Begin’s Shakespeare

The restoration of Jewish national sovereignty and the survival of the State of Israel in its first decades required extraordinary leaders. Even after the final departure from office of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, the country remained in great need of statesmen with a clear understanding of the opportunities available to them—as well as the limitations on their actions—in a highly complex political environment. Yehuda Avner’s memoir examines the striking personalities and accomplishments of some of Israel’s first leaders, and illustrates them in vivid detail. Avner’s presence on the scene as a speech writer, senior advisor, and confidant for four of Israel’s prime ministers—Eshkol, Meir, Rabin, and Begin—provided him with a ringside view of the action. Like Dean Acheson’s Present at the Creation, a classic memoir of the origins of the Cold War as seen from the top floor of the US State Department, Avner’s The Prime Ministers is an indispensable book. It is required reading for understanding the formative years of Israeli foreign policy and diplomacy.

In 1947, while still in his teens, the idealistic young Avner left his family in Manchester to settle in Palestine. As one of the founders of the religious Kibbutz Lavi, he “harvested rocks” to clear the land, dug latrines, and took up arms in Israel’s War of Independence. In 1959, Avner was hired as a “greenhorn” translator in the foreign ministry over which Golda Meir presided, and at the height of Ben-Gurion’s dominance of Israeli politics. Although he was not a member of the Labor party, his intellect and skills compensated for the lack of political allegiance usually necessary for promotion. In 1963, he became an English-language speechwriter for Eshkol, who became prime minister after Ben-Gurion’s abrupt resignation. When Eshkol and his successors traveled abroad, Avner was also their note-taker and confidant. He eventually became a senior advisor and, at the peak of his career, ambassador to Britain and Australia.

In contrast to revisionist and polemical biographies, Avner’s memoir includes little speculative psychological or political analysis, and reflects respect and affection for the prime ministers who led the country during this period. As he emphasizes, all four of the leaders for whom he worked were fully dedicated to the objectives of Zionism and to their public responsibilities. None could even be suspected of abusing the power and public trust for personal gain. Although each leader featured in this volume had his or her distinctive view of the international and regional environment and the policy options available to Israel, they all shared a hard-core realism. They understood that in international politics, power and interests, rather than ideals or moral commitments, usually determined policy, and expected little in the way of benevolence from the “international community.” Outflanked by Arab oil power, Israel needed to tread carefully, find allies where possible, and minimize the dangers when out-gunned diplomatically.

The fragility of Israel’s position is reflected in the story Avner tells about a speech he drafted for Eshkol at the time of his 1965 state visit to London. When the young advisor sought to “rebrand Israel” (using today’s foreign ministry jargon) as a normal country, including references to cultural pluralism and “Tel Aviv high jinks,” Eshkol rejected the draft, and scolded him: “Don’t you understand we are still at war? We are still beleaguered. We still face terrorism . . . We are still absorbing hundreds of thousands of refugee immigrants. So how on earth can you expect us to be normal?”

This admonition notwithstanding, Eshkol himself had little difficulty reverting to normality, even while engaging in diplomacy on the highest level. Three years after his state visit to the capital of the United Kingdom, the prime minister and some of his advisers traveled to meet with President Lyndon Johnson at his ranch in south Texas. Johnson packed the group into his station wagon soon after their arrival and sped them around the vast property. “That’s Daisy,” the president announced, pointing to one of his favorite cows, in the midst of a wild ride. Eshkol “looked inquiringly at Dr. Herzog, and above the growl of the engine, asked ‘Vas rett der goy?‘—Yiddish for ‘What’s the goy talking about?'” But when they stopped at a barn to take a closer look at a cow named Nellie, Eshkol, the ex-kibbutznik, was perfectly prepared to enter a stall and crouch down “to examine the cow and her wet and wobbly calf.”

