The Warning Song and the Medlars: Two Stories

If this brilliant and original 17th-century Yiddish writer, who was born in Hamburg in 1645 and died in Metz in 1724, had seen the various renditions of her name in published versions of her work, she wouldn’t have recognized herself. Not in the name Glikl Hamel, and even less in the more commonly used and far more aristocratic appellation Glikl von/of Hameln, since these epithets substitute the name of her birthplace, Hamburg, with that of her husband, Hamel, which became attached to his first name, Chaim, only after he had left the place and settled elsewhere (for what good is it to be called Hamel when you live in Hamel?). Furthermore, such regional epithets were in those times used among Jews only for men, not for women. A woman’s name was, first of all, tied to her father (in our case: Glikl bas Reb Leyb) and then, after marriage, to her husband (Glikl eyshes Reb Chaim Hamel). If the husband died first—which Chaim did—she was identified as his widow (Glikl, almones Reb Chaim Hamel), unless she married someone else, which Glikl did in 1699.

No less than by the strange name, Glikl would have been startled by the titles and genre descriptions given by scholars, translators, and publishers to her writing: zikhronot or zikhroynes, memoirs or Memoiren, Denkwürdigkeiten, Tagebuch, autobiography, “The Life of,” and even “The Adventures of Glikl Hamel.” She herself gave her book no title. Nor did she describe it by genre. Failing to do so was unusual in those days, when most Yiddish books were explicitly named by genre: mayse (story), mayse-bukh (storybook), lid (poem), shpil (play), minhogim (customs), mesholim (fables), tkhines (supplications).

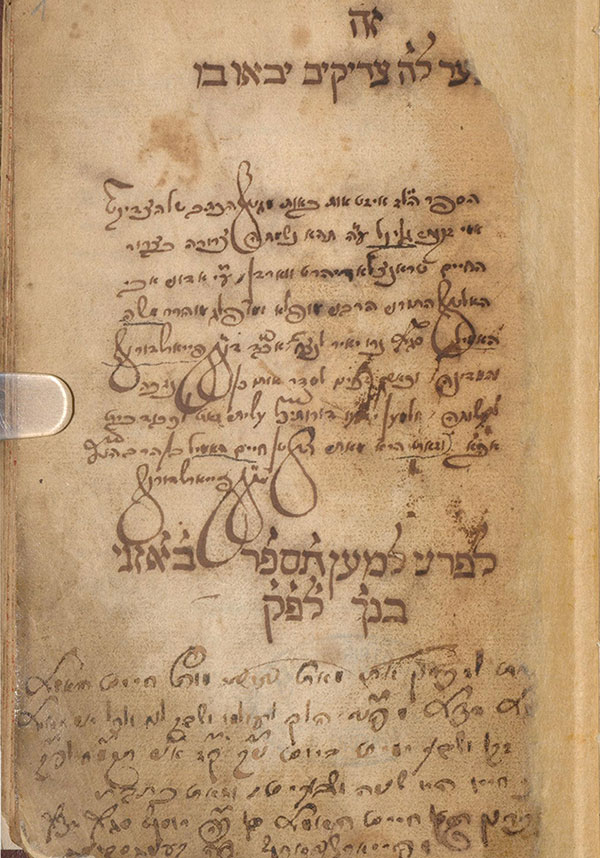

Why did Glikl refrain from giving her book a title or naming its genre? Was it only because she did not intend to have it published? Most Hebrew and Yiddish manuscripts—even if not directly intended for publication—were at that time given a title page or at least a title. But even later on, when Glikl’s grandson supplied the copy his father had made from her manuscript with a regular title page, he too abstained from providing a title. He did adorn the page with a biblical verse in the conventional manner, but when referring to the work itself called it simply ha-ksav (the writing). Not only did Glikl refrain from granting her book a title, but throughout her writing she avoided labeling it in any way, referring to it only as “it,” “this,” “such,” or “what I am writing.”

“I intend, God willing, to leave all this for you in seven little books, if God grants me life”—she says. “Therefore I think it would be most appropriate to begin with my birth.” Glikl’s “seven little books” (by which she means chapters) are so utterly different from anything published and known in the Jewish world until then that it is not surprising that she did not have a word to describe what she was writing.

Among those works written by Ashkenazi women before the Enlightenment that have come down to us—all but one or two of them in Yiddish—no other account of a personal life exists. Apart from private letters and the little poems a couple of young girls attached to the books they typeset at the family’s printing shop, the few available women’s writings comprise poems and prayers of various kinds, a sermon, and one major work, Rivka bas Meir Tiktiner’s book of moral instruction, Meynekes Rivke (Rebekah’s Nurse).

