Hasidic Renewal on the Brink of Destruction

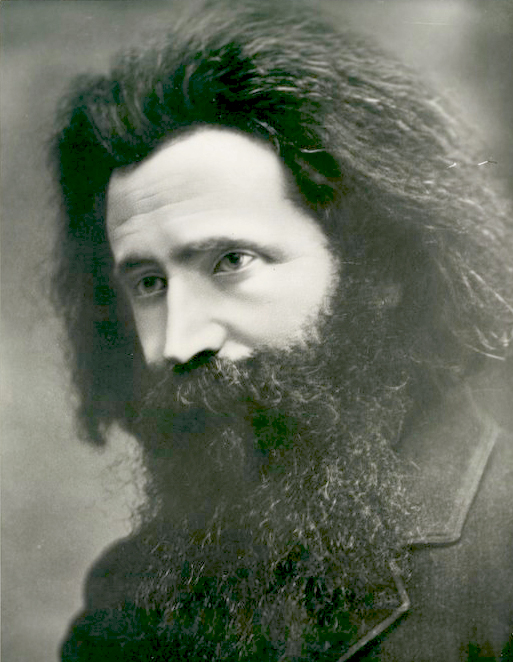

Kalonymus Kalman Shapira of Piaseczno (1889–1943) and Hillel Zeitlin (1871–1942) were two of the most interesting and creative minds in the Hasidic world of interwar Warsaw. Shapira, the scion of an important Polish Hasidic dynasty, served as a traditional communal leader but was much concerned with sparking a religious and spiritual renewal among the Hasidim of his day. He published only one book during his lifetime—Hovat ha-talmidim, published in English as A Student’s Obligation—but his other posthumous works reveal that Shapira developed a remarkable concern with mystical teachings, spiritual education, and contemplative techniques. He is best remembered as a spiritual leader in the Warsaw Ghetto. Shapira’s wartime sermons, recently republished in a magisterial critical edition by Daniel Reiser under the author’s own original title—Derashot mi-shenot ha-za’am, Sermons from the Years of Rage—is perhaps the final work of traditional Jewish scholarship to have been written on Polish soil. Shapira endured the ghetto uprising and was murdered after having been deported with the other remaining survivors in early November 1943. The date of Shapira’s death is a matter of dispute, but 4 Heshvan (which this year falls on November 2, Parshat Noah) is celebrated as his yahrzeit by his descendants and students, as well as by the many contemporary seekers and readers who have found inspiration and interest in his works.

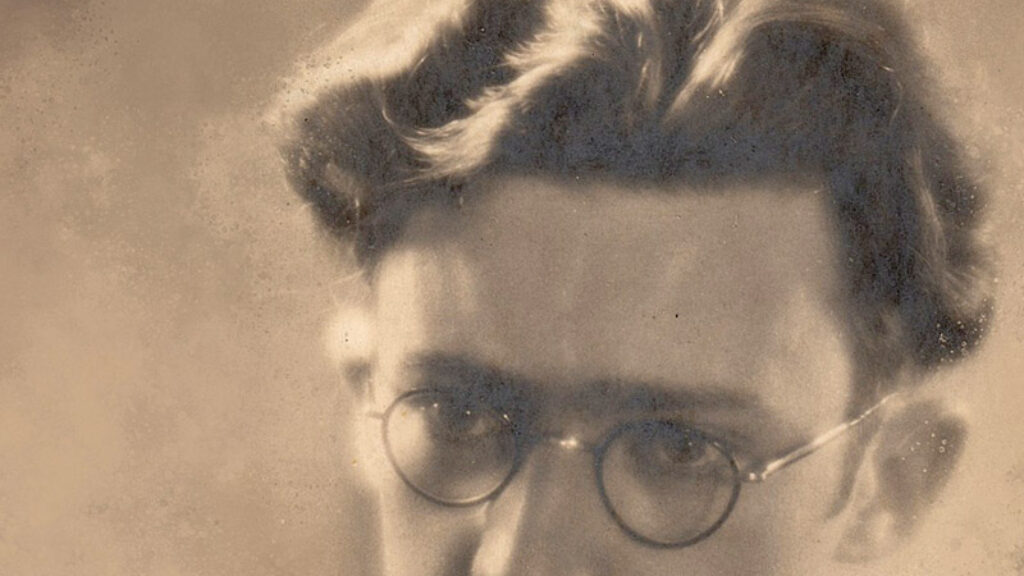

Zeitlin was raised in a Chabad family in White Russia and steeped in the Hasidic contemplative tradition. Zeitlin enjoyed an energetic devotional life in his youth, a period that he later described as being filled with a rich, mystical intoxication with the Divine Presence. Yet, in his adolescence, Zeitlin became increasingly troubled by philosophy and higher criticism of the Bible, and his confrontation with modernity led him away from the world of Hasidism. A voracious reader, he came to see his life’s task as bringing the philosophical enlightenment of the Yiddish world to the Hebrew reader. His first two significant published works were on Spinoza and Nietzsche, but he was also deeply interested in Schopenhauer, Tolstoy, William James, and Lev Shestov.

