Romania!

The first time I ever heard of Romania was not as a country, but as a song—the famous, perhaps infamous, or perhaps now completely forgotten by anyone under 60, campy Yiddish classic whose signature lyric is an endlessly and lovingly repeated “Romania!” I first heard it at the age of 10 at my suburban New Jersey synagogue, where my parents brought me to hear a singer whose outsized performance of this song still haunts and baffles me. A kind of aria hijacked by a comedy routine, “Romania” is a show in itself, over six minutes long and all about the manic energy of the performer, fueled by a kind of parody of nostalgia.

The ridiculously chipper song was created by the Yiddish virtuoso Aaron Lebedev in 1947, not long after the murders of nearly half a million Romanian Jews, and begins as follows:

Ah, Romania, Romania, Romania, Romania, Romania—

The former Romania, not the current Romania,

The good Romania, Romania, Romania, was once, once, once, once—not today—

A sweet, good, beautiful land . . .

The rest of the lyrics about this sweet, good, beautiful land—where several anti-Semitic political parties preyed on Jews in the decades before the Holocaust—are about food, girls, and food.

I could not make this up, but someone did—and in my New Jersey shul, the singer took it to such extremes that, in the overblown ecstasies of the song, he literally rolled around on the floor. The crowd, mostly my grandparents’ age, ate it up. My siblings and I watched with a deep discomfort that we hid behind stupid jokes. Many years later, it occurred to me that what we were watching in 1987 had nothing at all to do with Romania and almost nothing to do with Romanian Jews. It wasn’t even nostalgia, but rather a reenactment of nostalgia: a painfully failed attempt to fill an enormous void.

People have been making things up about Romania for a long time, expressing an otherwise unspoken insecurity, guilt, or mortal terror. This applies not only to Dracula author Bram Stoker and Yiddish playwrights but also to the various regimes that have ruled the real Romania over the past century—each of which has invented its own self-serving and lie-laced version of the country’s past.

It has been many years since I felt that profound discomfort of hearing “Romania.” But I felt it again as I returned, in art, to Romania, this time to the current Romania, which is apparently not very sweet or good or beautiful at all. As I watched “I Do Not Care if We Go Down in History as Barbarians,” the new, bizarre, powerful, and devastating film by the renowned Romanian filmmaker Radu Jude, I once more experienced the bafflement and pain of watching someone trying to cover up a black hole.

Like “Romania,” “I Do Not Care if We Go Down in History as Barbarians” is a reenactment; the quotation marks are part of its title, suggesting just how meta this film becomes. It steps back one more level into the minds of the people doing the reenacting. And what it is trying to reenact is not life, but death—specifically, the mass murders, by Romanians, of thousands upon thousands of Jews.

“I Do Not Care . . .” is a kind of mockumentary, a fictional film about the making of a show within a show. Mariana (mesmerizingly played by Ioana Iacob) is a young director putting on a pageant commemorating a supposedly heroic moment in Romania’s history, the Romanian victory over the Red Army in Odessa in 1941. The municipal government funding her pageant is hoping for a display of nationalist glory, which is how post-Communist Romanians now view the conquest of Odessa. But Mariana has something different in mind. She wants to reenact another aspect of the Odessa victory: the murder of some 20,000 of Odessa’s Jews, which was in fact only two days out of a years-long, Romanian-led campaign of mass murder. She is convinced that if today’s Romanians knew what their countrymen did, the country could move beyond mindless patriotism to a mature and vibrant future. To no one’s surprise but hers, that isn’t in the cards.

The popular canonization of Antonescu is particularly galling to Mariana because he and the Romanian army, with the gleeful help of Romanian civilians, were personally responsible for the murders of tens of thousands of Jews aside from those they helped deport to Nazi camps. The slaughter included not only mass shootings but also public hangings and Jews being burned alive, often after bouts of rape and torture—all independent of the Nazis. In fact, according to historian Raul Hilberg, after Nazi Germany, Romania has the distinction of murdering the largest number of Jews; Adolf Eichmann was apparently angry with Antonescu for killing Jews faster than anyone could bury them. The film’s title is a quote from Antonescu, describing the need to “clear the land” of Jews regardless of the verdict of history. When Mariana’s extremely amateur cast gets wind of what she’s up to, they castigate her, shouting, “Antonescu is a saint!” By the film’s chilling end, we discover just how much Romanians regard him as a saint—not those in the former Romania, but the current Romania, Romania, Romania—and also exactly why.

