Doron Rabinovici and the Crisis of European Jewish Identity

Doron Rabinovici’s The Search for M opens on an interior of a Viennese coffee house, where the chairs are covered in green artificial leather and the lampshades in perforated metal. “One of the glass facades looked out onto a magnificent boulevard of the former royal capital,” the narrator notes. “The other faced a square and a monument to a world-famous anti-Semite.” Such is Vienna.

Rabinovici—novelist and essayist, playwright and activist—can sometimes be caught in a coffee house not unlike the one he describes here—one where, if the linoleum floors and worn crimson seat covers are anything to go by, time stopped, to borrow a line from Philip Larkin, “between the end of the ‘Chatterley’ ban and the Beatles’ first LP.” More than something transactional, Viennese coffee houses are the city’s living rooms: places to, as the great Austrian writer of the postwar period Thomas Bernhard once said, take one’s mind off of things and soothe one’s nerves.

At Rabinovici’s coffee house of choice, where we met one afternoon, sheltered beneath a canopy from the blazing summer sun, there is no statue of Karl Lueger—the former mayor of Vienna, whose anti-Semitism in part inspired Theodor Herzl to write The Jewish State—looming large. But those ghosts of Austria’s past and of Jewish history are central to his novels, as well as his essays and political commentaries, plays, and historical studies.

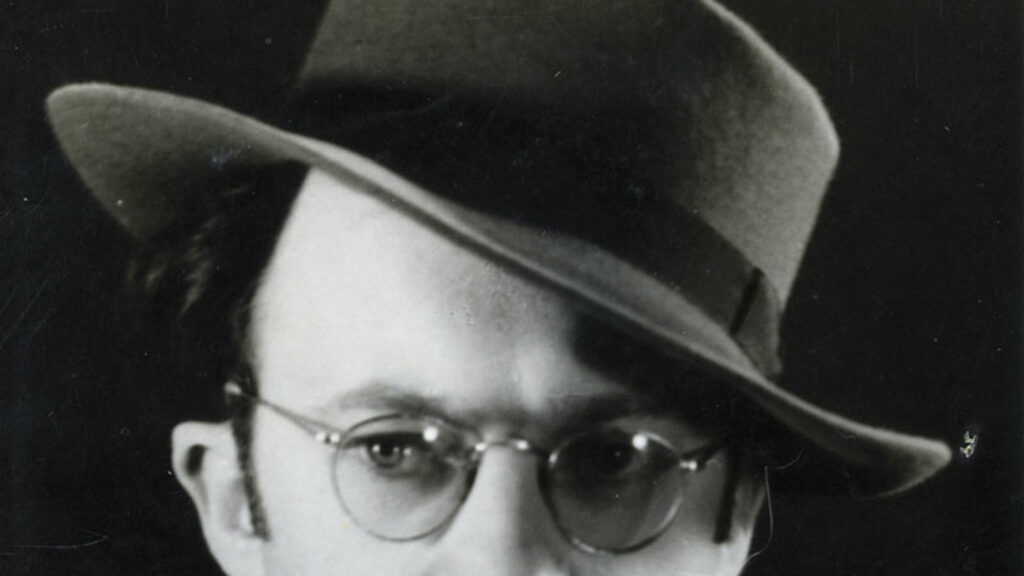

Born in Tel Aviv in 1961, Rabinovici moved with his family to Vienna in 1964. He has come to occupy a position in Austria akin to that of Amos Oz and David Grossman in Israel, in the sense that he writes and acts with two pens. In 1986, he was involved in the protest movement against Kurt Waldheim. Then a presidential candidate, the former UN secretary-general was found to have lied about his military service during the Second World War. The election campaign called attention to Austria’s failure to come to terms with its Nazi past and reawakened latent anti-Semitic feelings in Austrian society. Beginning in the mid-1990s, Rabinovici became further engaged in the national debate as a public intellectual, speaking and writing against the Far Right as well as xenophobic and anti-Semitic tendencies in Austrian society.

Following the election of 1999, after which the far-right Freedom Party under the leadership of the outlandish provocateur Jörg Haider entered into government with the center-right People’s Party, Rabinovici helped organize mass demonstrations against racism and political extremism. The most famous of these took place on February 19, 2000, and brought 250,000 opponents of the coalition onto the streets. In his speech that day, Rabinovici warned that having the Far Right as a governing party represented an existential threat to Austrian democracy and thus necessitated mass demonstrations as a form of resistance.

“Eighteen years ago, I was against Haider. We had great demonstrations and we really knew how to organize them,” Rabinovici recounted to me. Relaxing outside, having just filmed a spot for a German nightly news program, we chatted as he enjoyed a bowl of beef soup with semolina dumplings, followed by a salad of halloumi and arugula with balsamic vinaigrette. “We played our hand as well as we could and I knew how to give a speech. Today, I can say that some of those speeches were successful.” In spite of current political conditions in Austria, he is not ready to jump back into the fray in the same way, “not because I think [rallies] shouldn’t be done but because I think others can do them better. I’d deliver a speech if they wanted me to, but today I’m more interested in fiction as I think it has a greater effect in the long run.”

