A Serious Comedy

Fitzgerald believed The Great Gatsby was about American WASPs, but it’s really about a Jewish gangster trying to pass. Hemingway believed A Farewell to Arms was about a man’s disgust with war, but it’s really about the sky in Italy, the way the snow creaks beneath your boots in storm-struck alpine towns, the residue that settles at the bottom of a good bottle of wine. An artist does not know the meaning of his own work. If he thinks he knows, he’s wrong. If he had a plan and believed that he’d carried it out, he’s probably failed. If, on the other hand, he had a plan and knows he failed, there’s a chance that he’s succeeded. He aims for one thing and hits another.

Take the films of Joel and Ethan, the Coen Brothers. Starting with their first movie, Blood Simple, their movies might have seemed to be about nothing less or nothing more than the art of filmmaking itself. Each picture has been an occasion to experiment with a classic Hollywood genre. Western. Gangster flick. Newspaper comedy. But their real project, even if they’re not aware of it, has been more particular. It’s about a sensibility, a way of seeing the world common to a species of pop culture–drunk American Jews, with an emphasis on a unique genus: midwestern Hebrew. In other words, though the Coens have explored characters as goyish as Anton Chigurh (No Country for Old Men) and Rooster Cogburn (True Grit), their work is as Jewish as Saul Bellow (or Bob Zimmerman).

This has mostly been sublimated, hidden. (As the old Hollywood axiom has it, “Write Yiddish, cast British.”) When not hidden, their Judaism is played for laughs. As in The Big Lebowski, when convert Walter Sobchak, told he’s been living in the past, says, “Three thousand years of beautiful tradition from Moses to Sandy Koufax? You’re goddamn right I’m living in the fucking past!” Or in Hail, Caesar! when a rabbi, asked to comment on the plot of a biblical epic, says, “God has children? What, and a dog? A collie, maybe? God doesn’t have children. He’s a bachelor. And very angry.”

But now and then you see the thing plain. Take A Serious Man, which was near the top of my quarantine rewatch list. It’s this movie that shows the brothers for what they truly are: the exemplary American Jewish pop artists of the century, seeking to portray neither the experience nor the trials of the Jews but instead a certain Jewish sensibility, the world as it looks through the eyes of the modern midwestern Hebrew.

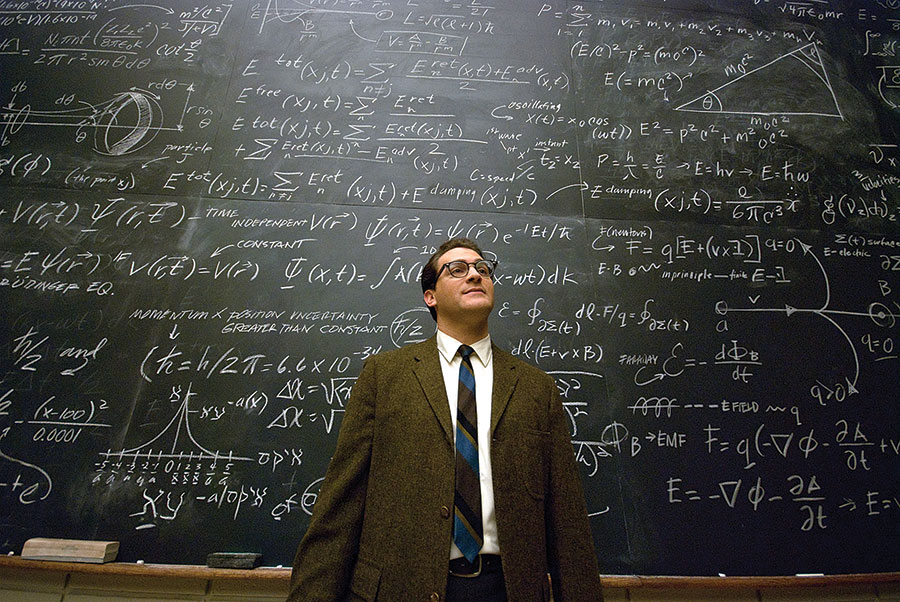

A Serious Man, 2009. (Wilson Webb/©Focus Features/Courtesy Everett Collection.)

Such Jews—the Coens grew up in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis—came of age in a kind of triple exile: first from Zion, then Europe, and now New York, the center of American Jewish life, capital of Jewish delis, Jewish streets, Jewish basketball and stoopball, synagogues, density, and sophistication. In places like St. Louis Park, young Jews were routinely told that whatever they were doing was being done better by Jews somewhere else. You like that corned beef? Well, they make it better in New York. You like that musical? Well, the real Tevye is on Broadway.

