Lawfare

In this brisk survey of recent disputes, Peter Berkowitz defends Israel against some of the more outrageous accusations leveled against it. He makes a quite compelling case that Israel was not guilty of violating generally accepted laws of war in 2008, when it sent its army into Gaza to suppress terrorist attacks on civilians in Israel. He also demonstrates that Israel acted consistently with international law in 2010 when it sent its navy to stop the Mavi Marmara and other ships from breaking its blockade of Gaza.

The UN Human Rights Council commissioned the Goldstone Report to investigate “war crimes” by the IDF in “Operation Cast Lead,” Israel’s military campaign against Hamas strongholds in Gaza in the winter of 2008-2009. South African judge Richard Goldstone, who had helped launch the international criminal tribunal for Yugoslavia in the 1990s, lent his name to the inquiry. As Berkowitz recounts, the deck was stacked against Israel from the outset. The committee relied, for the most part, on one-sided accounts supplied by Hamas sympathizers in Gaza and always put the worst construction on Israel’s actual motives.

The report accuses the Israeli armed forces, for instance, of relying on a concept of “supporting infrastructure” that transforms “civilians and civilian objects into legitimate targets.” But as Berkowitz rightly protests, this is a “perverse inversion.” In fact, in Gaza, “the unlawful transformation of civilians and civilian objects into supporting infrastructure for violent jihad against Israel was not a result of Israel’s framing but rather an essential feature of Hamas’ strategy.” Despite Hamas’ worst efforts, Berkowitz shows, Israel did as much as was possible in its 2008 incursion into Gaza to attack legitimate military targets without harming civilians.

In another revealing example, the Goldstone Report contends that Israel’s response to Hamas provocations caused disproportionate harm to innocent civilians in Gaza and was therefore unlawful-indeed, that Israel’s actions reached the level of “war crimes.” But, as Berkowitz argues, it arrived at this conclusion without the required recourse to “factual findings about what commanders and soldiers knew and intended, on complex calculations about tactics and strategy, on the care with which decisions were made, on the prudential steps and precautions taken, and on the propriety of sometimes instant judgments in life and death situations.” The findings of a report that routinely ignored such “legally essential considerations,” Berkowitz correctly concludes, are of no value whatever.

The conclusions of the Goldstone Report were foreordained. Goldstone’s commission from the UN Human Rights Council was framed from the outset as an inquiry into “Israeli war crimes,” with no mention of what Hamas might have done. Goldstone’s investigators were in no position to make factual findings from an inquiry that did not have access to Israeli military records or personnel and could not provide security to Gaza civilians it did interview, who might otherwise have challenged official Hamas claims.

This one-sidedness was entirely consistent with the general orientation of the UN Human Rights Council, as Berkowitz notes.