Rabinovici’s first collection of short stories, Papirnik, was published in 1994, around the time he became more involved in public debate. From those earliest stories through to his novels such as The Search for M and Elsewhere, Rabinovici has been concerned with questions of identity that come with living as a Jew in postwar Vienna. In contrast to his polemical writing, Rabinovici’s novels are riddled with doubt and confusion, anxiety, uncertainty, and contradiction, and speak in a multitude of voices as opposed to just one.

“If you live in Vienna as a Jew, you are confronted” every day with these questions of identity, Rabinovici told me. “The moment you say your name, Doron Rabinovici”—pronounced as Rabinovitch—“you immediately become an expert on Middle East politics, National Socialism, religion, anti-Semitism, and racism.” To live in Vienna as a Jew is also to be reminded that those who perpetrated the Shoah were defeated yet, unlike the victims, were able to resume their lives afterwards.

“In this Catholic country everyone owed each other absolution just as long as the other in the particular case didn’t confess anything,” Rabinovici writes in The Search for M, a novel shaped by the conflicted and ambivalent feelings of the Holocaust survivors who returned to Vienna after the war and their children. The Search for M’s characters are defined by their insecure and unmoored identities, traumatized as much by the present as the past—by that which is left unspoken; the “omissions, the individual words, the shorthand code, the pauses, and the grim silence.” This unexpressed, silent past is a specter, roaming the novel’s terrain.

In particular, The Search for M depicts the experiences of second-generation Holocaust survivors—a subject which, until the novel’s publication, had not been widely discussed in Austria. The parents saw “the return of their murdered relatives” in their children and though they wished for them to be unburdened by the past, this was impossible. Dani Morgenthau is warned of “the need to always eat copious amounts of food and to pay attention to outward appearance since it could come in useful in a time of need.” Arieh Arthur Bein is told that “nobody who hits you gets off unpunished” but is never quite told why:

When Arieh said: “I don’t know anything about you, father, not who you are or who you were,” Jakob Fandler laughed.

“Who I was will be on my gravestone. Have a little patience, son.”

The fears and anxieties of the second generation, inherited from the first, manifest themselves in Dani and Arieh to the point of exaggeration and even caricature. Incapable of rebelling against his parents—“to protest against them meant to abandon them”—and consumed to such an extent by the pains of the past that he breaks out in rashes and hives, Dani becomes someone who assumes the guilt of others in order to relieve that burden. Arieh seeks to avenge the past by joining the Israeli secret service in the role of an assassin. “Just like your father,” Arieh is warned, “you act as if you were living underground and hiding from extermination.” What unites both characters is a search for the guilty in, as Rabinovici writes, “the native land of Lueger and Schönerer, Hitler and Eichmann.” They are, in a certain sense, looking for themselves in other people’s crimes.

The latter half of the novel is consumed by the titular search for M: the phantom figure Mullemann—who, it transpires, is Dani. Bound up in bandages and rags, he walks the streets of Vienna at night, confessing to offences he did not commit. Haunting the Jewish community, Mullemann functions as a totem, an anti-talisman, both representing and taking on all their anxieties. “We wanted to buy our freedom from our guilty feelings toward the victims and transfer all the debts to your accounts,” Arieh is told during the search for Mullemann. “It may be that you’ve been forced to live with the legacy of our burden of guilt.” Mullemann, then, is a manifestation of the second generation—those born with numbers on their arms; “invisible, but it’s tattooed into us under our skin”—but a product of the first. Mysterious and surreal, The Search for M is a novel pieced together out of narrative fragments and glimpses into the lives of others, which feels more intelligent than the reader and where one is constantly on the hunt for clues and hidden meanings in order to navigate safe passage to the book’s conclusion.

Elsewhere is an altogether different novel structurally, albeit one that plays with similar themes. (Its clear, smooth translation by Tess Lewis is good enough to make one wish she had been responsible for the English edition of The Search for M, too.) Ethan Rosen is a citizen of nowhere, living the transient, shuffling life of a professor and researcher, whose demands often find him engaged in transcontinental travel to and from academic conferences. Reading the newspaper on a flight home from Tel Aviv to Vienna (somewhat like Rabinovici, Ethan is born in Israel though now lives in Austria), he finds himself incensed by an op-ed written by his rival, Rudi Klausinger, and attacks him in his reply as an anti-Semite.

