Universal Rights and the Particular Jew

In 1925, Jacob Robinson, a Jewish lawyer, former German prisoner of war, and member of Lithuania’s parliament, gave the keynote at the Congress of European National Minorities and put his finger on the fatal flaw of the League of Nations. It was, he said, “a league of states, and not a league of nations. Its members are only governments and not citizens.” Its model of reciprocity, he darkly quipped, was “I hit my Jews, you hit your Jews.”

In other words, Jews, like so many other minorities, whether they had states or not, deserved recognition and protection as nations. Whether, as America’s founders and France’s revolutionaries had asserted, all individuals were endowed with inalienable rights was moot. Only states could deliver basic rights, and without a Jewish state of some sort, there were no Jewish rights to be had. The idea that there could be a delivery system for rights other than a nation-state was made thinkable by the unthinkable trauma of statelessness visited on Jews and other “undesirables” over the next two decades.

Today, as authoritarianism and xenophobia surge, the global human rights apparatus meant to tame those evils has become a cruel joke whose running punchline is monomaniacal, wildly imbalanced criticism of Israel and regularly, by implication or worse, the Jews. Israel, for all its flaws, is nowhere near the depravity of dreadful regimes that escape United Nations’ censure. Is there something about human rights as an idea and institution that is inimical to Jews?

The question is sharpened when we recall that some key architects of the human rights movement, including Robinson, were not only Jewish, but active Jewish nationalists. James Loeffler, a historian at the University of Virginia, has now told their story. His book belongs on the shelf of anyone interested in human rights or modern Jewish political thought and history. He marshals remarkable archival research, literary grace, and philosophical insight to recover a forgotten chapter of history (several, actually) and make us think more deeply about political ethics, both Jewish and universal.

His genealogy of human rights shows the particular role that group rights, usually seen as an illiberal idea, have played in the history of modern liberalism. It also casts light on the deep theological undercurrents shaping the seemingly secular dispensation of human rights.

The book’s clever title plays on the epithet Stalin bestowed on Jewish intellectuals before murdering them. But Loeffler has a larger point: He indicts the contemporary “historical amnesia” that has yielded “a lazy dichotomy between nationhood and cosmopolitanism.” This, he argues, has left us “with a human rights universalism that pretends to come from nowhere and a Jewish nationalism that is positioned in opposition to the world.”

At the center of Loeffler’s story is a quintet: Jacob Robinson; Hersch Zvi Lauterpacht, a major figure of postwar international law; Peter Benenson, the founder of Amnesty International; Jacob Blaustein, the longtime president of the American Jewish Committee; and rabbi-activist Maurice Perlzweig. (The informed reader may ask: Where’s the father of the Genocide Convention, Raphael Lemkin? Good question, but hold that thought for now.)

The intertwined stories of these

five men bring together two discrete trends in recent historical scholarship,

one exploring how human rights movements and institutions arose so swiftly in

the mid-to-late 20th century, only to flounder soon

after; the other asking whether Zionism was the only form of modern Jewish

nationalism. Briefly, it wasn’t. “Autonomists,” most famously the great

historian Simon Dubnow, who were not so much anti-Zionist as un-Zionist, argued

that Jewish national identity was a brute social fact that could be

accommodated within nation-states which were committed to protecting the

rights of minorities. This was a proposition with which Zionists did not

necessarily disagree.

In 1919, the Zionist movement called not only for recognition of Palestine as the Jewish national home and equal rights for Jews in all countries but also for Jewish national autonomy—cultural, social, and political—in the countries where they would remain. The forum that was meant, in theory, to enforce those rights was the League of Nations. But the league’s dominant powers, France and England, weren’t interested. There emerged instead a system of minority treaties, giving Jews and other minorities freedoms and protections—as individuals, utterly dependent on the political will of member states.

The league was a political failure, but it was a legal failure, too. The death of its minority rights system only sharpened the question of how to square nation-state citizenship with national belonging beyond borders, a question whose most vivid symbols and actors were, then as now, the Jews. Hence the dark comedy of Jacob Robinson’s remark to the Congress of European National Minorities.

Robinson wasn’t the only Jewish jurist trying to think all this through. In 1927, Lemberg-born Hersch Zvi Lauterpacht, founder of the World Union of Jewish Students, published the doctoral thesis he had written at the London School of Economics. States’ territories, he said, are their properties, not the romantic inheritance of their peoples. Sovereign states in international society, like sovereign, property-holding individuals in liberal society, are, and must be, bound by laws—in the case of states, international laws. These ideas would guide him through a celebrated career as a professor at Cambridge and on the world stage.

Meanwhile, Maurice Perlzweig, Orthodox-born Reform rabbi, leading English Zionist, and head of the British section of the World Jewish Congress, worked through the late 1930s to remake the WJC from a quasi parliament into a self-defense agency. Jews, he said, had to claim “human and national rights” together. Those years also brought home to Jews the sheer terror of statelessness as never before.

