Harold Bloom: Anti-Inkling?

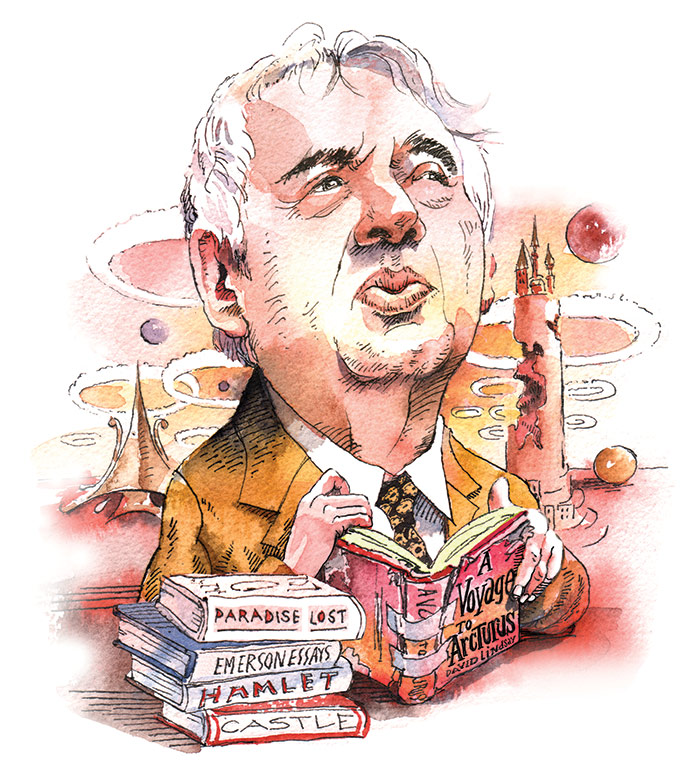

It’s a bit surprising to come across Harold Bloom’s confession that the literary work that has been his greatest obsession is not, say, Hamlet or Henry IV, but a relatively little-known 1920 fantasy novel. After all, Bloom is our most famous bardolater. When I took an undergraduate class with him at Yale, he announced his trembling bafflement before Shakespeare’s greatness in almost every lecture. In the course of his career, Bloom has named a handful of other literary eminences who compel from him a similar obeisance—Emerson, Milton, Blake, Kafka, and Freud are members in this select club—but one does not find David Lindsay on this list.

Yet, in his 1982 book Agon: Towards a Theory of Revisionism, Bloom writes of Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus: “I have read it literally hundreds of times, indeed obsessively I have read several copies of it to shreds.” The much-shredded book has, he says, “affected me personally with more intensity and obsessiveness than all the works of greater stature and resonance of our time.” In fact, Bloom wrote his own fantasy novel—The Flight to Lucifer, published forty years ago this year—in apparent response to Lindsay’s. “I know of no book,” he writes, “that has caused me such an anxiety of influence, an anxiety to be read everywhere in my fantasy imitating it.”

What is it about A Voyage to Arcturus that so captivated Bloom? Though it never had much mainstream success, Lindsay’s genuinely strange and unsettling novel surely belongs on any list of the twentieth century’s most significant works of fantasy. The trendsetting British fantasy novelist Michael Moorcock, writing in 2002 on the occasion of one of the book’s republications over the years, called A Voyage to Arcturus a “Nietzschean Pilgrim’s Progress” and praised its “compelling, almost mesmerising influence.”

A Voyage to Arcturus opens with a drawing-room séance interrupted by three strangers: the threatening Krag, his glum companion Nightspore, and the novel’s protagonist, Maskull, who joins the first two on a journey to the planet Tormance. While exploring Tormance, which is ruled by an entity known as Crystalman, Maskull ends up sprouting a series of odd new limbs, eyes, and sensory organs. His often-fatal encounters with the planet’s inhabitants read as mythic allegories of everything from the search for God, to the relationship between the sexes, to the artistic process.

Bloom, though, views Lindsay’s novel as a kind of spontaneous Gnostic scripture. In his reading, Crystalman is the oppressive god, or demiurge, who according to Gnostic theology keeps us locked in the material world and ignorant of our radically free natures. Whether or not this is what Lindsay had in mind, in The Flight to Lucifer Bloom makes the Gnostic content didactically explicit.

