Jewish Pugs

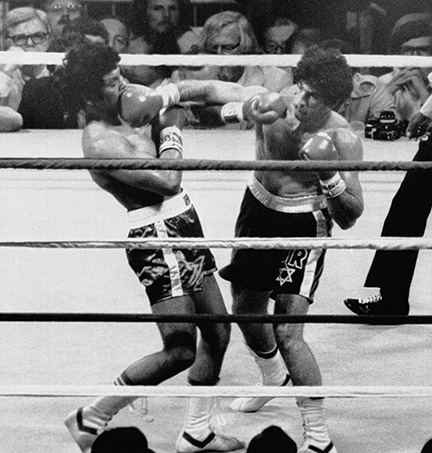

Impossible, I suspect, to convince anyone under 50 how central the sport of boxing was to American popular culture in the first five decades of the last century. No single event—not the Olympics, the World Series, Wimbledon, the Rose Bowl—held the attraction for Americans interested in sports that a heavyweight championship fight held. Nor did it even have to be a championship fight. At the age of 14 on the Friday night of October 26, 1951, I was sitting in the Nortown Theatre in Chicago when they stopped the movie—stopped the movie!—to announce that Rocky Marciano had just beaten Joe Louis in the eighth round of a scheduled 10-round fight at Madison Square Garden.

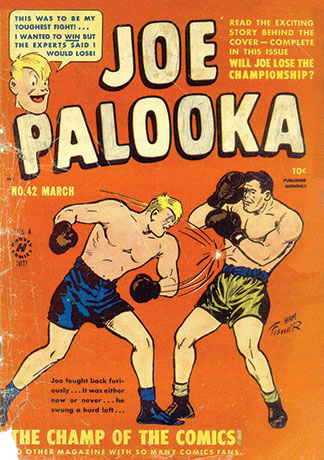

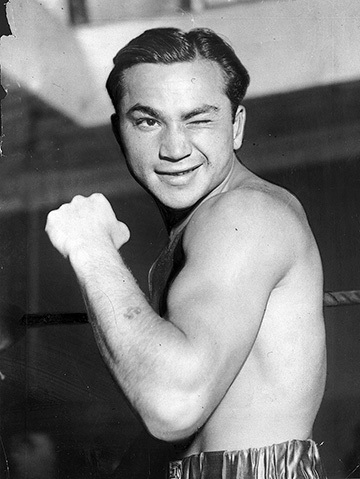

Prize fights, amateur and professional, were ubiquitous: staged in small clubs and at major stadiums, broadcast over the radio (the Friday Night Fights sponsored by Gillette Blue Blades—“for the quickest, slickest shave of all”), and, beginning in the late 1940s, on television, often several nights a week. A comic strip called Joe Palooka, about a heavyweight boxing champion, was widely syndicated during these years and was a favorite of boys. At the age of 12, I could name the champions and leading contenders in every weight division, from flyweight (108–112 pounds) to heavyweight (no limit), but then so could any normally sports-obsessed kid, and in my boyhood there were lots of us. When Joe Louis defeated Max Schmeling of Germany in a return-match first-round knockout in 1938—a fight, alas, before my time—Americans felt that it was a victory over the Nazis, and Louis became a national hero, even though the United States would not enter the war for another three and a half years. Boxing was immensely popular, international, a form of patriotism by other means, in a word, big.

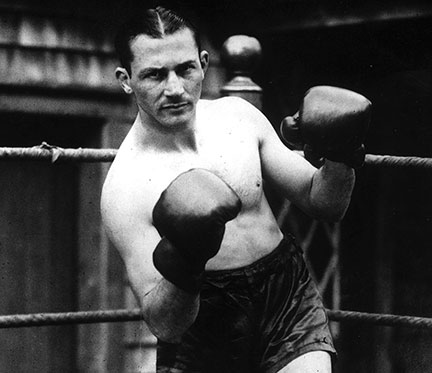

A Canadian who had arrived in this country from Montreal at the age of 17, my father had no interest in baseball or football. Boxing, though, did interest him. He took me to Golden Gloves (amateur) fights at Rainbow Arena on Chicago’s north side, and himself was lucky enough to have a ticket for the second of the three brutal Tony Zale-Rocky Graziano middleweight championship fights.