As the magnitude of the Nazi catastrophe dawned, so did the understanding that securing Jewish existence in the postwar world would take new institutions and new ideas. With European Jewry murdered and Eastern Europe falling to the Soviets, the search for Jewish rights shifted to America and Palestine.

Jacob Blaustein, Maryland oilman and head of the patrician American Jewish Committee, then perhaps the premier American Jewish organization, saw Judaism as “an apolitical religious faith” and a partner in “an American Judeo-Christian vision of human rights (that) would tame the fires of Old World nationalism and advance international democracy at one fell swoop,” obviating the need for Zionism. In 1944, the AJC drafted a “Declaration of Human Rights,” signed by 1,300 distinguished citizens, Jewish and non-Jewish, and rabbis of all denominations, a stepping stone toward 1948’s epochal Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (Neither mentioned the Holocaust.) The AJC also commissioned a volume by Lauterpacht titled An International Bill of the Rights of Man. The failure of the toothless League of Nations, European democracy, and vague notions of natural moral law, Lauterpacht wrote, showed there was no substitute for “rules, voluntarily accepted or imposed by the existence of international society.”

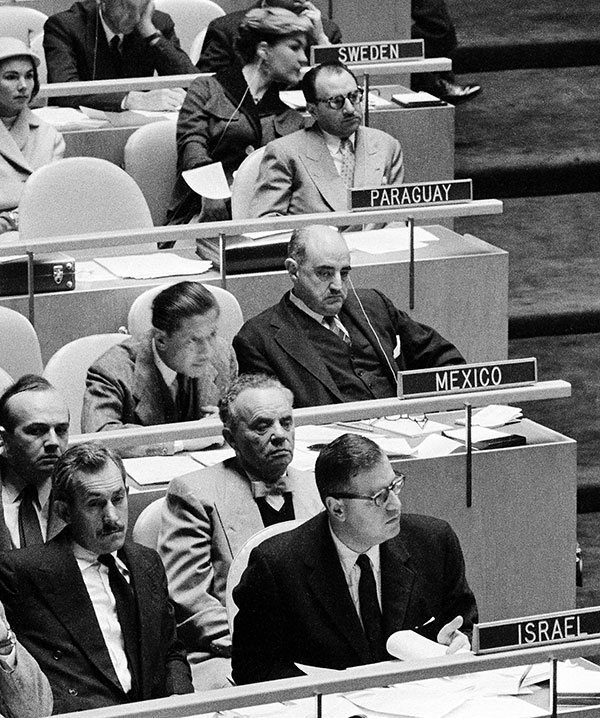

Robinson and Blaustein both disagreed with Lauterpacht’s internationalist vision. Both thought rights meant nothing unless backed by power. But whose? For Blaustein, it would be American power—for Robinson, Zionist. Neither gave up, though, on the promise of a new international legal order. Through 1945 and 1946, they and other Jewish rights defenders took part as best they could in the creation of the UN Charter, the war crimes trials at Nuremberg, and European peace treaties; each time they came back disappointed.

At the Nuremberg war crimes tribunals, Lauterpacht was on Britain’s prosecutorial team, and his idea of “crimes against humanity” was in the tribunal’s charter. Yet throughout the trials themselves, no one count in any indictment specifically mentioned the Nazis’ war on the Jews. Finally, in the fall of 1946, at the Paris Peace Conference convened to settle postwar arrangements, not one of the 21 participating countries would agree to introduce a memo on Jewish rights. Once again, the wages of Jewish statelessness had been made painfully clear.

The year 1948 is the great turning point of Loeffler’s narrative. On May 14, the State of Israel was declared. December 10 saw the passage of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and on December 11, UN General Assembly Resolution 194 brought Arab-Jewish hostilities to a (temporary) close. Crucially, the same Jews were engaged in all three and saw no contradiction between them.

By the logic of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, each and every individual stands vis-à-vis the state, their own or any other, as themselves a sovereign, at least when it comes to the individual rights articulated in the declaration. Unfortunately, Loeffler observes, left “out of this idealistic formulation was the crucial materiel that linked individual and state, and divided Arab from Jew: the nation.”

