Not So Innocent Abroad

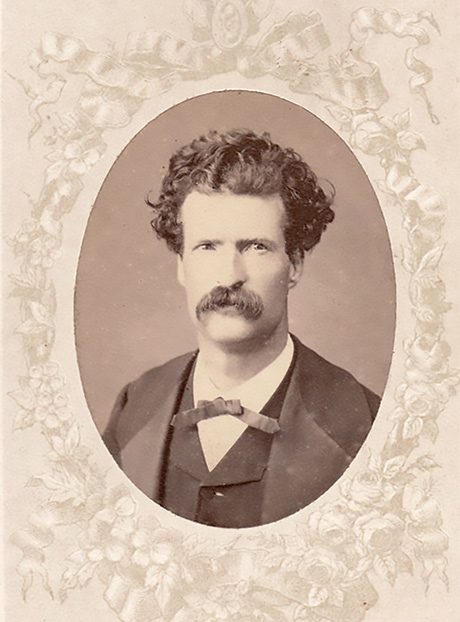

If the 32-year-old Mark Twain had not visited Jerusalem in 1867, near the very start of his career, would he still have become the American Sholem Aleichem?

That was the admittedly odd question going through my mind as I viewed the remarkable exhibit Mark Twain and the Holy Land, on display at the New-York Historical Society until February 2, 2020. It celebrates the 150th anniversary of the 1869 publication of Twain’s second book, The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrim’s Progress, the author’s wry-eyed travelogue of the five-and-a-half-month luxury steamship cruise that would carry him and his fellow shipmates across the Atlantic Ocean, through the Mediterranean Sea, and on to its ultimate destination, the Holy Land.

Although relatively few readers today would rank this volume as their favorite among Twain’s works—that honor would more likely go to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Life on the Mississippi, or The Adventures of Tom Sawyer—it was, in fact, his bestselling book over the course of his lifetime and remains one of the bestselling travel books of all time. In achieving literary fame so early in his career—his only previous book was The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, and Other Sketches—Twain jumped onto his own trajectory of authorial celebrity, his name (or pen name, his birth name being Samuel Langhorne Clemens) recognized throughout the world. So well-known was he that, legend has it, upon meeting Sholem Aleichem in New York in 1906, the great Yiddish writer and humorist was introduced to him as “the Yiddish Mark Twain.” In response, Twain is said to have graciously quipped that, no, it was he who was “the American Sholem Aleichem.”

While neither Sholem Aleichem nor his most famous character, Tevye the Dairyman, made it to the Holy Land, Mark Twain did. The American literary critic Leslie Fiedler may have had Twain’s collegial quip in mind when, in the afterword to the tattered paperback copy of The Innocents Abroad I took down from my bookshelf, he described the comic voice Mark Twain used here as that of a “schlemiel . . . a wandering jester.”

It is this Twain, the roving author in all his sardonic splendor, who is on display in both the exhibit (organized in partnership with the Shapell Manuscript Foundation) and the book itself. Twain stepped aboard the steamship Quaker City on June 8, 1867, his fare of $1,250 (comparable to around $20,700 today) paid for by the San Francisco newspaper Alta California in return for twice-weekly dispatches about the trip for the paper; it was these columns that he subsequently reworked into the book published in 1869.

The exhibit is relatively small, filling a single gallery. But, the array of 19th-century photographs depicting the sites of Jerusalem and its surrounding environs, the numerous original manuscripts and letters in Twain’s own hand, and the various period maps, postcards, prints, travel posters, and souvenirs brought home (most notably a pair of velvet slippers embroidered with golden thread) take you through the journey as surely as Mark Twain does in his distinctive narrative voice.

