Happy Is the People Who Knows the Blast

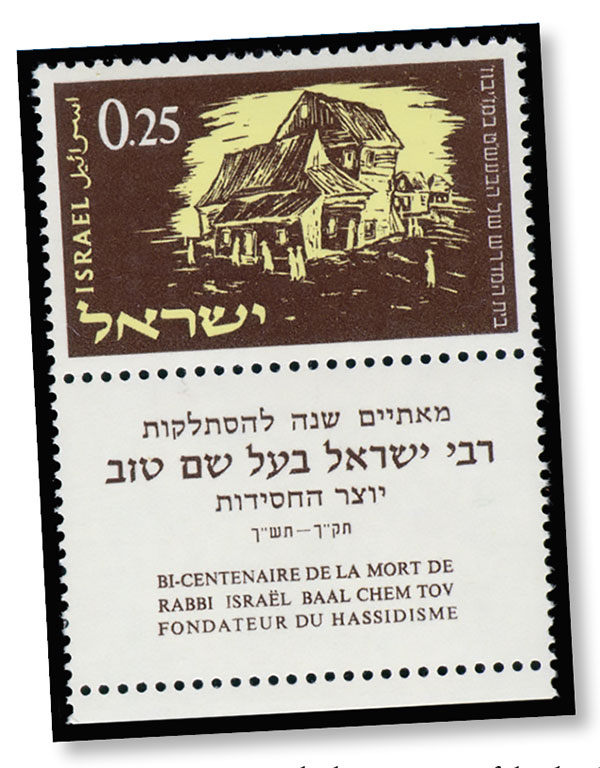

Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim of Sudilkov (ca. 1740–1800) was the grandson of Israel Ba’al Shem Tov (ca. 1700–1760), the charismatic miracle worker and mystic who is widely recognized as the founder of the Hasidic movement. His younger brother Barukh of Mezhbizh was an important early Hasidic master who established one of the first grand Hasidic courts. Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim himself led a much more modest, even ascetic, life as the preacher of Sudilkov, in Volhynia. Among his other distinguished relatives was Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, his nephew, who would become perhaps the most literarily brilliant and certainly the most idiosyncratic tzaddik among the next generation of Hasidic masters. The sermon which Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim preached at this nephew’s bar mitzvah in 1785 is said to have left a deep impression on the future tzaddik.

Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim’s book, Sefer Degel Machaneh Efrayim (translated as The Flag of the Camp of Efrayim, the title ties a biblical phrase to the name of the author in accepted rabbinic fashion), is a collection of wide-ranging sermons organized by the weekly Torah portion, many of which quote his grandfather the Ba’al Shem Tov, with whom he grew up. The book also has an appendix of other writings, most famously including accounts of the dreams the author had between 1780 and 1786 in which his grandfather visited him, taught him, and conferred authority upon him.

Sefer Degel Machaneh Efrayim was not published until 10 years after its author’s death, in 1810. Since then, it has gone through more than a dozen editions, becoming one of the most popular and influential works of Hasidic thought. In addition to being a brilliant collection of sermons, it is a key early source for the ideas and practices of the Ba’al Shem Tov and early Hasidism.

The passage translated below is taken from a sermon on the haftarah for the Torah portion of Nitzavim, which is read on the Shabbat before Rosh Hashanah. It is an inspiring and theologically bold interpretation of the religious meaning of the shofar blasts and the biblical verse read after them in synagogue. At the heart of this Hasidic teaching is a radical conception of God in which the Divine Being is held to be literally present in the ordinary objects of the material world—as being within the material “garments” and “shells” of apparently mundane things. Thus, the divine life force, by which the world is sustained, is to be found in every aspect of life, “in eating and drinking and business and the like.”

This metaphysical idea underlies the Hasidic commitment to avoda be-gashmiyut (worship through corporeality or materiality). In this conception of worship, which has recently been illuminated by the contemporary Israeli scholar Tsippi Kauffman, devotion to God must happen not only in the act of prayer or other rituals but also in the most seemingly profane of everyday activities.

Precisely because God was believed to dwell within all things, including those of this lower world, the task of the individual was to uncover the spiritual inwardness that is clothed, or hidden, by the outer garments of existence. One way in which the Hasidim were fond of illustrating this was by noting that one of the primary Hebrew words for God, Elohim, is numerically equivalent to the word for nature, ha-teva; the values of both of their constituent letters add up to 86. This radical gematria (as this practice of theological letter-counting is known) seems to suggest that if one could truly see beyond the appearance of the natural world, one would behold God.