Yet the nation figured powerfully in an UN instrument enacted that same year on December 9, the day before the passage of the declaration. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was the brainchild of yet another Eastern European Jewish jurist, exile, and crusader, Raphael Lemkin. It was Lemkin who most clearly saw state-sponsored murder of nations qua nations, physical and cultural, as the distinctively modern crime. This complicated, fascinating figure scarcely figures in Loeffler’s book (though he will be the subject, one hears, of his next one). As Loeffler has shown elsewhere, Lemkin was himself a Zionist early in his career but later took pains to disavow it, along with his many other ties to Jewish organizations. This may seem paradoxical, since the very concept of genocide seems the most straightforward legal response to the murder of European Jewry. Loeffler suggests that it was precisely a desire to avoid the appearance of special pleading that led Lemkin, by then an American law professor, to obscure his Zionist past. What’s more, Lemkin had his doubts about the whole framework of human rights, which seemed too vague and declaratory to actually stop states from killing peoples and cultures. He kept his ideological and personal distance from Loeffler’s quintet, and they from him.

One suspects something else may have been at work, as well. Lemkin, too, had emerged from the legal circles committed to the group rights of national minorities. The one Jewish thinker Lemkin mentions in his carefully curated memoir is none other than the historian Simon Dubnow. In other words, while his peers were affirming both Jewish statehood and individual rights untethered from citizenship, Lemkin was working to transplant the prewar idea that minorities have group rights within other peoples’ states into international law.

Cambridge Law.)

Although he disagreed with Lemkin, Hersch Lauterpacht, who was one of the architects of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, still thought it was nonsense to declare rights before building the machinery to enforce them. He sent Ben-Gurion suggestions for Israel’s Declaration of Independence to this end. His formulations on the natural sovereign rights of Jews and civic equality for Arabs made it in, but his suggestions with regard to international law didn’t.

Jacob Robinson, who became a legal advisor to Israel’s delegation at the UN, believed in law too, but always in conjunction with politics. So he focused on state-to-state compacts: the genocide and refugee conventions, as well as the International Criminal Court (on which Lauterpacht served and which, in the absence of support from the Great Powers, went nowhere). Meanwhile, with Jewish nationalism relocated safely and exclusively to the Mediterranean, Jacob Blaustein became a supporter of Israel, a favorite of Harry Truman, and one of the only people allowed to call Ben-Gurion by his first name.

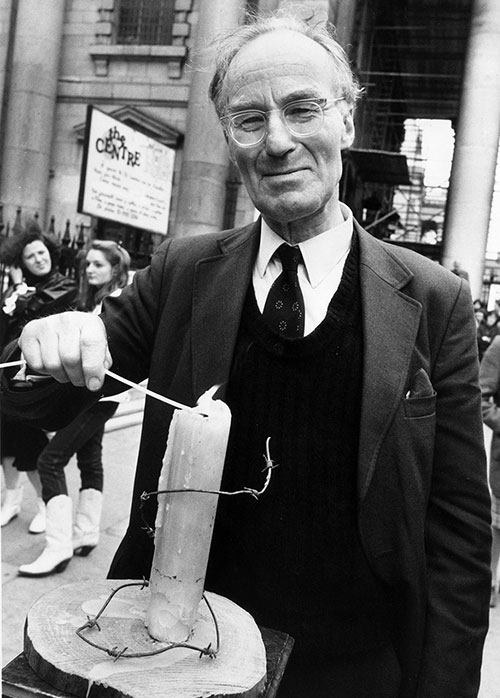

Peter Benenson (né Solomon) was born to a wealthy Zionist family. He was a student of Perlzweig who worked in the 1930s to bring Jewish refugees to England. During World War II, he served as a code breaker at Bletchley Park. After the war, he was a lawyer, journalist, human rights activist, and left-leaning Zionist. In 1958, he converted to Christianity, and in 1961 he founded Amnesty International. With Benenson’s story, the theological freight of Loeffler’s narrative moves to center stage.

Though Benenson had converted to Catholicism, he rejected the work of midcentury Catholic thinkers such as Jacques Maritain who had been instrumental in promoting the idea of human rights as an extension of classical ideas of natural law. Instead, Benenson drew from the deep well of Christian antinomianism first hewn by Saint Paul, who rejected the very idea of law as necessary for human salvation. “It has always seemed to me,” Benenson said in a characteristically Pauline remark, “that a humanitarian movement should decide its actions from the heart not from the book of law.”

Benenson himself didn’t disavow his Jewish roots. He sought and received the blessing of his former rabbi, Maurice Perlzweig, who was then helping to lay the groundwork for Vatican II and calling for “a new beginning” for human rights that would somehow rise above the hard political choices of the Cold War. True to Benenson’s thinking, Amnesty International focused not on groups but lone dissenters, “prisoners of conscience.” In doing so, it offered, as Loeffler astutely notes, a kind of antipolitics, pitting the individual against the state, with the individual helped by activists from abroad who “would also redeem themselves in the process.” Benenson and Amnesty International jettisoned the forums and chanceries of international law for the chambers of conscience and the court of public opinion.