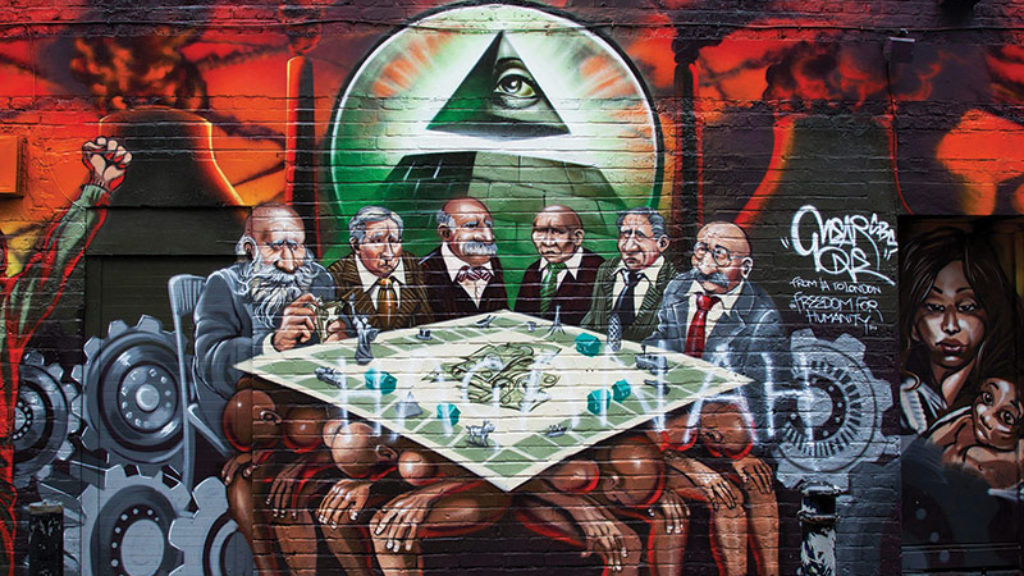

A majority of its members appear to take a cynical view of international law, conceiving of it as a tool for punishing enemies and rewarding friends, and regarding Israel as the most odious of enemies and the principal threat to international order.

No wonder the Council has refused to reconsider its endorsement of the Goldstone Report, even after Goldstone himself publicly retracted its most extreme charge, that Israel deliberately targeted civilians.

While Berkowitz concentrates most of his attention on the flaws in the Goldstone Report, he also devotes a chapter to the dispute about Israel’s interception of the Turkish flotilla. As he explains, frequent denunciations of the Gaza blockade as “illegal” depict it as a violation of humanitarian safeguards in the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention on the treatment of civilians in occupied territory. This argument presumes, however, that Gaza is still a territory “occupied” by Israel—a premise contrary to recent history, common sense, and indeed to legal usage in other conflict zones.

Berkowitz does an admirable job of getting Israel off the hook on which its enemies have tried to place it—but only up to a point. He doesn’t do very much to enlighten his readers about the origins and design of this hook—the contemporary understanding of the “laws of war.” Early on, he refers to the “master concepts of the international laws of war governing combat operations.” One of these, he says, is “the principle of distinction,” which “requires parties to a conflict to distinguish between civilians and civilian objects, and combatants and military objects, and prohibits targeting the former.” The other main principle, according to Berkowitz, is that of proportionality, which “requires that the force used in the pursuit of legitimate military objectives be reasonably expected not to cause harm to civilians or to civilian objects that would be excessive in relation to the anticipated military advantage.” How and when did these restrictions come to undergird the laws of war?

Only in the very last paragraph of the book does Berkowitz acknowledge that these “master concepts” have not always been treated as absolute obligations through the long history of war or even the history of modern war. “In the aftermath of World War II,” he writes, “a great revolution in military affairs brought the conduct of war under vastly greater legal supervision. The revolution has accelerated over the last several decades and continues apace.” Nothing in this book helps readers to understand this claim. Is he referring here to the Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Trials in 1945 and 1946? Is he thinking of the 1949 Geneva Conventions? Is that where we get these basic principles? But in the following decade, the United States began accumulating an arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles with thermonuclear warheads, eventually stockpiling thousands of such missiles. Were we only going to use them on “military objectives”? Did we think that, in the event of an actual nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union, the tens of millions of anticipated civilian casualties would not be “excessive”?

If the “revolution” was a reaction to World War II, it was a long time in coming. Not one of the accused at Nuremberg or Tokyo was prosecuted for bombing civilians, since the Allies were not willing to brand their own tactics as criminal. Nor did the 1949 Geneva Conventions say anything about the principles of distinction and proportionality. The postwar conventions dealt with protections for wounded combatants, shipwrecked combatants, prisoners of war, and civilians in occupied territories. Apart from ambulances and hospital ships, they put no restrictions on targeting in war zones.

These principles do have some roots in humanitarian admonitions expressed in older treaties, starting with the convention on the “law and custom of war” adopted at The Hague Peace Conference in 1899. But the resulting convention described its restrictions as aiming to “diminish the evils of war, as far as military requirements permit”—and was quite clear that many restrictions were therefore conditional on the circumstances of particular conflicts. It was not until 1977 that Berkowitz’s master concepts were set down as universal, absolute obligations, in Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, known as AP I. That treaty had many innovations that have generated continuing controversy.

