Free Radicals

The history of American anarchists, and of Jewish anarchists in particular, has been forgotten, largely overshadowed by the history of the more well known (and far less defensible) American communist movement. Two recent books—neither of them is a conventional biography—reintroduce us to two fascinating 20th-century Jewish anarchists. The volumes are almost as quirky and unconventional as their subjects. The J. Abrams Book: The Life and Work of an Exceptional Personality is a kind of scrapbook-memoir published by friends and coworkers of the subject after his death in 1953; Left of the Left: My Memories of Sam Dolgoff is by the subject’s son Anatole, who keeps up a running dialogue with his long-dead father.

The J. Abrams Book contains fragments of the subject’s autobiography. The most compelling is his account of the five years he spent in the Soviet Union, which takes up half of the book. Surprisingly, nothing that Jacob (“Jack”) Abrams put in writing deals directly with the famous Supreme Court case that bears his name: Abrams v. United States. It’s the free speech case with which every law school graduate must be at least vaguely familiar, without necessarily remembering anything about the man it immortalized.

In July 1918, when the United States sent 15,000 troops to intervene in revolutionary Russia, Jack Abrams and some of his fellow anarchists organized a protest. They rented a six-room apartment in East Harlem as their headquarters and installed a printing press in the basement, where they produced two leaflets, one written in English and the other in Yiddish, to be distributed on New York City’s Lower East Side. “Workers,” it proclaimed, “our reply to barbaric intervention has to be a general strike! An open challenge only will let the government know that not only the Russian Worker fights for freedom, but also here in America lives the spirit of Revolution. . . . We must not and will not betray the splendid fighters of Russia.”

On August 22, 1918, they dropped five thousand of these leaflets from a tenement rooftop on the Lower East Side. They were quickly arrested and charged with conspiracy “to unlawfully utter, print, write and publish . . . disloyal, scurrilous, and abusive language about the form of government of the United States . . . language intended to incite, provoke, and encourage resistance to the United States in the war with Germany.” The trial was held in October, in an atmosphere permeated by patriotic bond drives and Liberty Loan rallies. Judge Henry DeLamar Clayton Jr., a former senator, betrayed his feelings during a cross-examination of Abrams. Speaking in a soft voice with a Yiddish accent, Abrams tried his best to defend what he meant by his anarchist beliefs: “This government was built on a revolution. When our forefathers of the American Revolution . . .”—which was as far as he managed to get. “Your what?” Judge Clayton asked. The jurors got his point. Two weeks later the defendants were found guilty. Three of them, Abrams, Samuel Lipman, and Hyman Lachowsky, were given the maximum sentence of 20 years in prison. The fourth, Mollie Steimer, received 15 years, probably because she was a young woman.

The defendants appealed the case, which went to the Supreme Court and was filed as Abrams v. United States. The majority of the court affirmed the sentence, but it led to one of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.’s most famous dissents (in which Justice Louis Brandeis joined him). Holmes’s argument that only the “clear and present danger” of immediate evil could justify restricting speech was a milestone in the defense of freedom of speech.

Abrams and his fellow defendants spent two years in jail while their attorney Harry Weinberger worked out a deal: The defendants would be released with the stipulation that they leave for Russia—their birthplace—at their own expense and never return to the United States. On November 24, 1921, Abrams, his wife Mary, and his fellow defendants set sail for the USSR.

While there are scores of books on the history of American communism, students of American politics tend to forget that, as the historian Kenyon Zimmer pointed out in his book Immigrants Against the State, anarchists once outnumbered Marxists, and by 1910 there were a few hundred thousand of them in this country. Indeed, up to World War II, Zimmer wrote, they “remained a significant—though largely forgotten—element of the American Left.” Unlike today’s masked rock-throwers, they stood for the creation of a peaceful, stateless, antiauthoritarian society where people would freely join together to govern themselves. In America, anarchist groups were largely organized by their members’ countries of origin: German, Italian, Spanish, and so on. However, it was Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who settled in New York City that became the movement’s most influential and enthusiastic adherents.

Many immigrants from poor working-class families, sent out to work at an early age and afforded only a limited education, were drawn to anarcho-syndicalism, which held out the promise that revolutionary industrial unionism would ultimately result in the workers’ control of the economy and transform society into an anarchist utopia. Jewish anarchists pursued their arguments in New York’s lively radical Yiddish-language subculture. Although they were not ashamed of their Jewish heritage, as atheists they rejected Judaism and famously held an annual Yom Kippur Ball, mocking the holiest day on the Jewish calendar.

