Thoreau and the Jewish Problem

One evening a week, I stroll to Old Katamon to learn with my havruta, a jazz musician, student of Kabbalah, and fellow New York émigré. He and I devoted a year to reading aloud Spinoza’s Theological-Political Treatise, line by line like a blatt Gemara, struck repeatedly by its relevance to our lives in Jerusalem. Next, we did King Lear and poems by Robert Lowell, and now we’re deep in the woods of Walden.

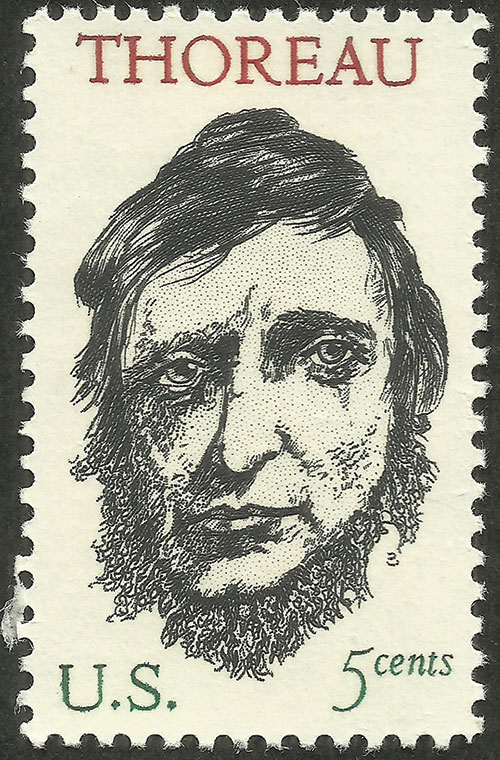

Walden is many things for many people. Nature, self-reliance, wisdom literature. It’s the American Kohelet, Ecclesiastes in Massachusetts. I first read it through in 1985, when I took a semester off from Hollywood to teach history in Texas and assigned it in a seminar called “Art versus Commerce in American Culture.” The students dug Thoreau; who doesn’t? A year later, I decided to move to Israel. Rereading it now reminds me of why I did: “If a man does not keep pace with his companions,” Henry David Thoreau famously writes, “perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.” My havruta and I are stunned by the author’s flashes of poetic insight; we savor the tale, focusing less on the teller. For us, the Walden chapter called “Reading” evokes the spirit of traditional Jewish learning:

To read well, that is, to read true books in a true spirit, is a noble exercise. . . . How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book. The book exists for us perchance which will explain our miracles and reveal new ones. The at present unutterable things we may find somewhere uttered. These same questions that disturb and puzzle and confound us have in their turn occurred to all the wise men; not one has been omitted; and each has answered them, according to his ability, by his words and his life.

When my friend and I read Walden, I shuttle between my old paperback, festooned with underlining and marginalia, and Jeffrey S. Cramer’s handsome annotated edition. The text is flanked vertically with commentary, like Rashi and Tosafot on a page of Talmud. To clarify a passage in “Reading” about poetry, astronomy, and astrology, Cramer quotes Thoreau’s journal from 1853:

Though observatories are multiplied, the heavens receive very little attention. The naked eye may easily see farther than the armed. It depends on who looks through it. . . . The poet’s eye in a fine frenzy rolling ranged from earth to heaven, but this the astronomer’s does not often do. It does not see far beyond the dome of the observatory.

One hears echoes of the songs of Whitman and Psalm 19: “The heavens declare the glory of God, the sky proclaims his handiwork. Day to day makes utterance, night to night speaks out.” But Thoreau was not inclined to quote the Old Testament, not even the King James Version. He was more fond of Hindu, Persian, and Chinese sources, pointedly remarking in Walden: “Most men are satisfied if they read or hear read, and perchance have been convicted by the wisdom of one good book, the Bible. . . . Most men do not know that any nation but the Hebrews have had a scripture.” That’s the transcendentalist speaking, breaking the chains of Puritan Hebraism.