In Montreal my father had grown up with two brothers, Danny and Sammy Spunt, who owned a boxing gym, the Chicago equivalent of Stillman’s in New York, called The Ringside. In the late 1940s Chicago seemed safe enough for an 11-year-old boy to mount the El and travel alone downtown, which, for a brief period, I did, to hang out at their gym. Danny Spunt was especially kind to me. He directed me to a file cabinet filled with signed 8″ x 10″ glossy photographs of all the boxing champions and leading contenders of the day, and told me to take my pick: I took home a Willie Pep, a Gus Lesnevich, and a Sugar Ray Robinson. As long as I didn’t get in the way, which I wasn’t about to do, I could watch fighters spar, shadow-box, and work out on the light or heavy bags. The atmosphere couldn’t have been more masculine, the smell of the joint a rich brew of liniment, leather, cigar smoke, and heavy sweat.

One day Danny Spunt took me into the locker room, where he introduced me to a seated fighter leaning against a locker after a workout, his fists taped, his only clothes a heavy leather Everlast protective jock.

“Kid,” Danny said, “meet Tony Zale, the middleweight champion [he pronounced it “champeen”] of the world.”

“Hi, champ,” I managed to gurgle.

“Hi, kid,” Zale replied. No meeting since in my life has impressed me half so much.

One of the leading younger fighters who trained at The Ringside in those days was a black welterweight named Johnny Bratton. His manager, a heavyset man in a green corduroy jacket and a coral-colored hat with a large feather in its band that he wore indoors, had flashing gold teeth. In 1951, at the age of 24, Johnny Bratton won the welterweight title by outpointing Charley Fusari. Less than two months later, he lost it to “Kid” Gavilan, a flashy Cuban whose arsenal included an uppercut that seemed to begin around the knees called the bolo punch. Afterwards it was revealed that Bratton fought Gavilan for some 10 rounds of their 15-round fight with a broken jaw. Tumbling downhill from there, he was reduced to fighting bums until he himself was a bum other boxers fought on their way up. Years later I read in the Chicago Sun-Times that he had been picked up by the cops around Chicago Stadium while attempting to sell a stolen fur coat. He spent much of the rest of his days in an insane asylum in Manteno, Illinois, and died in his mid-fifties. The other, not altogether uncommon, side of the boxing story, Johnny Bratton’s.

By the time I became interested in boxing, Jewish boxers were no longer active. Such glory as Jews had derived from competing in the sport was long in the past. But even this past glory lived on. Across the courtyard in the building in which we lived on Sheridan Road in Chicago resided the Kaplans, Ida and Irv, Ida being the sister of Barney Ross, who in his day held the lightweight, light-welterweight, and welterweight championships. The father of a classmate, Billy Schoenwald, who later became a good friend, was Irv Schoenwald, a successful fight promoter. In the 1940s and early 1950s a former heavyweight, the slightly punchy “Kingfish” Levinsky (his name derived from his family’s fish business on Maxwell Street, the city’s permanent flea market), used to sell garish neckties out of a suitcase to Jewish businessmen who worked in the Loop. My

father bought one off the old pug.

Mob corruption, of course, was always hovering on the edge of boxing, sometimes damnably close to the center. I had another friend whose father succeeded beyond all his imagining selling aluminum awnings, which allowed him to invest in boxers. His most famous fighter was a heavyweight named Ernie Terrell, who was WBA champion from 1965 to 1967, when he was beaten badly, humiliatingly, by Muhammad Ali. My friend’s father got tied up with the Mob in Chicago—he had installed awnings for Tony “Big Tuna” Accardo, the head of the Chicago Syndicate and a frightening figure—whose thugs wanted to control his fighters. At one point, he was pursued by a hitman named Felix “Milwaukee Phil” Alderisio, had to go into hiding, and, after being rescued by the FBI, testified about Mob interests in boxing.