In Bloom’s version, the alien planet Lucifer is inhabited by warring tribes named for ancient Gnostic sects: Marcionites, Mandaeans, Sethites, etc. Lindsay’s Krag is renamed Valentinus, after the much-reviled 2nd-century Gnostic theologian. Meanwhile, the Maskull substitute, Thomas Perscors, has been turned by Bloom into a poor cousin of Conan the Barbarian. He battles the planet’s demiurge with sword and shield but more often struggles to escape the sexual snares of several monstrous yet alluring female deities.

In deference to his scholarly reputation, reviewers tried to be forgiving, but most judged Bloom’s novel turgid. A typical example of the dialogue:

Valentinus nodded as he rose. “This rocky world is a battered affection of the Pleroma. When the inwardness fell away from itself, through the passion of Achamoth, this became its furthest reach, outward and downward.”

“This abides through ignorance,” Olam rejoined, “but the ignorance is only our knowledge reversed. This materiality will pass.”

The book is filled with snappy exchanges like this one. Writing at the time in the London Review of Books, Marilyn Butler summed it up as follows:

As fiction, The Flight to Lucifer has practically nothing to recommend it. The plot, so important an element in fantasy, lacks suspense, pace and variety. . . . Lucifer is not a fictional world for the imagination to linger in: the landscape is repellent, the light poor, and the native inhabitants both nasty and feeble—while the visitor Perscors, angry, murderous, exceedingly male, is about as empathetic as King Kong.

I wouldn’t call Perscors “exceedingly male,” but I agree with Butler that “it is hard not to speculate, in ordinary Freudian terms, about this character’s obsession with punishing a succession of elderly and uninviting whores.” Bloom’s novel features a cringeworthy orgy and several S&M scenes that are even more soporific than the dialogue quoted above.

In Agon, Bloom grudgingly acknowledges some of his novel’s shortcomings, remarking that it “reads as though Walter Pater was writing Star Wars.” (This may be generous.) Yet Bloom also announced that he was at work on a second fantasy novel, entitled The Lost Traveller’s Dream. It has never appeared, and, when I encountered Bloom in that classroom in the late 1980s, he enjoined his students to burn any copies of The Flight to Lucifer we might come across.

According to Bloom’s famous theory of the “anxiety of influence,” we don’t get to choose our influences. Moreover, a writer’s explicit designation of a major influence is usually a ruse, intended to hide (mostly from himself) the real influence at work. By his own lights, then, Bloom’s explanation of The Flight to Lucifer as an anxious response to Lindsay deserves a second look.

It seems significant in this regard that, in the same chapter of Agon in which he reviews his own novel, Bloom holds up Lindsay as a counter to the fantasy writers known collectively as the Inklings: J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and Charles Williams. With his trademark portentousness, Bloom announces that Lindsay’s The Voyage to Arcturus is

at the very center of modern fantasy, in contrast to the works of the Neochristian Inklings which despite all their popularity are quite peripheral. Tolkien, Lewis and Williams actually flatter the reader’s Narcissism, while morally softening the reader’s Promethianism. Lindsay strenuously assaults the reader’s Narcissism, while both hardening the reader’s Promethianism and yet reminding the reader that Narcissism and Promethianism verge upon an identity. Inkling fantasy is soft stuff, because it pretends that it benefits from a benign transmission both of romance tradition and of Christian doctrine. Lindsay’s savage masterpiece compels the reader to question both the sources of fantasy, within the reader, and the benignity of the handing-on of tradition.

As Bloom never clearly defines “Narcissism” or “Promethianism,” nor explains his assertions by offering examples from any of the authors concerned, it is not entirely clear what he means here. Evacuated of its gassiness, his argument amounts to a preference for romantic rebellion to religious tradition.

Interestingly, C. S. Lewis admired David Lindsay and called A Voyage to Arcturus “that shattering, intolerable, and irresistible work,” a fact which Bloom avoids. Bloom does quote from Lewis’s encomium to the 19th-century fantasist George MacDonald, whose books offer an experience that, in Lewis’s words, “gets under our skin, hits us at a level deeper than our thoughts or even our passions, troubles oldest certainties till all questions are reopened.” Bloom responds to this by saying that he believes he understands what Lewis is describing, but judges it applicable only to Lindsay.

Given these swerves, gaps, and evasions, it starts to look as if it was actually the Inklings, and especially Lewis, who got under Bloom’s skin. Is Bloom’s obsession with Lindsay a screen for a more anxious relationship with Lewis? Might we read The Flight to Lucifer not as a weak rewriting of Lindsay, but rather as a failed struggle against Lewis?