All of these currents fed directly into his way of understanding Jewish mysticism and his decision to preserve the legacy of early Hasidism by rearticulating a vision of Jewish spirituality that was compelling to contemporary (and future) seekers. Until his death on the road to Treblinka in 1943, he lived at the center of Warsaw’s teeming intellectual and highly partisan political life. Zeitlin was an enigmatic figure, dressed in a Hasidic caftan yet tirelessly writing on spiritual and political issues for the secular Yiddish and Hebrew press and choosing to operate within an almost entirely nonreligious milieu.

We might best describe Zeitlin as a confirmed neo-Hasid, though the term is somewhat anachronistic. Zeitlin often describes his spiritual vision as “the new Hasidism” (ha-hasidut ha-hadasha), offering an intense, expansive, and universalistic path rooted in the legacy of the Ba’al Shem Tov. He criticized contemporary Hasidism as having lost its original vital core. Its leaders, Zeitlin thought, stifled authentic religious expression with their rigid social hierarchies, political associations, and their rote spiritual observance. His review of Shapira’s book, however, shows that Zeitlin understood that Shapira was offering an alternative Hasidic vision.

Shapira’s Hovat ha-talmidim is, as Zeitlin understood, a sophisticated work on the art and craft of spiritual education meant for parents, teachers, and students. But he astutely notes that the work is far more than an exploration of pedagogy. Hovat ha-talmidim serves as a gateway into the conceptual and devotional universe of Hasidism, and Zeitlin’s review cites a series of examples from the work that illustrate Shapira’s devotional approach to study, prayer, and the religious life. Though Zeitlin is disappointed in the book’s conventionality and believes the work lacks the depth and originality of early Hasidism, he lauds Shapira’s psychologically sensitive approach to education and his emphasis on awakening the unique soul of the child rather than encouraging conformity or rote memorization, then, as now, mainstays of Hasidic education. Zeitlin also perceptively highlights an interesting complement to the holistic approach to devotion: Shapira’s ascetic impulse, one reflected in the writings of his Hasidic lineage. There is an unmistakable irony in his appraisal of Shapira’s concise but poetic prose; Zetilin’s own romantically inflected neo-Hasidic writing is often unbearably bombastic, and this elevated rhetorical style is quite apparent in the excerpt below.

One further point of connection between Zeitlin and Shapira bears comment. Zeitlin longed for a rarified and reinvigorated Judaism, one based on his idealized vision of early Hasidism and also deeply tied to the image of the circle around Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai in the Zohar. In the mid-1920s, he issued a series of calls to establish Yavneh, an elite and intimate religious brotherhood grounded in his religious vision. At some point in the 1920s, Shapira wrote a pamphlet entitled Benei machashava tova, outlining the basic principles and structures of a close-knit mystical fellowship meant to renew the contemporary Hasidic community. Similarities between their religious projects are unmistakable. We cannot be sure if Zeitlin and Shapira knew one another, but it is hardly imaginable that they did not meet. Both were very well-known public figures, they did not live far from each other, and both were eventually imprisoned in the Warsaw Ghetto. Zeitlin’s review of Hovat ha-talmidim, published in a Hebrew periodical in 1934, represents the intersection of two fascinating spiritual minds destroyed by the Holocaust.

Now, I have opened to the first page of a certain Hasidic book that was published in 1932, and on the title page it says: “The book Hovat ha-talmidim, written by our holy eminence, our teacher and master, the tzaddik and holy luminary, the pious and ascetic, crown of our head, the child of holy ancestors, our sacred teacher Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish [as he was popularly and affectionately known], may he live for many long and good years, head of the rabbinical court of the holy community of Piaseczno.” I opened up to the second page, and these lines shone before my eyes: “The book Hovat ha-talmidim is intended to reach the essence of the student, to reveal his soul, bringing it forth and instructing it in Torah and worship, in the paths of holiness, and to connect it to God, with commands and instructions to conduct in them with thought, speech, and deed.”

It seems, therefore, that before my lies a work of pedagogy, an educational book that instructs the Jewish youth. The instruction is not worldly or cultural, but “instruction in the paths of Hasidism.”

I have read the work and found in it much more than promised by the title page. Our author—the Rebbe [Admor] of Piaseczno—expressed on the title page only the tiniest of allusions to the rich and polychromatic contents.