Additional Protocol I was the first treaty on war to confer prisoner of war protections on guerilla fighters who disguised themselves as civilians. All previous treaties had assumed that combatants who hid among civilians would inevitably force the opposing fighters to fire on actual civilians. But by 1977, the additional protocols approved this concession to the demands of “national liberation” movements, which relied on previously prohibited guerilla tactics. While accommodating guerillas, AP I also sought to restrain the power of more advanced states that might be fighting against them; it set down far more detailed and constraining limits on permissible targets for bombing or artillery attacks than any previous treaty.

AP I also launched another controversial innovation. It was the first treaty to insist that its restrictions remain binding, even against an enemy that did not adhere to them. Previous treaties spoke about obligations of the “contracting parties,” acknowledging that non-adherents could not expect the same protections as those who accepted the agreed restraints. Thus, to cite the textbook example, when Germany used poison gas and attacked neutral shipping early in World War I, Britain and France asserted they would now be under no obligation to heed prewar restrictions on such tactics. Bombing of cities in World War II was justified in the same way—the Germans (and Japanese) started it.

By eliminating traditional notions of reciprocity (and permissible reprisal when reciprocity breaks down), AP I invited precisely the situation that Israel faced in Gaza. Hamas denied any obligation to the restraints set down in AP I, notably those against attacking civilians, who were the main targets of its rocket attacks on Israel, and deliberately placed its weapons, fighters, and command centers in civilian neighborhoods. When Israel tried to demolish Hamas military sites in its incursion into Gaza in December of 2008, Hamas—and much of the world—put all the blame on Israel for the ensuing civilian casualties.

This result was entirely foreseeable. It is one reason why the United States has never ratified AP I—nor, for that matter, has Israel. Britain, France, Germany, Canada, Australia, and a number of other western states have ratified it but only with reservations stipulating that they will not be bound by all the restrictions against an enemy that defies them.

Instead of acknowledging these complications, Berkowitz offers, as grounding for his “master concepts,” the study published by the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) in 2005, Customary International Humanitarian Law. The point of this multi-volume study was to get around awkward gaps in the ratification of AP I by claiming that all its provisions had become binding on all nations as a matter of customary international law. Historically, much international law has been grounded in custom, for instance, rules about the treatment of ambassadors or of neutral ships in wartime. But “customary law” was supposed to emerge from the actual practice of states. Instead, the ICRC grounded its conclusions on mere verbal pronouncements, which it assiduously collected with mindless disregard for context.

To demonstrate the customary status of restrictions on targeting civilians, the ICRC study repeatedly cites statements of Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as if they could vouch for the conduct of armies. It also cites statements from Saddam Hussein and Hafez al-Assad. It even reports a statement from Neville Chamberlain in 1940, affirming that it would be wrong to bomb “civilian objects” in Germany. The study never bothers to consider whether these edifying pronouncements corresponded to the actual practice of these governments.

The ICRC study is at best a compendium of international rhetoric relating to the conduct of war. The United States government formally repudiated it as any sort of authoritative guide to actual state practice.

Focusing on recent conflicts involving Israel, Berkowitz’s book does not alert readers that there are serious, ongoing disputes about what the law of war is and where it applies. U.S. military manuals, for example, insist it is legitimate to target anything that contributes to an enemy’s “war fighting capacity.” Prominent European commentators protest that this standard could be extended to justify attacks on almost any civilian target, since disruptions in the civilian economy could affect “war fighting capacity.”

There were, in fact, many disputes between U.S. commanders and NATO allies about proper targeting in the air war against Serbia in 1999. Some American commanders acknowledged that they hoped that bombing, which “incidentally” hit civilian infrastructure, would undermine civilian support for Slobodan Milosevic. Today, the Obama administration insists that its drone strikes are perfectly consistent with international law—even when directed at clerics or propagandists who seem to play no direct role in military operations—while UN-sponsored studies and many European commentators urge the opposite.

