A Pinch of Levity

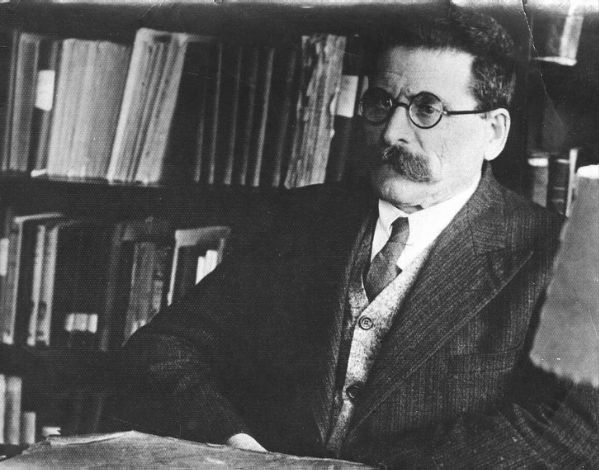

What’s your favorite Jewish joke? Mine is drawn from the three-volume Hebrew classic Sefer ha-bedicha ve-hachidud (The Book of Jokes and Wit), compiled by Alter Druyanov (1870–1938), a Russian Jew. He was a staunch Zionist who made aliyah, twice. The first try was in 1906, the same year as Ben-Gurion, but after three years Druyanov returned to Vilna to edit the Hebrew Zionist newspaper Ha-olam. He then gravitated to Odessa, a lively haven for Jewish writers, and was part of the circle that included Chaim Nachman Bialik and other Hebraists who told their jokes in Yiddish. Like Bialik and Y. H. Ravnitzky, coeditors of the indispensable Sefer ha-agada (The Book of Legends), Druyanov was a folklorist. He collected thousands of Jewish jokes and translated them into Hebrew. He moved back to Palestine in 1921 and the following year, in Tel Aviv, published his compendium, meticulously organized by category.

Druyanov’s magnum opus is not a treasure chest of thigh-slappers. The jokes are often unfunny and dated, but a few hold up very well. The one I find myself coming back to is Joke no. 2081, in the “Jews among the Nations” section of volume 2:

A question was put to Alexander Moszkowski the mumar [converted Jew]: “You, who are both a goy and a Jew, maybe you know the difference between them?” Answered Moszkowski: “Of course I know. When a Gentile is thirsty, he takes three drinks one after the other; when a Jew is thirsty, he checks his blood sugar.”

A meme, a trope, too often a fact of life in Druyanov’s world. The Gentile as violent drunkard, the Jew as hypochondriac, expecting the worst. Moszkowski, the aforementioned mumar, was a well-known German satirist “of Polish-Jewish descent,” in the words of Wikipedia, possibly remembered as the author of the first biography of Albert Einstein, published in 1921. He had a younger brother named Moritz, a brilliant musician who at age 19 performed a double piano concerto with Franz Liszt. Druyanov immortalized him too, in a section called“Apostates and Informers.” But as we learn from Joke no. 1444, Moritz was no mumar:

The famous pianist Moritz Moszkowski was asked: “Why did you not go the way of your family, all of whom converted [hemiru], and you stayed Jewish?” Replied Moszkowski: “Lehamir? No, it’s too Jewish a minhag” [a custom, a way of life].

It’s also a double entendre: hamarat dat means conversion; hamarat kesef means money-changing. Druyanov is chock-a-block with such inside jokes, intelligible mainly to Jews.

In late summer, as rabbis prepare their High Holiday sermons, let us keep in mind a crucial talmudic teaching (Pesachim, 117a): “Rabbah used to say something humorous [milta debedichuta] to the other rabbis before he began his lesson, in order to amuse them.” Ergo, the best Jewish jokes are ones that both entertain and educate. Case in point, Druyanov’s no. 2081, modernized for maximum effect. I bet you’ve heard it:

The Frenchman says, “I am tired and thirsty; I must have wine.”

The German says, “I am tired and thirsty; I must have beer.”

And the Jew says, “I am tired and thirsty; I must have diabetes.”