Bloom’s novel does have notable elements in common with two of Lewis’s books. One is the children’s fantasy The Silver Chair, not least because both Bloom and Lewis draw on Spenser’s Elizabethan epic The Faerie Queene. Bloom even has Perscors quote a line from the poem—from an episode that includes a silver chair. Both Bloom’s and Lewis’s adventures feature sunless underworlds, heroes who struggle to recall who they really are, and seductive villainesses who dress in green.

The more telling juxtaposition, though, is with Lewis’s Perelandra. In Perelandra, the second book in Lewis’s Space Trilogy, the protagonist Elwin Ransom travels to another planet at a point in its history that corresponds to the Fall of Man in our own. At the behest of angelic “Archons,” Ransom tries to stop Satan’s attempt to corrupt Perelandra’s Adam and Eve. Lewis’s rewriting of Genesis is audacious, but presumably not “Promethian” enough for Bloom’s taste, since it accepts rather than rejects the premises of Christian theology even as it asks how that theology might play out on another world.

In The Flight to Lucifer, Bloom also attempts a kind of rewriting of Genesis. His planet features versions of the biblical flood, the tower of Babel, and Nimrod the hunter but with the familiar Gnostic twist: the biblical God is actually a satanic demiurge, and the characters who defy his authority are emissaries of truth. Unfortunately, in Bloom’s hands, these Gnostic inversions are repetitive and dramatically sterile. His characters wander around expressing defiance of the powers that be (“Perscors decided that his quest now had a clear aim: to battle against the Archons, though it be in no cause and to no purpose”) and avowing that religion is a lie of the demiurge. Bloom’s Valentinus announces:

I saw that the Gnosis alone was sufficient for salvation and freedom, and I cast out the sacraments and rituals of the Great Church’s mysteries. . . . Through knowledge, then, the inner man, the pneuma, is saved, so that to us the knowledge of original being suffices; this is our freedom; this is the true salvation.

Judaism does not come out much better than Christianity, by the way, at least if Bloom’s portrait of Lucifer’s Mandaeans, “this fearful, narrow, aggressive remnant of a people” consumed with “the common quarrel about possession of land,” means what I think it does.

All in all, The Flight to Lucifer is less of an homage to Lindsay than an anti-Perelandra. And yet, despite Bloom’s intentions, it demonstrates that what Bloom calls “Promethianism” is, well, kind of narcissistic. It turns out that Gnostic rebellion is not especially interesting, at least in Bloom’s dramatization; it seems rather adolescent and self-obsessed.

One is reminded of another C. S. Lewis-hater, Philip Pullman, whose far more impressive Dark Materials trilogy began with such promise but, hampered by its dogmatic materialism and smug insistence on the stupidity of organized religion, petered out weakly with the main characters weeping for joy over the survival of their atoms. Bloom’s fantasy lacks even Pullman’s moments of Blakean wildness, but neither Bloom nor Pullman achieve the genuine surprise afforded by Lewis’s supposedly orthodox, yet truly wild, vision.

Bloom’s introduction to his Chelsea House Modern Critical Views volume on Lewis begins, “C. S. Lewis was the most dogmatic and aggressive person I have ever met.” The essay continues with an unintentionally self-parodic account of Bloom’s interactions with Lewis in the mid-1950s when he was on a Fulbright scholarship at Cambridge:

I attended a few of his lectures, and for a while regularly talked with him at two pubs on the river. As I was twenty-four, and he fifty-six and immensely learned, I attempted to listen while saying as little as possible. But he was a Christian polemicist and I an eccentric Gnostic Jew, devoted to William Blake. We shared a love for Shelley, upon whom I was writing a Yale doctoral dissertation, and yet we meant different things by “Shelley.” Cowed as I was, the inevitable break came after a month or so, and we ceased to speak.

Bloom’s retrojected memory inflates the merest of interactions into something like the Great Bloom-Lewis Schism of 1954. “We ceased to speak”?

