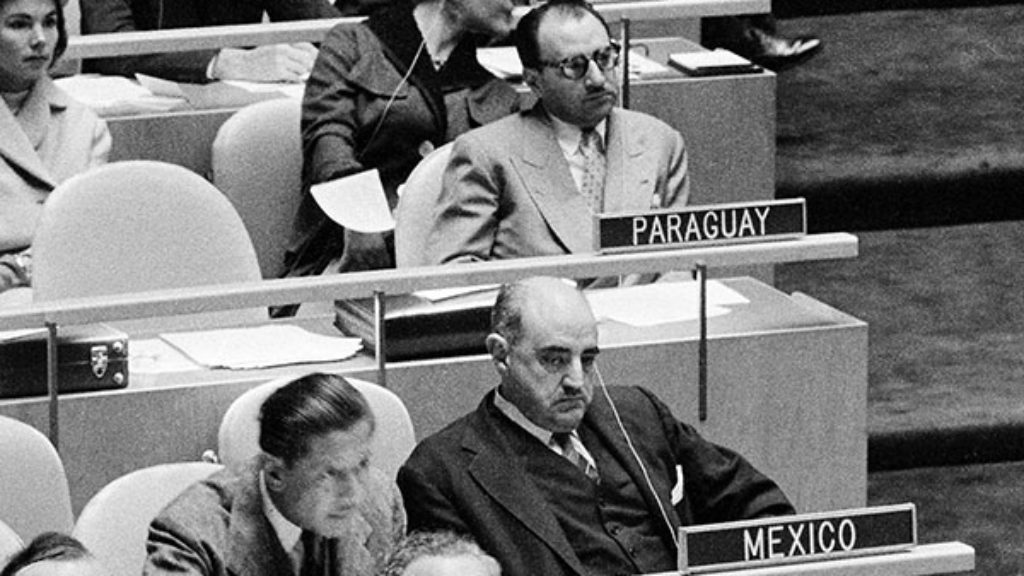

Universal Rights and the Particular Jew

Jews, like so many other minorities, whether they had states or not, deserve recognition and protection as nations. But these universal rights have eluded Jews, even as they worked to ensure them for others.

The Rise of Hank Greenberg

On Rosh Hashana, Greenberg went to shul, then the ballpark and hit two home runs. "Hank’s Homers are strictly Kosher," said the Detroit Free Press.

Rashi and the Crusader: A Legend

Did the great biblical and talmudic commentator meet Godfrey of Bouilon? A fascinating excerpt from Gedaliah ibn Yahya's Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah.

Overturned Tables

Despite his incontestable Jewishness, Jesus never participated in a Seder as the Mishnah describes it any more than he intended for Judeans to abandon biblical law for the worship of God’s only begotten son.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In