Seventy Years in the Desert

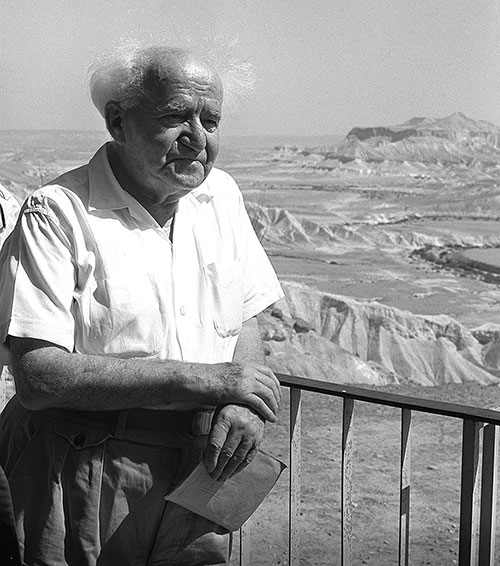

Sometime around 1965, I took a bus to New York City for a round of the International Bible Contest, not to compete but to cheer on a high-school friend. My main reason for going, however, was to see David Ben-Gurion, who was scheduled to pose some of the questions to the contestants. All I can remember now are the two that he addressed, in his trademark high-pitched shout, to the entire audience: “How many of you are ready to make aliyah to the Land of Israel?” And then, more specifically, “How many of you are ready to come and live with me in the Negev?”

The recently retired prime minister’s questions certainly weren’t in the spirit of his famous 1951 promise to the American Jewish Committee’s Jacob Blaustein not to play Pied Piper to idealistic Jewish youngsters in this country. But Blaustein, had he been present, would not have been worried. Only a few people raised their hands in response to the first question, and no one at all did so after the second one.

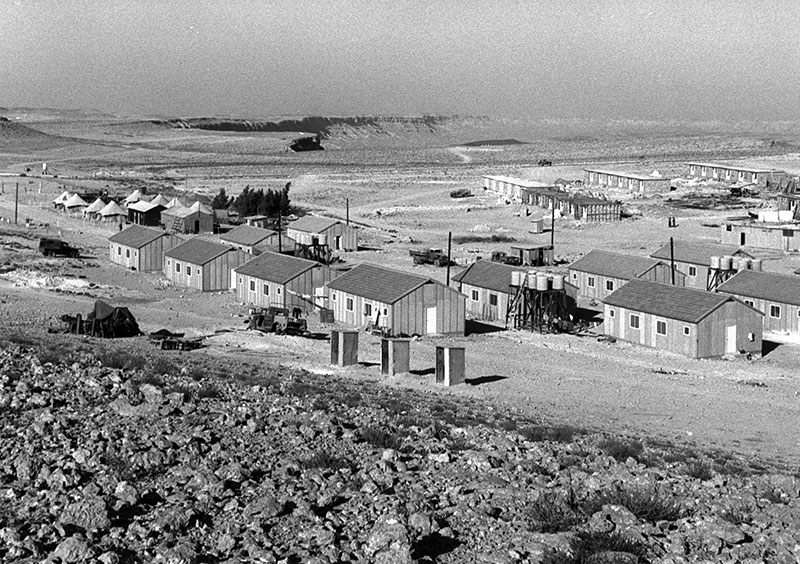

This isn’t too surprising, given the Negev’s mostly empty and severe terrain, its aridity, and its notoriously hot climate. Indeed, Ben-Gurion hadn’t had much better luck in Israel itself than he did in New York. As Yael Zerubavel reports, he had, while prime minister, “championed the national goal of ‘making the desert bloom’ [but] there was a limited response to this call.” Most of the Jews who came to settle in Israel’s south in the first two decades after the establishment of the state did so involuntarily. Immigrants, mostly from Arab countries, were transported “directly from the boat to their designated settlement in the Negev in order to minimize the possibilities for them to object to this plan.”

In fact, some were smuggled into their new homes in development towns in the dead of night to prevent them from being alarmed by the desolation all around them. Those who arrived in daylight would sometimes refuse to disembark. On such occasions, Zerubavel writes, “the driver would raise the truck on a slant ‘and they were poured on the ground. The truck would leave, and the people remained on the ground.’”

Zerubavel is far from alone in highlighting such bleak moments in Israel’s history. But her book is not another indignant exposé of statist manipulation of distasteful “human material.” She writes not to condemn nor, for that matter, to celebrate the policies pursued by Israeli leaders in the 1950s but to situate them in the context of a broad range of “complex and contradictory” Zionist stances toward the desert in general and the Negev in particular.

The biggest of the many contradictions Zerubavel discusses is between the Zionist longing to transform the desert and a longing to be transformed by it. The celebrated poet Natan Alterman, for instance, wrote “The Road Song” (1934), in which a road builder sings, “Wake up, wasteland, your verdict is decided / We are coming to conquer you!” The less well-known, countervailing tendency reflects the susceptibility of some Zionists to a “desert mystique,” which imagined both “the ancient Hebrews and the contemporary Arabs as close to nature, a quality that had been lost to Jews during centuries of life in exile.” In a 1912 story by Yosef Luidor, “a native Hebrew boy . . . rebels against school and adult authority, preferring to ride his horse and spend time with the Bedouins.” His immigrant Jewish friend sees him as “a desert figure whose black eyes burn with a strange, wild fire.” A little later there was the real-life Pesach Bar-Adon, an oleh from Poland who dropped out of the Hebrew University in the mid-1920s to live with the Bedouins as an apprentice shepherd.