Mike Silver’s Stars in the Ring, an excellent account of “Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing,” is an elegant piece of bookmaking that is an outstanding specimen of a coffee-table book but also much more than that. The book contains photographs of the best 166 Jewish boxers (cauliflower ears are sometimes apparent; so, too, evidence of broken or flattened noses, rhinoplasty, one might say, by other means), along with biographical portraits of admirable concision tracing the trajectory of their careers.

Along with these biographies, Stars in the Ring provides essaylets on such items as the medical effects of boxing on the fighters; the grooming of future fighters who were newsboys defending their street-corner turfs; the Golden Gloves era; boxing in the Shanghai ghetto, in DP camps, and in Israel; and more. Silver chronicles the history of boxing from its bare-knuckles era, when the Sephardi boxer Daniel Mendoza “achieved something like superstar status,” to the reign of the Marquis of Queensbury rules, and through its television heyday. He also sets out the sport’s decline, both in popular appeal and in the quality of fighters; boxing, he regrettably allows, is the only sport in which the athletes haven’t gotten better.

Jews had always been prominent middlemen in the sport of boxing. They were, Silver writes, “promoters, managers, trainers, corner men, gym owners, equipment manufacturers, and magazine publishers.” He devotes a few pages to Nat Fleischer, editor and publisher of The Ring magazine and for decades the unacknowledged commissioner of boxing. Fleischer set up a rating system for boxers, argued for stringent medical examinations and rules, fought against the incursions of organized crime in the sport. “Sadly, after Fleischer’s death in 1972,” Silver writes, “The Ring began to deteriorate along with the sport,” a view seconded by the boxing historian Harry Shaffer, who believed that Nat Fleischer “is what held it [boxing] together.”

In the early decades of the last century, Jewish boxers were, if not preponderant, certainly commonplace. “The first four decades of the last century were a Golden Age for the sport of boxing in terms of status, the quantity and quality of talent, media coverage, and attendance figures,” Silver writes, adding: “It was no less a Golden Age for Jewish boxers.” He has discovered that there were more than 3,000 Jewish professional boxers active during this time, “or about 7 to 10 percent of the total number of professionals.” More impressive yet: “Between 1901 and 1939 there were 29 Jewish world-champion boxers—about 16 percent of the total number of champions.” In 12 different bouts for titles, both boxers were Jews. Silver continues: “In the 1920s, 14 of the 66 world champions were Jewish, placing them second behind Italians, who had 19 world champions, but ahead of the Irish, who had 11 . . . By 1928 Jewish boxers comprised the single largest ethnic group among title contenders in the 10 weight divisions.”

No other ethnic or religious group is likely to have been the subject of a work like Stars in the Ring. This is because no one exults like American Jews in the athletic prowess of their co-religionists. Who asks if Peyton Manning is a Lutheran, Tiger Woods a Catholic, Buster Posey a Presbyterian? For a superior athlete to be Jewish, though, is a high point of pride among Jewish men. I have myself sat in on countless conversations in which the question of whether one or another contemporary athlete is Jewish is discussed: Julian Edelman, wide receiver of the New England Patriots (yes), Stephen Strasburg, the pitcher for the Washington Nationals (alas, no). Is this because Jews, the “People of the Book,” prefer not to be taken as altogether too bookish? A successful Jewish jock, demonstrating strength and physical courage, nicely rounds out Jews’ sense of completeness as human beings.

Truly great Jewish athletes nonetheless have been less than abundant. Of those who qualify beyond question for hall of fame status, I can think of only five inarguable names: Benny Leonard, the lightweight boxing champion; Sid Luckman, the Chicago Bears quarterback; Hank Greenberg, the Detroit Tigers outfielder and first baseman; Sandy Koufax, the Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher; and Mark Spitz, the multiple gold-medal Olympic swimmer. Close but no cigar would be Barney Ross; Dolph Schayes, the elegant forward on the old Syracuse Nats professional basketball team; and Al Rosen, the Cleveland Indians third baseman. A small single room at the Holiday Inn might provide sufficient space for a Jewish Athletic Hall of Fame. The room would also require an ample walk-in closest to accommodate Jewish athletic oddities: for example, Moe Berg, major-league catcher and spy, who was said to speak six languages and was unable to hit above .240 in any of them; or Leach Cross (né Louis Wallach), known as the “Fighting Dentist,” who one night loosened two of his opponents’ teeth and the next day repaired them; and doubtless a few others.