The book is, as mentioned, one of Hasidic education, but in addition it is an introduction to Hasidism. Not simply as it says on the title page: “Also appended are three discourses explaining, in brief, the secrets of Hasidism and the fundaments of Kabbalah necessary for students and youths [to grasp] Hasidic worship, each according to his situation.” In truth, the entire work is an introduction to Hasidism, not just for “students and youths,” but for anyone who wants to enter the palace [heikhal] of Hasidism via the inner path of mind and soul. This Hasidic book by the Rebbe of Piaseczno does not include the abysses or heavens—together—of the Bretslaver and his students, nor does it have the divine philosophy and sublime songs of the soul of Chabad. It does not have the deepest depths of the “Jew” of Pshiskhe, of Rabbi Bunem, and the Kotsker and their followers. It does not have that searching fire, that yearning for the living God that bursts out without restraint from Volhynian Hasidism. Rather, [it presents] the Hasidism that is now commonplace across most of Poland; the average Hasidism, diluted, combining mussar, homiletics, and Kabbalah with introductions of the Besht and his students; the Hasidism that is closer to the concepts of the intermediate [person] among those who tremble before God’s word. Its goal is essentially to uplift the average person, measure by measure, raising him up and instructing him slowly and surely until his eyes are opened—each according to the mediations of his heart—to the “light hidden away for the righteous,” and to look just a bit with this eye upon the world.

Our author innovated something very important in the study of Hasidism: He introduced into it an order and method, opening it to psychology and pedagogy, both practical and theoretical, although he dresses it up in different places in a particularly poetic garb.

In many instances in this book, we might imagine ourselves reading the Nineteen Letters on Judaism and Horeb of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch. I do not know if our author read Hirsch’s works or if they influenced his particular style and pathos, or if there is simply a closeness of souls that elicits a single style from two people distant in time and space, as well as across [different] intellectual states and disposition. An advantage that Hirsch’s style has over that of our author is that the former has a richness of expression, sublimeness of concepts, and an outpouring of colors. The latter’s advantage over Hirsch, in these places, is that our author knows restraint and measure [ketzev u-middah]even when overcome with the spirit of poetics and the heights of the mountains of imagination. Restraint and measure even when he burns with a holy fire and longing for the Infinite such that his soul quite nearly expires. Restraint and measure, the power of restriction [tzimtzum] and holding back—these things make our author an artist of the pen even though he did not intend at all to beautify his craft or to be crowned with the laurels of a poet.

A few examples of our author’s particular style, of his passion, of his educational instruction and his particular interpretation of Hasidism:

Gaze, Jewish youth, upon the radiant splendor of Israel and its inner essence, the essence of the purest heaven within them. Be concerned about our terrible darkness, and yearn to return, to ascend and draw just a bit nearer to our God. Eventually, your soul will be aroused—yearn and express yourself, wrapping yourself a prayer like this:

“O, dear God, you have forever been our father, and we are Your children. Forever, and from the moment when a Jewish boy or girl just bursts from the mother’s womb, our enemies are many and bitter, our afflicters are harsh and strong, [trying] to disconnect us from you, heaven forfend. But each one of us is ready to give up his soul for you, O God, and even the tiniest lamb from among us stretches out its neck for you. There is no limit to the sacrificial offerings that have been burned; there is no investigating our constant afflictions, across the days of our lives, which suck out our life-force. For your sake, so as not to be separated from you, we receive all of this with love and joy. So are we all, and so am I before you. I am thus now and will be forever, my father and king. But you have led us forever, we saw the glorious Shekhina eye to eye, and You spoke to us like a loving father to his children. How good it was for us then, but now it is not so now because of our sins, and You have ascended on high, shutting heaven before us, you do not speak or answer, [there is] no prophet or seer. Please, O God, to whom have you abandoned the tiny flock, the remnant of Israel, in a forsaken desert like this; it is a place where they damage our body and soul. My Father in Heaven, my soul is afraid to be without You for even a moment. Draw near to us, and be close in days past.”

Please remember, pious student, how many great and wonderful people are jealous of you. They yearn, saying, “Who will give me now [the vitality] of a youth and a young person, to devote and give the whole day to God.” How many of them yearn to be in a body and soul that longs for God, but their years are hard upon them. Everything remains in your hands. Will you lose this precious gem, saying, “I will serve God when I am older; I will repair [my fallen qualities] when I am mature”?

The Mishnah says: “One who studies as a child, to what may he be compared? To ink written upon a fresh paper. One who studies in old age—to ink written upon a paper that has been erased.” [Avot 4:20] So it is in all matters: in straightforward study, in Hasidic [devotion], and in repairing the soul. Many people know about worship and healing the soul, yearning and even forcing themselves to do it. Yet they waste their years in just compelling and pressuring themselves, and so forth. Such is not the case with you, delightful children. If you begin in your childhood and work on this in your adolescence, then Hasidism will become your flesh and blood. Even if you fall, you will not slide backward. Even if you must sometimes cease [the work], you will not become mired in the swamp. You will not be forced to waste your years, just to prevent falling and rising up from the dust and mud.

