Jewish Destiny in a Cheek Swab

Recently, junior congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez invoked distant Jewish roots at a Queens synagogue as a preamble to celebrating the mash-up of Puerto Rican culture and by extension all cultures: “I think what it goes to show is that so many of our destinies are tied beyond our understanding.” Last year, a minor fuss erupted after New York State Senate candidate Julia Salazar made dubious claims to Jewish ancestry.

Such claims, some more credible than others, have been made by various politicians and public figures. Indeed, possible Jewish ancestry has fascinated both Jews and non-Jews when it comes to American historical figures, reaching as far back as Alexander Hamilton (not to speak of my fellow columnist Stuart Schoffman’s fascinating piece on Lincoln). A recent study suggests that one in four Latin Americans has some Jewish ancestry, most likely a vestige of Jewish conversos fleeing the Inquisition to settle in the New World.

There’s something tantalizing about the prospect of uncovering your past with a cheek swab. DNA evidence is refreshingly precise in contrast with the hazy knowledge afforded by family legends and hearsay. Thanks to popular DNA analysis platforms like 23andMe, one can uncover deep connections to hundreds of individuals, of the past and present, whom you have never met. Putting aside the genuinely amazing stories of immediate family reunions that have emerged from 23andMe, the phenomenon also speaks to those with more distant threads to unravel. In one promotional video on 23andMe’s website a Lebanese American man who always wondered about his mother’s gray eyes and his love for Martin Scorsese movies is astounded to learn that he is 9 percent Italian. In that same report he finds some Ashkenazi Jewish heritage as well, a discovery he suggests might hold some promise for peace in the Middle East.

I recently purchased my own 23andMe DNA kit in a Black Friday sale and mailed it in just as Ocasio-Cortez released her Jewish heritage announcement. While I don’t struggle with any glaring mysteries about my past, the thought that these results might offer some new knowledge about myself kindled my excitement. But what kind of knowledge, really? And why the excitement?

When I was younger I enjoyed the novels of James Michener. Michener hit on the formula of depicting a culture by tracking one family over many generations, spanning thousands of years. His novel about Hawaii even starts with the geological formations that comprise the islands, the emergence of its flora and fauna, and finally the arrival of human beings themselves. In The Source, Michener explores the historical strata at a fictional archeological site in Israel, and the descendants of his ancient protagonists end up antagonizing one another in the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Michener turns out to have been adopted, and he spoke about how lack of certainty regarding his own roots led him to feel a sense of kinship with everyone in the world. One’s roots, of course, never extend back in a single line. We each have two parents, and they each have two parents in turn. Our DNA histories look like inverted family trees, and it is inevitable that these branches will reach out and cross or overlap with others. Learning the precise facts of your past may involve unlearning the narrative you know to be true or expand your sense of who belongs in it.

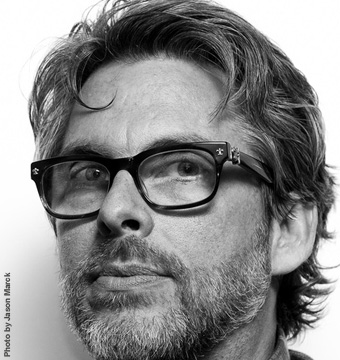

It is therefore unsurprising that another novelist, Michael Chabon, chose to begin his now infamous Hebrew Union College graduation speech with a discussion of the results of the 23andMe test in which he and his wife, Ayelet Waldman, each discovered that they were nearly entirely Ashkenazi Jewish. In the speech, Chabon rambled on passionately about the dismantling of all walls and boundaries—between countries, Jews and non-Jews, prisons and the world outside them—in the pursuit of a more heterodox and inclusive future. Chabon, in his own parochial universalism, failed to consider the fact that many of these boundaries are precisely what allow for individual identities and cultural exchange to exist in the first place. Chabon’s shallow misuse of Yiddish terminology (haredi Jewish agitators are “ganefs”) despite his claim to be haunted by the “dybbuks of Yiddish” (another cliché if there ever was one) ironically reveals how the effacement of boundaries he seeks actually amounts to erasing difference altogether.

Despite Chabon’s newfound disapproval of endogamy, he and his wife “married in”—a fact he can now lament with full scientific confidence. As with Ocasio-Cortez’s speech, the concrete revelation of one’s Jewish identity thanks to DNA evidence actually becomes the starting point of undermining Jewish particularism.

