Israel’s Sea Change

One summer day in 1947, a ship about to sail from the London docks made history when it raised a new flag: the blue-and-white pennant of the Jewish national movement. There was a commotion on the riverside. “Thousands crowded onto the shores of the Thames,” an observer recorded:

This was the first time in history that seamen’s orders were given in Hebrew at the Thames dock. The appearance of the lovely Jewish ship with the Jewish crew on the Thames made a strong impression not only on the Jewish groups but also on the British trade and shipping classes.

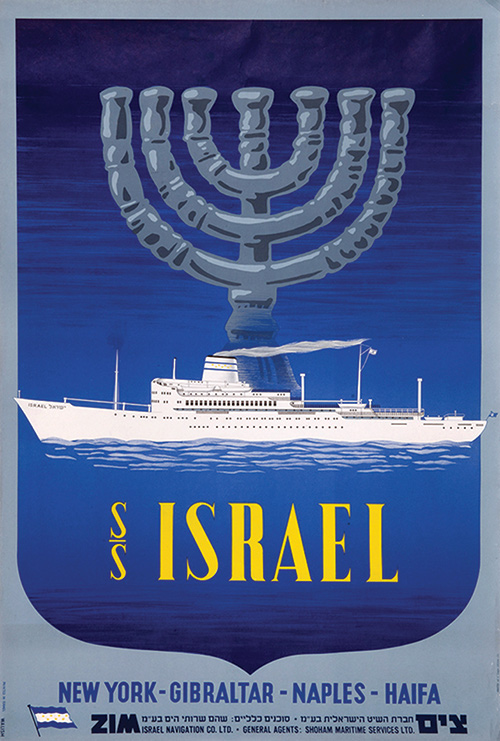

The ship, SS Kedmah, was the very first vessel belonging to the Zionist movement’s new shipping company, ZIM. It was sailing for the Land of Israel, still under British control, where its arrival was occasion for a national celebration in the Jewish home. Crowds came to the Tel Aviv beach to see the ship steam in, and five Piper Cubs flew an honor guard overhead (one carried Golda Meir). Children waved flags, and Zionist leaders delivered speeches praising what was then called the “conquest of the sea.”

As usual, the story—as told in Kobi Cohen-Hattab’s excellent new history, Zionism’s Maritime Revolution—wasn’t that simple. The new Zionist ship was, in fact, a refurbished English vessel with 20 years of rough service behind her, including the wartime evacuation of Singapore in 1941. She nearly broke down in the Mediterranean en route to the Yishuv. Saltwater got into the internal systems, the refrigerators didn’t refrigerate, the ovens didn’t cook, and the lights went out. The crewmen, who were Jewish, couldn’t stand the officers, who were British. The feeling was mutual, and eventually there was—inevitably, in those times of proletarian consciousness—a strike.

And yet the moment truly was historic, marking the launch not only of the national shipping company but of a significant Jewish presence in the Mediterranean. Within a year of Kedmah’s arrival, there would be a state called Israel with a navy, commercial vessels, a fishing industry, and ports—all of which would have seemed like a farfetched dream just two or three decades before, when a few Zionist enthusiasts and cranks under Turkish and British rule began promoting improbable visions of sovereign Jewish seamen sailing Jewish boats on what David Ben-Gurion once imagined as a “Jewish sea.”

The story of how this unfolded in the 30 years before Israel’s birth in 1948 is the subject of Zionism’s Maritime Revolution: The Yishuv’s Hold on the Land of Israel’s Sea and Shores, 1917 – 1948. While the early years of Zionist settlement on land have been exhaustively documented, it’s surprising to learn here from Cohen-Hattab, a professor of history at Bar-Ilan University, that so far there hasn’t been a comprehensive account of what happened on the water, no book that “has used a critical approach and the totality of existing sources to relate the story of the sea and its professions within the chronicles of the Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel in the modern age in the years prior to the establishment of the state.” The author has set out to fill the hole in the record, explaining how modern Jewish seamanship grew from a few failed fishing communes and handmade boats to the beginning of real naval power.