This turns out to be a big mistake, one which precipitates identity crises for both Ethan and Rudi, for Rudi had quoted extensively from an earlier article written by Ethan himself, whose words he did not recognize as his own. His father’s failing health grants Ethan an excuse to flee embarrassment and rancor in Vienna for Tel Aviv, but as someone who often finds himself neither here nor there and whose exact parentage later in the novel is called into question, Ethan finds that these questions of identity and home cannot be escaped so easily. Rosen is an exile everywhere, constantly longing for a home. “In Tel Aviv, you give talks on those Muslim ruins,” his mother chides, while “you lecture Austrians about anti-Semitism.” Ethan has a visceral reaction to religious Jews in Israel but would defend them wholeheartedly were he in Austria, one character observes. He is, at least in part, Israeli and drops everything to return to Israel upon news of his father’s ill health but soon finds that all the gripes and quibbles that persuaded him to live elsewhere in the first place resurface.

There is in a sense not one but many Ethan Rosens. He (or they) experience(s) life as a mélange of languages and arguments, talking, thinking, and acting differently whether in Israel, Austria, or the United States, so when he reads his own words staring back at him in the pages of an Austrian newspaper while sitting on a flight from Tel Aviv, he doesn’t recognize them as his own. When Rudi proclaims at novel’s end, over the grave of Ethan’s (supposed) father, that, “His Jerusalem was always elsewhere and everywhere at once. He was at home in interval spaces, where one human being meets another,” he might very well have been talking about Ethan himself.

When I spoke with Rabinovici, he told me, “You can live in Hebron and the majority of Jews would ask you, ‘You’re a lunatic, how can you live here?’ You can live in Vienna and a majority of Jews would ask, ‘How can you live here?’ You can live in New York and some Zionist will ask you, ‘How can you live here?’ And you can live in Israel and someone will ask, ‘How can you stand this place?’” Behind this question, Rabinovici sees another: “How can you live on this Earth after what has happened to us?”

Suggested Reading

When Heidi Met Shimen

Whereas Heidi and her woke progeny scatter in the winds of the American landscape and the heirs of Yitzy and Ben find themselves growing further apart, their Israeli counterparts find themselves socializing together, mostly serving in the army together, and sharing a Jewish cultural vocabulary.

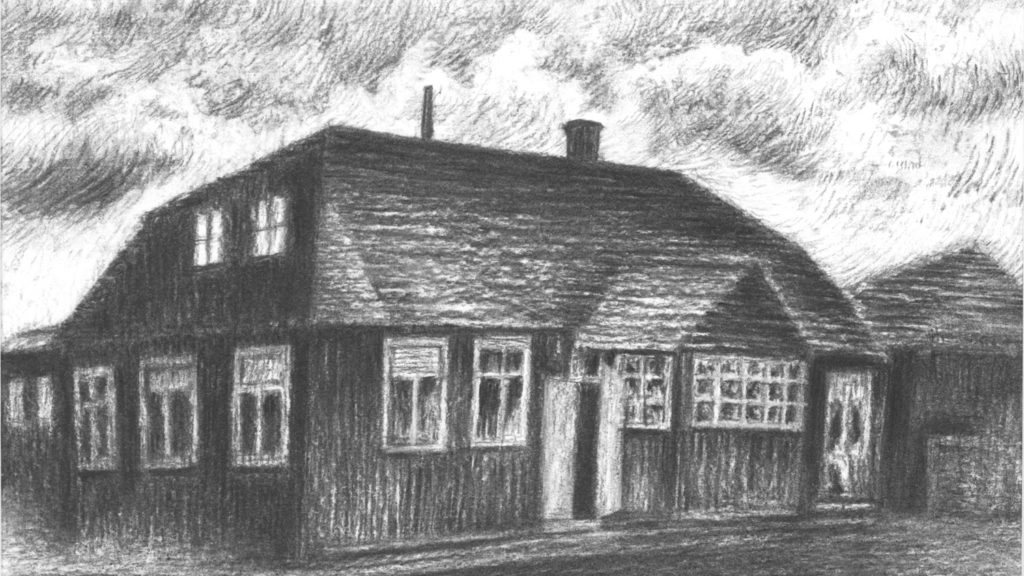

“With a Wolf in One Eye”: Sutzkever in Israel

From his birth just outside Vilna in 1913, Abraham Sutzkever led a life that had merged, as though on a God-ordained path, with the fate of the Jewish people in the 20th century. It of course follows that that life would reach its culmination in Israel.

Necessary Power: A Rejoinder to Jonathan Sacks

When Rabbi Sacks writes, “It is not our task” (and it was not Abraham’s task) “to conquer or convert the world or to enforce uniformity of belief. It is our task to be a blessing to the world. The use of religion for political ends is not righteousness but idolatry,” it seems to me that he oversimplifies matters.

Notice Posted on the Door of the Kelm Talmud Torah Before the High Holidays

In the 1860s, Rabbi Simcha Zissel Ziv tried to found a new kind of yeshiva in which students would devote significant time to thinking about their moral lives.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In