Israel itself takes issue with various restrictions in AP I. During the second intifada, for example, the IDF (with the approval of Israel’s Supreme Court) deliberately knocked down the family homes of suicide bombers. The point was to show future bombers that their families would still pay a price for their attacks. Prominent Israeli legal commentators have argued that states remain within their rights to engage in reprisals—at least against “inanimate civilian objects”—to punish violations of the laws of war with retaliatory strikes. Professor Yoram Dinstein of Tel Aviv University argues in his classic treatise The Conduct of Hostilities Under the Law of International Armed Conflict that the Additional Protocol “is premised on the unreasonable expectation that” when a state is attacked in ways that violate international law, it should “turn the other cheek” to its attackers: “That sounds more like an exercise in theology than in the laws of war.”

It is hardly a coincidence that Additional Protocol I is so often invoked against Israel. The political momentum for this convention actually began with a conference in Iran a few months after Israel’s victory in 1967. The Third World majority there insisted that international human rights had to embrace the laws of war. In 1975, delegates from more than a hundred countries, the majority of them from the Third World, assembled in Geneva to draft additions to the earlier Geneva conventions. Only a few months later, the same Third World majority endorsed the infamous resolution equating Zionism with racism at the UN General Assembly. Among the invited guests at the Geneva drafting conference were representatives of the Palestine Liberation Organization, who expressed full satisfaction with the results.

For centuries, commentators on the laws of war—basing their opinions on actual practice—insisted that the rules governing the conduct of war (jus in bello) must be insulated from disputes about the justice of the cause on either side (jus ad bellum). AP I discarded this formula to give special claims to “people fighting against racist regimes.” Meanwhile, ordinary domestic rebels still could be crushed by almost any tactics that non-“racist” regimes might choose. By 1998, the international conference drafting the treaty for the International Criminal Court (ICC) agreed to language classifying among “war crimes” the policy of allowing civilians to settle in “occupied territory”—a provision aimed directly and seemingly exclusively at Israeli practice in the disputed Palestinian territories.

A dozen years later, as Berkowitz notes, at the very same session of the Human Rights Council that commissioned Goldstone’s inquiry, the Council rejected a proposal to investigate war crimes in Sri Lanka. In the last months of the civil war there, the Sri Lankan government bombed civilian refugees to get at insurgent guerrillas, killing somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000 civilians. This display of indifference was hardly unique. Berkowitz could have mentioned half a dozen other episodes in which civilian casualties in war zones have far exceeded the losses in Gaza (as with Russian bombing in Chechnya) but received scant attention from the UN or the international community.

In practice, what Berkowitz calls the “laws of war” often function as a set of “gotcha” clauses to be invoked against Israel without regard to what other countries do (let alone what Israel’s immediate enemies do in provoking its actions). The government of Israel has, in fact, quietly asserted its right to depart from the ICRC version of the laws of war. But in Berkowitz’s account, the laws of war are essentially sound and the Red Cross a reliable exponent of their requirements.

In this, Berkowitz follows the lead of Israeli government’s rebuttals to the Goldstone Report. The IDF does seem to have gone to great lengths to minimize loss of life and physical injury to civilians, by sending helicopters, for instance, over buildings that were going to be attacked to give an advance “knock”—a warning to civilians to leave. But Berkowitz expresses indignation at claims in the Goldstone Report that Israel intended to cause harm to civilian infrastructure to “demoralize civilians.” That would not, in fact, be at odds with past IDF practice. It would be consistent with a blockade that—while always allowing food and medical supplies to reach civilians—did try to impose economic hardship evidently with the aim of undermining support for Hamas among the civil population in Gaza. But since the Israeli government insists that it does respect the laws of war, Berkowitz presents it as complying even with the Red Cross version.