The power of “I Do Not Care . . .” lies in its form, which is unsettling in the extreme. On its surface, it is a dark comedy about the absurdities of reenacting the past—as Mariana puts it while labeling one bearded extra “Karl Marx”—“first as tragedy, then as farce.” Like that performance of “Romania” I watched long ago, the farce here is turned up all the way to 11. In one early scene, Mariana rifles through costume racks of Nazi uniforms which, a warehouse employee informs her, were last used in an American film entitled Zombies versus Wehrmacht. “It all has to be authentic,” Mariana insists, examining the Iron Crosses. During this conversation, a man walks in dressed as a polar bear and asks where he can change.

These mordant moments become increasingly uncomfortable as the film progresses.In one noncostumed rehearsal, awkward actors point their guns at “Jews” in Hawaiian shirts and baseball caps; Mariana tells the children among them to “raise your hands like that kid in the Warsaw ghetto.” The Hawaiian shirts are laughable until one remembers that the Jews who were murdered were also not wearing costumes; they were forced to the ground and shot in 1940s streetwear, made picturesque and costume-like only by the many films we have seen of them. Later, some actors start complaining about their Roma colleagues, insisting (with zero irony) that “We won’t mingle with Gypsies!”

The more discomfiting moments come when Mariana lingers in some extremely intimate setting—in her underwear, in the bathtub, on Skype, in bed with her lover (played by Serban Pavlu)—and simply reads aloud from historical accounts of massacres of Jews. Sometimes the camera lingers, as if accidentally, on a horrific archival image while the film’s actual actors discuss something tangentially related, or unrelated, or walk away. Many moments in this film consist of endless still shots of, say, a long row of bodies of massacred Jews lying in a heap against a wall, the camera lingering long after the scene has ended. The effect is not subtle. Like the repeated “Romanias” of the song, the murders do not go away.

The plot of “I Do Not Care . . .” essentially consists of Mariana banging her head against an invisible wall of opposition. Her chief antagonists are two pompous older men whose mansplaining would be hilarious if it weren’t so painfully realistic. The first is her lover, a married pilot who complains that “I’m sick of all the Jews whining” and who eventually reveals that by “whining” he means “requesting accountability”—accountability being entirely alien to him, particularly when Mariana becomes pregnant.

The second and more significant antagonist is Movila (played by Alexandru Dabija), a fake-friendly representative of the government’s arts commission who threatens to pull Mariana’s funding if she so much as suggests Romanian responsibility for slaughtering Jews. Mariana’s maddening arguments with Movila will feel viscerally familiar to anyone who has ever, say, tried to defend Israel on Twitter.

Movila’s first tactic is to accuse Mariana of being anti-Romanian for not emphasizing the Soviet defeat, but he soon moves on to minimizing Romanian crimes: “380,000 [murdered Jews]? Isn’t it a bit much? Maybe you miscounted them? Or counted them twice?” When Mariana documents every claim, Movila advances to relativism: “What is truth, anyway? . . . Every historian is just copying from other historians.” After that, he goes for aesthetics: Reenacting a massacre, he patronizingly tells her, is “in poor taste.” Finally, he graduates to whataboutism: “Why not do a show about ISIS? Or about massacres in Namibia?” Mariana stands her ground, but his belittling of her is capped off in a brilliantly repellant move that says it all: He asks for her number, and then ostentatiously writes it on his arm like a concentration-camp tattoo.

I’m going to go ahead and tell you how Mariana’s pageant comes off, because that’s the only way to convey why this movie is so devastating—and also because, if you have been Jewish and conscious during any of the last 10 or 15 years, it’s not going to surprise you, though it apparently stunned many reviewers who felt the need not to ruin the shocking, shocking surprise. So, spoiler alert: People still hate Jews.

Flouting both her nemeses and her cast, Mariana puts on her unedited pageant in front of a large crowd, including the city’s deputy mayor. The crowd cheers as the Romanian army actors enter, then quiets down as the troops assemble for a pep talk from a priest. “Never forget: You serve the Romanian nation,” the priest proclaims and then continues, in what ought to be a non sequitur, “Dirty Jews must be crushed!” Warming to his theme, he continues by quoting celebrated Romanian poets, scientists, and intellectuals saying things like: “Dirty Jews crush our pride / How long shall we abide?” . . . “Drown them all in the Danube; let’s extinguish their race!” . . . “Couldn’t we exterminate them like cockroaches?” . . . “Jews must be shown no mercy, or they will crush us!” and “Let everyone know: we fight not the Slavs but the Jews, to the death!” At each line, the cheers of the 2019 crowd escalate.