The J. Abrams Book contains Abrams’s account of his childhood in Russia, where he was born in 1886, and continues with his arrival in the United States in 1908; his deportation back to what had become the Soviet Union in 1921; his flight from the Soviet Union five years later; and his arrival in Mexico, where he spent the last 30 years of his life.

To call his childhood painful is an understatement. After his mother died when he was four and his stepmother rejected him, he had to sleep on the floor between doorways, was often hungry, and dressed in ragged hand-me-downs. His older sister Manya took care of him, and eventually apprenticed him to a bookbinder and printer whose workers introduced him to the revolutionary antitsarist underground. Manya left for America in 1906 and sent for Jack two years later. He settled on the Lower East Side, got a job as a bookbinder, joined the International Brotherhood of Bookbinders, and was elected president of the local. His future wife, Mary Domsky, was active in the Amalgamated Clothing Workers union (she narrowly escaped dying in the tragic and famous Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire). Abrams had met her before the fire on picket lines and at forums where they heard talks by Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, and other anarchists. Abrams, who was already a revolutionary but not yet an anarchist, was persuaded.

A decade later, he was back in Russia and even more miserable than he had been as a child. After his first experiences with the Cheka, the early Soviet secret police, “it became clearer” to Abrams “that the people in America who had criticized the leadership of Soviet Russia were not completely wrong.” Indeed, everything was the opposite of what he had expected. He and Mary were assigned to one small room with three other people, hunger was endemic, people were dressed in rags, and the Bolshevik claim to have eliminated prostitution was patently false. At the time, the Bolsheviks were trying to destroy those with other radical tendencies, including socialists and anarchists who had fought alongside them to overthrow the tsar, but Abrams had defended the revolution and had paid for it. He was informed that his status was that of a “non-party member with a Soviet lining,” but, as he soon found out, it did not protect him from Soviet repression. When he spoke up at meetings he was admonished and told “the collective is the boss and the individual is his servant.”

When asked what kind of work he would like to do, he suggested that he set up and run an automatic laundry, which he had learned how to do in prison. He was immediately given permission to set up the first modern laundry in Russia, which operated out of the basement of the Foreign Ministry. However, when he protested inefficiencies and graft he was ignored, and eventually charges of anti-Soviet activity were brought against him. Disenchanted, he concluded that it was time to “abandon this land of one’s hopes.”

Realizing that if he and Mary wanted to leave he would have to find employment in an enterprise that was not run directly by the Soviet state, he quit his job. Since their housing was tied to government employment, they were immediately evicted. They had to live in the corridor for six weeks, until a friend took them into his apartment, which was meant for one person but now housed six. As it happened, two of the spaces were taken by political tourists, Ronald Radosh’s parents. Abrams asked if when they returned to New York, they would tell the truth about how people really lived in the workers’ paradise. Reuben Radosh told him that he would not, since he had to defend the idea of the Soviet revolution, not depict its reality, to which Abrams responded, “happy is the believer, for whom even bad things become transformed into good ones.” In 1926, Abrams told the commissars that he and Mary would be of more value to the revolution in other countries, a fable he told them in the hope he would get official permission to leave. Much to his surprise, after an interrogation at the infamous Lubyanka prison, he and Mary received two passports. They gladly left Russia for good (albeit with the GPU on their trail). Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman had earlier learned a similar lesson during their Russian exile. Like the proverbial canaries in a coal mine, the American anarchists became the first critics on the Left to expose the horrors of Bolshevism.

The next year, Abrams and Mary arrived in Mexico, where the National Revolutionary Party had come to power. There weren’t many anarchists in Mexico, but they were welcomed by the small but growing Jewish community. “In Jewish Mexico,” one of his friends wrote in tribute, “it was the community activists of the younger [Jewish] generation who were his audiences and his adherents.” Eventually Abrams became a director of the Jewish Cultural Center. He found work as a photographer and then set up a printing shop where he printed Yiddish books and newspapers. He also chaired Mexico’s International Committee Against Fascism, which supported the Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. When refugees began arriving after Franco’s victory, Abrams organized to help them and other antifascist exiles.