Engraved deep in our DNA is the bira amikta of historical hypochondria, a bottomless well of justifiable paranoia. Wherever you go, wherever you’re from, Amalek is out to get you. I told this joke countless times during the years I rode the Jewish lecture circuit in the Old Country. The punch line always got a great laugh. (Hat tip to the audience of Jewish doctors in Seattle for the biggest laugh ever.) But then there was the time, in the winter of 2005, the waning days of the Second Intifada, when I was invited by a Jesuit friend to speak to a group of Roman Catholic bishops from around the world in the Christian Quarter of Jerusalem. The subject was “the Situation.” The other speaker would be a Palestinian intellectual. The bishops were interested in hearing both sides.

On the appointed day I set out on foot for the Old City, wondering how to handle my talk. Might I dare a pinch of levity? I was a veteran of many interfaith encounters and activities. But a roomful of bishops? Before I left the house, my teenage son had said to me, Abba, if you’re going to be the only Jew in the room, you should wear a kippah. I thought it over and decided he was right. I entered the Jaffa Gate, turned left on Latin Patriarchate Road, and arrived at the Knights Palace Hotel, where the bishops were already seated. I was the only Jew in the room, but not the only kippah.

We were fellow men of faith. I went for it . . . I must have diabetes. The few extra milliseconds it took them to laugh heartily were the longest of my career as an itinerant tummler. Did they get it? Take it the wrong way? I carefully explained the joke’s relevance to our topic: Israelis are perceived as powerful, but considering our traumatic history as Jews, we have a lingering strain of insecurity. To understand the political situation, one must try to understand the mentalities of both cultures. I’m here to talk about the Jews. I cannot presume to talk about the mentality of others. The bishops, if memory serves, nodded their assent.

I went on to present my bona fides as an empathetic Jew devoted to the Jewish people as well as human rights. I quoted Exodus 23:9, a verse presumably known to the bishops: The Jewish people “know the feelings of the stranger,” for we were strangers in Egypt; and we are commanded by the Torah, fully 36 times, not to oppress the stranger. For good measure, I threw in Martin Buber and Rabbi Judah Magnes and Brit Shalom, who dreamed in Mandatory Palestine of Jewish-Arab symbiosis. I am not naive, I assured the assembled, about rising anti-Semitism and the existential threats facing Israel, but I am hopeful for the future; and then I sat down. The other speaker, the chairman of a Palestinian academic society, was listed as first on the program but had asked to go second, utilizing the advantage of rebuttal to drive home the Palestinian case. Departing from his prepared text, he began: “I am tired and thirsty, but they will not let me have water . . .”

Ah yes, heavy sigh, no good joke goes unpunished. The learned gentleman went on and on about the Occupation (“We are in a prison”), the “three Gs” (“gates, guards, and guns”), and the newly erected Israeli security barrier or “wall,” which he likened to “a sharp knife cutting our flesh and sucking our blood.” “We must awaken the Jewish conscience,” he declared, as if I had not just dwelt at length on the Jewish obligation to remedy the suffering of the Palestinians. “Your pressure,” he sternly told the bishops, “is very much needed.”

Now came closing remarks. Mixing my metaphors, I voiced optimism that both sides could together envision a thirst-quenching water glass that is at least half full. If the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not yet curable, it is treatable, like diabetes. But my adversary wasn’t buying. He dismissed my sermonizing and demanded historic justice. A Palestinian woman, standing in the back of the hall, angrily raised her hand: “I am not the stranger. You are the stranger. You come from America and I have been here from time immemorial.” I tried fruitlessly to clarify that we are strangers to each other, fated to inhabit the same small ancestral homeland. Afterward, my Jesuit friend told me I had done well overall, but next time, “Drop Exodus 23:9. Palestinians hate that verse.”

