The Homecoming

I’m categorically anti the Americans in Vietnam,” British playwright Harold Pinter told the London Evening Standard in 1968. “And I feel strongly in favour of Israel.”

Up to that point, the work of Pinter—arguably the 20th century’s most important Jewish dramatist—had not been concerned with politics, much less Israel or Jewish issues. But he grew up in East London during the 1930s and 1940s, when anti-Semites and self-styled British fascists were a constant threat to bookish Jewish youths like Pinter. The experience left an indelible mark on him. He emerged in the late 1950s as part of the great wave of new British playwrights from working-class or Jewish backgrounds, a generation that included John Osborne and Arnold Wesker. “Angry young men” was the fashionable label the press gave them (though not all were angry, just irritable). Pinter’s groundbreaking early plays such as The Birthday Party and The Caretaker were uncanny blends of postwar European absurdist theater and traditional English drama. Audiences throughout the world were captivated by the bewitching rhythms and tones of Pinter’s dialogue, the savage wit followed by suggestive pauses and silences, bursts of violence, and moments of melancholy lyricism. His black comedies, whether about working-class eccentrics or upper-class mandarins, laced with menace and verbal fireworks, seemed to capture the precarious nature of modern life. Pinter’s influence can be seen in the plays of David Mamet and the films of Quentin Tarantino, wildly different as all three may be. In 1977, I saw an English-language production of Pinter’s 1965 masterpiece The Homecoming at the Jerusalem Theatre, with nearly the entire original cast reprising their roles. The production was played a bit broadly, perhaps a concession to the large hall and an audience filled with many for whom English was likely a second language. The actors milked Pinter’s dark humor for all it was worth, and the Israeli audience responded enthusiastically.

Yet the playwright himself had never visited Israel. Little wonder the excitement—at least among Pinter lovers—caused by an article in the Jerusalem Post a few months later reporting that Harold Pinter was visiting Israel to be present at the country’s 30th anniversary. At first blush, it would seem that the playwright and the Jewish state were worlds apart—Pinter’s world so indoors, Israel so outdoors—yet it was conceivable that a nation replete with territorial disputes, languages used as weapons, and narratives with no clear resolution just might be Pinter country, Middle East style.

The Jerusalem Post article was enticing but short on details. Pinter had just been to the Dead Sea (“hot!”) and Mount Masada (“high!”) and was planning to visit a cousin who lived on a kibbutz. And that was about the last anyone heard of Pinter’s visit.

Michael Billington’s comprehensive 1996 biography of Pinter doesn’t mention the trip—nor, it seems, has anyone else until now.

The 47-year-old Pinter’s companion on the journey, 45-year-old Lady Antonia Fraser (Dame Antonia since 2011), kept a diary. Fraser, a Catholic convert since her teens, along with her parents and siblings (the publication of Brideshead Revisited in 1945 had made Catholicism glamorous in England), grew up far from the mean streets of Pinter’s Hackney. The author of novels, detective fiction, and bestselling biographies of historical figures like Mary, Queen of Scots and Marie Antoinette, Fraser published a moving memoir of her relationship with Pinter, Must You Go?, in 2010. While cleaning out a cupboard in 2016, she came across the journal she’d kept during their 15-day visit to Israel in May 1978. Our Israeli Diary, unlike the memoir she wrote from memory, is a day-by-day account banged out on a portable typewriter every morning of their journey. It’s a vivid portrait of a famous couple in a place and time when everything seemed possible.

The British upper classes have always been diligent travelers and prolific travel writers, perhaps the result of having once possessed an empire. Fraser prepared for the Israel trip by reading Saul Bellow’s To Jerusalem and Back, while Pinter bought large sunglasses and sturdy shoes. “I think we both believe we will tramp through a great deal of history,” Fraser writes, an enticing prospect for a professional historian. At Heathrow Airport, Pinter observes that the other countries have “shared gateways” but Israel has only one, and the suggestion of the world’s continued hostility to the Jewish state is obvious. The flight’s two-hour delay doesn’t put Pinter in a good mood, and Fraser worries that the presence of fellow passenger Joseph “Teddy” Sieff, a well-known British businessman and Zionist, might provide a tempting target for terrorists seeking to blow up a plane carrying a prominent Jew; it doesn’t occur to her that Pinter himself is the most prominent Jewish passenger. Fraser might have considered Sieff a good omen, since he was the only person known to survive an assassination attempt by Carlos the Jackal when the famed terrorist shot Sieff in his bath on behalf of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine; the bullet bounced off the ridge of Sieff’s nose, and Carlos fled.