Joel was born in 1954, Ethan three years later. Three years is long enough for separation but short enough to share the same mind, the same books, TV shows, and dreams. Having gotten hold of a Super 8 camera in the early 1970s, the brothers began making their own movies. They started with knockoffs of those they’d seen on TV. In the way of student painters, they learned by tracing the works of the masters: Preston Sturges, Frank Capra.

They preferred to be behind the camera from the start and left most of the early acting to a neighborhood kid named Mark “Zeimers” Zimering, their first leading man. It was Zeimers who blazed the way for George Clooney, Frances McDormand, John Goodman, and the rest of their regular rotating crew. In the Coens’ preteen remake, Cornel Wilde’s The Naked Prey became Zeimers in Zambezi. Lassie Come Home became Ed . . . a Dog. Other Coen juvenilia includes Lumberjacks of the North, The Banana Film, and Henry Kissinger, Man on the Go.

Joel went to NYU, where he did what you’d expect him to do—studied cinema. Ethan went to Princeton, majored in philosophy, and wrote a thesis on Ludwig Wittgenstein. The brothers got hold of a professional camera after college, used it to film a trailer for the movie they wanted to make, and then used the trailer to raise the money to make it. That film, Blood Simple, which starred John Getz and McDormand, is a murder-for-hire crime story. They took the title from Dashiell Hammett’s brutal novel Red Harvest. “It’s an expression he used to describe what happens to somebody psychologically once they’ve committed murder,” Joel told Time Out. “They go ‘blood simple’ in the slang sense of ‘simple,’ meaning crazy.” The movie plays like a tribute to Bogart’s Hollywood.

A great run of movies followed—17 features in 25 years, a Philip Roth–like level of productive regularity. Their second film, Raising Arizona, established their style, which is about wit, words, and antic humor. And speed. Their love of parody seemed to characterize the generation that came after the boomers—every story has been told, every song sung. For the Coens, and the rest of us, there were no new ideas. Style was philosophy, riffing on the masters. These movies speak to those of us who spent our first days drenched in TV and, as a bonus, seem to irritate those who came before, who, in the way of adults, stand at the edge of the playground, calling on them to act their age. Here’s Daphne Merkin writing in the New Yorker in 1998:

Still, all the brothers’ intelligence and skill can’t make up for the sense of vacancy in their movies. Until they find a way to let a little real life in (grownup reality, that is), Joel and Ethan Coen will somehow seem stunted—no more than the brightest kids in the class.

Amazingly, though, they found a way to address the realest of subjects—their own childhood, their own sense of Judaism—without sacrificing their style; they “grew up” without losing their humor. I’m thinking of A Serious Man, which is pitched as a modern-day book of Job—the good man being punished for a crime he did not commit—but is really about the living rooms, yards, and treeless suburban streets where the Coens learned about the world.

The movie takes place in the 1960s in a suburb much like St. Louis Park, where identical ranch houses line the broad streets. If you wandered into the wrong house, you wouldn’t even know it till dinnertime. The movie’s protagonist, Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), is a college professor, as was the Coens’ father. When the action starts, he’s going over the Heisenberg uncertainty principle with his physics class—a theory that had already been explained in the Coens’ 2001 feature The Man Who Wasn’t There:

They got this guy, in Germany. Fritz something-or-other. Or is it? Maybe it’s Werner. Anyway, he’s got this theory, you want to test something, you know, scientifically—how the planets go ’round the sun, what sunspots are made of, why the water comes out of the tap—well, you gotta look at it. But sometimes you look at it, your looking changes it. You can’t know the reality of what happened, or what would’ve happened if you hadn’t-a stuck in your own goddamn schnoz. . . . Sure, it sounds screwy, but even Einstein says the guy’s on to something.

A Serious Man takes place in the weeks leading up to the bar mitzvah of Larry’s son, Danny. In just a few days, Larry, who is awaiting the decision of his school’s tenure committee, is faced with an unfaithful wife, her jackass paramour, a student trying to bribe his way into a passing grade, and an antisemitic buck-hunting neighbor.

In a search that comes to resemble a fable, Larry seeks answers (Why is this happening to me?) from three rabbis—young, middle-aged, old—each of whom represents another generation of failing American Jewry. First the junior rabbi, Rabbi Scott (Simon Helberg). Larry is troubled by his lack of experience, but Rabbi Scott, who comes off as a fool, offers what may be the movie’s only useful advice:

I, too, have had the feeling of losing track of Hashem, which is the problem here. I, too, have forgotten how to see Him in the world. And when that happens, you think, Well, if I can’t see Him, He isn’t there anymore; He’s gone. But that’s not the case. You just need to remember how to see Him.