Once the Red Army is routed in a campy battle scene, the “Jews”—now clothed in 1940s streetwear—are herded in and forced to the ground at gunpoint. Painfully caricatured hijinks ensue: A soldier tears a Torah scroll away from a bearded “Jew”; another “Jew” tries to buy his way out; a third “Jew” escapes into the crowd of pageant-goers, who gleefully return him to his place face down on the pavement. Before long, the “Jews” are stuffed into a fake wooden building that is set aflame. At this, the 2019 crowd goes wild, whooping and laughing, their phones held aloft as they document it for Instagram. Even the mayor applauds. Mariana is alone, puzzled: What she thought was the forgotten past is actually just the present, alive and burning. Then the movie ends.

At that point, comment and critique ought to end too. As the movie proclaims with a lingering silent shot of mannequins on gallows, followed by entirely silent credits, there is nothing more to say.

But there is, in fact, more to say—and it is that dark void, the one unmentioned in this film, that shook me as I watched.

At 10 years old, listening to “Romania,” I knew nothing about Romania. Now at 42, with a doctorate in Yiddish and 15 years of teaching and scholarship, I watched this movie and still thought I knew nothing about Romania. On the surface, I was right: Romanian political history, figures like Antonescu, and even the Romanian occupation of Odessa were entirely new to me. But as the film unspooled before me with its archival footage and historical references, certain place-names in current and former Romanian territory popped up again and again, and I realized, slowly and horribly, that I actually know quite a lot about Romania—not the current Romania, but the Romania, Romania, Romania of once, once, once, once, not today.

When the movie mentioned the city of Cernauti, I realized with a jolt that that was Tshernovits—the city known for the lauded Tshernovits Conference of 1908, where the great Yiddish writer Y. L. Peretz and many others declared Yiddish a national Jewish language, deserving of institutional support. Tshernovits was also the birthplace of my favorite poet, the joyous 20th-century troubadour Itsik Manger, whose brilliant poetry enacted what he called literatoyre, lighthearted secular literature emboldened and enriched by its Torah roots. When Mariana mentioned a massacre of Jews in the city of Iasi, I realized that it was the city known in Yiddish as Yos—where Avrom Goldfadn, founder of the Yiddish theater, performed his first Yiddish play in a wine garden in 1876.

As I watched the film, names like these kept seeping in unacknowledged, because no one in the film had the knowledge to do so. Here was Satu Mare—a hick town to Romanians, but known on my planet as the birthplace of the Satmar Hasidim, who in their enclaves today maintain Yiddish as a living language even as it has died out nearly everywhere else. There was Focsani—another nowhereseville from the Romanian viewpoint but cemented in my memory as the hometown of the paradigm-setting scholar Solomon Schechter. It was also the host city for the world’s first Zionist congress in 1881 (16 years before Herzl’s in Basel), which was successful enough to send a group of Focsani natives, including Schechter’s identical twin, to found the Israeli cities of Rosh Pina and Zikhron Yaakov.

Odessa is the center of the movie’s reenactment, the site of the battle with the Red Army, but I can’t think of Odessa without thinking of the foremost Yiddish novelist Mendele Mokher Seforim, who was so stunned by the 1871 Odessa pogrom that it killed his hopes for the Jewish Enlightenment and launched his writing to surreal new heights, and also of Vladimir Jabotinsky, the entirely assimilated Russian Jew who became the hardest of hardcore Zionists, convinced that there was no future for Jews in Europe. These Jews of Romania (not the current Romania, but the Romania of once, once, once, not today) were right when everyone around them was wrong, each in their own way, politically, artistically, and literarily. They stared down into that void and found truth.

For Mariana, the truth is nothing more than murder, a dark pit of sadism and slaughter at the heart of her own country’s identity. For most people who see this film, that will be disturbing enough. But I also shuddered at the profound emptiness at its core, the same terrifying emptiness I sensed when I first heard “Romania,” that parody of the past. As noble as Mariana genuinely is, she and the frightening crowd at her pageant have one thing in common. They are all only interested in dead Jews.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Radically Enlightened Jews

Jonathan Israel is a minyan of modern revolutionaries.