Ordinary tourists to Israel stay at ordinary hotels; Pinter and Fraser were guests of Jerusalem. Upon awakening on her first morning in the prestigious Jerusalem artists’ and writers’ center Mishkenot Sha’ananim, Fraser’s impressions are aptly novelistic and historical:

Brilliant hard sunshine one senses from an early hour outside the silvery white blind over the arched windows, and the traffic roars on the big road beneath Mishkenot. I peek up at a castle wall which I now realize is where the Jordanian guns perched before ’67 threatening the poor (literally) Jews in the Mishkenot area. I visualize wretched black-clad figures scuttling about, reconciling themselves to the fact that every now and then an arbitrary gun will blow them out of this world. But scuttling in the same place every day all the same.

In keeping with this ominous tone, the first thing they see in the Arab Quarter is a Star of David over a prison and an Israeli soldier with a large gun atop the roof of a building, prompting Pinter to remark, “A family face in the crowd.” Fraser is more sympathetic to Israel’s security concerns, noting that, “The world has decided that really unique among states, Israel must be a moral state . . . something no other state is expected to be!” She notes that Pinter is unmoved by the Western Wall: “He definitely felt no atavistic twinge.” Not surprising, since two years after his bar mitzvah Pinter had shocked his parents by renouncing Judaism. After his success, Pinter dutifully paid to send his deeply Zionist father and mother on trips to Israel twice before visiting the country himself.

In fact, Pinter actually feared visiting Israel, though not because of terrorism. He confesses to Fraser that he was afraid to go there simply because he might dislike both the nation and its people. The Israelis were not entirely sure what to make of Pinter and Fraser, either. As she frequently does throughout the diary, Fraser presents events as if they were scenes in a play, as in this exchange after a concert at the Jerusalem Theatre:

A woman describing herself as the Mme. Furtseveya of Israel, i.e. Arts Minister: “I know your name. Tell me why?”

Me, pausing and stumbling: “Well, I’m a writer, sort of a biographer.”

She is not very satisfied.

H., sotto voce: “You should have said, ‘Well, I left my husband for Harold Pinter and there was all this scandal in the newspapers.’”

There is naturally much sightseeing to attend to, including the obligatory trip to the Dead Sea, where Lady Antonia, like so many before her, is amazed that she can float on top of the salty, mineral-rich water. But both she and Pinter, pink-skinned Brits, are duly debilitated by the intense heat of the Israeli sun. Ultimately, Fraser admits they can take “only so much” of Israel and often retreat into their rooms to read British novels or share a copy of O Jerusalem!, a popular history of Israel’s War of Independence. Pinter also heartily partakes of Israel’s supply of beer, wine, and Scotch at the King David and American Colony hotels, each offering him much-prized quiet and solitude in nondrinking 1978 Jerusalem. By Saturday, the evening before Independence Day, Fraser reports that, “H. says he is very happy to be in Israel, adding, ‘What I mean is, I see no reason why we shouldn’t come here again. Here to Israel.’”

Both were enchanted by Israel’s people and landscape, though, unsurprisingly, they see the Holy Land through quintessentially British lenses. The owner of the American Colony Hotel is “a real Graham Greene character,” and a church in the Old City reminds her of Blackfriars at Oxford. While driving to the northern Galilee, she is simultaneously in awe of the country and reminded of her native England:

[W]e do see for ourselves for the first time exactly what the extraordinary achievement of the mad, and I mean mad, Israelis has been. For it must have been madness to come as they have come to a country without water, shade or even soil and there is this arid desert contained, don’t forget, by hostile Arab mountains (from which shells emerge in the air, terrorists by night) and yet insist on growing the green vegetables and flowers of Hertfordshire and Worcestershire.

Fraser is clearly in a long line of English Christian Zionists and philo-Semites, going back at least to George Eliot.

Still, nothing in England could prepare them for Masada, the ancient fortress atop a mountain plateau where 960 Jewish men and women held off a Roman legion of 9,000 for nearly two years before committing mass suicide in 74 C.E. to avoid subjugation. Ascending the rocky mesa in a cable car, they’re annoyed by tourists wearing, Fraser writes, “tiny hats, too tiny for their big heads with ISRAEL on them . . . And [with] loud voices which make Harold flinch.” But the historian in Fraser is moved by “the sight of the Roman rampart which creeps up behind the rock . . . How ghastly to watch that thing inexorably creeping toward you.” Meanwhile, the man whose plays inspired anxiety in so many audiences is suffering from a serious fear of his own—vertigo. It causes Pinter to “stagger slightly, turn white and half fall, half sit down . . . It is a terrible moment.” Fortunately, Lady Antonia takes Pinter’s hand in a firm grip and gently walks him down to the cable car, whence they return to ground level safely. Once again, Fraser captures the quality of their relationship in dialogue:

H. later: “You know I told you I didn’t know what the next stage of vertigo was. Well now I know. Coldness. Nausea.”

Me: “You were a hero—you got down!”