In 1937, Leon Trotsky arrived in Mexico. Knowing that he was short of funds, his host, the then- Trotskyist painter Diego Rivera, introduced him to Abrams, who was able to arrange a loan. The two became unlikely friends, and Abrams often visited him at his home in Coyoacán just outside of Mexico City. On one occasion, when they were having lunch, Trotsky began denouncing Stalin and his other foes. Abrams, who always spoke his mind, responded:

I’m only fifty-percent in agreement with you. I agree with what you say about your former comrades when you condemn them. However, here’s where we part ways. I don’t agree that if you were in Stalin’s place, you would be better. Dictatorship has its own logic; perhaps you would be even worse.

When Trotsky told him that he took pride in his order to have the Red Army put down the attempted rebellion of the Kronstadt sailors during the civil war Abrams condemned him to which Trotsky responded, “I would have done the same if it took place now,” thereby verifying Abrams’ critique.

A friend in the Jewish community later commented, after witnessing this exchange, that “not everyone could do this,” and yet Abrams did and remained “good friends with Trotsky.”

In 1945 Abrams was diagnosed with throat cancer. Through the intercession of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, he was allowed to seek medical care in the United States, where he was guarded by a federal marshal day and night. After several treatments at Temple University’s hospital Jacob Abrams died in Mexico in 1953. Mary, who did not want a religious service, wrote the inscription for his tombstone: “J. Abrams who fought passionately for freedom, justice and tolerance.”

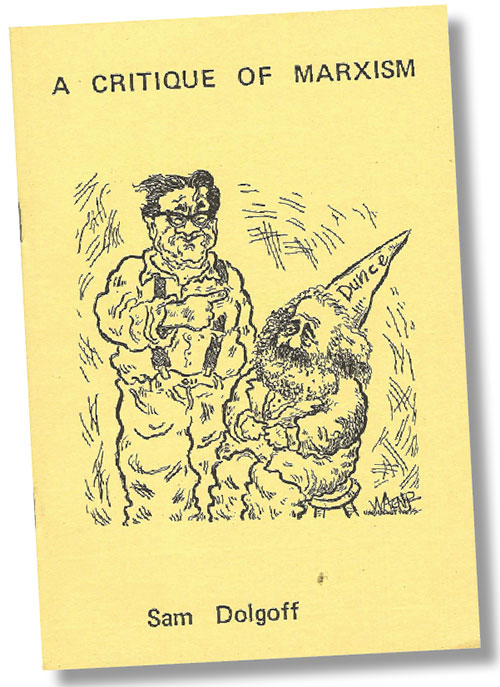

In Left of the Left: My Memories of Sam Dolgoff, Anatole Dolgoff sets out to tell not only his family’s story but also “the history of a culture, and of a chapter of American radicalism that few people know about.” Dolgoff strives to give an emotionally honest and impartial look at his parents and himself, warts and all, although he seems to be harder on himself. Looking back, he writes that except for his parents, “I doubt there is much to my life you would find interesting.” His academic career at the New York City College of Technology teaching physics paled in comparison. At the end of his career, he found that his father was more and more on his mind, and students complained that “I talk about my parents too much, proof to them that I am over the hill and growing senile.” He was neither and wrote the book after he retired.

Sam Dolgoff belonged to a slightly later generation of Jewish anarchists than Jack Abrams. His father, Max, had been a rebel back in Russia, where he enraged his own rabbi father “by renouncing religion altogether.” When Max was about to be conscripted into the army, he left for America and in 1905 sent for his wife Anna and their three-year-old son Sam. Sam was a socialist by the age of 14, but he soon concluded that the socialists were mere reformers who were not really interested in uprooting the capitalist system or transforming society. When he started expressing these views at meetings and publishing his ideas in a mimeographed paper he called Friends of Freedom, he was put on trial and expelled from the Socialist Party for insubordination. Afterwards, one of the party judges came up to him and said, “I am going to give you a tip. You are not a socialist. You are an anarchist.” Dolgoff promptly asked him for an address. When he made his way to a dingy loft near Union Square, the anarchists welcomed him with open arms, but he was soon dissatisfied with what felt more like a debating society for misfits than a political movement. One member told him that he “was not a Road to Freedom type. ‘You are an anarcho-syndicalist. You are an IWW, a Wobbly!’”