Moreover, Bloom does not, in this essay on Lewis, discuss any of Lewis’s books—though he does tell us, “I own and have read some two dozen of them.” He refers dismissively in passing to the Narnia Chronicles and Mere Christianity, while allowing the scholarly worth of Lewis’s celebrated study of medieval cosmology, The Discarded Image. Wholly unmentioned are The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, A Grief Observed, Miracles, The Allegory of Love, That Hideous Strength, The Abolition of Man, Till We Have Faces, and—of course—Perelandra, to name a few. Instead, we get the following:

C. S. Lewis, though as sedentary as myself, was a muscular Christian who is now the intellectual sage of George W. Bush’s America, whose Christianity is mere enough to encompass enlightened selfishness, theocratic militarism, and semi-literacy. (President George W. Bush vaunts that he never read a book through, even as a Yale undergraduate.) That a major Renaissance scholar, C. S. Lewis, should now be a hero to millions of Americans who scarcely can read is a merely social irony. Like Tolkien and Charles Williams, his good friends, Lewis is most famous for his fantasy-fiction, particularly The Chronicles of Narnia. I have just attempted to reread that tendentious evangelical taletelling, but failed. This may be because I am seventy-five, but then I can’t reread Tolkien or Williams either.

And so forth. Bloom concludes this splenetic belch with a final judgment: “Lewis was religious, which is not in itself an achievement.”

Given this evident frustration and envy, it would seem that C. S. Lewis was Bloom’s demiurge, the Crystalman he sought to defeat and displace. As his failed attempt at a fantasy novel shows, he was not successful. But then, being heretical is not in itself an achievement.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Inklings

Leo Strauss may be as devastating as C. S. Lewis in his criticism of facile and destructive dogmas, but Hollywood isn’t planning a film version of Strauss’s Natural Right and History any time soon.

Why There Is No Jewish Narnia

So why don’t Jews write more fantasy literature? And a different, deeper but related question: why are there no works of modern fantasy that are profoundly Jewish in the way that, say, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is Christian?

Talmuds and Dragons

Like the medieval literature to which it pays homage, The Inquisitor’s Tale weaves in supernatural events and divine interventions, mythic beasts and wild peoples, and even entrées into medieval theology, all liberally peppered with puns and potty humor.

Out-of-Body Experiences: Recent Israeli Science Fiction and Fantasy

The Yarkon is as good a site as any for pondering the relationship between Israel and the imagination.

Janet Brennan Croft

Bloom's introductions to his Tolkien volumes are also masterpieces of "I really don't like this guy's writing, but for some reason some of you do, so here, have a book." You might find interesting a couple of related articles that were published in Mythlore:

Schmidt, Thomas (2016) "Literary Dependence in the Fiction of C.S. Lewis: Two Case Studies," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 35 : No. 1 , Article 7.

Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol35/iss1/7 Source-hunters on C.S. Lewis must deal with what James Como called his “alchemical imagination”—his tendency to act like medieval writers who “were in the business not of inventing new material but of transforming existing material.” Schmidt tabulates parallels in Lewis’s writing to two particular sources: David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus, which Lewis acknowledged as a major influence, and V.A. Thisted’s Letters From Hell, which he claimed to his friend Arthur Greeves he couldn’t get through and gave away after trying to read only once.

Gray, William (2007) "Pullman, Lewis, MacDonald, and the Anxiety of Influence," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 25 : No. 3 , Article 11.

Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol25/iss3/11 Building on the theoretical framework of Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Influence, traces a path of influence and “anxiety” from George MacDonald through C.S. Lewis to Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy.

John

Well spotted. Peripherally... I wouldn't have let Pullman off so easily. The series starts bad and... well, I can't say because I'm not masochistic enough to finish. Never read dialogue from such puppet-like characters in my life. Unreadable. 70% of the dialogue an attempt to explain the pretentious pseudo-scientific plot. [Worth noting a concern common to the Inklings: the freedom of the reader from the author's authorial grip. Reading the words of characters that exist only to serve the author's plot is like watching the prisoners ahead of you march to the guillotine.]

Joanne Tenenbaum

A hallmark of a great work of fiction is its ability to go beyond its philosophical premise in the service of telling a compelling story. Lewis's fiction does this. Bloom's does not. Which is to say that Lewis, also a fine prose writer, achieves literature while Bloom does not. As an English major many years ago, I spent a lot of time with Lewis's histories of English Literature, which taught me more about prose writing than almost anything else I read.

The Chronicles of Narnia are a fabulous saga, Christianity notwithstanding. Put simply, for Lewis, the story was the thing. Bloom, alas, was captivated only by his own tendentious opinions.