H.: “With your hand.”

He gives me a copy of Yadin’s splendid Masada inscribed “To Antonia, the girl who got me down alive.”

Later that night they discuss the history of Masada with British playwright David Mercer, married to an Israeli and living half of each year in Israel. Mercer disagrees with Eleazar’s speech to the Jews about the virtues of a chosen death, saying, “With my ex-Communist background, I have a horror of people impelled to do things en masse by the power of rhetoric.” But Fraser suspects that Pinter is “sympathetic to the Zealots, who preferred death at their own hands to slavery and subjugation, and death at the hands of the Romans.” Even a casual reader of Pinter’s plays, which show fierce commitment to freedom from coercion, would have to agree with Fraser’s assessment.

The couple had access to some of the best and brightest in Israel during their trip, and the diary name-drops luminaries such as Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek, former (and future) prime minister Shimon Peres, a host of Israeli actors, directors, and writers, and even a visiting Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. But an encounter with more personal significance for Pinter is when he and Fraser arrive, unannounced, like Teddy and his (non-Jewish) wife, Ruth, in The Homecoming, to visit his older cousin at Kibbutz Kfar Hanassi. Moshe Ben Haim, born Morrie Tober, grew up with Pinter in Hackney; Moshe came to Israel after fighting in the British Army in the Second World War and helped found the kibbutz in 1948. The cousins hadn’t seen one another in 30 years. Now a gray-haired patriarch, Moshe regrets that Pinter has come to Israel “now when we have a Fascist government” and proceeds to set forth the kibbutz principle to his famous cousin: “The man who negotiates a million pound deal for a kibbutz factory and the man who cleans the basin earn the same amount,” adding, “And they are content to do so.” This lesson in equality is interrupted by Sophie, Moshe’s sister-in-law, herself visiting from the Bronx, where she asserts that, “Everything the kibbutz has, the Bronx has and better.” The dialogue threatens to become a scene from a Neil Simon play until Moshe points out that the kibbutz was continually shelled from Syria during its first 19 years, and again we are in Pinter’s domain, where danger is never far away. Yet the photograph of Moshe and his son with Pinter, one of many color snapshots in the book, suggests an ease and happiness not often found in Pinter’s plays. With his open-necked shirt and tousled hair, Pinter looks like a kibbutznik himself.

From the modest environs of the kibbutz to the exalted halls of the Knesset. Observing the proceedings from a bulletproof glass partition above the Israeli parliament floor, Fraser is astonished to see an Arab communist legislator, who, moreover, had congratulated Sadat during the Yom Kippur War. She approvingly notes Paul Johnson’s observation that Israel is the only democratic assembly in the Middle East. Did Pinter agree? The diary forthrightly wrestles with the political issues that invariably crop up in every conversation about Israel, a country where, as Jerusalem Post military correspondent Hirsh Goodman tells Fraser, “you imbibe argument and even decisions of conscience every day just as you clean your teeth.”

Before coming to Israel, Fraser reports, Pinter was “obsessed with Begin” and “read out his speeches from time to time in tones of angry horror.” (Readers familiar with Pinter’s deep, theater-trained voice can easily imagine the effect.) The playwright worried about the new prime minister’s impact on Israel’s image among a rising generation that saw Palestinian refugees—not Jewish survivors of the Holocaust—as the true victims. Yet Fraser remains more sympathetic to the security concerns of Israelis. She has doubts about a Palestine set up so close to “the busy burgeoning Jerusalem” and wonders, “How can anyone expect the Israelis to welcome a state set up by Arafat and his murderous boys here?” She quotes Begin: “Why do they call me a terrorist . . . and Arafat a guerrilla?” and adds that Begin’s remark “strikes home.”

During a dinner hosted by an American couple who, Fraser suspects, will not settle permanently in Israel (“They’re such a Cambridge, Mass., young couple!”), Pinter and Fraser encounter longtime New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis. Lewis frankly loathes Begin and says, “The Israelis are so irritating! They are so wonderful, but they’re so irritating that they can’t understand how others see them. They won’t even listen.” By way of return, Pinter finds Lewis highly irritating, partly because of his insufferable pose as “an expert,” a pretension Pinter always disliked and regularly mocked in his plays.