An atmospheric oil painting depicts the Quaker City steamship itself, with its prominent broad sidewheel and two tall steam pipes emitting wisps of black smoke, as it sits in calm blue waters with misty mountains in the background. As for the Quaker City’s journey, a large map spread across one wall allows you to trace the itinerary of the 163-day trip halfway around the world and back via steamship, train, caravan, and horseback. It details stops in the Azores, Tangiers, Spain, France, Italy, and Greece. Then Twain was on to the Black Sea ports of Constantinople, Odessa, and Sevastopol. There were debarkations at Smyrna, Beirut, Damascus, Jaffa, Jerusalem, and finally Egypt, before heading back across the Atlantic Ocean to Bermuda, and then New York, where the intrepid travelers arrived safely on November 19.

Twain sent characteristically cantankerous descriptions home from all these stops. The vaunted beauties of Italy’s Lake Como are nothing, he contends, compared to the transparent waters of Lake Tahoe, where, he says, “one can count the scales on a trout at a depth of one hundred eighty feet.” He grows weary of the endless parade of religious-themed paintings he encounters throughout Europe: “[T]o me it seemed that when I had seen one of these martyrs I had seen them all. They all have a family resemblance to each other.” In Constantinople, he finds that “[m]osques are plenty, churches are plenty, graveyards are plenty, but morals . . . are scarce. . . . They say the Sultan has eight hundred wives. This almost amounts to bigamy. It makes our cheeks burn with shame to see such a thing permitted here in Turkey. We do not mind it so much in Salt Lake City, however.”

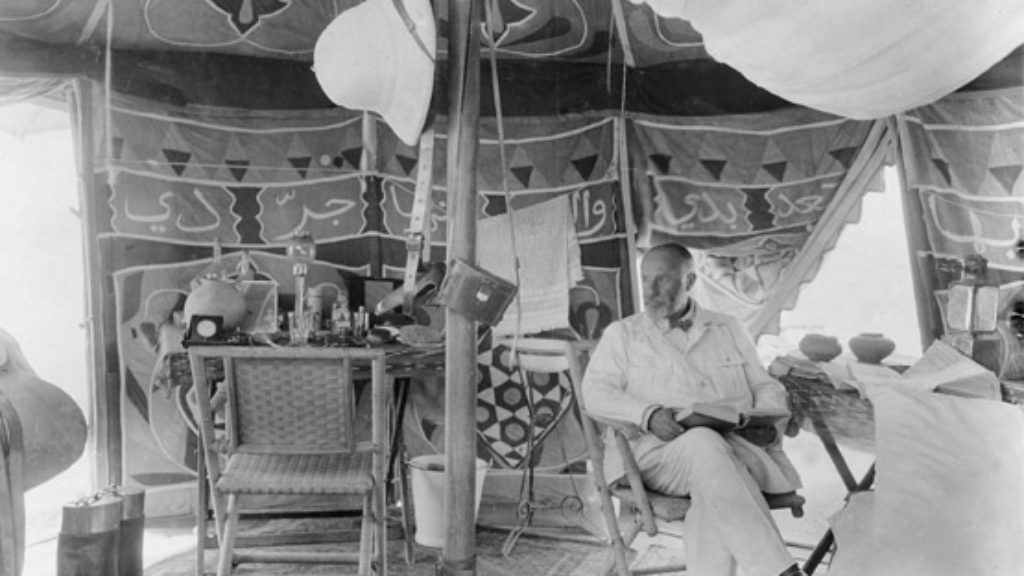

But the voyage’s main attraction was the Holy Land. Pleasure trips to Palestine, which was then a province of Syria and under Ottoman rule, were still novel, with the Quaker City excursion at the cusp of an emerging travel trend. Many of Twain’s 70-some fellow passengers on the trip were pious, sober-minded Protestants who frowned on Twain’s gambling, drinking, smoking, and cursing. Twain poked fun at these “pilgrims” and their unquestioning parroting of the romanticized chronicles of Holy Land travels that he, like them, had perused in preparation for the trip. The travelers’ guidebook of choice was William C. Prime’s Tent Life in the Holy Land—an 1857 copy of which is displayed in the exhibit, open to a page showing an illustration of the domed structure of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Twain’s account of Prime’s purported adventures is characteristically droll:

He went through this peaceful land with one hand forever on his revolver, and the other on his pocket-handkerchief. Always, when he was not on the point of crying over a holy place, he was on the brink of killing an Arab. More surprising things happened to him in Palestine than ever happened to any traveler here or elsewhere.

