Ungoverning the Western Wall

Last Friday, March 8, was the 30th anniversary of Women of the Wall, a multi-denominational Jewish feminist group that has made it its mission “to attain social and legal recognition” of the right of Jewish women “to pray collectively and read aloud from the Torah at the Western Wall while wearing prayer shawls.” When Jewish women from Israel and abroad arrived at the Wall to celebrate the anniversary, they and their male supporters found themselves confronted by large numbers of haredi Jews, including young women who had been bussed in from religious high schools. Ugly clashes ensued, followed by charges and countercharges of provocation, and, of course, widespread news coverage.

This is not the way things were supposed to be. When the Israeli government decided three years ago, in January 2016, to establish a new egalitarian prayer plaza at the Wall, liberal Jews rejoiced, and the Women of the Wall decided to accept this new compromise. But a year and half later, in June 2017, under heavy pressure from haredi parties, the Israeli government decided to postpone—and, in effect, abandon—the implementation of what Prime Minister Netanyahu had originally called a “fair and creative solution.” The immediate reactions of major Jewish communities and organizations in the United States to the government’s retreat from its initial decision were dramatic enough to threaten a rift between Israel and U.S. Jewry.

Eventually, the political furor over the failed compromise abated, as will the one over last week’s clash. But what comes next? Will yet new compromise proposals be floated, perhaps even adopted, and then shot down? In the volatile world of Israeli politics, it is hard to say. It is easy, however, to imagine the problem persisting indefinitely, poisoning deliberations in the Knesset and Israel-diaspora relations for decades to come.

The present arrangements at the Wall are the result of two laws, passed in 1967 and 1981 respectively. These laws classified the Western Wall as a sacred site administered by a state agency, the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, under the authority of a state employee, known as “the Rabbi of the Wall,” an office currently held by haredi Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz. The plaza in front of the Western Wall has been divided into two uneven sections: the larger area has been set aside for men’s prayer and the smaller one for women’s prayer. While persons of different faiths, or of no faith, can visit the Wall and even pray after their own fashion, the 1981 law bans religious practices that create “offenses to the feelings of the praying congregation” in order to maintain the “custom of the place” (minhag hamakom); both contested concepts with major implications for religious liberty and gender equality.

This conflict has led to the formation of several governmental committees and three Israeli Supreme Court decisions (delivered in 1994, 2000, and 2003). But the legal situation did not change until 2013. In a groundbreaking decision of the Jerusalem District Court, Judge Moshe Sobel upheld the rights of the Women of the Wall to pray at the plaza in accordance with their custom. He argued that their manner of prayer neither opposed the “custom of the place,” according to a broader interpretation of the term, nor offended the praying congregation. Liberal, Reform, and Conservative Jews—and of course Jewish feminist groups—greeted Sobel’s ruling with enthusiasm, but haredi political parties vehemently opposed the decision. Rabbi Rabinowitz has used various semitechnical regulations in order to circumvent full implementation of Judge Sobel’s ruling.

In response to pressure from both sides, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s cabinet approved a compromise plan in January of 2016: a third plaza, south of the current Wall plaza would be established at the foot of Robinson’s Arch as an egalitarian prayer space, without the permanent separation of men and women. The Rabbi of the Wall and the Western Wall Heritage Foundation would have no authority over this new plaza, which would be under the management of a new council that would include women and representatives of Reform and Conservative Judaism. At this new plaza, women who would prefer to pray separately could still use a temporary partition. Meanwhile, the central plaza would revert to the arrangements that had prevailed prior to Judge Sobel’s decision. This is the ambitious plan that was effectively canceled in June 2017. And so we have returned to shoving, spitting, angry words, and worse in Judaism’s holiest place.

What is the best way to govern such a contested sacred site? Our answer is: (almost) not at all. The government should adopt an approach of noninterference, restricting itself to providing law and order. It should abolish the position of the Rabbi of the Wall, cancel bans on religious activities on account of their supposedly offensive nature, dismantle the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, and remove the permanent mechitza (temporary, portable dividers would remain permissible). Simply put, all matters of religious decision making at the site would lie with the individual rather than with the state.