Despite the Jewish masculine admiration for their own athletes, for years The Jewish Daily Forward, as Mike Silver notes, chose not to report anything about the large numbers of successful Jewish boxers. The paper relented only in 1923, when the lightweight championship bout between two Jews, Lew Tendler and Benny Leonard, known as the “Ghetto Wizard,” was such hot news the paper couldn’t leave it out. They ignored it until then in the belief that Jews should be interested in higher things, that boxing was, so to say, strictly for the goyim.

The various divisions between cerebral and physical, between sensitive and tough, between socialist and entrepreneurial, between neurotic and intensely commonsensical Jews have long been a source of endless wonderment, not to say immense amusement, to the Judenkenner among us, and reinforces the best definition I know of Jews, which is that they are just like everyone else, only more so. Still, the emphasis on braininess, as opposed to the physicality, of the Jews is a stereotype that hangs tough in public and indeed Jewish consciousness. (In concert with this stereotype, the true religion of the modern Jew, it has been said, is diplomas.) This ignores the Maccabean precedent of the Jewish warrior and of the proven toughness and efficiency of the Israeli Defense Forces, perhaps the only large-scale institution left in the world that can, thank God, claim both.

Stereotypes, too, bear a truth quotient. In the case of the Jews, many immigrant Jewish parents would have been dismayed to discover their sons were professional boxers. A number of the boxers featured in Stars in the Ring—Frankie Callahan (né Samuel Holtzman), Eddie O’Keefe (né Morris Edward Paley), Harry Stone (né Henry Siegstein)—changed their names not to de-Judaize themselves but to hide their boxing careers from their old-world parents. No one, surely, could accuse a heavyweight called Abie Israel of doing the same.

The Jewish name-changing of boxers is a leitmotif that plays through Mr. Silver’s pages. The lightweight contender Herman Gold became “Oakland” Jimmy Duffy. A junior welterweight named Morris Scheer became the second fighting Callahan, this one calling himself Mushy (after his Yiddish name of Moishe). A welterweight champion named Jackie Fields was originally Jacob Finkelstein. Perhaps the most elaborate nomenclatectomy was that done on John Dodick, a junior-lightweight champion in 1923, who began his career fighting under the name “Kid” Murphy, and then re-Judaized himself, once Jewish boxers became à la mode, as Jack Bernstein.

An epiphenomenon of boxing during its glory days was the battle of ethnics, chauvinism versus chauvinism. Jewish versus Irish, or Irish versus Italian, boxers gave an added flavor to a fight. Such must have been emphatically the case when Max “Slapsie Maxie” Rosenbloom fought the goyesquely named Joe “Hambone” Kelly. Jews, especially in New York, were among the leading fans of the sport, and fighters sometimes played to them by emphasizing their Jewishness. A Star of David on one’s boxing trunks, such as that worn by the heavyweight Max Baer, who was only one quarter Jewish, was not uncommon. An English lightweight named Harry Mizler wore trunks with a Star of David on his left leg and a Union Jack on the right. Mike Silver mentions two Jewish fighters who entered the ring draped in talleisim, one of whom added a properly wound tefillin round his arm and forehead. One assumes he removed them when answering the bell for the first round.

Through the years of intense Jewish emigration to America and on through the Depression, boxing was an alluring way to make a living for the sons of the lower classes. In the early decades of the 20th century no athletic events were better attended than prize fights, no financial rewards greater among athletes than those earned by boxers. Not every Jewish boy who went into the ring cashed in heavy chips at the close of his career. But if one fought regularly—and such was the popularity of the sport that many fighters had as many as two or three bouts a month—a serious income was available. A $20,000 payout for a night’s work was not uncommon.