I could be wrong, but I don’t think that other ethnic groups exhibit this peculiar self-negating dynamic. Take, for example, Yaa Gyasi’s recent hit novel Homegoing. The novel traces eight generations in the family histories of two half-sisters in 18th-century Ghana—one is sold into slavery in the U.S., and one remains in Africa as mistress to a powerful British officer. The American branch of the family lives through a range of devastating experiences that exemplify the historical black experience in America: slavery, unjust imprisonment, Jim Crow, and even the dissolution of a modern family due to drug addiction. Gyasi’s characters are deprived of not only their freedom and well-being but also their links to their past and to each other. The novel in turns provides the genealogy that they lack—a 23andMe-style history to replace the one that was stolen from them.

Of course, even in this instance, choices are made. Despite the curious fact that nearly every family in the novel has exactly one child, which creates the illusion of a straight line, the nature of biology is such that the 8th-generation descendants of the original sisters have about as much DNA linking them to their ancestors as they would to thousands of people across the globe. Nevertheless, in Homegoing genealogy is the beginning of a meaningful relationship to one’s past. It’s a striking contrast to Michael Chabon’s call for a postreligious, postnational future.

Michener told a syncretic story of overlapping Canaanite, Jewish, Babylonian, Roman, Arab, and Babylonian cultures in The Source, but he ended with “the law”: “It was no mean thing to be a Jew and the custodian of God’s law . . . There could be no larger task.” A little later, his protagonist Eliav reflects, “We seek God so earnestly . . . not to find Him but to discover ourselves.” Even the archeologists in this novel seem to conclude that their greatest self-knowledge will derive from living a life of purpose rather than excavating and reconstructing layers of a distant past.

As to how my own 23andMe foray turned out: Like Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman, I am as Ashkenazi Jewish as they come. While, sadly, no members of the Chabon family feature in my closest circles, I was intrigued to see my husband’s best friend turn up as a possible second or third cousin along with the prominent Israeli psychologist Dan Ariely. Aside from some underwhelming additional genealogical data, such as a high likelihood of enjoying coffee or a rather strong, 90 percent chance of having wet as opposed to dry earwax, I left the experiment not knowing much more about myself than when I started.

It is true that a boring family tree is itself something of a historical feat: the product of centuries upon centuries of one’s ancestors holding fast to one’s community and faith despite dispersion and dislocation. And even in my own relatively homogenous circumstance, there are tragic Holocaust-related gaps that invite further research, lost branches of the family to find. When one’s roots have been torn away, DNA evidence, like Michener’s historical tales, can be a healing balm. But for those who seek a deeper Jewish identity, the results of these cheek swabs are superfluous. And in the hands of those uninterested in such an identity or fleeing from it, they are yet another platform on which their personal and familial pathologies can play out.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Limits of Prayer

One who prays to change the past, says the Mishnah, “utters a vain prayer.” A person should not beseech God to undo events that have already taken place, even when the outcome is still unknown. And yet there are circumstances where one is naturally tempted to do just that.

Category Error: A Response & Rejoinder

Yoram Hazony responds to Jon D. Levenson's critique of his book. Levenson replies.

Politics and Prophecy

Ari Shavit, the Israeli prophet-journalist, offers both rebuke of the past and warnings for the future, but unlike prophets of old, he has no solutions for the way forward.

In Pursuit of Wholeness: The Book of Ruth in Modern Literature

While not the most dramatic of all the biblical stories, the quietly moving book of Ruth, which we read on Shavuot, continues to resonate in Western literature.

Nadia Kahn

test

Katherine H. Baker

I began reading Sarah Rindner's article with a sense of fear and trepidation. "Oh no. Here is another individual so fascinated with DNA technology that they only will see the use of molecular tools to find bits of ethnic groups in individuals - X% Italian, Y% Jewish, Z% Icelandic etc." Our society, fueled by the slick commercials of 23 and me and similar companies, is using the findings of DNA to revive old, outdated, and discredited ideas of race and ethnicity. As a Biology Professor (retired) who has taught evolutionary biology, I know population-wide DNA studies (more properly called genome-wide-association-studies or GWAS) demonstrate that there are no clear biological/genetic differences between groups of people. Yes, certain traits are more likely to occur in certain populations or ethnic groups (thing Gaucher's disease in Ashkenazi Jews) but this is a statistical association. There is a single human race with an immense and fluid gene pool. Thus, when 23 and Me says someone is 9% Italian what this really means is that 9% of the identified gene sequences in that individual's DNA are similar (at a statistically acceptable level) to a sequence that is found in a higher than average percentage of the gene sequences of individuals with Italian ancestry. At best, this is a fuzzy association, not a firm number.

Ridner's essay underscores the error of the distinction DNA companies, and our fascination with DNA, represent. Ethnic identity, at least over a multi-generational time-scale, is a matter of family, community, and culture - not of DNA. We need to understand the biological unity of all humans while at the same time embracing the ethnic and cultural diversity that is the result of human history. Ridner's essay sees this clearly. I wish more people shared her perspective.