While no solution is perfect, such an approach to the Wall has many merits: It does not restrict the religious liberties of any one group; it unburdens the Israeli government from a contentious entanglement with religion that threatens its relationship with American Jewry, and, most importantly, it distances the state from the sacred, protecting religion from the corruption of state authority and power.

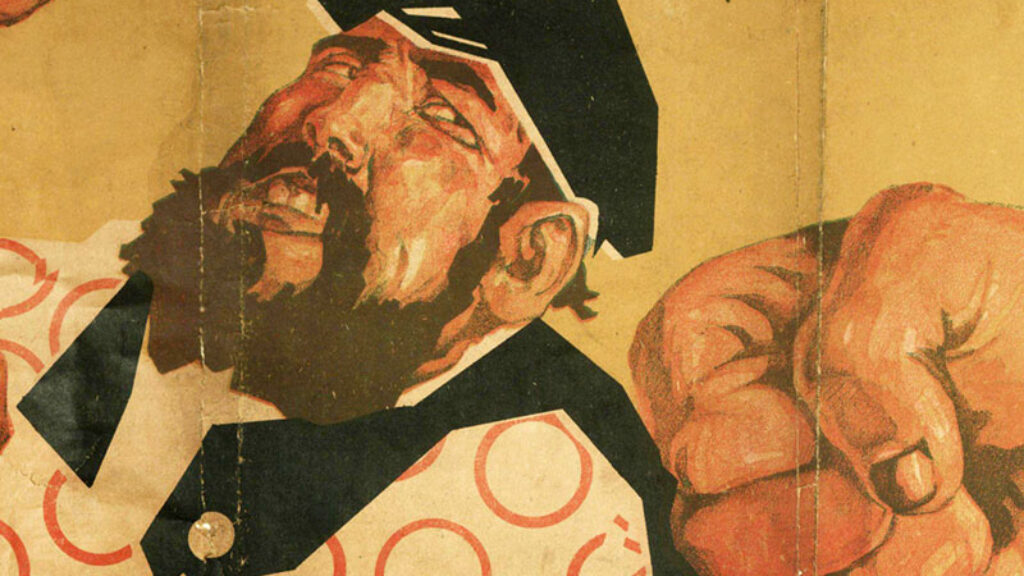

Early 20th-century photos of Jews praying at the Western Wall often show men and women standing side by side, each communing with God individually. It is probably too nostalgic to hope that we can return to such comity. In the meantime, we see no better alternative than ungoverning the sacred.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Bread and Vodka

Mendel Osherowitch's 1933 book about life in Ukraine not only bore rare eyewitness testimony to one of the worst atrocities in a barbarous century; it did so from the vantage point of a brother of two of the perpetrators.

Himmelfarb, George Eliot, and the Jews

English philo-Semitism, in fiction and reality.

Cannon Fire Over Sarajevo and Sin in Ansbach: A Passage from Rabbi Jacob Emden’s 18th Century Memoir

Jacob Emden get a deserved, if belated, translation into English.

The Sounds of Silence

In his latest book, John Gray, himself a nonbeliever, takes atheists to task for trying to convince themselves that the world is organized according to an intelligible principle—a proposition he believes they inherited from monotheism.

Dr. Norman Gold

Folks, I am generally in favor of not having government involved with religion, even in Israel. For example, I feel that if someone wants to take a bus on Shabbat, they should be able to. After all, if someone does not want to, he doesn't have to, and the fact that someone else does, in no way impacts his own religious convictions and practice. The fact that the Orthodox would have to SEE the buses in no way restricts their free practice of their own Orthodox ways and customs.

But when it comes to the Kotel, as well as other sacred, holy sites such as Me'arat Hamechpela and Kever Rachel, I most definitely do NOT agree with you. You state, "It does not restrict the religious liberties of any one group" to allow for totally mixed crowds at the Kotel. But that is simply NOT true; a minyan of Orthodox males CANNOT pray in the presence of women. That's just a fact, and one which proves your statement to be absolutely false. The fact that you can show an old nostalgic picture of the Kotel with women praying beside the men is totally irrelevant to this argument; just because something was common practice does not mean that everyone felt free to participate.