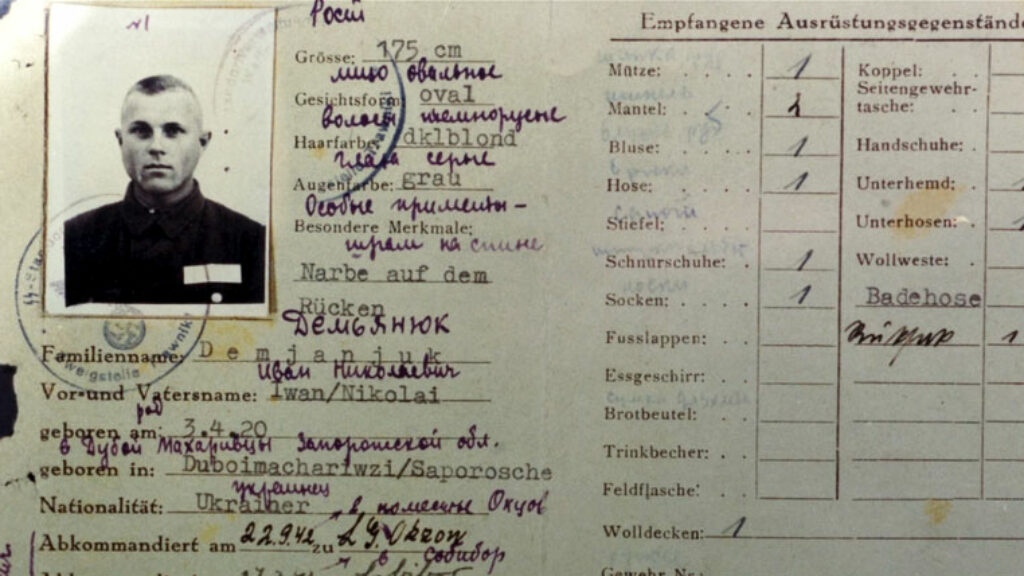

Ivan the Terrible?

A new miniseries from Netflix manages to maintain the tension of the long-decided, if not entirely resolved, case of John Demjanjuk.

What Goes Into Survival: A Report from the Washington Rally

People came by the hundreds of thousands, schlepping by train, chartered bus, overnight flight. Students raised money from relatives. Federations funded last-minute airfare. It was a rally for people who don’t attend rallies.

The Language of Tradition

On tradition as a first language.

Solon Beinfeld

I haven't seen "I Do Not Care...", but I heard Lebedeff's "Rumeynye, Rumeynye" (and saw him sing and dance it in person) as a boy long before Professor Horn saw and heard the "updated" English-language version. The song dates, in fact, from 1925. While Romanian anti-Semitism was perfectly well-known even then, the song points jokingly to the relative ease of life enjoyed by this southernmost Yiddish-speaking community. Food and wine were cheap and abundant, the climate mild compared to Poland or Lithuania and religious practice not overly strict. Yes, the Antonescu regime perpetrated unspeakable horrors on the Jews in territories annexed from the Soviet Union in World War II (Transnistria) or reclaimed from recent Soviet occupation (Bessarabia/Moldova) and Bukovina). But the Jews in Romania proper (the Regat) were mostly left alone. Several hundreds of thousands survived the war and the number would have been much higher had not Northern Transylvania (including Sziget and Satmar) been transferred to Hungary in 1942 at Hitler's insistence. In Cluj/Kolozsvar, on the Hungarian side of the new border, Jews tried to flee to Romania. Even in Transnistria, the Jewish genocide was relatively less thorough. Some Jewish shtetls, like Shargorod, uniquely retained their Jewish character and Yiddish speech long into the postwar period despite the suffering and loss of life in the Ghetto.

Genocide is genocide even when less thorough than elsewhere. I have no interest in absolving the murderer Antonescu, even if he changed sides late in the war and stopped persecuting Jews. But I believe in keeping the historical (and musical) record as straight as possible.

Amy Roth

Two of the most revered women's tennis players today are Romanian: Simona Halep, who won the French open this year and is surely one of the most gracious athletes out there; and Bianca Andreescu -- the 19-year-old who defeated Serena Williams in the finals of this year's U.S. Open tournament. Bianca plays for Canada, to which her parents moved before her birth, but I believe often returns with her family to their beloved home country, and may speak Romanian at home with her parents. Everyone who follows women's tennis admires Bianca for her skill, her never-give-up attitude, her nerves of steel and her just plain likability.

Then there's the most famous women's gymnast who ever lived: the Romanian Nadia Comaneci. What is it about this terrible country that enables them to produce such skillful and gracious female athletes???

g katz

the article fails to recognize that the film is a breakthrough in shedding light on this ignominious period of Romanian history.

Bernice Heilbrunn

Your article resonates with me. For a long time, I was perplexed by the fact that the Congress of Berlin in 1878 made such an issue of the treatment of Jews by Romania. How did we Jews manage to capture the attention of Western European governments and the great and powerful Bismarck and focus them all on the treatment of Jews by Romania? Part of the answer, as historian Fritz Stern laid it out with evidence to spare, was the terrible persecution of Jews beginning in May 1867 and continuing into the 1870s by Romania, endorsed by Russia. Although life for Jews in Romania was supposedly a step above that under the Czar, nevertheless Romania seemed impossibly cruel, sending Jews to their death, burning a synagogue in Bucharest to the ground, denying them citizenship as a matter of law and thus a right to an education. From Dara Horn's description, we learn that some attitudes appear never to change.