Total Eclipse of the Brakha

On April 8th, the Great North American Eclipse will occur, drawing the curious to its northeastern pathway. We’ll stand in parking lots and parks, sit on car hoods and beach chairs, and, if we’ve planned ahead, wear eclipse glasses from a reputable vendor. No matter how much we prepare ourselves I expect that we’ll gasp, just a bit, when the skies darken, the temperature drops, and the disk of the moon obscures the sun. Eclipses are well understood natural phenomena, but that doesn’t take away their wonder. Experiencing that wonder, Jews that gather may reach for a brakha, a blessing, to say. Except that there isn’t one. Although there are several that can be put to work, there is no agreed upon blessing because eclipses are not just natural wonders, but, according to the Talmud, bad omens. And Jews don’t bless bad omens.

There is a deep tension in Judaism over how to understand eclipses. Are they simply materialist, astronomical, orbital phenomena, or are they a spiritual, astrological, divinatory force? The darkness of an eclipse must have been terrifying to witness in ancient times before they could be predicted. After all, to punish the Egyptians, Moses was told to “stretch out [his] hand toward heaven and there will be darkness over the land of Egypt; and the darkness will eclipse all things” (Ex. 10:21). The Talmud says an eclipse is a result of sin, and the omen can fall on everyone:

When the [heavenly] lights are eclipsed, it is a bad omen for the enemies of the Jewish people, [which is a euphemism for the Jewish people,] because they are experienced in their beatings. . . . When the sun is eclipsed, it is a bad omen for the other nations. When the moon is eclipsed, it is a bad omen for the enemies of the Jewish people. . . . When the sun is eclipsed in the east, it is a bad omen for the residents of the east. When it is eclipsed in the west, it is a bad omen for the residents of the west. When it is eclipsed in the middle of the sky, it is a bad omen for the entire world. (Sukkah 29a)

The Talmud further drives home how to interpret these omens:

If, during an eclipse, the visage [of the sun] is like blood red, [it is an omen that] sword is coming to the world. [If the sun] is black like sackcloth [it is an omen that] arrows of hunger are coming to the world. [When it is similar both] to blood, and to sackcloth, it is a sign that both sword and arrows of hunger are coming to the world.

While predicting the specific locations of a solar eclipse wasn’t to happen until the 1700s, the eighteen-year solar eclipse cycle was known to the Babylonians and Assyrians by the eighth century BCE. This, of course, raises questions about the Talmud’s descriptions. How could solar eclipses be both materialist, occurring as part of a natural cycle, and spiritual, appearing as needed to indicate future punishment for past misbehavior?

Rabbi Judah Loew, the Maharal of Prague, attempted to answer the question. According to him, eclipses are a bad omen that occur because of sin, but if we lived in a sin-free world, God would have created the universe without solar eclipses. Instead, God would have kept the moon and the sun from ever occluding each other. No sin would mean no need for bad omens and therefore no eclipses. This model, as noted by Jeremy Brown, would, among other problems, create the unfortunate cosmic problem of making the moon always completely visible, and eliminating the practice of Rosh Chodesh. So maybe God knew what He was doing.

More recently than the Maharal, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, presented another solution. Like the Maharal, the Rebbe started with a statement of faith in the sages of the Talmud, stating that eclipses are, without question, bad omens. But the Rebbe, who had studied mathematics and physics in Paris and Berlin, tried to wrestle with how they could also be required by the laws of nature. Where the Maharal’s explanation was mechanistic, contemplating different orbits in a sin-free universe, the Rebbe’s was spiritual. He observed that the point of the bad omen was so that we would see it, repent, and return to God. Therefore, the only ones who would be affected by the bad omen would be those who had strayed from God and therefore benefit from the reprimand. To the Rebbe, the solar eclipse itself is not the consequence of our behavior. It is simply a vehicle for the delivery of the warning.

This leads us back to the debate over the blessing. There is an extremely wide range of Jewish blessings for a wide range of experience—we bless new births, the food we eat, the clothes we wear. We bless storms, earthquakes, and rainbows. But we have no set blessing for an eclipse. In his 2017 essay “There Is No Bracha on an Eclipse,” Rabbi Michael Broyde notes the lack of support for a blessing over a solar eclipse in the Shulchan Arukh and other sources, despite the provision of blessings for other natural phenomena including “stalagmite caves, waterfalls, water geysers, volcanoes and many more.” While some suggest that the Shulchan Arukh’s list is not meant to be exhaustive and can be expanded when new wonders are found, Broyde points out that solar eclipses are not new. And since “some thought that eclipses were punishments . . . no blessing was ordained.” So, both for material reasons (eclipses are a well-known wonder that never had a blessing), and for a spiritual reason, (eclipses are a bad omen), we shouldn’t make a brakha.