Walden is a novel of sorts, the compression of a two-year stay at Walden Pond into the yearlong narrative of a literary persona called Henry David Thoreau. Americans typically valorize this iconic character—a man of high principles, living off the land, independent and free, in a tiny cabin built with his own hands. But not all admirers have actually read the book, and not all readers are admirers. A few years back, in a scathing New Yorker piece called “Pond Scum,” the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Kathryn Schulz took a relentless hatchet to Walden:

The real Thoreau was, in the fullest sense of the word, self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self-control, adamant that he required nothing beyond himself to understand and thrive in the world. . . . “Walden” is less a cornerstone work of environmental literature than the original cabin porn: a fantasy about rustic life divorced from the reality of living in the woods, and, especially, a fantasy about escaping the entanglements and responsibilities of living among other people.

As an “excellent corrective,” Schulz in all seriousness recommended the oeuvre of Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of Little House on the Prairie, which I frankly can’t imagine reading in havruta. Yet a fair question persists: We love Thoreau, but was he likable? He entered Harvard (class of 1837) at age 16, a village boy from Concord among blue bloods from Boston. He studied classics and English poetry along with math and science, seeding his future career as a naturalist and professional surveyor. According to Laura Dassow Walls’s recent biography, he graduated with a reading knowledge of Greek, Latin, French, and German, as well as a “smattering” of Spanish and Italian. Over the years, the man who was baptized David Henry (he reversed the order in college) has acquired a reputation—unwarranted in Walls’s view—as something of a misanthrope. This impression derives in large part from an article that appeared in the Christian Examiner in July 1865, three years after Thoreau’s death from tuberculosis at age 44. It was written by a classmate whose name was John Weiss.

Many writers have mined this account of the young Thoreau. His biographer of 1939, Henry Seidel Canby, called it a “pen picture of Thoreau at Harvard which could hardly be bettered.” Of its author, he wrote that John Weiss “had a beard and burning eyes. Later he made a reputation as a Unitarian minister and an outspoken antagonist of slavery, was a wit, an explosive intellect, and a man untouched by conventions.” Weiss began his portrait by admitting that he didn’t know his classmate well—“We did not suspect the fine genius that was developing under that impassive demeanor”—launching nonetheless into an extensive description of his personality:

He was cold and unimpressible. The touch of his hand was moist and indifferent. . . . How the prominent, gray-blue eyes seemed to rove down the path, just in advance of his feet, as his grave Indian stride carried him down to University Hall! . . . He did not care for people; his classmates seemed very remote. This reverie hung always about him. . . . Thought had not yet awakened his countenance; it was serene, but rather dull, rather plodding. The lips were not yet firm; there was almost a look of smug satisfaction lurking round their corners. It is plain now that he was preparing to hold his future views with great setness, and personal appreciation of their importance. The nose was prominent, but its curve fell forward without firmness over the upper lip; and we remember him as looking very much like some Egyptian sculptures of faces, large-featured, but brooding, immobile, fixed in a mystic egotism.

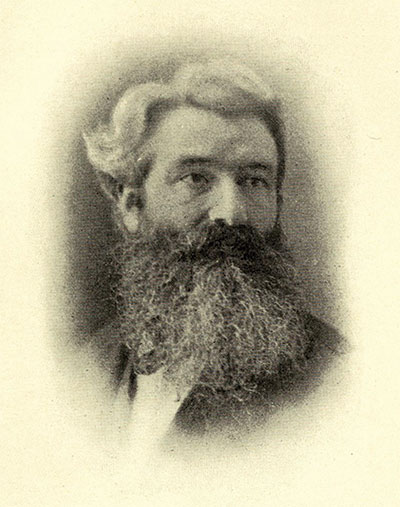

photograph from 1845.

In the same long essay, Weiss wrote that “no writer of the present day is more religious” than Thoreau. “His spiritual life was not deficient in soundness because it stood unrelated to conventional names and observances.” One suspects that Weiss was justifying his own iconoclastic identity. John Weiss, in a photo, looks like an Ellis Island ancestor or the Hasid beside me on a Jerusalem bus, his nose in a holy book—which comes as no surprise because he was Jewish, at least by birth.