Fifteen years have gone by, and “the Situation” is much the same. Revisiting this episode, it dawns on me: A bishop from Italy or Uruguay would have likely viewed my knitted skullcap and his own purple one as divergent fashion statements. But a Palestinian from Jerusalem, Muslim or Christian, could have easily misread my seldom-worn kippah as a badge of Israeli colonialism. Then again, had I been bareheaded, my message would have probably rung hollow too. For the record, I’m still a big fan of Buber and Judah Magnes, and I still love that fabulous old diabetes joke. But these days, I tell it more selectively.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

War & Peace & Judaism

Robert Eisen was walking to campus on 9/11 when he saw a dark cloud above the Pentagon. Alick Isaacs fought for the IDF in Lebanon. Their experiences prompted them to rethink peace and Judaism.

Eight Families and the 18 Percent

Whether it’s 18 percent or eight families, Gordon Tucker maintains “patience and tenaciousness change the world,” a fact that is lost when we focus on numbers.

Love and War

David Grossman has for sometime been one of Israel's most talented and important writers. In many of his novels, his feeling for adolescence—one is tempted to say, his identification with it—has been so brilliantly intuitive that the imagining of adulthood has scarcely been possible. In To the End of the Land, Grossman makes his breakthrough.

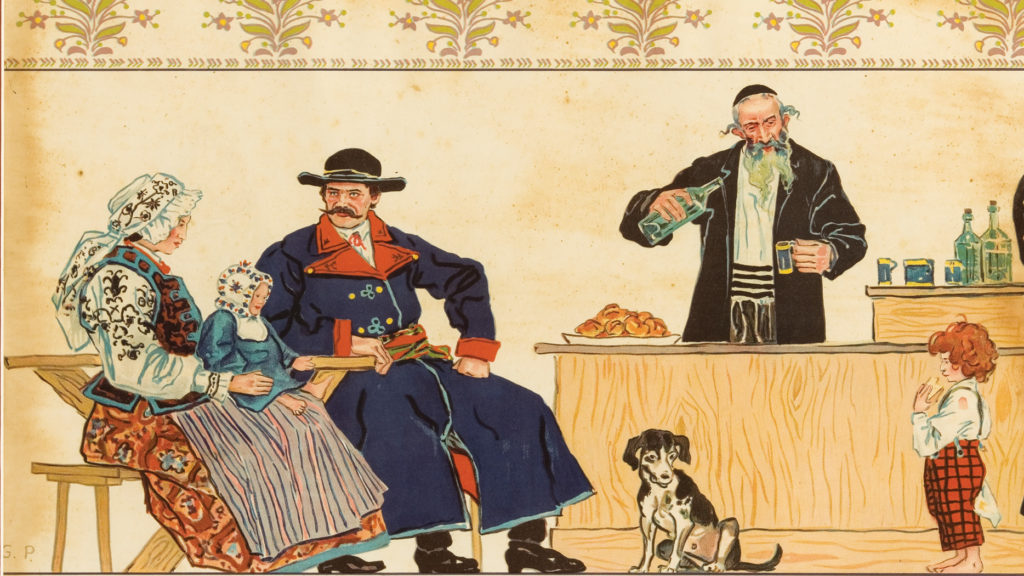

Poland’s Jewish Problem: Vodka?

Jewish-run taverns—rowdy, often very seedy drink-holes—served to cement, rather than sour, the impossibly tense and intertwined lives of Poles and Jews, as a new book by Glenn Dynner shows.

Eric Bruskin

There is a factual response to the woman who said “I am not the stranger. You are the stranger. You come from America and I have been here from time immemorial.” She has not been there forever, she was born a human being just like you. If she's referring to her ancestors, then your ancestors have an equal and perhaps prior claim to that land. You were driven out in 70CE, and then actively kept out by every occupying power since then - Rome, the Ottomans, the Brits. The evidence of your desire to return is in writing in countless manuscripts and books since then. It's not your fault you're just coming back now. But your claim is at least equal to hers. I wish you'd been able to say that at the time.

Or am I wrong?

Rachel Freilich

A wonderful rational response from Eric, and yes you are right.

Linda Abraham

My favorite joke represents the Jews' perpetual naivete, optimism, and penchant to automatically think the best of anyone: "A Jew, newly arrived in America from Europe (a greenhorn) takes a walk in the park on the Sabbath, and sees a man smoking a fat cigar and reading a Yiddish newspaper. He exclaims, "America, what a country! Even the goyim know Yiddish!"