Some of Mike Silver’s biographical entries are longer than others. The greater the fighter, the lengthier the biography: hence the longish biographies of Benny Leonard, “Slapsie Maxie” Rosenbloom (the sobriquet Slapsie derived from Rosenbloom’s slapping rather than punching his opponents, lest he injure his hands and be out of work), and Barney Ross. Many are poignant in their details. When available, Silver accounts briefly for the lives led by these men after their boxing days are done. Post-ring careers range from driving cabs to working as bodyguards, from running gyms and spas to coaching actors about boxing and appearing in films, to salesmen and owners of small businesses, and in one notable case—that of a Scottish flyweight named Vic Herman—to portrait painting. “[T]he majority of Jewish fighters,” Silver remarks, “were able to maintain a stable and productive life after their boxing careers ended.” Sad are the closing passages in his book in which dementia pugilistica and other neurological disorders are reported. Early deaths are not infrequent. Saddest of all are the few instances of European Jewish boxers whose lives ended in Auschwitz.

Vast numbers of Jews were boxers, but how Jewish were they, really? When with the British comedy group Beyond the Fringe, Jonathan Miller was asked if he was a Jew, he answered, “I’m Jew-ish,” by which I take him to have meant that he was born into Judaism but not, so to say, much of a practitioner. A notable exception among boxers was Barney Ross, whose father, like many an immigrant Jewish father, was devout in his Judaism; Silver describes him as “a Talmudic scholar.” No life seems to have been so divided between glory and sadness as that of Barney Ross. His father, Isidore Rasofsky, was murdered by a robber in his small grocery shop, his mother had a nervous breakdown, and the children were dispersed among relatives and orphanages. A three-time champion, a decorated Marine, and a powerful money-earner, Ross also suffered from just about every addiction going: nicotine, booze, gambling (the ponies), heavy drugs. Silver mentions his $500-a-day heroin habit, acquired after he became hooked on morphine given him for the wounds he received at Guadalcanal. Whether Ross turned to his father’s religion because of his troubles or out of piety for family tradition, Silver does not say. But he took his Judaism seriously and even began wearing tzitzit under his bespoke suits. Good to be able to report, too, that Barney Ross was an early supporter of Israel, working with the American League for a Free Palestine, helping to smuggle weapons to the Jews, and raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for the new state. Barney Ross died, at 57, of lung cancer.

I have not made an exact count, but as one reads through the lineup of biographical subjects in Stars in the Ring, the great majority of Jewish boxers chronicled in its pages fought in the lighter weight divisions: bantam-, fly-, light-, junior-welter-, welter-, and middleweight. Of Mike Silver’s list of “The Top 25 Jewish Boxers of All Time,” only four were middleweights or above. One could of course be a hard hitter even at 112 pounds, and some of the Jewish boxers listed had high knockout ratios over their careers, but the lighter weight divisions required speed, savvy, and general prowess. Brains over brawn seems to have been the tendency in Jewish boxers.

The greatest Jewish boxer of all was Benny Leonard, who was 5′ 5″ and during his fighting days weighed between 130 and 153 pounds. Silver describes Leonard as a brilliant boxer with “the heart of a warrior,” who had a “devastating right-hand counterpunch,” and who left the sport unmarked after 219 bouts. He collapsed refereeing a bout at St. Nicholas Arena in 1947 and died soon thereafter of a heart attack at the age of 51.

Stars in the Ring ends on a doleful chapter on how boxing has become “a marginalized and debased fringe sport.” The reasons are several. They begin at the top, or rather with the fact that there is no top. Boxing is a sport without a commissioner, which has allowed various rival organizations and federations to flourish, each creating its own titles and new weight divisions. The immediate result is that no one knows who is the champion of any particular weight or class—titles are spread out all over the joint. As Mike Silver puts it, by way of analogy with baseball, imagine the luster the game would lose if every year there were four different World Series winners.

Boxing went into a slump during and shortly after World War II, when so many young and some established fighters went off to war, though it looked to be resuscitated in the 1950s by television. Television, though, wrought its own complications. While it brought boxing an audience of millions, it also helped kill the boxing clubs and small arenas. Why pay to witness a bout in person when one can see it for nothing on television? This had the effect of depriving novice fighters of work and, more important, of the experience necessary to acquire consummate skill at their trade.