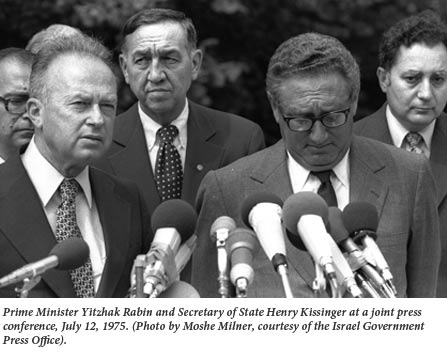

In 1969, shortly after Eshkol’s death, Avner received a call from Israel’s new ambassador to the United States, Yitzhak Rabin, who was looking for someone whose knowledge of English could make up for the deficiencies of his own. Avner spent the next three and a half years at the side of this future prime minister, with whom he was to work directly, once again, after he succeeded Golda Meir in 1974. Rabin, Avner tells us, was “a conceptualizer with a highly structured and analytical mind.” He put these talents on display in 1975 while playing a complex diplomatic and psychological game with Henry Kissinger. At one point in the course of their negotiations, Avner reports, Rabin rebuked the American secretary of state for blaming Israel and not “Sadat’s intransigence” for placing the success of his mission in grave danger. When Rabin characterized Kissinger’s analysis as a “total distortion of the facts,” Kissinger “turned, and without another word walked out of the room,” and brought heavy pressure to bear on Israel. As Avner shows, Rabin then continued to resist Kissinger’s demands for premature concessions and skillfully turned a weak hand into long-term American commitments.

Avner devotes a considerable amount of attention to foreign leaders and their interactions with their Israeli counterparts. He describes numerous occasions when Europeans, in particular, adopted a patronizing approach, disguising petty political interests with lofty moral rhetoric. In 1973, for instance, Europe’s socialist leaders cowered in the face of the Arab oil embargo and closed their airspace to American planes delivering much-needed weapons during the Yom Kippur War. In response, Golda Meir did not sugarcoat her response to German Chancellor Willie Brandt, who was, in theory, one of Israel’s best friends. As a fellow socialist, she asked, “what possible meaning socialism can have when not a single socialist country in all of Europe was prepared to come to the aid of the only democratic nation in the Middle East?”

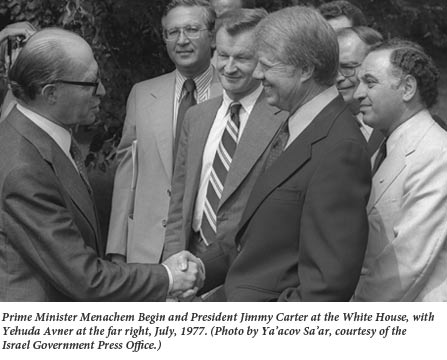

More than half of Avner’s book focuses on Menachem Begin, whom he appropriately identifies as “The Last Patriarch” and “the quintessential Jew.” Avner hadn’t initially expected to work for him, but had assumed that Begin’s accession to high office would mean his own exile from “that marvelously cosseted and privileged environment known as the prime minister’s bureau.” To his astonishment, Begin kept him on, telling him, “with a warm smile, and in English,” that he would “polish my Polish English. You will be my Shakespeare. You will shakespearize it.” This reflects well on Begin, but also on Avner, whose ability to work with such a wide range of leaders, from both Labor and Likud, is a sign of his pragmatic approach to Israeli diplomacy, and constitutes a much needed reminder of the limitations resulting from ideological blinders, both left and right.

Begin, who became prime minister after the 1977 electoral “earthquake,” was even more of a realist than his predecessors, and had no illusions about Europe. In 1981, Begin reprimanded Chancellor Helmut Schmidt for making a statement in Saudi Arabia regarding Germany’s commitment to the Palestinians, which left unmentioned his nation’s obligation to the Jewish people. In response, Begin told Schmidt that his statement “showed callous disregard for the Jews exterminated by his people in World War II.” As Avner recalls, “The pall of the Holocaust clung to Menachem Begin like a shroud, unremittingly.” Later, while serving as the Israeli ambassador in London, Avner was invited to a state banquet in honor of the German president. When the German anthem was played, he imagined Begin’s response, and, diplomatic protocol notwithstanding, stayed in his seat.

In sharp contrast, Begin clung to an idealized image of the United States and its leaders as committed supporters of liberty and freedom. Before meeting President Carter for the first time, Begin told his advisers, “I believe Jimmy Carter to be a decent man, and his impulse is entirely sincere . . . Since I believe him to be an honest man I have to believe he can detect the truth when he sees it, and is, therefore, open to persuasion.”

While maintaining his core beliefs and policies, Begin worked hard to influence Carter, who nevertheless persisted in his efforts to revive the Geneva conference in partnership with the Soviet Union. In November 1977, when Sadat sought to circumvent Carter’s plans by coming to Jerusalem to begin peace negotiations, Begin continued to keep Carter fully informed of developments. Despite many bitter arguments, Begin clung tenaciously to his effort at persuasion, until he recognized that Carter was unalterably committed to an outlook contrary to his own.