Throughout the trip, Twain highlighted the disparity between the desire of his guidebook-led companions to see what they had been promised and the reality of what was actually in front of them. The contrast reached its peak once they arrived in the Holy Land. “I must studiously and faithfully unlearn a great many things I have somehow absorbed concerning Palestine,” he commented, beginning with the reality of the relatively small size of the local grapes he saw, as opposed to the enormous vines portrayed in his favorite Bible story illustrations:

I must begin a system of reduction. Like my grapes which the spies bore out of the Promised Land, I have got everything in Palestine on too large a scale. . . . The word Palestine always brought to my mind a vague suggestion of a country as large as the United States. . . . I suppose it was because I could not conceive of a small country having so large a history.

Similarly, Jerusalem itself seemed “[s]o small! Why, it was no larger than an American village of four thousand inhabitants,” he wrote.

What seemed to rankle most—and brought out some of Twain’s most biting satire—was the fanciful commentary provided by local guides eager to show the travelers sites such as “the tomb of Adam.” He writes, “How touching it was, here in a land of strangers, far away from home and friends and all who cared for me, thus to discover the grave of a blood relation. True, a distant one, but still a relation.”

Religious skeptic though Twain was, he was well schooled in the Bible. His mother, to whom he remained devoted throughout his life, had seen to that. Indeed, one of the most striking items on display is the present he brought back for her from Jerusalem: a King James Bible handsomely bound in oak, olive wood, and balsam wood. The cover, front and back, is engraved with the word “Jerusalem” in Hebrew, with the inscription, “Mrs. Jane Clemens—from her son—Mount Calvary, Sept 24, 1867.”

It was Twain’s drollery, balanced between his skeptical respect for the Bible and his irreverent view of humanity, that led to the success of The Innocents Abroad, suggested Jonathan Sarna, professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University, at a program related to the exhibit at the New-York Historical Society. But beyond Twain’s 1867 voyage, Sarna commented, it was his travels to Europe in the 1890s that brought to the fore his rejection of anti-semitism. In Paris, he was shocked by the visceral antisemitism exhibited in the Dreyfus affair. Visiting Vienna, he was condemned by the increasingly antisemitic press there for meeting with leading Jewish intellectuals such as Sigmund Freud and Theodor Herzl.

Back home, Twain published his well-known 1898 Harper’s essay, “Concerning the Jews.” There he writes: “A few years ago a Jew observed to me that there was no uncourteous reference to his people in my books, and asked how it happened. It happened because the disposition was lacking. I am quite sure that (bar one) I have no race prejudices, and I think I have no color prejudices nor caste prejudices nor creed prejudices. Indeed, I know it.” More proof of that assertion arrived a decade later, when he wholeheartedly accepted his daughter Clara’s marriage to the Russian Jewish pianist and conductor Ossip Gabrilowitsch. But why be surprised? He was, after all, the American Sholem Aleichem, and the Yiddish Mark Twain would not have expected anything else.

Suggested Reading

Walkers in the City

Herman Melville was unimpressed with Jerusalem in 1857, but what would he say if he were a saunterer on Mamilla or King George today?

Islamic Jihad, Zionism, and Espionage in the Great War

A century ago, the Holy Land seems to have been full of European adventurers, archaeologists, would-be diplomats, and spies—sometimes all combined in the same person. Take, for instance, Max von Oppenheim . . .

The Lowells and the Jews

Robert Lowell, the most famous poet in America, icon of the antiwar movement, consummate Boston Brahmin, was especially glad to speak with a Jewish group because, he drawled, “I’m an eighth, you know.”

The Homecoming

A 1977 Jerusalem Post article on Harold Pinter's visit to Israel was enticing but short on details. Pinter had just been to the Dead Sea (“hot!”) and Mount Masada (“high!”) and was planning to visit a cousin who lived on a kibbutz.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In