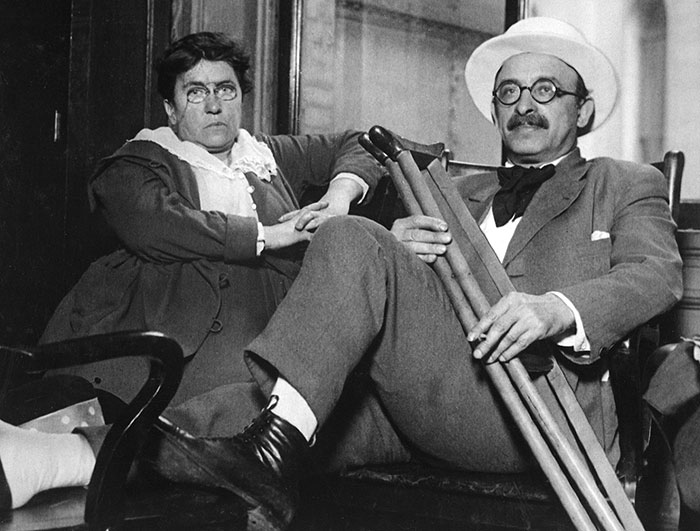

He joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1922 and became a migratory worker riding the rails, propagating anarcho-syndicalist ideas, and participating in strikes. On a trip to Cleveland he met Esther Miller, a delegate from the Anarchist Forum who had agreed to meet a speaker from the IWW on the steps of the library. After an hour of waiting, she started to leave when she looked more closely at a hobo who had been pacing back and forth there for the whole time. Of course, it was Sam. Anatole Dolgoff describes his father during this period as having “a strong face, a rugged Russian Jewish face, wild black hair swept back, acute black eyes behind the glasses, a prominent nose,” and he quotes an acquaintance as saying that Sam looked like he combed his hair with an eggbeater. Esther, by contrast, was a “proper young lady from a striving, high-achieving, first-generation immigrant family—well mannered, well spoken, and immaculately dressed” who had earned an MA in English literature. Her family thought it was perverse of her to “run off with a Wobbly, a filthy hobo house painter,” but they were married for 58 years.

In 1933, Sam and Esther moved to Stelton, New Jersey, a “largely anarchistic colony,” but concluded that such places were “essentially self-isolationist forms of escapism.” They settled in New York City where Sam, together with Carlo Tresca and his circle of Italian anarchists, helped found the Vanguard Group, an anarcho-communist group that largely propagated “the ideas of Bakunin and Kropotkin.” Sam edited and wrote a column for its publication, Vanguard: A Libertarian Communist Journal, focusing on the American labor movement.

But a cause that consumed his time and energy, as it did in Mexico for Abrams, was the Spanish Revolution, during which anarchists had temporarily established a functioning anarchist society in northeast Spain, including Barcelona, until the cause was defeated by the Communists. Dolgoff was ready to join the fight but was told that what the anarchists needed more than anything was not fighters but arms, money, and international support. Looking back on it Dolgoff wrote that “about eight million people directly or indirectly participated” in the Spanish Revolution, which “came closer to realizing the ideal of the free stateless society on a vast scale than any other revolution in history.”

In 1954, he and others formed the Libertarian League, which held forums every Friday night featuring nonanarchist speakers such as Michael Harrington, Bayard Rustin, and Dorothy Day. Dolgoff also developed relationships with Paul Goodman and Dave Van Ronk, the sometimes Trotskyist/anarchist blues and folk singer who regarded him as a mentor and surrogate father figure. When the 1960s arrived, Sam and Esther found the behavior of what might be called “lifestyle” anarchists infuriating. “I am sick and tired,” Sam told Paul Avrich, the foremost historian of the anarchist movement, “of these half-assed artists and poets who reject organization and want only to play with their belly buttons.” But he was not ready to give up on them and mentored such figures as Tuli Kupferberg of the Fugs, a counterculture folk-rock band. What upset Dolgoff the most was the young radicals’ embrace of Fidel Castro, whom he quickly recognized as a Stalinist dictator. He campaigned on behalf of the Cuban anarchists whom Castro had attacked and exiled, and waged a 15-year battle against the pro-Castro Left. In 1976, he published The Cuban Revolution: A Critical Perspective. The critic Paul Berman has best summed up what Dolgoff meant to so many:

Sam Dolgoff had many great traits, but the greatest of all was a nobility of character—a human sympathy that made him side with the downtrodden . . . He taught me how to look at the world through eyes that are not the same as the official eyes of the state and the big establishment and the ideologues.

