Brother Baruch

There has never been and probably will never again be a more famous excommunication in Jewish history than the one inflicted upon Baruch Spinoza in Amsterdam in 1656. Less well known, but familiar to most students of modern Jewish history, is the symbolic effort to rescind that ban undertaken by Hebrew University Professor Joseph Klausner. In February 1927, at the newly established university’s commemoration of the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Spinoza’s death, Klausner delivered a lecture in which he objectively sized up the heretical philosopher’s achievements. Then he jolted his audience with his unforgettable peroration:

To Spinoza the Jew, it is declared . . . The ban is nullified! The sin of Judaism against you is removed and your offense against her atoned for! Our brother are you, our brother are you, our brother are you!

Some people left the auditorium (Gershom Scholem tells us) mocking Klausner’s theatricality and his improper recourse to the phrase traditionally used to end a rabbinic ban. In the long run, however, Klausner’s words have become a frequently noted sign of the revolutionary turn in Zionist thinking that transformed quite a few former outcasts into heroes. That Daniel B. Schwartz would focus on it in his discussion of “Spinoza’s meaning for Jewish modernity” was inevitable. But his exceedingly careful study shows that Klausner’s position on this matter was not as simple as many have thought, and by no means as unequivocal as that of, say, Spinoza’s greatest Zionist champion, David Ben-Gurion.

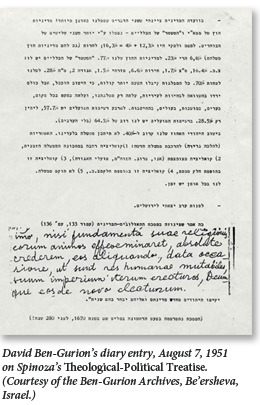

“The ‘Old Man’ of the Yishuv and Israeli politics,” Schwartz reminds us, “was an ardent admirer of the Amsterdam philosopher.” Ben-Gurion applauded his combination of a scientific spirit with a spirituality that had its roots in the Bible, his laying of the foundations for, as Schwartz puts it, “the prime minister’s dream of transforming the Hebrew Bible from a work of transcendent revelation into a national epic,” and, perhaps above all, his anticipation of Zionism. Like many Zionists before him, Ben-Gurion seized upon the passage in the Theological-Political Treatise where Spinoza speculates that the Jews might one day restore their independence, if only they were to abandon the principles of their religion that “effeminate their hearts,” and read it, very implausibly, as a call to arms if not a prophecy.

Once he was prime minister, Ben-Gurion wanted to go far beyond a shout-out to Spinoza. He hoped to honor the man he called “the most original thinker and the most profound philosopher that Jewry has produced in the past two thousand years” with “the publication of a complete and critical edition of Baruch Spinoza’s writings by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem” in time for the three hundredth anniversary of his excommunication in 1956. Schwartz discusses this effort in some detail but, on the whole, devotes a lot more attention to the relatively obscure Klausner’s attitude toward Spinoza than he does to that of the man who was arguably the most famous Jew of the 20th century. And he does so with good reason.

In his chapter dealing with the “Zionist rehabilitation of Spinoza,” Schwartz makes no attempt to be comprehensive. Although he acknowledges, in his footnotes, that the “Zionist reception of Spinoza remains mostly understudied,” he tells us in his text only a fraction of what he obviously knows about it. He makes Klausner and not Ben-Gurion one of the pivotal figures in his narrative not because he considers him to be more important but because of what he represents. Fundamentally, he informs us, Jewish nationalism’s appropriation of Spinoza added up to “a debate over the meaning of Zionist secularism,” and in this debate, Klausner, over the years, occupied more than one position.

In 1927, in Jerusalem, Klausner argued that even though “Spinozism is not Judaism in the purest sense of the term,” it was still, despite its atheism and its utter irreconcilability with the teachings of the prophets, “part of an uninterrupted chain” extending “to our generation and until the end of all generations.” Klausner then regarded Spinoza’s system, as Schwartz puts it, as “a product of the Jewish national impulse.” Back in 1911, however, in a dispute prompted by the attempt of Y. H. Brenner and some other young Hebrew writers to push the envelope of Jewish culture open too widely, Klausner had insisted, like his mentor Ahad Ha’am, “that secular Jewish culture had to maintain an organic link to its religious past and avoid the temptation of what he called “de-historicization.” It could not leave the prophets behind.

As Schwartz shows, it was with very similar arguments that some secular Zionists objected, much later, to what Klausner tried to do in 1927 and what Ben-Gurion attempted at a later date. He mentions, for example, a man named Yehoshua Manoah, one of the founders of Deganyah, the first kibbutz, who from 1954 to 1956 “engaged in a dialogue in the Hebrew press” with the rather busy prime minister (believe it or not!) “over the propriety of celebrating Spinoza from a national Jewish perspective.” As Manoah wrote,

“I am not religiously observant, but for me (and I don’t care what others think) anybody who belittles the stature of Moses, our teacher (Moshe rabenu), speaks ill of the Prophets of Israel, shows disrespect to the Hebrew Bible, our book of books, which in my eyes has no equal—I want nothing to do with his philosophy.