In the course of time, however, the Negev itself has been transformed more than the Jews who settled there. While development has not taken place on the scale or in the way that Ben-Gurion imagined, Israel has, in fact, made a large swath of the desert bloom. Beersheva has grown into a sizeable city, and its satellite suburban communities have flourished. Surprisingly, despite the fact that the Beersheva region contains more than half of the Negev’s Jewish population of 422,000, Zerubavel devotes only a few scattered paragraphs to it, focusing instead on smaller but more exotic developments, such as urban kibbutzim in development towns such as Sderot, new residential religious settlements in the center of the Negev, and the unusual expansion of individually owned farms.

Much of the impetus to enhance and diversify Jewish settlement in the Negev has stemmed, in recent years, from what Zerubavel describes as the fear that “the fast-growing Bedouin population in the Negev posed a demographic and security threat.” The Bedouin population has mushroomed from around 12,000 after the exodus that took place during the War of Independence to around 170,000 in 2007 and to 249,800 in 2016, more than a third of the total population of the Negev. The Israel Land Administration projects that their population will reach 300,000 by next year (the Negev Bedouins have one of the highest natural growth rates in the world). Jewish fears that they will someday become a majority in the area are based, it seems, on real statistics. But are the Bedouins a security threat?

As is well known, some Bedouins volunteer to serve in the Israeli army, but their numbers, as Zerubavel observes, have remained small (between 5 and 10 percent of the draft-age population) and are decreasing. This is largely a reflection, according to Zerubavel, of festering inequalities in the towns to which thousands of Bedouins were forcibly removed and the state’s refusal to legalize the “unrecognized villages” in which 100,000 Bedouin residents lack “the basic infrastructure of roads, running water, a central sewage system, electricity and public transportation to which legal settlements are entitled.” Dislocated, alienated, and impoverished, the Bedouins are becoming increasingly inclined toward religious fundamentalism and political radicalization.

This volatile situation has sparked fears that the Negev will be the scene of the next intifada. After quoting a number of newspaper headlines that warn of such a development, Zerubavel summarizes Tzur Shezaf’s 2007 Hebrew novel The Happy Man, about a revolt led by two Bedouins, a neurosurgeon and a high-ranking IDF commander. Disillusioned “by the state’s coercive measures against their people,” they launch a peaceful protest that soon escalates into a war that lasts for two years and culminates “in the destruction of the Bedouin villages and the expulsion of their residents across the border to Egypt.”

While taking note of such nightmares, Zerubavel does not prophesy catastrophe. Here and there, she even sees bright spots. Things seem to be better in urban environments than in rural ones, especially in Beersheva, which “presents a range of formal and informal opportunities for Jews and Bedouins to interact,” including Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and the Soroka Medical Center.

Zerubavel also provides evidence that the early 20th-century “desert mystique” isn’t entirely gone. She notes that Jewish desert tour guides often wear white kaffiyehs, and the website for the New-Agey Desert Ashramin the southern Negev promises visitors that they can “connect to your inner Bedouinand stay in a genuine wool tent.”

Yael Zerubavel teaches at Rutgers, but she wrote most of Desert in the Promised Land at the Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism in Sde Boker, near Ben-Gurion’s own kibbutz in the heart of the Negev. Pnina Motzafi-Haller, an anthropologist at Ben-Gurion University, lives and works in Sde Boker, but her new book, Concrete Boxes: Mizrahi Women on Israel’s Periphery, focuses on the nearby development town of Yerucham, which is a symbol, throughout Israel, of socioeconomic

failure.

It is also the home of the Mizrahi women who cleaned her office, and she would often schmooze with them there around 11 a.m., “after they have finished the first part of their daily cleaning rounds and before their lunch break.” However, MotzafiHaller did the bulk of her research in Yerucham itself, where she interviewed a large number of men and women. In the end, she decided to focus her book on five women whose lives reflect “the reproduction of ethnic-and class-based inequality in Israel over three generations.” The story she has to tell is both fascinating and surprising.

Motzafi-Haller’s subjects are all the descendants of the people who were unceremoniously dumped in the desert half a century or more ago. Some of them have risen above the unfavorable circumstances—including homes in apartment blocs that are nothing more than “concrete boxes”—into which they were born, but others have never escaped them or have done so only for a short time. Motzafi-Haller herself comes from a background similar to theirs, and she openly empathizes with them. In the course of writing the book, she tells us, her “position within the research, as a Mizrahi academic woman straddling the lines between ethnic belonging and class borders, took center stage.”