“I was born, so I believe, in the year 5407 [1647], in the holy community of Hamburg, where my pious, devout mother brought me into the world,” says Glikl at the beginning of her life story—she is mistaken, however, for the year was actually 1645—and she goes on to comment on the saying of the sages: “Better never to have been created than to have been created,” after which there is a page missing in which she is likely to have described the household and charity of her parents. It is the only missing leaf from the nearly two hundred the manuscript comprises. However, this can hardly be the reason for the fact that the period of the writer’s formative years, her growth and education, her evolution from childhood into maturity—precisely the topic that research of modern autobiography since Rousseau’s Confessions considers to be the key to and the quintessence of the genre—is almost entirely missing from her book.

All we know about Glikl’s short childhood—for a girl betrothed at the age of 12 and married at the age of 14 was considered an adult—comes down to no more than a few sentences: “I was born in Hamburg, but I heard from my dear parents and others—I was not yet three years old when all the Jews of Hamburg were served with an edict of expulsion and forced to move to Altona,” and “It was in my childhood—I was about 10 years old—when the Swede went to war with His Majesty the King of Denmark. I cannot write much news about it since I was a child and had to sit” in cheder. That she did attend a traditional elementary school in the heart of 17th-century Ashkenaz may strike the reader as surprising, but, in praising her father, she also remarks, “He gave his children, boys and girls alike, an education in higher matters as well as in practical things.” Did these higher matters include all the subjects of the contemporary curriculum for boys or just a few of them? And what does “practical things” mean—writing, arithmetic, correspondence skills, household chores, bookkeeping basics, rudiments of trade? And what kind of cheder was it? Who taught what to whom and for how long? Glikl does not provide any direct answers to these questions, but the form and content of her writing attest to her skills and disclose many of the sources of her knowledge.

Once Glikl decided to make her birth the starting point of her book, she necessarily had to draw upon the memories of others. The subject matter of these early episodes is mainly family stories, events in the Jewish community of Hamburg-Altona, and the figures of her direct ancestors. As a result, Glikl presents us with a wide gallery of male and female figures, most of whom she never met, but whose images—construed from the stories she heard—still thrilled and charmed her at the time of writing no less than they did in childhood. Most of these stories have a strong didactic flavor, but they also give a flavor of the Jewish experience of that time and place.

This is certainly the case with the first selection below, which tells the story of how Glikl’s father was saved by his clever trilingual stepdaughter from being cheated by a Gentile client who had pawned something with him and was scheming to get it back without repaying the loan. Although she was not there (Glikl was the daughter of her father’s second wife), she skillfully conjures the scene, using direct speech and subtly varying the language used by the characters. Thus, the father and daughter use the Hebrew-Yiddish word mashkon/mashkn for “pledge,” while the German word Pfand is used by the client. The client’s angry reference to the young girl as a hur (whore) is also implicitly refuted by Glikl’s description of her as a bsule (maiden). Here and elsewhere, a careful reading shows that Glikl’s text is not only a unique historical source; it is a subtle work of literary art.

When it comes to the narrative of her life, there is no doubt that marriage and a home of her own played a central role in the emergence of Glikl’s self-conscious identity as an individual and its consolidation into a genuine partnership of two. Glikl’s keen sense of partnership is clear from the start: “My husband, of blessed memory”—she recollects—“was very preoccupied with his business affairs; although still young, I did my part by his side. I do not write this to praise myself—my husband, of blessed memory, did not take advice from anyone but did whatever the two of us decided together.”

That is why no reader wonders at the reply of her dying husband when asked about his will: “I don’t know what to say. My wife, she knows everything. She should continue just as she was doing before.” Glikl does much more than that: She takes on the business herself, puts into practice her remarkable financial expertise and her competence in commerce, develops new original enterprises, and sees the business in precious metals and jewels grow and prosper under her sole management.

Even though Glikl explains right at the outset, time and again, that her writing was induced by her mournful state of mind after the loss of her husband, she does not follow the common practice of other 17th-century women of focusing primarily on the portrait of the devoted and adored husband and to append to it, with appropriate modesty, a briefer portrait of themselves. Glikl and her personal life story take center stage.