In the sentences that follow his discussion of Manoah, Schwartz underscores his significance and at the same time clarifies the strategy underlying his own treatment of the Zionist reception of Spinoza:

One of the great secular champions of the reappropriation of the Amsterdam philosopher for Hebrew culture shared with one of its vehement secular critics a nearly verbatim concern over unchecked secularization. By going beyond attention-grabbing gestures like Klausner’s lifting of the cherem [excommunication], and appreciating the anxiety over where to draw the line between “freedom” and “heresy” they obscure, we gain more complex insight not only into the Zionist use of Spinoza, but into an essential tension within the Zionist formation of the secular.”

Not the actual Spinoza of history but what Schwartz calls “the Spinoza of memory” is the subject of this book, which examines this being’s manifestations not only in the Zionist world but in “constructions of nontraditional Jewishness—assimilationist, cosmopolitan, and national—from the 19th century to the present.” What Schwartz has produced is not, however, the catalogue that this sentence from the book’s epilogue might lead one to expect. Throughout his narrative, Schwartz takes people out of the pigeonholes into which previous scholars have tended to place them.

Take Berthold Auerbach, for instance, the popular 19th-century German novelist who started out in life as a yeshiva boy and came close to becoming a Reform rabbi before he earned his fame as the author of stories about Black Forest village life. His 1837 Spinoza: A Historical Novel was, as Schwartz notes, not only “the first attempt ever made to portray Spinoza as a fictional protagonist” and an influential work in Germany in general but “a landmark in his Jewish reception.” Auerbach wrote it only a year after he published a long pamphlet entitled Judaism and Recent Literature, in which he described Judaism, in Schwartz’s words, “as a religion whose nature and history vouched for its capacity for progress.” Some previous scholars have read Auerbach’s Spinoza in the light of this pamphlet; more have perceived the book “as a plea for Enlightenment universalism against all forms of religious particularism.” Schwartz, for his part, makes a strong argument that the narrative is ambiguous and leaves us wondering.

Is the enlightened and emancipated society imagined here as Spinoza’s legacy compatible with an ongoing and positively affirmed Jewish difference—with the view expressed in Das Judentum that “Judaism can and will satisfy every need of mankind for all time”? Or is Spinoza being invoked as the forerunner of a fully assimilationist vision of the future that will climax in the dissolution of all confessional identities in a universal community of humanity?

Schwartz is no less attentive to the 20th-century reception of Spinoza in Yiddish than he is to the earlier one in German. “To this day,” he says, Jacob Shatzky’s Spinoza un zayn svivoh [Spinoza and His Environment], published in 1927, “remains the most significant exemplar of a Yiddish scholarly account of the life and times of the Amsterdam philosopher.” (I haven’t read the book myself, but I’m willing to take Schwartz’s word for this and go out on a limb and predict that it will remain forever the most important such book in Yiddish.) But the figure in what he deems “the Yiddish Spinoza renaissance” to whom he devotes the most attention is Isaac Bashevis Singer. Schwartz astutely analyzes his famous story “The Spinoza of Market Street” as well as other much less familiar depictions not of Spinoza but of rather unworldly and pathetic Jewish Spinozists in his fiction. He arrives at the conclusion that “Singer clearly judged the modern Jewish attachment to Spinoza to be a path wrongly taken, a source not of comedy, but of tragedy.”

At the very end of his book’s last chapter, Schwartz observes that for Singer, unlike the other figures discussed earlier in the volume, Spinoza was neither a liberator from the ghetto nor a prototype of Zionism. But that doesn’t mark the end of Schwartz’s story. In a brief epilogue, he takes note of the most recent manifestations of the ongoing process of re-envisioning Spinoza, from Yirmiyahu Yovel’s two-volume Spinoza and Other Heretics, a top bestseller in Israel in the late 1980s, to Steven Smith’s Spinoza, Liberalism, and the Question of Jewish Identity from the following decade, to Rebecca Goldstein’s idiosyncratic Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity in 2006. One of the things that emerges with clarity from these final pages is that the nationalist concern with Spinoza is simply gone. Yovel says that Spinoza may have been a “closet Zionist,” and Smith thinks he may perhaps have been “the founder” of political Zionism, but neither of these scholars nor anyone else, it seems, has felt the need to reaffirm the connection that meant so much to David Ben-Gurion. Another thing that stands out is the similarity between the positive depiction of Spinoza on the part of Berthold Auerbach and others and some of the most recent appropriations of Spinoza as a secular hero.

But there is also something new on the horizon. While Spinoza used to be, for so many thinkers, a guide and a model for rebellion and exit from Jewish tradition, Schwartz sees some signs that he might now be performing an opposite function. Could it be, he asks, that for contemporary secular Jews whose starting point is complete estrangement from Judaism “the turn to the prototype of the secular Jewish intellectual allegedly ‘lost’ to Jewish culture might also be understood as a return to identity?” It is hard to imagine anything that would have come as more of a surprise to Spinoza or, for that matter, the people who excommunicated him.

Suggested Reading

Light and Darkness

A great novelist and close reader of Calvin, , Marilynne Robinson has now written a luminous commentary on Genesis.. But is her God more predictable than the God of Abraham?

The Story They’ve Been Telling Themselves

“I wouldn’t turn on my beloved, my sacred husband,” Eva Panić firmly declared. Instead, she chose a brutal Yugoslavian prison–and abandoned her six-year-old daughter. David Grossman transforms their story into a disturbing yet beautiful novel.

The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

After he visited the odd talmudic genius, Bialik said that “two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.”

Saving the World

There are at least two problems with the widely repeated narrative about Rosenzweig's sudden commitment to Judaism: It’s historically false and philosophically pernicious.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In