The Unitarian minister Octavius Brooks Frothingham, in my grad school copy of his Transcendentalism in New England,thought the world of his colleague John Weiss: “Supremely intellectual, capable of treading, with steady step, the hair lines of thought. . . . His method is peculiar to himself; his is not the exulting mood of Emerson . . . it is purely poetic, imaginative. The doctrine of the divine immanence is glorious in his eyes.” For Frothingham, nothing about Weiss was Jewish, but that doctrine of divine immanence reminds me of the psalmist and Spinoza. (Call me irreverent, but I can’t pronounce the name Octavius B. Frothingham without thinking of Groucho Marx in Horse Feathers.)

In his 1936 classic, Three Centuries of Harvard, the wellborn historian Samuel Eliot Morison invoked Weiss the Jew to illustrate tolerance on campus while contrasting his sociability with Thoreau’s solitariness.

It is difficult to see how any student of this period, unless invincibly unsocial in temperament and tastes, could have been wholly unclubbed. Lack of money or social background was no bar. John Weiss (A.B. 1837), the future Transcendentalist, son of a Jewish barber of Worcester, belonged in College to the Institute of 1770, the Phi Beta Kappa, and the Hasty Pudding, of which he was secretary and poet. His classmate Henry Thoreau, on the other hand, belonged only to the Natural History Society.

Three years later, Henry Seidel Canby identified Weiss as “the grandson of a German Jew of Germantown, Pennsylvania, and probably himself a little uncomfortable in the Harvard Zion.” Did Thoreau perceive Weiss as a fellow outsider? Did Weiss project his Jewish otherness onto Thoreau in that influential pen portrait?

In her 1986 exhibition catalog The Jewish Experience at Harvard and Radcliffe, Nitza Rosovsky flatly stated that “John Weiss, who graduated in 1837, is often referred to as a Jew but can hardly be considered one.” His grandfather, also named John, was a “political exile” who “kept a tavern” in Germantown. “It seems that by the time John was born in 1818, the family was no longer Jewish.” At Harvard, “he was often admonished for skipping prayer services—a common practice—yet was considered witty and filled with religious idealism.” Witty, heretical? Sounds to me like the class Jew.

At this point, I stop and ask myself, so what? Who cares if Thoreau’s obscure classmate was the son or grandson of a Jewish barber or bartender? Am I engaging in parochial antiquarianism or, heaven help me, the subgenre of Jewish journalism that reveals the “secret Jewish history of Beyoncé”? Am I guilty of the syndrome known as “elephants and the Jewish Problem”? Indeed, the Jewish Problem par excellence is the inability to see anything except through Jewish glasses: hereditary astigmatism and occupational hazard.

Still, I wonder: Was a vestige of the Jewish Problem stuck inside John Weiss, like shrapnel? Let’s try to read Thoreau’s classmate more closely. He was an admiring biographer of his fellow transcendentalist-abolitionist Theodore Parker and translator into English of Friedrich Schiller’s Philosophical and Aesthetic Letters and Essays. His book American Religion is a summa of his Unitarian thinking. A better bet is Wit, Humor, and Shakespeare: Twelve Essays.If an illuminating spark of Jewishness was buried in the soul of John Weiss, it would surely be in such a book. A search in the online facsimile produces a pair of fine specimens. The first, from the essay called “Wit, Irony, Humor”:

Two Jews have been elected within a few years to be Lord Mayors of London. They were members of the synagogue in full connection, and might have appointed Rabbins for chaplaincies if they had chosen. But they pursued the old custom, which was not however of legal stringency: appointed clergymen of the Church of England, and regularly made all the usual contributions for Christian purposes, including the customary one to the Society for the Conversion of the Jews. In this incident it is the element of Humor which imparts to us the pleasure we feel.

Not to mention the pleasure of an inside joke: a Unitarian of Jewish ancestry trying his hand at Jewish humor. Better he should have told this one:

Two former yeshiva bochurs meet by chance in town. One has converted and become a priest. The other is aghast. “Moishe, you were always the smartest; now look at you. It’s a shandeh—is there not one bit of Torah left in you?” To which Moishe replies, “Yankele, relax. I’m still afraid of dogs.”