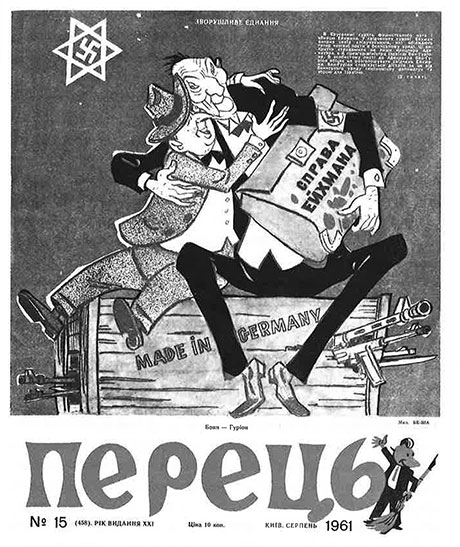

Meanwhile, the decolonization movement gathered steam under the sponsorship of the militantly antiliberal and avowedly anti-Semitic Soviet Union. Although awareness of the Holocaust grew through the 1960s, Loeffler notes its uniqueness, like that of the Jews, made for an ungainly fit with postcolonialism’s moralizing temper. To care about Jewish rights, as groups or individuals, was, at least on the radical Left, to paint oneself as an enemy of the oppressed of the earth.

In a decolonizing world increasingly focused on the evils of apartheid and colonialism, anti-Semitism hovered awkwardly between the categories of racism and religious intolerance. Like the Jews themselves, anti-Semitism was just too sui generis to fit the dictates of the human rights imagination.

Then came 1967 and the Six-Day War.

The 1970s saw both rising consciousness of human rights and the demonization of Israel as itself a quasi-colonial power. The unexpected resurrection of human rights was, as historian Samuel Moyn argued in his groundbreaking 2010 volume, The Last Utopia, a reach for ideals after the crushing disillusionments of Soviet totalitarianism, postcolonial authoritarian mayhem, the failed revolutions of the 1960s, and the floundering of international law. By mid-decade, the World Jewish Congress and American Jewish Committee’s UN offices were closed, the UN General Assembly had passed its infamous resolution equating Zionism with racism, and Amnesty International had won the Nobel Peace Prize.

That Amnesty International rose to acclaim as Israel took a beating was, as Loeffler notes and Marxists used to say, no accident:

The quest for the universal always begins with a rejection of the particular. . . . Amnesty International . . . took the form of a religion-less religion, or more properly, a secularized global Christianity. Human rights left behind international law to become a post-legal instrument to free the minds and bodies of the unjustly imprisoned and abused. . . . But to reach the universal, Amnesty had to leave behind the particular. In the post-1960s human rights imagination, the pole of stubborn particularism increasingly came to be symbolized by Zionism.

But history is full of surprises; in the late 1970s human rights activism and Jewish collective rights were reunited under the aegis of American power, as President Jimmy Carter made human rights the theoretical centerpiece of American foreign policy, while Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson made saving dissidents and Soviet Jews one of its primary objectives.

The Soviet Jewry movement united the seemingly antithetical rights claims of groups, states, and individuals. Its apotheosis came at the monumental rally for Soviet Jewry in Washington, D.C., in December 1987. That month also saw the outbreak of the First Intifada, and the relationship between Jewish politics and human rights activism has been tortured ever since.

Several truths peek out of the wreckage. First, although the drama of the particular and the universal runs through all humanity, in Jews and Judaism they are joined at the root. That is why Jews are, yesterday and today, the lightning rod for arguments over nationalism and globalism (and why Jewish thought holds such deep promise for the world). Second, liberal theories unmoored from traditional religion, local culture, or democratic politics quickly become vacuous and self-deceiving, ammunition for both hypocrites and tyrants. Nonetheless, the basic intuition underlying all human rights activism, that there are some things that governments must not be allowed to do to anyone, is one of the deepest lessons of Jewish history. It is as true for us today as it was to those emerging in 1919, and again in 1945, from the ruins.

Suggested Reading

The Ruined House (An Excerpt)

In 2014 Ruby Namdar won the prestigious Sapir Prize for his novel Ha-bayit asher necherav, the first time in the award’s history that it went to a writer not living in Israel. On November 7, 2017, Harper released it under the title The Ruined House: A Novel, in an English translation by Hillel Halkin. The Jewish Review of Books is pleased to present this excerpt from the novel’s opening.

Forging an Identity

How did a young Sephardi polyglot from Constantinople transform himself in Mexican society?

Revealer Revealed

Earlier this year, an email announcement of a publication made its rounds among scholars of Jewish studies. Written in the flowery Hebrew of the Eastern European Jewish Enlightenment, the advertisement proclaimed that the work would “reveal all secrets.”

Memory Palace

“Dust comes from something. It shows something has happened, shows what has been disturbed or changed in the world. It marks time,” Edmund de Waal writes to the long-dead Moïse de Camondo.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In