Chaos in the Wilderness

The biblical description of Sinai as “a wilderness” remains accurate. This vast, under-governed space contains tribal societies, criminal smugglers, and—in North Sinai governorate—jihadists. The 1978 U.S.-brokered Camp David Accords made Sinai, between Israel and “mainland Egypt,” into a desert buffer zone, and the region has served as such since the 1979 Peace Treaty. However, the situation in Sinai today has changed, as Israel now encourages Egyptian military operations in Sinai against Wilayat Sinai, a jihadist group linked to ISIS.

As Mohannad Sabry explains in his excellent new book, Sinai: Egypt’s Linchpin, Gaza’s Lifeline, Israel’s Nightmare, Sinai’s separation from the rest of the country “was a natural outcome of it being a military zone” for Egypt’s long-running confrontation with Israel:

But after the signing of the Camp David Peace Accords . . . and following the full Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in 1982, Sinai remained isolated, its Bedouin population marginalized and its development and economy excluded from the rest of the country . . . The war with Israel came to an end, but . . . aside from beachside hotels and resorts, where Bedouin are mostly not allowed to work, the overwhelming majority of the peninsula’s 61,000 square kilometers has remained as lifeless and barren as ever.

The 2011 uprising against the three-decade rule of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak opened the floodgates of Sinai militancy, but Sabry traces it back further. In 2004, terrorists inspired by al-Qaeda attacked the Taba Hilton and nearby beach camps popular with Israelis and other foreigners. After the Taba strike, the State Security Investigations division (SSI) of Egypt’s interior ministry took far more responsibility for Sinai away from the General Intelligence Directorate, which had overseen Sinai security since Egypt’s police first deployed following Israeli withdrawal. In search of the culprits of the Taba bombing, the SSI infamously arrested an estimated 5,000 Bedouins.

Thus began the Sinai population’s tortured relationship with Cairo’s ministry of interior and the police and security services that reported to Mubarak’s minister of interior Habib El-Adly. In Upper Egypt and the Nile Valley, the Mubarak regime’s harsh counterterrorism policies of the 1990s had effectively worked, beating al-Gamaa al-Islamiya and al-Jihad into submission internally, although these groups’ external remnants went on to join al-Qaeda.

In North Sinai, too, after repeated attacks on the tourist cities of Sharm el-Sheikh (2005) and Dahab (2006), the SSI’s brute force managed to quiet the peninsula into submission. The interior ministry’s pre-2011 policies were so harsh that today it is common for Egyptian military leaders, government officials, and diplomats to lament such mistakes, but little seems to have changed.

The early days of the 2011 uprising that eventually toppled Mubarak showed just how deceptive the resultant sense of submissive calm had been. Sabry begins his book by documenting the violent clashes in the North Sinai cities of Rafah, Sheikh Zuwayed, and its capital al-Arish, which pushed the interior ministry’s forces out of Sinai and introduced the security vacuum that continues to this day. What had begun as a tense stand-off between protesters and government forces blocking North Sinai’s main coastal highway escalated after police shot and killed 22-year-old Bedouin activist Mohamed Atef.

As a group of men gathered just outside the town of Sheikh Zuwayed discussed how they should respond to the killing, one of them fired his AK-47 at the town’s fortified police compound, marking the end of “two days of peaceful chanting, hurling rocks, and trying to avoid . . . tear gas” and the beginning of an armed rebellion. Sabry quotes Mostafa Singer, a North Sinai leftist activist who has lived his life just across from that compound: “It wasn’t a protest anymore, by nightfall it had turned into a full-fledged battle; the sounds of AK-47s and the 50 calibers were recognizable. I felt the rocket-propelled grenades rocking the area and clearly heard the armored vehicles racing around.” The gulf between the local population and the security apparatus imposed on them fed the rampage that spread to more North Sinai cities:

To the Bedouins of Sinai, the torched buildings of different police departments represented nothing but the arms of a regime that excluded and oppressed them . . . A history of discrimination saturated the hearts and minds of the Bedouin community with hatred toward the state authorities. Very few police and military officers of Bedouin descent were known to the community, a fact that meant the attackers need not worry their bullets and explosives were being fired at relatives or fellow Bedouins.