Although Glikl had 14 children, 13 of whom survived to adulthood, her normal pregnancies and births are merely mentioned in their proper place within the chronological sequence of events, and only when they involve an irregularity—illness, danger, death, a miraculous recovery or a funny episode—do they become worthy of detailed description. One such episode is her famous account of when she and her mother gave birth and were nursing infants at the same time in the same house, a remarkable event even then in a time of young marriages (and hence young grandparents). Another is the story, excerpted below, of the medlars (an acidic, curiously shaped spring fruit once commonly cultivated and eaten throughout Europe), which combines medical folk wisdom about women’s cravings with a vivid evocation of the experience of pregnancy and motherhood.

Because of the limited and often misleading information available concerning the education and spiritual world of Jewish women in the early modern period, the modern-day reader of Glikl’s work is likely to find the author’s decision to write, or even her literacy, somewhat surprising. In fact, many—if not most—of her female contemporaries were literate, not only those of similar socio-economic status. The very existence of a lively Yiddish literature offers clear evidence of this, for women were the most significant portion of its intended readership. It is reasonable, then, to assume that other women of her station had a similar education and that among them were others who, like Glikl, put ink to paper to tell the story—or episodes—of their life, yet only Glikl’s work has reached us.

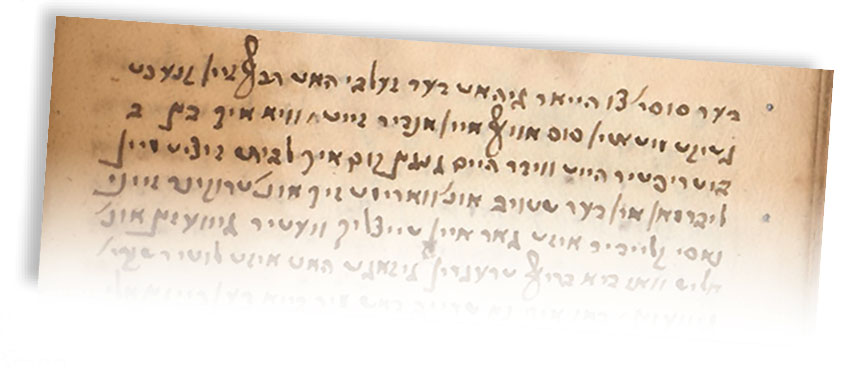

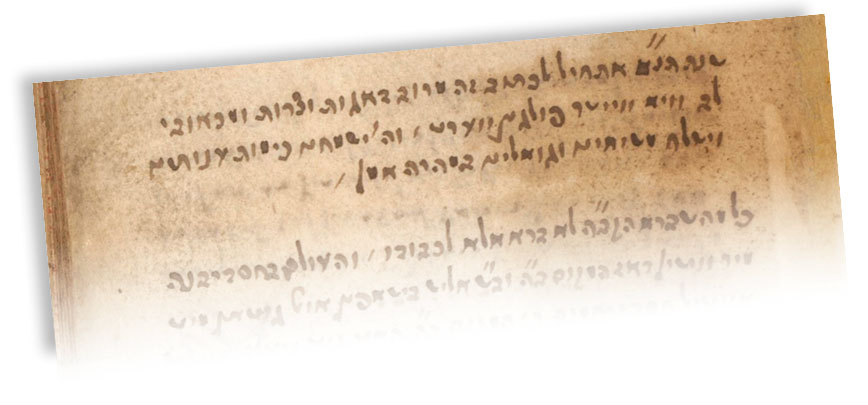

The original text of Glikl’s handwritten manuscript has not been preserved, but two copies, both made by her youngest son, Moshe, were passed down within the family from generation to generation, eventually finding their way in the late 19th century to the scholar David Kaufmann, who published the memoirs with some annotations in 1896. Since then, one of the copies went missing but for a small four-leaf folder, which is now held in the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. The other (virtually complete) copy is preserved at the University Library Johann Christian Senckenberg in Frankfurt-am-Main.

Glikl’s work is known mainly in translation because the original was reprinted only once, and its original language, Old Yiddish, was no longer understood by the general public even at the time of its publication by Kaufmann. A transcription into German was made by Glikl’s descendant Bertha Pappenheim (1859–1936). Pappenheim, a feminist who founded the Jewish Women’s Association, also posed as Glikl for a well-known portrait painted by the artist Leopold Pilichowski.