While she depicts the material hardship and aimlessness of many of her subjects’ lives, Motzafi-Haller is also eager to demonstrate the extent to which some of the women take their lives into their own hands, exercising real “agency” even when it doesn’t quite work. Take Esti, for instance, the child of immigrants from Morocco in the 1960s who has worked on and off as a cleaner for most of her life. A single woman with shaky finances who largely survives on welfare and money derived from unclear sources, she insists on living flamboyantly, well beyond her means, and has had to deal with the consequences. Observing her unnecessary purchases, Motzafi-Haller oscillates “between an accepting, inclusive stance from which I cheer on Esti’s wild revelry, and a middle-class, moralist, external positioning that asks her to be serious.” Motzafi-Haller never loses sight of Esti’s self-sabotage, but neither does she cease to see in her “a spirited rebel, who develops clear means of survival . . . that allow her to cultivate self-worth in a reality that seems designed to deny her . . . such dignity.”

Of all the options available to her subjects, however, it is not rebellion but “religious strengthening” (hit’chazkut) that Motzafi-Haller regards as the “most constructive,” an attempt to transform, or at least better, their lives, rather than escape them. “The act of participating in religion classes marks them as serious, respectable women with high spiritual aspirations, not gossips who spend their evenings watching shallow soap operas on television.” This can lead not only to greater peace of mind but also to new patterns of consumption. Motzafi-Haller quotes one woman:

“Religious women are different from us financially. They manage with what there is. They’re more careful with money. They don’t go to some boutique. They don’t buy stupid things. No Digimon or Pokemon. No TV or PlayStation. They invest more in their children.”

Motzafi-Haller tells us about going to an interview at a nursery school in Sde Boker with one of her subjects, a mitchazeket named Efrat. At the school, they ran into Efrat’s older sister, a part-time cook and cleaner. The nonreligious sister’s tight purple pants and loose, faded sleeveless shirt contrasted starkly with Efrat’s modest dress, which radiated respectability. Efrat got the job.

Motzafi-Haller is, we shouldn’t forget, an unabashedly secular woman. Her recognition of the beneficial aspects of religiosity is neither pious nor apologetic. She sees hit’chazkut as just the best available option for women like Efrat who have been failed by “liberal and neoliberal efforts to break Yerucham’s intergenerational cycle of poverty and social isolation.”

Things have turned out very differently from what David Ben-Gurion was imagining when he urged a bunch of American Jewish teenagers to come and join him in the desert. As both Yael Zerubavel and Pnina Motzafi-Haller demonstrate in their different ways, Israel’s effort to conquer the Negev has been incomplete and plagued with unintentional consequences, but they also both provide reasons for hope.

Suggested Reading

What’s Yichus Got to Do with It?

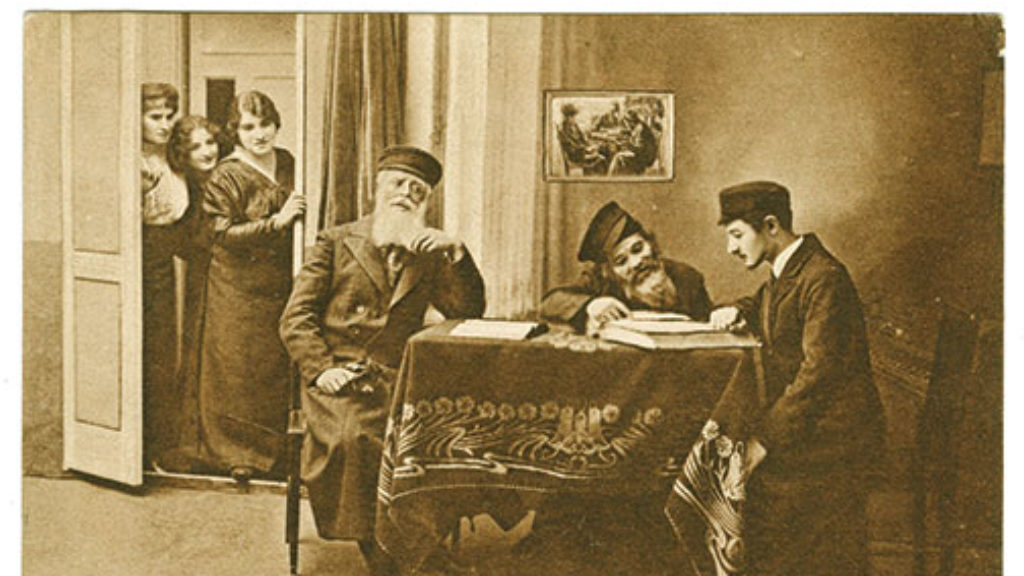

For the whole history of Jewish society, until less than two hundred years ago, love and attraction played little or no role in the making of marriages, which were arranged and contracted according to the interests—commercial, religious, and social—of the families involved.

It Was Like This: Excerpts from an Academic Memoir

Scenes from Anita Shapira’s gripping memoir.

A Little Arabic within Our Hebrew

Tracing lines of a linguistic heritage through Hebrew poetry.

The Founder of Jewish Studies

In 1818, a 23-year-old university student named Leopold Zunz published a 30-page essay with the modest title “On Rabbinic Literature.” He could scarcely have imagined his impact.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In