“Can it be imagined that, in a beautiful land such as ours,” bemoaned the Hebrew journalist Itamar Ben-Avi in 1912, “a land of abundant rivers, lakes, and seas, there is no water work, there are no seamen?” Ben-Avi, the son of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, father of modern Hebrew, was famously the first child in modern times to speak Hebrew as his mother tongue. He knew something about national rebirth and was upset to see this particular part of the process neglected: He wrote those lines after two groups of Jewish fishermen who’d come to practice their trade in the Land of Israel—one group from the Caspian and one from the Volga—had given up. Lacking boats, nets, and help from the Zionist establishment, they’d gone back home.

At the time, the land’s main port, Jaffa, was controlled by Arab porters and sailors. Few Jews had anything to do with the water at all. The early Zionists were focused on redeeming the soil, and their ideal was the farmer. The sea was a way to get here from Europe, but once you were here—lifted physically and humiliatingly from your ship and into a small boat at Jaffa by Arab porters—there wasn’t much point in thinking about it further. The future lay inland.

The slow change in this attitude can be credited, as in many other aspects of the Zionist enterprise, to individual enthusiasts. A key character in this case was Meir Gurvitz, a math teacher in Tel Aviv in the 1910s and 1920s who was described by contemporaries as an affable maritime fanatic: “Indeed, the man was wild for one thing, the sea, and he wished to infect others with his madness.” Born in Estonia, trained in Paris and Geneva, with a doctorate in marine studies from Seattle, he was described by one of his students as “an unusual man, wearing, always, a black suit, with a jacket zipped to his neck” who would “would walk alone back and forth in the yard, and appeared to be murmuring in an eternal mysterious monologue.”

It was in large part thanks to Gurvitz’s efforts that the Pioneer Motor Boat Co. was established in 1919, with one ship: Hehalutz (The Pioneer), a converted sailboat that had been rigged with a 30-horsepower engine originally built for a truck. (One of the crewmen was another exceptional character, Arie Bayevsky of Helsinki, a former Russian navy captain who’d converted to Judaism and embraced Zionism, and was “part of nearly every idea in the maritime enterprise in the Land of Israel in the twenties and thirties.”) Hehalutz made runs around the eastern Mediterranean, even helping evacuate Christian victims of a Muslim mob attack in Sidon and Tyre. But it wasn’t much of a ship, and it sunk at Jaffa in 1921 after just two years at sea. Many of the early maritime enterprises had that kind of end.

If Jewish maritime efforts ended up succeeding, Cohen-Hattab tells us, it was thanks in part to two important competitions. The first rivalry was with the Arab sailors, workers, and unions who controlled the sea and the Jaffa port, and who became more hostile as Jewish immigration increased. When Arab workers wouldn’t repair Jewish ships, the Jews built their own shipyard in Haifa in 1933. When the Jaffa port became less accessible to Jews and was eventually closed to them altogether amid the anti-Jewish and anti-British riots of 1936, the Zionists opened their port in the city they’d just raised from the sand, Tel Aviv.

The first captain in charge of the port was another of Zionism’s great nautical pioneers: Volodia Itzkovitz, who’d been the only Jewish cadet at the Odessa naval academy and was by then going by the name Ze’ev Hayam, literally, “Wolf of the Sea.” The docks were inaugurated with ecstatic parades and speeches, and this, Cohen-Hattab believes, was the true moment of revolution:

The establishment of the Tel Aviv port facilitated—for the first time—a vision of the Mediterranean Sea as the continuation of the land. It could now be seen not only as a natural boundary but rather as a space connecting the Land of Israel to the world, linking the Yishuv in the Land of Israel to Diaspora Jewry across the sea.

The same Ben-Avi who’d bemoaned the lack of Jewish sailors 20 years before was inspired, once again, to pick up his pen. He was in a better mood this time. “The west is our foundation, it is our window to the expanses of the entire world and our gateway to the very land we yearn for,” he wrote. “What Venice and Genoa did for Italy, and Hamburg and Bremen for Germany, Copenhagen for Denmark, New York for the United States—Tel Aviv will do with its perfect port for renewing Judah.”