Meanwhile, in his essay “Solar Eclipse: To Bless or Not to Bless,” Rabbi Dov Linzer, Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, acknowledges many of the issues that Rabbi Broyde brings up, but expands the argument. He writes:

What does it mean when our religious impulse to praise God and see God in the world is not able to find expression in halakhic forms, such as the recitation of brakhot? Does this not run the risk of making halakhah an experience only of following rules…and not a vehicle to express and experience ahavat Hashem [the love of God]?

He concludes by arguing one should express awe and amazement at an eclipse by making the brakha of Oseh Maaseh Bereshit—the blessing on the creation of the world: Baruch Atta Adonay Elokeinu Melekh Ha-Olam Oseh Maaseh Bereshit—Blessed are you Lord our God, Ruler of the universe who makes the world of Creation. In doing this, Rabbi Linzer spins the spiritual aspects of the solar eclipse in a new direction. It is a new opportunity for reverence and wonder.

For those of us who gather with beach chairs and glasses, the darkening sky and glittering solar corona will take familiar locales and make them strange, providing us each with the opportunity for a moment of awe. This moment has been shared and its implication over argued for millennia; an omen and opportunity to return to God, a chance to stand before God in wonder, or a chance to appreciate the spectacular consequences of the orbital cycles of moon and sun. It’s a chance to say a blessing, or a private prayer, or nothing at all, and experience, as Moses and the Hebrews and the Egyptians did, the moving darkness.

Suggested Reading

Letters, Spring 2021

Of Ballads and Baloney, The Singer or the Song?, The American Question, Against Artichokes, and More

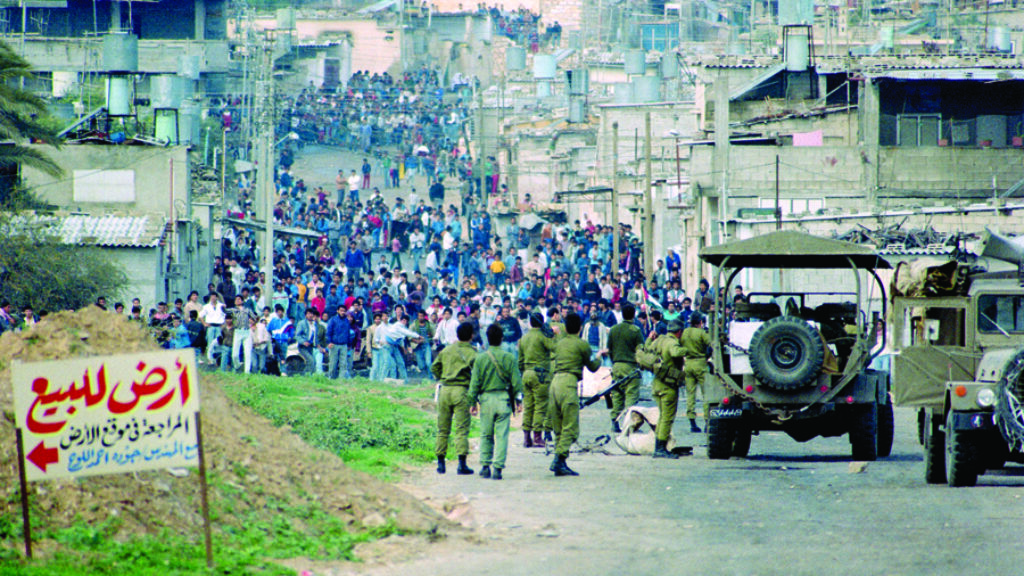

The Ethics of Protective Edge

How does one deal with Hamas, an enemy that has eliminated any trace of the distinction between combatants and non-combatants, except for the purposes of propaganda?

Hollywood’s Anti-Nazi Spies

In 1934, Hollywood's Jewish moguls met secretly at the Hillcrest Country Club to hear an unusual pitch: find Nazis in America, and stop them.

Translating and Remembering Chaim Grade

A memoir of faith, literature, and chickens.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In