As the child of anarchists, Anatole Dolgoff has developed an untraditional and rather disorganized format to present the story of his father. He tells us that during his childhood there were two Anatoles: the one who lived in his parents’ world of radical ideologues and lost causes, which he kept secret and was often embarrassed by, and the one who lived on the streets and at school with his friends. Then there was his father’s alcoholism, which almost destroyed the family. While Anatole’s love for his parents is apparent, the process of writing his book clearly helped him to accept and admire them. He does not, however, let his father off the hook on several issues. For example, Sam criticized Emma Goldman for not being “very enthusiastic about the IWW” and for “not really asking for much more than what today would be considered a liberal program.” His son disagrees, writing, “Emma and her group supported the Wobblies and the class struggle ‘a-plenty,’ in my opinion.” While Sam was infuriated by the pro-Castro Left, his son takes a more charitable view of them, writing: “Clearly they were mistaken. But their mistakes were motivated by enthusiasm for what they thought was a genuine revolution of the poor and downtrodden. They fell in love and love can be blind.”

Jack Abrams and Sam Dolgoff shared more than their identities as anarcho-syndicalists. They were both idealistic, courageous, single-minded, and passionate in fighting for their cause and for freedom not only in America but internationally. Like many of their fellow Jewish immigrants they were self-taught and eager to learn; they were working-class intellectuals and charismatic orators—a lost Jewish type. They were also fortunate to marry women (who in anarchist fashion were referred to as “life companions”) who were devoted to their shared cause.

What then did these Jewish anarchists accomplish? After all, they not only failed to achieve their lifelong dream of a free cooperative society without a state to rule over them; they failed to attract enough believers in that dream to keep the movement alive. Perhaps their biggest mistake was the belief that humankind was basically good despite all they had experienced to the contrary. On the other hand, they were clear-eyed, even prophetic, in their early disillusionment with communism. They were dreamers, but their dream was a noble one and worthy of being remembered.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Weaver

An-sky's photographs.

Three Portraits of Jewish Excellence—at 29

At the age of 29, David Ben-Gurion was speaking to empty halls across America for the Zionist movement and Leo Strauss was finding the “theological-political predicament” insoluble. As for Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, he was in Berlin worrying about epistemology and halakha. Three portraits of Jewish excellence in the making.

The Romance and Rage of Rashbi

In the technical halakhic sense, Lag BaOmer is not really a festival, and it is not attested to in any of the classical sources. So how did the Hilula de-Rashbi, as the Meron Lag BaOmer celebration is called, become such a large, and largely Hasidic, pilgrimage—and rave?

State or Substate?

“Nonstatist” Zionists, as the historian David Myers has dubbed them, have received a lot of attention in recent years. Dmitry Shumsky, a historian at the Hebrew University, is grateful for this scholarship but believes that it has not gone far enough.

CANTOR ROBERT COHEN

I found this review both funny and side, highly imaginative and informative as well. I knew the name "Sam Dolgoff" (I am also a good friend of Ron & Allis Radosh), but not Jack Abrams. Their stories, as retold in this review, are amazing. As some one who grew up in a fellow traveling family (friends of Communists), we did not think about, talk about or consider the existence of anarchists. I am aware, as I know Ron & Allis are, of some of the violent groups of anarchists and their violent actions that killed some people. Sam & Jack don't seem to be of that inclination - I wonder if they write about though.

Also as a Cantor in a synagogue (although growing up an aetheist) I wonder how much Jack and Sam realized their concern for human rights, for the poor, for democratic decency, was founded in Judaism, in the religion which was the first to speak of loving your brother as yourself and for caring for the stranger. In their own anti-religious ways, they were rabbis (teachers) to many who worked and are working for a better world, who know (unlike them as the Radoshes describe) that humans are (far from) perfect, containing the Yetzer Harah and the Yetzer Tov, feelings of good and evil, but there is still hope, despite today's horrible leadership of our country, for a better world.

Thanks for printing this great review. Cantor Bob Cohen