Like many of the Zionists’ maritime fantasies, that one, too, didn’t quite materialize: The Tel Aviv port was active for a few years until World War II and again after the war until 1965, when its activities moved to better facilities down the coast at Ashdod. The Tel Aviv “port” is now free of unseemly cranes or longshoremen, and instead has cafes and a nice boardwalk frequented by hipsters; the only detail that an old sailor might find familiar are all the tattoos.

The second maritime competition of those years, only slightly less bitter, was between the dominant Labor Zionists, led by Ben-Gurion, and their rivals, the Revisionists of Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Revisionists took the lead in maritime activities and accused the socialists of shamefully neglecting the sea. One of the most vocal Revisionists, Capt. Jeremiah Helpern, linked this to ideology: The socialists, he thought, were discouraging fishing as too individualistic and too distant from the communal lifestyle of the kibbutz. The Revisionists set up a sea training school at Civitavecchia, Italy, where cadets practiced on a boat called Theodor Herzl under the tutelage of an Italian captain until the operation was shut down by Mussolini in 1938.

When, in 1937, a group of the school’s 45 graduates sailed to Palestine aboard the Sara A in a demonstration of their nautical prowessand triumphantly arrived at Haifa, only Revisionist representatives came to greet them. The mainstream leadership and press ignored their rivals’ event, an insult that cut the Revisionists deeply. The same pettiness was visible in the ongoing argument over which movement was the first to land a ship of illegal immigrants. (According to the author, it appears to have been the Revisionists with their ship Kawkab in January 1934.)

The Labor Zionists, for their part, established fishing collectives like Ein Gev on the Kinneret, Sdot Yam on the Mediterranean, and Hulata on Lake Hula. When war with the Arab world began to loom in the 1940s, young members of those communities would go on to play key roles in the naval arms of the military underground, like the Palyam, which would evolve after 1948 into the Israeli navy. Cohen-Hattab describes these and other strands in the story of Zionism at sea—the advent of a holiday called “Sea Day,” for example, and the construction of a club for Jewish seamen at the Haifa port, complete with what every sailor hopes for on shore: wholesome cultural activities and a library.

He recounts the arrival of a crucial group of recruits to the national effort: experienced longshoremen from the great port of Salonica, Greece, which had once been so dominated by Jews that it closed on the Sabbath. We see how, in fits and starts over the three decades of British rule, the Zionist movement grasped the importance of raising Jews with sea legs. Maritime enterprise, Cohen-Hattab writes, had gone from utterly neglected to no less than a “deciding factor” in Israel’s creation. “[A]t its birth,” he writes, “it already had a national shipping company, control over the land’s three active ports, a flourishing fish-farming industry, a nautical training school—and a maritime sensibility that would serve it well in the years to come.” As Zionism’s Maritime Revolution demonstrates, none of this was inevitable. And, as in the story of the Kedmah’s malfunctioning refrigerators and unruly crew, none of it was smooth. But it happened. Only 38 years went by between Ben-Avi’s lament about the failed Zionist fishermen of 1912 to the day in 1950 when President Chaim Weizmann, en route to a vacation in Europe, drove to an Israeli port, walked up the Kedmah’s gangplank, and was greeted by a Hebrew-speaking crew. “It is a pleasure,” Weizmann declared: “a Jewish ship.”

Suggested Reading

An Al Schwimmer Production

When the ancient Spartans sought to aid a friendly state in distress, they did not send troops or arms or money.

Lawfare

What's the trouble with the international laws of war?

A Tale of Two Stories

In their respective new books, Schama and Feiner attempt not to relate the whole history of the Jews during the period covered by their volumes but to tell their story—indeed, to a large extent, to let them tell their story in their own words, culled from their letters, diaries, and autobiographical works.

Spy vs. Spy

Beginning in 1940 the French and the Zionists had a common enemy—the British.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In