The recent events in Egypt have highlighted the importance and unique nature of the 1979 peace treaty with Israel. While much has been written about this remarkable process, Prime Minister Begin’s perspective has been largely unrepresented, in part because he gave few interviews and wrote no memoirs. Avner helps to fill this gap in the literature. In contrast to the image of a rigid leader blindly committed to ideology, his detailed reportage demonstrates the realism that guided Begin’s conduct during his years as prime minister. He understood the importance of peace with Egypt for the future of Israel, reluctantly accepting withdrawal from the Sinai and the accompanying security risks as the price. Avner portrays the prime minister as maintaining a clear view of the objective, and not allowing his emotions to interfere with his judgment. During crises in the difficult negotiations, the Egyptian media used anti-Semitic images for personal attacks against Begin, and referred to him as “Shylock.” But Begin was unruffled, even sending notes to Avner “from Shylock to Shakespeare.”

Begin remained steadfast in the face of pressures from other quarters as well. When the US called for Israel to return to the pre-1967 armistice lines, he declared:

We are a nation of returnees, back to our homeland, Eretz Yisrael. Ours is a generation of destruction and redemption . . . Ours is a generation that rose up from the bottomless pit of hell. We were a helpless people . . . No one came to our rescue. We could do nothing about it. But now we can. Now we can defend ourselves.

But Begin was not immovable. As Avner observes, “Even while the mule in him reared up against any West Bank concessions, the statesman within him strained to rein in his own impulses.” Begin found a formula that “was not an outright avowal of Israeli sovereignty, but nor was it a concession to anybody else’s . . .” After many more rancorous sessions, including two weeks at Camp David in 1978, this remained Begin’s bottom line in the negotiations. He proposed autonomy for the “Arabs of Eretz Yisrael,” as he insisted on calling them, but rejected any move towards an independent state under Arafat’s control. Sadat, as well as Carter, eventually accepted Begin’s bottom line.

Avner’s chapters on Begin and Reagan reflect a different but equally complex relationship, in this case involving a president whose ideological and intuitive sympathy for Israel was often qualified by other American interests. Israel’s attack on Iraq’s nuclear reactor in June 1981, Israel’s annexation of the Golan Heights in December of that year, the massive American sale of advanced weapons to Saudi Arabia, and then the Lebanon war in 1982 created a great deal of stress in US-Israel relations. By focusing on the communication (and often miscommunication) between the leaders of the two countries, Avner adds an important dimension to the analysis of their interaction.

Reagan’s use of “cue cards” during meetings, with no substantive or spontaneous departures from the text, is seen as reflecting the fear of his advisors (including the consistently hostile Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberg), who “did not want their man plunging extemporaneously into exchanges on complex issues…” For Begin, the master orator, this device and Reagan’s inaccessibility were as frustrating as Carter’s refusal to respond to his passionate lectures on Jewish history and rights.

The final chapters of Avner’s book respectfully portray Begin’s decline in the wake of accumulated political and physical stress, accelerated by the death of his wife, Aliza. As in the case of the other prime ministers featured in this diplomatic history, the personal is secondary to the political realm, but never entirely removed from it. The image of a very weak and largely dysfunctional Begin attempting to deal with the Lebanon war, which went terribly wrong, highlights the centrality of leadership, in both its positive and negative aspects.

Begin’s official resignation in August 1983 marked the end of the era that began with Ben-Gurion, in which Israel was led by the charismatic heads of the pre-state Zionist movements. In their own different ways, they all worked indefatigably to translate their absolute belief in the centrality of Jewish sovereign equality into the form of a state capable of surviving and prospering in “a difficult environment.” And in realizing this objective, they gave their successors the opportunity to maintain and build on their achievements. Yehuda Avner, who saw so much of this up close, who was “present at the creation,” deserves our thanks for supplying us with such a vivid and instructive reminder of the very special men in whose service he utilized his own unique talents.

Suggested Reading

Conversion, “Catholic Israel,” and the Jewish Future: An Exchange

Tal Keinan argued for a radical transformation of Jewish life in God Is in the Crowd. Our editor wasn't convinced, which led to a pointed but cordial discussion.

My Father and Birnbaum’s Heavenly City

According to one scholar, Uriel Birnbaum produced “more than 6,000 poems, 130 essays, 30 plays, 10 short stories, 15 fairy tales, fragments of a longer epic poem, 20 chapters of a lost novel and 30 collections of illustrations.” And yet, Birnbaum received little acclaim in his lifetime. Today he is all but unknown.

Leapsniffing through the Vimveil: Avram Davidson’s Fantastic Fiction

Gods in fishbowls, men who are apes, and a Jewish dentist abducted by aliens: the fantastic fiction of Avram Davidson was almost as strange as his life.

As the Story Goes: Hanukkah Spears, Cheese, and Goblins

Where did all the Hanukkah stories go?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In