The brief entry on Glikl’s death in the Metz Burial Society Register records only that Mrs. Glik (!), the wife of the deceased community leader Reb Hirtz Levy (her second husband), died and was buried with a good name on Thursday, the second day of Rosh Hashanah of the year 5485, and lies at the right side of the widow Gelle. The longer entry in the Metz community Memorbuch describes her more elaborately as a pious, generous woman and good housewife who was “most wise in the trade of precious gems and also most learned in the rest of the respectable virtues.” No mention is made of her writing. In this, she is officially remembered like other women of her time and place, which only underlines the significance of her “seven little books” as a fascinating and extraordinary historical source.

The text from which these excerpts are taken is from the newly published Glikl: Memoirs, 1691–1719 (Brandeis University Press), which I edited and annotated; the English text is translated by Sara Friedman and adapted from my 2006 critical edition with Hebrew translation. As such, it is the first fully faithful English rendition of Glikl’s work.

Now, my father, of blessed memory, as I mentioned, before marrying my mother, may she live long, was married to another woman, by the name of Reytse, who was apparently an extremely talented person, a most capable woman who ran a large, respected household; she ultimately died without having any children with my father, of blessed memory. This woman already had an only daughter. In this way did my father, of blessed memory, gain—along with his first wife—a stepdaughter too, second to none in both beauty and deed. She spoke fluent French, which turned out one time to be most advantageous for my father, of blessed memory. For my father, of blessed memory, had received a pledge from a certain non-Jewish gentleman, valued at five hundred reichstaler. Well, after some time, this gentleman returned with two other gentlemen, seeking to redeem his pledge. My father, of blessed memory, suspecting nothing, goes upstairs to get the pledge. His stepdaughter was standing at the clavichord, playing the instrument so as to render the gentlemen’s wait less tedious.

The two gentlemen, who were standing near her, start conferring together: “When the Jew comes back with our pledge, we’ll grab it from him without giving him the money and get out of here.” They were speaking French, never dreaming that the maiden could understand them. As my father, of blessed memory, comes back with the pledge, she starts singing [a popular Hebrew song] loudly: “Beware! Not the pledge! Today—here, tomorrow—gone!”

In her haste, the poor girl couldn’t express herself any better. So my father, of blessed memory, says to the gentleman: “Sir, where’s the money?” Says the man: “Give me the pledge.” Says my father, of blessed memory: “I’m not giving any pledge; first I must have the money.” One of the men then turns to the others and says: “Fellows, we’ve been duped, the whore must know French,” and with that they bolted from the house, shouting threats. Next day the gentleman returns alone, pays my father, of blessed memory, the principal with interest, and redeems his pledge, saying: “Useful for you—you invested wisely when you had your daughter learn French,” and with that he went on his way.

After my husband returned from Hannover, where his father’s bequest was divided, as you have heard—this was about twelve weeks after his death, and I was pregnant with my son Reb Yosef Segal. Throughout the pregnancy my husband hoped fervently for a boy who would bear my husband’s father’s name again, as indeed happened, thanks be to God. Here I wish to set down a lesson for my children, one that is actually true: When young pregnant women spot different fruits or any other kind of food, whatever it may be, and they entertain even the slightest desire for it—let them not ignore this—they should eat of it and not follow their foolish heads. Ah, it will do no harm. It might actually be a matter of life and death for them, and the baby in the womb might very well—God forbid—be in danger too, as I found out for myself.

My whole life I had scoffed at hearing that women’s cravings could be harmful. I simply refused to believe it. On the contrary, when I was pregnant I’d often see succulent fruit at the market and examine it, but if the fruit seemed too dear I did not buy it, and I suffered no harm. But times are not all equal: When I was pregnant with my son Reb Yosef, I found out that things were otherwise. It so happened—when I was in the ninth month of my pregnancy with my son Reb Yosef—that my mother, may she live long, had to take care of something at a lawyer’s in the Pferdemarkt. My mother asked me to accompany her. Although it was far from my house, and late afternoon, at the beginning of the month of Kislev, I could not refuse her, since I was still full of energy.

So I went with my mother into town. At the lawyer’s we saw that a woman living opposite was selling medlars. I’ve always loved medlars. I told my mother: “Mother, don’t forget that I want to buy some medlars on the way back.” We took care of what we had come for at the lawyer’s, but when we finished it was very late, nearly nighttime, so we went on home, both of us having forgotten the medlars. As soon as I got home, I remembered the medlars and berated myself for forgetting to buy them. I did not give the matter too much thought, however, no more than one does when wishing for something to eat that is not available. In the evening I went to bed feeling fine, in a good mood, but after midnight the labor pains began and I had to send for the midwife. I gave birth to a baby boy.