Sabry’s interest in Sinai predates his career as a reporter, and his political and tribal contacts in the isolated peninsula make him a valuable resource on a region that is today under an almost complete information blackout. (Full disclosure: The world of current-day Sinai researchers is a small one; I have been acquainted with Sabry since February 2013, when several Cairo-based reporters introduced him to me as the expert on North Sinai.) The peninsula has long been a route for smuggling into Israel and the Gaza Strip. As the book’s subtitle suggests, Sinai has served as a “lifeline” to both the population of Gaza and its ruling Hamas organization.

After Israel’s 2005 withdrawal from Sinai—and especially following Hamas’s 2006 election victory and capture of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit—Jerusalem sought to isolate the strip by limiting its imports. Sabry documents how North Sinai became a boom town for locals, and even for Nile Valley transplants, who took part in the smuggling of consumer goods and building supplies through tunnels under the border into Gaza, where Hamas eventually set up a Tunnels Affairs Commission in November 2008, taxing every item brought in, filling its coffers in the process. But Hamas and the people of Gaza were not the only ones who benefitted from the arrangement, as “one of the poorest and least populous Egyptian governorates . . . became the gateway to a purely consumerist, US-dollar-paying market almost four times its size.” And as Sabry points out, the North Sinai population was less likely to air its political grievances if its economic needs were being met.

The Mubarak regime essentially pretended to be unaware of the smuggling operations, though Sabry’s sources describe a level of both official sanction of such operations as well as corruption. He quotes one 30-year-old part-time smuggler:

“The state security officers imposed their own rules. They took massive bribes and employed the tunnel owners and workers as informants; as soon as it became widely known that the officers were running the business, the lower ranks did the same, even the traffic police took bribes from the cargo trucks loaded with goods on their way to Rafah.”

The Mubarak policy on the Gaza tunnels, which was maintained by the military following his ouster, was two-fold. On the one hand, as Israel set up its blockade of Gaza, Egypt did not want to open the Rafah Border Crossing to commercial traffic, claiming this would violate agreements with Israel. But by allowing trade to thrive underground—both literally and figuratively—the regime could, with a wink, show the Egyptian people it had not abandoned their Palestinian brethren.

But of course the smugglers did not just fill orders for tobacco and fuel; the tunnels also supplied fertilizer and simple chemicals that could be used to make explosives, along with landmines, into Gaza. In time, the most efficient smugglers began handling more lethal items. Indeed, an unintended consequence of Egypt’s acquiescence to the tunnels was that it strengthened links between Egyptian arms smugglers and Hamas, which brought in advanced weaponry from Iran and from post-revolutionary Libya’s stockpiles. Cairo publicly blamed Hamas for militancy in North Sinai and across the country, and Egypt cracked down on the tunnels to sever any such threat. However, Egypt’s counter-tunnel operations actually increased incentives for Hamas to support and assist Sinai militancy.

The security forces’ sweep of North Sinai in the 2000s filled Egypt’s prisons with Sinai militants and criminals-turned-jihadists. The most notorious of these may be Shadi al-Menai, who was imprisoned for trafficking African migrants and went on to be a founding leader of Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (Supporters of Jerusalem), which pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2014.

Al-Menai was released from prison before Egypt’s uprising. In January 2011 he was joined in Sinai by an unknown number of the thousands of escapees who walked out of prisons when the guards left their posts. Over the course of 2011 and 2012, the interim military-led government and, to a lesser extent, then-President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood released other long-standing security detainees, some of whom reportedly returned to fight in Sinai. These included the brother of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri and Mohamed Jamal, the latter of whom was re-arrested following U.S. intelligence linking him to the September 2012 attack on the U.S. compound in Benghazi, Libya. The Sinai Peninsula was effectively lawless.

Although North Sinai was always a distant reach for Cairo, the governorate had channeled law and order through the traditional tribal structure. “Sharia and Tribal Courts” is one of Sabry’s best chapters because of its in-depth look at Sinai’s traditional order, Mubarak-era policy toward that structure, and the rise of Islamic courts in Sinai:

With the arrival of the different tribes to the Sinai Peninsula centuries ago, the elders of the community were the tribal judges . . . The position was seen as sacred so that most judges did not retire, but stayed in their role until death and usually passed their knowledge to their wisest son who would inherit the position.