As the situation is now, EVERYONE can pray at the Kotel. Conservative and Reform Jews may not LIKE having to pray either with a mehitza, or further back in the Kotel Plaza where there is no mehitza. But that does not in any way whatsoever prevent them from praying there. So, with the status quo - ALL Jews can pray there, and at all holy sites in Israel. Hey - nothing in Israeli law guarantees that everyone will always be fully satisfied with every aspect of the law, as long as it allows everyone equal freedoms. The fact that Conservative and Reform Jews don't LIKE the arrangement does not in any way restrict their ability to exercise their right to pray. But your "solution" DOES restrict the rights not just of the Hareidi community, but even of the modern Orthodox that also pray only with separation of men and women.

Israeli law allows people to smoke. But if I'm on a bus and I want to smoke, I have to get off the bus. Why? Because my smoking will restrict the right of the non-smokers to enjoy a smoke-free bus ride. But wait a second - doesn't that make me, as a smoker, a second-class citizen to the non-smokers who get to stay on the the bus? Only a fool would think that - what gives me the right to force you to inhale my smoke? If I want to smoke, I can always get off the bus.

What gives the Conservative and Reform movements the right to restrict my ability to pray at the Kotel? And your brilliant "solution" does precisely that. I say leave the status quo. It is the ONLY way that truly allows ALL Jews to freely pray at the Kotel and at other holy sites. If the Conservative and Reform "smokers" don't like it, they can always get off the bus.....

Joseph Shier

The writers are correct that the photo they use to support their position shows men and women standing together. They neglect to point out that the photo also shows people sitting on the ground and that while those standing at the wall are, in their words, each communing with God individually, the normal Jewish communal prayers are absent from the photo, as they are from, I believe, all other photos taken. The Turks, I understood, ensured even a bench would not be brought to the wall as it might be used for a division between men and women and then those Jews would start their normal, traditional communal prayers. Jews, you see, were to be kept in their subservient position.

When the Jordanians lost their control over the old city of Jerusalem, only some Jews began to conduct traditional communal prayers at the wall. Was their action a mark of social divisiveness or of self-respect, of pride in the Jewish renewal of self-rule and of honour of a millennial tradition? Are the writers sure that disallowing communal prayer, i.e., returning to the Ottoman days, is the progressive answer?

Kalman Neuman

The authors obviously have not ever visited the Wall, or are totally oblivious of Orthodox Jewish practice. There are thousands of Orthodox Jews who pray at the Wall almost 24/7. They cannot pray without gender separation. There have to be some rules and standards , or else the place will one of total chaos.

Rabbi Jonathan L. Hecht, Ph.D.

Dear Dr. Gold,

Before you kick me and the majority of Jews off the bus, you might address the issue of why the Haredi parties objected to the compromise plan of January 2016.

The compromise plan sought to establish a separate area where egalitarian prayer could take place. That plan, sadly, did not create a space for egalitarian worship at the Kotel, however, it did create an adjacent prayer space. Many thoughtful non-orthodox (and some Orthodox) Jews agreed to have our rights restricted by this compromise agreement. The actions of the Haredi political parties and the Rabbi of the Wall and the Western Wall Heritage Foundation make it eminently clear that this goes beyond what you advocate: that this is just about the rights of Orthodox Jews to pray with a mechitza. Their actions make it very clear that this is about preventing Reform, Conservative, egalitarian Orthodox Jews and women from exercising their rights to pray as Jews in one of Judaism's most holy sites.

I agree with the authors of the article. The government of Israel has no business being involved in determining how Jews pray at the Kotel and should dismantle the Haredi control over this national Jewish symbol. The reprehensible actions of Haredi Jews at the Kotel... attacking, insulting, and preventing the prayers of women and egalitarian Jews, undermine the religious nature of this site. What is their next move? Murder?