Analogously, in Weiss’s book on Shakespearean humor, the only occurrence of the adjective “Jewish” is not about Shylock but rather the gravediggers’ scene in Hamlet. In a footnote on the “Dance of Death, or the so-called Danse Macabre,” Weiss exhumed a grim theory:

One interpretation of this word gives it a Jewish origin, and makes of it the Dance of the Maccabees, established to commemorate the martyrdom of the seven brothers of the Maccabees, together with Eleazar and their mother. . . . This was imitated by a solemn dance of priests and civil authorities, who went out in turn and disappeared as if to death.

Taken together, these Jewish snippets suggest nervous anxiety, shpilkes. In the well-turned words of Octavius B. Frothingham, this is “not the exulting mood of Emerson.”

Before entering Harvard Divinity School, Weiss studied German philosophy at Heidelberg University. While serving as a young pastor in Watertown, Massachusetts, he wrote the glowing introduction to the American edition of a biography of Johann Gottlieb Fichte, the idealist philosopher who bridged Kant and Hegel. The baptized Heinrich Heine, paragon of Jewish wit, boiled Fichte’s philosophy down:

Thought is supposed to eavesdrop on itself as it thinks, as it slowly becomes warm and warmer and is finally cooked through. This reminds us of the ape who sits at the stove in front of a copper pot and cooks its own tail. . . . The satire which Fichtean philosophy has always had to endure is its own story.

For Weiss, Fichte was a heroic figure: “He was knowledge, and he was power: he thought the subtlest thoughts into deeds: he condensed that German gas.” In retrospect, not the best metaphor for “subtlest thoughts.” Yes, I confess to shameless cherry-picking and cheap foreshadowing, but a gnawing question remains: What did John Weiss make of the antisemitic winds blowing in Germany? Did he know, or take personally, what Fichte had notoriously written in 1793 regarding the Jews:

[A]s to giving them civil rights, I see no way other than that of some night cutting off all their heads, and attaching in their stead others in which there is not a single Jewish idea. To protect ourselves against them I again see no way other than that of conquering for them their promised land and of sending them all to it.

When John Weiss died in 1879, his private library was offered to the public by Leonard & Co., Boston auctioneers. The auction catalog may be found at Harvard’s Houghton Library, where I waded through more than a thousand book titles, panning for grains of Jewish interest. Two caught my eye: History of the Israelitish Nation: From Abraham to the Present Time (two volumes), by the American reform rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, and The Bible, the Koran, and the Talmud: Or, Biblical Legends of the Mussulmans, by the German orientalist Gustav Weil, grandson of a rabbi and librarian of Heidelberg University when John Weiss was a student there. Did he read either of these books? In the preface to his first volume, Wise wrote:

The nations of antiquity rolled away in the current of ages, Israel alone remained an indestructible edifice of gray antiquity, inscribed with the enigmatical characters of the distant history of primitive ages, and preserved by an internal and marvelous power. . . . The unshaken and unexceptionable confidence in God characterizing this people; the boldness and divine inspiration of their prophets, orators, sages and martyrs, who advocated and expounded this leading idea, and frequently confirmed it by their own lives; the indestructibility of their nationality and the unyielding fortitude with which they adhered to their religion, are the next consequences of that sublime consciousness.

If the Reverend Weiss read these stirring words of Rabbi Wise, did he feel a frisson of Jewish pride? Or a vague chill of insecurity? Did John Weiss have a Jewish problem or see himself as no more Jewish than Octavius B. Frothingham or Henry David Thoreau?

Simplify, simplify: Thoreau’s famous dictum rings out like a bat-kol—a heavenly voice—in our confused and polarized world. In Old Katamon, a Jewish musician sits in his cozy home studio with his havruta, slowly reciting an apposite riff from the Walden chapter “Sounds”:

Sometimes, on Sundays, I heard the bells, the Lincoln, Acton, Bedford, or Concord bell, when the wind was favorable, a faint, sweet, and, as it were, natural melody, worth importing into the wilderness. At a sufficient distance over the woods this sound acquires a certain vibratory hum, as if the pine needles in the horizon were the strings of a harp which it swept. All sound heard at the greatest possible distance produces one and the same effect, a vibration of the universal lyre, just as the intervening atmosphere makes a distant ridge of earth interesting to our eyes by the azure tint it imparts to it. There came to me in this case a melody which the air had strained, and which had conversed with every leaf and needle of the wood, that portion of the sound which the elements had taken up and modulated and echoed from vale to vale. The echo is, to some extent, an original sound, and therein is the magic and charm of it. It is not merely a repetition of what was worth repeating in the bell, but partly the voice of the wood; the same trivial words and notes sung by a wood-nymph.