After Israel withdrew from the peninsula, the Egyptian regime hired a group of Bedouin elders; they became known as “Government Sheikhs.” These faux tribal elites, appointed by the security authorities, lacked the popularity and respect of traditional tribal elders. Dependent on the regime for their authority, the Government Sheikhs were seen as corrupt by the local population. In this context, Sabry introduces readers to Asaad al-Beik, a Salafist preacher in the North Sinai capital of al-Arish who settled disputes on the basis of Islamic law (sharia). Prior to Egypt’s 2011 uprising, al-Beik had been threatened by security forces for running this informal court; but in March 2011 he hung a sign on the guesthouse where the court met identifying it as “The House of Sharia Law in al-Arish.”

Like tribal courts, the sharia courts settle private disputes between parties, but the latter are free to use and subsist on donations. Al-Beik and other sharia judges make all parties sign pledges to uphold the court’s decision. However, the courts also employed what became known as a “Rights Retrieving Committee” for “investigating crimes and violations, verifying testimonies, mediating between rivals, and applying the decades-old naming and shaming system.” The work of these Islamic judges and committees, made up of young Salafist activists selected by the judges, challenged both state and tribal authorities. One source told Sabry the sharia courts and retrieval committees “would have never operated” if the Egyptian state had done its job. The destruction of the tribal order by the Mubarak regime and its replacement with Salafist courts both prepared the North Sinai population for a jihadist call and hollowed out the tribal elites’ ability to effectively respond to it.

Even aggressive Egyptian reporters rarely make it east of al-Arish, and those who do generally serve as mouthpieces for the army or the so-called “sovereign sources” in the peninsula. Indeed, in August 2015 Egypt passed an “anti-terrorism” law that made it a crime to report anything

that contradicted official government statements. With this media blackout, the most recognized alternative to the government narrative is that of Wilayat Sinai, the Islamic State’s Egyptian branch, which spreads propaganda of its operations and alleged governance across social media. By writing Sinai, reporting via Twitter, and making media appearances, Sabry has served as an outlet for the Sinai population caught between insurgent attacks and military response.

Although Sabry’s sources are his biggest asset, they are also his book’s biggest weakness. The military and the militants have obvious interests in playing down or playing up the Sinai fight. Even if we assume the civilian population is interested only in spreading the facts, these are, at a minimum, unverifiable in a war zone, and urban (or rather desert) legends quickly become communal narratives. Sabry corroborates his details with several sources, but in an environment where everyone knows—and talks to—each other, this does not necessarily ensure factual accuracy.

One of the most glaring examples is Sabry’s account of the May 2014 operation that reportedly killed al-Menai, the jihadist leader. By the time of Sinai’s publication Sabry himself recognized that al-Menai was still alive, and it is unfortunate that this story—although a heroic story of local Bedouin standing up to jihadists—made it into the book. Another desert legend is the belief that Israeli unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) regularly circulate over, and take offensive operations in, North Sinai. This is probably a case of the local population being unfamiliar with the capabilities of its own military; aware of Israeli drone operations in neighboring Gaza, Sinai residents hear or see Egyptian surveillance drones and armed Air Tractors and assume they are from Israel.

Sinai’s great strength is that it gives voice to a population that has been ignored at best and silenced at worst. Journalists and researchers in Cairo, Jerusalem, and Tel Aviv often report on official Egyptian and Israeli viewpoints about Sinai. Sabry is one of the few researchers able to present the Sinai viewpoint to a broad audience, and even occasional inaccuracies help present the view the local Sinai population has of Egypt and Israel.

Sinai’s release coincided with the Islamic State’s Sinai branch claiming responsibility for the bombing of a Russian civilian aircraft full of tourists in October 2015. The incident drew international attention to Sinai, to what was happening in the region, and to how such a militant threat developed. Sinai provides thorough answers. Sabry’s engaging narrative, drawing on local sources, introduces the peninsula, its population, and its politics to those who may not have thought about Sinai since the last Egyptian-Israeli war. The rare close Sinai-watcher will appreciate the refresher provided by the book, especially its eight-page chronology and investigations into the dueling narratives of important Sinai-related events.