In the section of the sermon translated below, Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim interprets a verse from Psalms, “Happy is the people [ashrei ha’am] who knows the blast [yodei terua] of God; they will walk in the light of your face” (Psalms 89:16), which is read responsively immediately after the shofar blast on both days of Rosh Hashanah. This verse is explicated with the use of several other verses from Psalms and one from Proverbs, each of which is given a characteristic kabbalistic or Hasidic twist. Although the interpretative moves are made quickly, they can be followed, even by the reader who is new to Hasidic homiletics, if the religious ideas sketched above are kept in mind. The result is the striking and still-relevant claim that the blast of the shofar on Rosh Hashanah evokes and inspires the breaking open of the human mind to the realization that the Divine Presence always resides just below the surface appearances of our world.

Thus, Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim offers a kavanah—a meaning or intention—with which to approach the sounding of the shofar and the subsequent recital of Psalms 89:16 on Rosh Hashanah. The sound of the shofar should—in a very precise theological sense—blast open the listener’s spiritual consciousness. Moreover, listening to the shofar should initiate or reinitiate an attitude of attentive wonder toward the world on the part of the Hasid, or any individual, and the way he (or she) moves through it in his (or her) daily life, trying to see the divine light within the mundane realm.

“Happy is the people (ashrei ha-am) who knows the blast (yodei terua) of God; they will walk in the light of your face” (Psalms 89:16). To explain this, we must see it according to the meaning of the verse “My soul thirsts for Elohim, for the living God, when will I approach and see the face of Elohim?” (Psalms 42:3)

For behold, in all things—such as eating and drinking and business and the like—there is within the thing an element that enlivens it (ha-mehaye oto). This is the meaning of “My soul thirsts for God” (tzama nafshi le-Elohim); [“God”] is the gematria (the numerical equivalent) of “nature.”

“For the living God”—this is the essence of [the person’s] desire for the element that gives life to the thing through nature. “When will I approach and see the face of God?”—this refers to the [divine] inwardness of Nature (penimiyut ha-teva).

Furthermore, this is the meaning of “God has ascended in the blast[of the shofar],” ala Elohim bi-terua (Psalms 47:6)— which is to say that when [the person] breaks [open] the natural world, which is the garment for the inwardness, and his mind is directed only to that inwardness, then this is [the realization and meaning of the words] ala Elohim (God ascended), that is: Nature has an ascension [or “is raised up”].

Bi-terua, “with a blast”—that is to say, when [the person] breaks [open] the natural world (ke-shemeshaber ha-teva), as was mentioned above, then God is [revealed] in the sound of the shofar.

For the inwardness of Nature is the holy blessed [four letter] Name of God (ha-shem HaVaYaH barukh hu, the Tetragrammaton), which is [a force or dimension that is] beyond the way of Nature (she-hi le-ma’alah mi derekh ha-teva). And this is the meaning of [the phrase] “God is [present] in the voice of the shofar”(Psalms 47:6).

Thus [the meaning of] “Happy is the people (ashrei ha-am) who knows the blast (yodei terua) of God” is that they know how to break [apart] the natural realm [so as to cast away the outer] garments (she-yodim leshaber ha-teva me-halevushim). Then “they will walk in the light of your face”(Psalms 89:16)—in the inner light, which is the Name of God, which is the meaning of (Proverbs 16:15): “In the light of the King’s face is life” (be-or pnei melekh hayim). Understand this.

Suggested Reading

Darkness and Light: Leonard Cohen and the New Cantors—A Playlist for the High Holidays

Old World Ashkenazi cantorial art—khazones—is making a comeback, with a surprising little boost from Leonard Cohen's new single (yes, that Leonard Cohen).

No Empty Place

The most substantial theoretical response to Hasidism from a leader of the mitnagdic—literally, opposition—movement did not appear until 1824, three years after the passing of its author, Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin.

The Rise of Hank Greenberg

On Rosh Hashana, Greenberg went to shul, then the ballpark and hit two home runs. "Hank’s Homers are strictly Kosher," said the Detroit Free Press.

At the Threshold of Forgiveness: A Study of Law and Narrative in the Talmud

In this season of repentance, it is not only the laws of the rabbis, but their stories as well, that teach us how—and how not—to forgive.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In