My husband, of blessed memory, was told the good news right away; he was overjoyed, as now he had his father’s name again, the righteous Yosef, of blessed memory. But I saw the women who were present at the birth putting their heads together, whispering. I could not let it go; I asked what they were talking about. Finally, they told me that the baby’s head and body were completely covered with brown blotches. They had to bring a candle close to my bed for me to see for myself. Not only was the baby covered with blotches—he was just lying there like a heap of rags, moving neither hand nor foot, as though his soul was about to depart, God forbid. He wouldn’t nurse or even open his mouth. My husband, of blessed memory, saw it too, and we were desperate.

This was on Wednesday night—the following Thursday was supposed to be the day of his circumcision, but there didn’t seem any chance of that since the baby was growing weaker day by day. The Sabbath arrived, and on Friday night we held the welcoming for a baby boy, though there was no sign of improvement in the baby’s condition. On Saturday night, as my husband was making Havdalah, my mother was with me. I said to my mother: “Dearest mother, please, tell my Sabbath maidservant to come to me, I want to send her on an errand.” My mother asked where I wanted to send her. I said to my mother, may she live long: “I’ve been thinking what could have caused those blotches and the weakness, and I’ve been wondering if I was at fault when I wanted medlars and couldn’t get them, since I ended up giving birth that same night. I want to send the woman out to get a few schillings worth of medlars. I want to smear some of the fruit on the baby’s mouth; maybe God will have mercy and there will be an improvement.” My mother was angry at me, saying: “You always have this kind of nonsense in your head; the weather looks as if earth and sky were about to melt together, the woman won’t go out in this weather—in any case, all this is pure nonsense.”

I said: “Dearest mother, please do me a favor and send the woman; I’ll pay her whatever she wants, as long as I get those medlars. If I don’t get them I won’t have a moment’s peace.” So we sent for the woman and told her to go get some medlars. The woman hurried off—it was a long way, and the kind of weather that night you wouldn’t turn even a dog out of doors. It seemed to me a long time before the woman returned, as whenever you want something very badly—every minute seems like an hour. The woman finally returned with the medlars.

Of course, medlars are not the proper food for a newborn baby, because of the sourish taste. I instructed the nurse to loosen the baby’s swaddling clothes and sit down with him near the stove and smear some medlar pulp on his mouth. Although everybody laughed at me for this nonsense, I remained obstinate until it was done. The minute the nurse smeared the medlar pulp on the baby’s mouth, he opened his little mouth greedily as though wanting to swallow the whole thing at once, and then he was sucking and swallowing the pulp of an entire medlar, when just a moment ago he wouldn’t open his mouth even for a drop of milk or for the sugar-water you give babies. The nurse then handed the baby to me in my bed to see if he would nurse. The minute he was at the breast he started suckling like a three-month-old. By the time of the circumcision ceremony, all the blotches had disappeared from his face and body except for one spot on his side, the size of a broad lentil. The baby was healthy and well for the circumcision, a beautiful baby boy, circumcised at the prescribed time, thanks be to God. The circumcision ceremony was lavish, the likes of which had not been seen in Hamburg for a long time. And even though we had just suffered a loss of one thousand mark banco because Isaac Vas had gone bankrupt, on this day my husband did not give that a thought, so joyful was he at the birth of his son. And so, my children, you see that women’s cravings are not sheer nonsense, and they should not always be mocked.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Watching Game of Thrones, Waiting for Shavuot

Binge-watching the traditionless Game of Thrones while looking forward to the traditional binge-learning of Shavuot.

On Agnonizing in English

For the Hebrew reader, S. Y. Agnon is not merely canonical, he stands almost outside of time.

What Goes Into Survival: A Report from the Washington Rally

People came by the hundreds of thousands, schlepping by train, chartered bus, overnight flight. Students raised money from relatives. Federations funded last-minute airfare. It was a rally for people who don’t attend rallies.

Forging an Identity

How did a young Sephardi polyglot from Constantinople transform himself in Mexican society?

Paul M Weichsel

As you know, there is a “modern” Yiddish translation of the Gitl memoir, which I have read. I think it would be fascinating to “hear” Gitl read her story in her own Yiddish. I know that you have created a phonetic transcription, which I have. Do you think that it would be possible to produce an audio of parts of the memoir in the original?

Paul Weichsel