In his final chapter, “The Imminent Threat,” Sabry laments the current situation in North Sinai. Having provided details of past ministry of interior abuses in the introductory chapters, the book in its latter half documents military operations and government policies in the peninsula since 2011 and especially following Morsi’s 2013 ouster. Egypt’s current military leaders under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi recognize that the interior ministry made mistakes a decade ago and that this “became the seed that grew into a rebellion.” However Sabry meticulously shows these past actions are paralleled by similar ones carried out by the present military regime. Promises to “put an end to six decades of depriving the peninsula’s population of their rights to register the ownership of their land, farms, and real estate,” for example, evaporated. By requiring the population to provide proof that their parents had held only Egyptian citizenship, the government placed an unreachable bar in front of the Bedouin community which “had lived until the 2000s without registering births or marriages, or even obtaining national ID cards.” He concludes that “al-Sisi’s regime may be able to defeat the insurgency with more brutality. But it wasn’t the insurgency that called for, and accomplished, Mubarak’s downfall in January 2011.”

Sabry warns that repression may bring short-term stability, but it creates an inherently unstable situation. Egypt’s government and military give lip service to this insight, but little more. Supporters of Egypt and of Israel who seek a stable and secure Sinai Peninsula between these two U.S. allies should be worried.

Suggested Reading

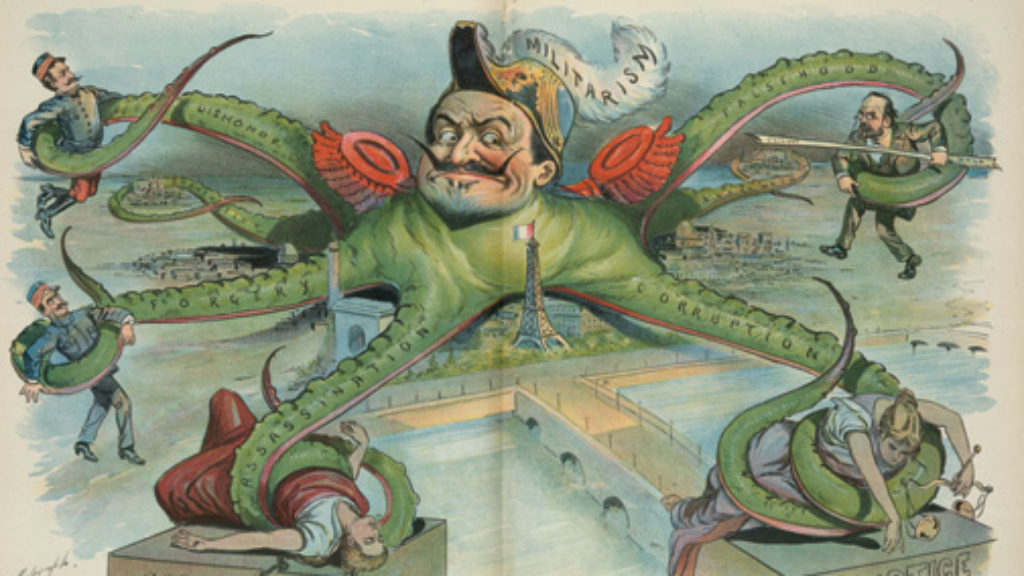

An Affair as We Don’t Know It

Harris retells the “Dreyfus Affair” from Lieutenant-Colonel Marie-Georges Picquart’s point of view, dramatically reconstructing how he zeroed in on the true culprit.

Between Literalism and Liberalism

While literalism is intellectually untenable and liberalism is numerically imperiled, many Jews find that what they believe cannot be transmitted, and what can be effectively transmitted they cannot believe.

The Gentile Jewess

Am I Gentile? Am I a Jewess? Both and neither. What am I? I am what I am.” Muriel Spark at 100.

“The Secret of Our Army’s Endurance”

"I think the army is nothing to play around with, but dabbling in pacifism is a bad business."

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In