The reigning complaint among the contributors to The Arc of Boxing, a book Mike Silver published a few years ago, is that the fighters who came up after the early 1950s simply were nowhere near the caliber of those who came before them. To take one example, Floyd Mayweather, Jr., who is generally regarded as the best contemporary pure boxer, is described by one of the book’s contributors Tony Arnold as someone who uses his quickness “to overcome fighters with third-rate skills” but lacks real strategic intelligence and “ring guile.” The reason is, as Silver explains, a dearth of qualified teacher-trainers and the lack of experience on the part of fighters, who in an age of television haven’t fought enough to learn the manifold subtleties of their trade. “If you compare what boxing once was and what it has become,” a neuroscientist named Ted Lidsky, himself once an amateur boxer, is quoted in The Arc of Boxing as saying, “this is checkers in comparison to chess.”

As the skill among boxers diminished, the sport itself found new competitors for an audience in professional basketball and professional football. Mob interference, allowing only those fighters who were Mob-connected to get the best television bouts, didn’t help. Worse, according to Silver, have been the exploitative promoters Bob Arum and Don King, who, by arranging mismatches and scheduling over-hyped televised title fights, contributed heavily to making boxing the shabby sport it seems today. (The major cultural contribution of Don King may be limited to his name being the answer to the riddle that asks, “What does one get by combining Viagra and Rogaine?”)

Progress itself has worked against the future of boxing. With the long run of American prosperity that began after World War II, the old ethnic groups—Jews, Italians, Irish—ceased to need it to climb in status and prosperity. “The promise of America,” Silver puts it, “did not [any longer] have to come with a broken nose or cauliflower ear.” The vast majority of contemporary boxers are African Americans and Hispanics. With the current and quite legitimate alarm over head injuries in football, the future of the unforgiving sport of boxing, in which attacking the head of an opponent is usually a first priority, is further endangered.

The last major Jewish boxing champion was a man named Mike Rossman, a light-heavyweight and the first Jewish-American fighter to win a title in 40 years. (He won it in 1978 and lost it seven months later.) I confess to never having heard of Mike Rossman, and I wonder how many other similarly moderate obsessive sports fans like myself haven’t heard of him either. Nor had I heard of two recent Russian Jewish boxers, Yuri Foreman and Dmitriy Salita, both as it turns out Orthodox in their religious practice. But, then, as Silver laments, most of the young today are probably entirely unaware that Jews ever played an important role in a once immensely popular sport that “was important enough to give every ethnic group their first American heroes.” He adds that his reason for having written his book is that it is important to document the accomplishments of Jewish boxers, “so that future generations can acknowledge and appreciate how a people with no athletic tradition, and with so many doors closed to them, used their intelligence and drive to open another door to opportunity and eventually dominate, both as athletes and as entrepreneurs, what was for several decades the most popular sport in America.”

Mike Silver does not strike the autobiographical note until near the close of Stars in the Ring, when he mentions that on his fifth birthday his father bought him a pair of junior-size boxing gloves. When I was six years old, my father did the same for me. He also taught me the rudiments of the sport: jab, hook, right-cross, left-cross, uppercut, footwork, how to block blows. As for my own boxing career, my last fight, at age 10 outside Eugene Field Grammar School, was against a boy named Barry Pearlman. Stopped at the end of the first round by the school principal, it was pronounced a draw, and I retired soon after undefeated.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Pittsburgh Jews, Squirrel Hill, and the Tree of Life

In the wake of the recent massacre, a local historian tells the story of the Pittsburgh Jewish community and the 154-year-old Tree of Life synagogue.

Eden in a Distant Land

A new biography of Abraham Cahan unpacks how a young immigrant from Lithuania created the Forward and changed American Jewry.

Friendship?

Margot takes in the whats and wherefores of Judaism but is never quite able to grasp the why: why someone would wish to be Modern Orthodox and live a life according to the strictures of traditional Jewish law.

“I Am Talking to You Like King Solomon”

Saul Bellow once called Nabokov a “cold narcissist.” His letters to his wife, Véra, decisively dispel that common misconception.

diceman18

A very good article. I one went out with Lew Tendler's granddaughter.