In truth you can, O Jewish youth, bring forth from within you [positive] tendencies and repairs that you did not suppose [were present] and that you will do not yourself understand. You can, for example, arrive at a good and strong will, stronger even than you, to which your entire self is subservient. It compels you to fulfill it against your wish and without any excuses or explanations. You will suddenly feel within yourself the strong spirit of God, breaking mountains and shattering stones, touching you and lifting you up to this work. All obstacles will be broken down, and anything holding you back will be destroyed. The Lord is God, and you are His servant. You must serve Him.

Know, my precious child, that we do not err. People of the world are wrong in considering this world that God created, for it is a treasure trove of desires and bad inclinations. One who wishes to serve God must go out and distance himself from the entire world. Because of this, they are far from worship and sanctity for all of their days, sunken in the follies of this world. They are like one who sees another person drowning in the river and declares that the waters are themselves evil since they were created only to kill. How foolish is such a person! Can one live without water? Because of this insane person, should we not use water correctly? If instead of giving life to plants, animals, and people, one kills himself in them, are they bad? So it is with the whole world, a world created by God. Even below the world, in all of its curves and twists, there are paths, burrows, and tunnels that lead to its master, the Master of the World. All lack depends upon the person who uses the world for wickedness rather than for good.

Faithful student, guard your childhood and be zealous in your youth. How pleasant is childhood, and how sweet is youth blessed by God! It is like a river of honey, like the river that runs from Eden to the person across years as a thirst-quenching stream. Even in old and hoary age, its vitality remains vigorous, its elixirs grow and flourish. The body grows old as its powers weaken, but the fire remains; [the body] is warmed by its heat and set aflame by its fire. What fool would lose this, what crazy person would defile and stop up the source of his life?

If you wish to clarify whether your arousal is truly a revelation of the soul, drawing near to the supernal purity [tohar], or if it is simply a deceitful feeling, gaze upon your [moral and ethical] qualities. If, in spite of it all, they have been repaired even to a small degree, then you may know you have lifted a bit [of dirt] from the ugly garment. Their holy source has been partially revealed. But if you have removed nothing of their wicked [exterior] or diminished their lowliness, then your arousal has accomplished nothing. Perhaps it has even compounded their shortcomings!

After your arousal, after your fitting prayer, while your spirit is warm and the holy visions flower before your eyes, hasten to gaze upon the lowness of your qualities and to be afraid, to see into the pit of snakes and to become bitters from the holy mountain up which you climbed. Trample and correct them, shattering their wicked garments and reveal their essential holiness.”

Pearls like this appear throughout this work, which encompasses some 170 pages. In Hovat ha-talmidim, our author, the Rebbe of Piaseczno, wraps present-day Polish Hasidism in a garment more beautiful than it has ever had. He enriches educational literature with this very valuable work, introduces light and renewal to the young talmudist slaying himself in the tent of Torah. In his book, the author always unites great joy in God and in His creations with extreme asceticism with the withdrawal and austerity of the talmudic student, even though he is ostensibly dissatisfied with asceticism. It seems to me that sometimes he demands too much of the talmudic student, gracing him with more goodness than he can constantly receive. Our author runs from the mitnaggedic mussar that shatters the person, subjugating and casting him down, the author always remembers the verse “strength and joy are in His place” [1 Chron. 16:27] and the teaching “Shekhinah rests not amid sloth and sadness . . . but amid the joy of the commandment.” He is, nevertheless, occasionally drawn to the same mussar that includes much melancholy. The work includes other things that are not to the taste of one who ascended to the house of God, not through the path of asceticism (from which even Bratslav Hasidism is not free), but through the path of joy and connectivity [devekut] of the Besht [the Ba’al Shem Tov] and the early Chabad leaders. Nevertheless, this book is a wonderful gateway and introduction for all people, and in particular for the modern Jew in whose heart a thought of true repentance has sparked, to enter the palace of Hasidism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

18 Questions with Jeremy Dauber: The Purim Edition

Who ruled the Borscht Belt: Allan Sherman or Lenny Bruce? Jewish comedy expert Jeremy Dauber casts his vote in a humorous interview—just in time for Purim.

Going Under with Klinghoffer

When it came to New York’s Metropolitan Opera this past fall The Death of Klinghoffer faced angry—and, it must be admitted, some pretty shrill—demonstrators.

The Tikkun in Sutzkever’s Work

Elie Wiesel explores the soul and purpose of Holocaust poetry.

Jewish Pugs

A successful Jewish jock, demonstrating strength and physical courage, nicely rounds out Jews’ sense of completeness as human beings.

Yisrael Medad

"published in a Hebrew periodical in 1934"

which one?