Why don’t defenders of Israeli policies—why doesn’t the government of Israel itself—offer more forthright challenges to the unreasonable expectations now associated with the laws of war? One reason, surely, is that Israel wants to present itself as always acting lawfully. It wouldn’t help its case to advertise its objections to the law. Even the United States government began by insisting that detention of suspected terrorists at Guantanamo was entirely lawful, then wound up promising (as early as George Bush’s second term) to work toward closing down that facility. Israel has more reason to be sensitive to criticism, particularly in Europe.

These issues are not just a matter of public relations. A number of European countries still have legal provisions authorizing national prosecutors to exercise “universal jurisdiction” against the most serious crimes—war crimes or crimes against humanity—if they cannot be addressed elsewhere. Earlier this year, the ICC rejected a long-standing Palestinian effort to have the court’s prosecutor investigate Israeli tactics in the Gaza campaign on the grounds that Palestine is not a state. In 2009, a UK magistrate issued a warrant for the arrest of Tzipi Livni, forcing her to cancel a diplomatic trip to London for fear she would actually be put on trial while there. The possibility remains, however, that the ICC will decide that it does, after all, have jurisdiction over Israeli attacks on the Palestinians or a neighboring state. But the ICC, too, is supposed to defer to national authorities when they are investigating in good faith. If Israel were to highlight its disagreements with particular international standards, it would not help its claim that it can be trusted to investigate its own military actions.

But there’s more to it than legal strategy. At a deeper level, the IDF clearly seeks to reassure itself that it is acting properly, decently, lawfully-maintaining the “purity” of its “weapons,” by not engaging in unrestrained violence. I have met quite a few American military specialists who concede (at least in private) that international legal standards are sometimes just a nuisance to get around. By contrast, I’ve never met an Israeli analyst who does not express serious concern about establishing proper limits on force. The IDF submits to lawsuits in which the Israeli Supreme Court weighs the legality of particular targeting decisions, sometimes even in the midst of ongoing military operations.

The Israeli Supreme Court says, in turn, that democracies must fight with restraint but it does not, in fact, defer to the actual practice of other democracies. It sets its own standard, often more restrictive than that displayed in American combat operations (if more permissive than those found in European military manuals). I am not sure how many Israelis accept such restraints as a matter of democratic theory, but there does seem to be widespread acceptance that a Jewish state cannot sink to the barbarism of its enemies.

Nonetheless, war imposes harsh discipline. When enemies attack, the defense must adapt to the nature of the attack rather than the ideals of third parties. Israel can’t simply conduct its wars as Red Cross lawyers in Geneva might think most proper. Israel has much reason to scoff at international law, which so often seems to amount to edifying admonitions with little claim on anyone—except when Israel’s enemies invoke it with determined malice and its fair-weather friends invoke it with utopian fantasy. It is entitled to scoff at the advice it receives from nations that do not face constant serious security threats and probably could not deal with them if they did.

It is, in a way, a tribute to Israel that its defenders don’t scoff. They want to see Israel—as it wants to see itself—as struggling to conform to lawful restraints in its conduct of war. Israel gropes for a law that it can actually treat as law, even if it turns out to be its own law rather than an impractical set of ideals, universally lauded in speech and routinely disregarded in practice. This attitude towards law is much older than Zionism. Israel’s friends should be prepared to view the resulting strains with some patience and respect. The story does not need to be sugarcoated.

Suggested Reading

Kashrut and Kugel: Franz Rosenzweig’s “The Builders”

In 1923, Franz Rosenzweig wrote an open letter to Martin Buber on being bound by Jewish law in the modern age. Interestingly, he was just as concerned with minhag (custom) as halakha.

Saladin, a Knight, and a Jew Walk Onto a Stage

Outside of Germany, Nathan the Wise is one of those works more often read than performed, and more often read about than actually read.

Jews Not without Money

Jews, Money, Myth, at London's Jewish Museum, normalizes the Jewish relationship with money without negating those factors that made this particular historical association especially fraught.

The Jewish Preview of Books—September 2018

A quick look at Jewish books being published this month.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In