But there is more to Israel than politics—more even than Jews and Arabs. Curious about everything, Fraser visits the Armenian Quarter of the Old City to view a collection of late medieval manuscripts. Her driver offers her still another aspect of Israel:

I was fetched in a large car with an Armenian chauffeur—all the Armenians I have met have been large and handsome and almost brigand-like except for their civilized clothes. The chauffeur was no exception. In the car a smaller dark man with a check shirt.

Me (the usual question): “Where were you born?”

Mr. Hintillian: “Here in Jerusalem.”

Me: “Then you have seen many changes in your lifetime.”

Mr. H: “In the Armenian Quarter we do not see changes.”

On the penultimate day of the trip, Fraser succinctly notes: “Sunday. ‘Shabbat,’ murmurs H. somewhat inaccurately, and makes my breakfast as he does at home.” Pinter may not have been the most devout Jew, but he was obviously a devoted boyfriend. For her part, Fraser spends the day shopping in Old City markets, having finally learned how to successfully haggle. She buys an ashtray for Pinter’s mother, “hoping vaguely that the design is neither Islamic nor Catholic.” They conclude their whirlwind journey on the Mishkenot patio, gazing at the walls of the Old City:

[W]e sit outside on a perfect evening as a full moon is gradually defined in the sky, and the shimmering sea-like effect of the desert beyond is lost. In the end the moon is very strong indeed. But the walls do not lose their own strength . . . For I do feel that these clean bright old walls are looking at me and have done so for two weeks.

In the end, Pinter decides that, despite his earlier fears, he likes Israel—the nation and the people. No doubt the sunny and outgoing Lady Antonia helped draw out the deeply private, often moody Pinter. Like her, he was impressed by the serious level of Israeli conversation (though admittedly he tended to socialize with secular, liberal Jews like himself). He confesses to Fraser that for the first time he really did feel Jewish—and that having her with him in Israel meant a great deal to him. At the airport, during the obligatory interrogation, the Israeli security officer asks them about their relationship to one another. “We’re lovers!” Pinter exclaims.

Suggested Reading

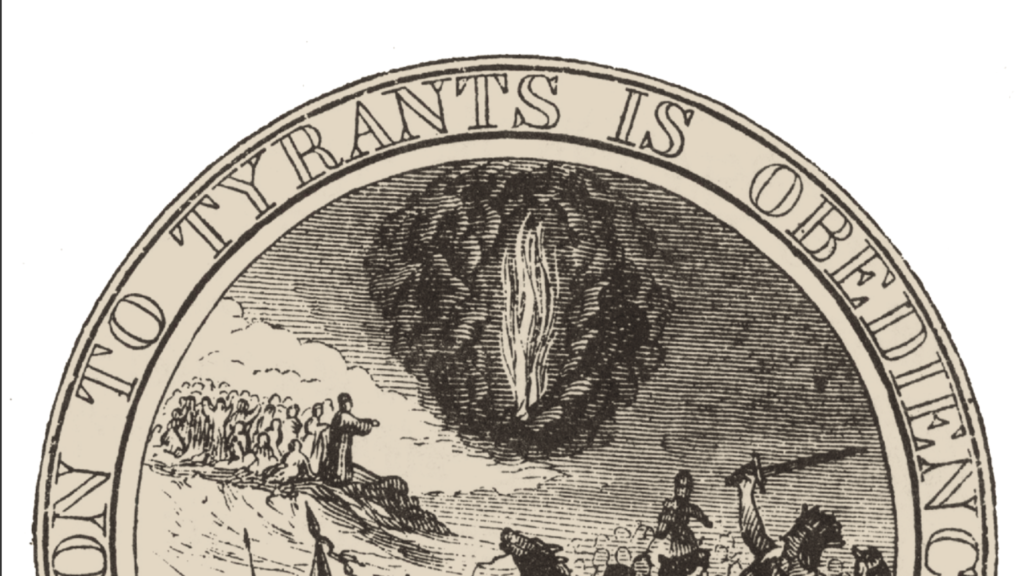

Leviticus on the Fourth of July

Biblical narratives and imagery have played a surprisingly large, even outsized, role in the formation of the American national consciousness and institutions.

Reorientation

A sober look at Jews and Christians under medieval Islamic rule.

My Father, Milton Himmelfarb

Personal reflections on the legacy of a sui generis Jewish American sociographer and essayist.

Unspun

I reserve the right to chat with you about all of my reading, whether there be dragons or not.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In