The elegant “vibration of the universal lyre” harmonizes with a previous passage in Walden:

Men esteem truth remote, in the outskirts of the system, behind the farthest star, before Adam and after the last man. In eternity there is indeed something true and sublime. But all these times and places and occasions are now and here. God Himself culminates in the present moment, and will never be more divine in the lapse of all the ages. And we are enabled to apprehend at all what is sublime and noble only by the perpetual instilling and drenching of the reality that surrounds us.

Now and here. A Jewish gloss on Walden might recall the talmudic tale known as “The Oven of Akhnai.” Thoreau’s masterpiece is stuffed with details—birds and beans, trees and trains—that both embody and eclipse the spiritual essence of his book. The convoluted story in Bava Metzia concerns halakhic minutiae pertaining to the kashrut of a tiled oven and various miracles allegedly supporting the position of Rabbi Eliezer. The oft-quoted punchline, lo bashamayim hi—“it is not in heaven”—also teaches us that religious wisdom is to be found in this world. Week after week, I walk home from Old Katamon pondering such sweet correspondences and wondering what the universalist preacher John Weiss might say, if he could still read a blatt Gemara.

Suggested Reading

The Lowells and the Jews

Robert Lowell, the most famous poet in America, icon of the antiwar movement, consummate Boston Brahmin, was especially glad to speak with a Jewish group because, he drawled, “I’m an eighth, you know.”

Walkers in the City

Herman Melville was unimpressed with Jerusalem in 1857, but what would he say if he were a saunterer on Mamilla or King George today?

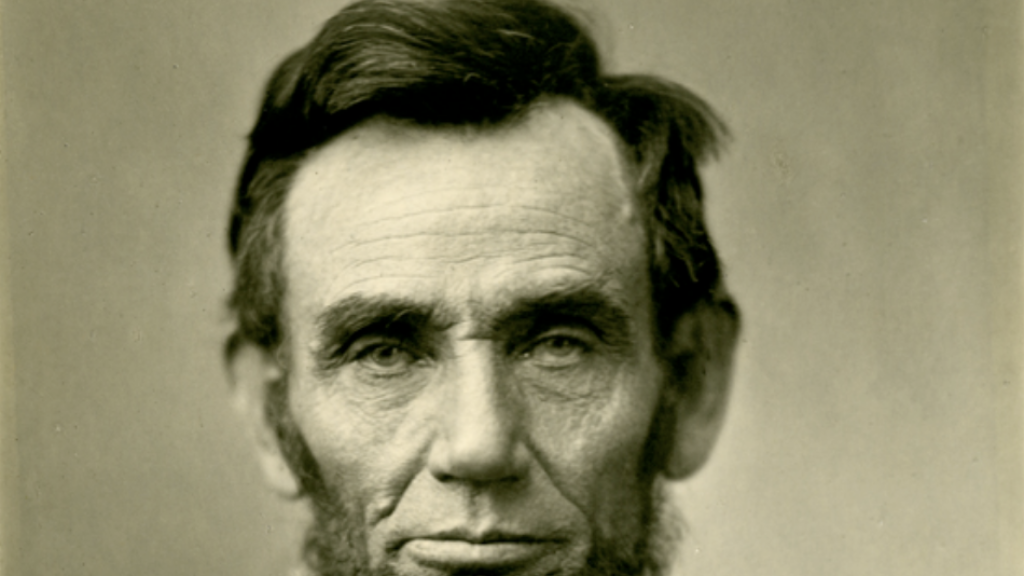

Was Lincoln Jewish?

Abraham Lincoln became a saint for American Jews. But was he also "bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh"? One rabbi thought so.

A Pinch of Levity

Is it true that three people are required to perfect a joke: one to tell it, one to get it, and a third not to get it? Stuart Schoffman tracks a single Jewish joke through multiple tellings.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In