Then the second rabbi, Rabbi Nachtner (George Wyner), who’s like every rabbi in my Reform synagogue, the spiritual macher of all those Rodeph Shaloms and Beth Israels—behind the big desk, sipping from an ornate teacup, speaking in a pseudo-talmudic singsong in which the most mundane phrase is presented as wisdom. Rabbi Nachtner answers Larry’s big question (Why is this happening to me?) by telling a story. It’s about a “goy’s teeth.” One day, a fellow congregant, an orthodontist making a plaster mold, discovered Hebrew letters carved into the back of a patient’s incisors. They spelled the phrase, Help Me, Save Me. Believing these words to be a message meant for him—the patient’s mouth being a kind of envelope—the orthodontist set off on a quest similar to Larry’s. But in the end, after fruitlessly searching for answers, he simply gave up, returning to a happy, riddle-free life. Which, according to Nachtner, is the point: “These questions that are bothering you, Larry, maybe they’re like a toothache. We feel them for a while; then they go away.”

Then the third rabbi, an old man, a bearded grandfather who reeks of old books and Europe, the inscrutable Senior Rabbi Marshak (Alan Mandell), whose cavernous office is guarded by a pitiless secretary. She sits before his door like a sentry. At this point in his life, Marshak meets only with bar mitzvah boys, speaks only to children. When Larry pleads for an audience, the secretary says the rabbi is busy.

“He didn’t look busy,” Larry shouts.

“He’s thinking,” says the secretary.

The message, for those of us who grew up in the shadow of such rabbis, is clear: the tradition is exhausted; the old men have nothing to teach. Whatever we need can be found on the television or radio. In fact, some of the only words spoken by Marshak come from a song he’s heard on Danny’s radio. “When the truth is found, to be lies,” Rabbi Marshak tells Danny, “and all the hope within you dies.” Then he gives Danny one decent piece of advice: “Be a good boy.”

The power of the movie is its sense of mystery—it presents a puzzle you want to solve—which comes from a handful of uncanny scenes, fables within the fable. In one, Larry, who has been kicked out of his house and is staying at the Jolly Roger Motel, has a dream in which he is standing before a number-covered blackboard. The camera pulls back, and we see an equation that seemingly goes on forever. As the students get up to leave, Larry calls after them, saying, “But even though you can’t figure anything out, you will be responsible for it on the midterm.”

In another scene, we see a close-up of the Mentaculus, the book-length algorithm that Larry’s insane genius brother Arthur is constantly working on. Described as a “probability map of the universe,” the Mentaculus is a dense tapestry of arrows, numbers, Hebrew letters, and hieroglyphics.

But it’s the prelude of A Serious Man, a 15-minute opener, that sets up everything. It resembles an Isaac Bashevis Singer story; a Jewish merchant invites an old man in for a bowl of soup on a cold night. The merchant’s wife—the dialogue is in Yiddish—is convinced the visitor is a dybbuk, a demon wearing a dead man’s skin. She puts an ice pick in his chest to prove it, then sends the dying man out into the snow. According to some commentators, these are Larry Gopnik’s grandparents, who, in killing a guest, cursed their descendants. To me, it’s more like a framing trick the Coens played in Lebowski, with their use of a nameless old-time cowboy narrator. The voice from an earlier time tells you that, though set in modern supermarkets and bowling alleys, the movie is really a Western. It’s like that with the Yiddish prelude of A Serious Man. It’s a frame that tells you that what follows is a Jewish folktale, even if it’s set in Minnesota instead of Galicia. The message is the same as the message readers find in Singer’s “Gimpel the Fool”: in this world, the righteous are deceived.

A Serious Man is different from the rest of the Coens’ oeuvre—there’s something real at stake. Larry has a moral choice to make. Will he take the bribe to fix the student’s grade, or won’t he? And does it even matter? As it turns out, it does matter, a fact that takes us back to the dream in which Larry stood before the blackboard. Even though he has no idea what’s happening, he’s still responsible for his actions. The minute he forgets that and takes the cash, the phone rings and, as another midwestern Hebrew once sang, “A foot comes through the line.” We’re in the Golden Land now, but we still answer to the same old Father. “He’s a bachelor. And very angry.”

Suggested Reading

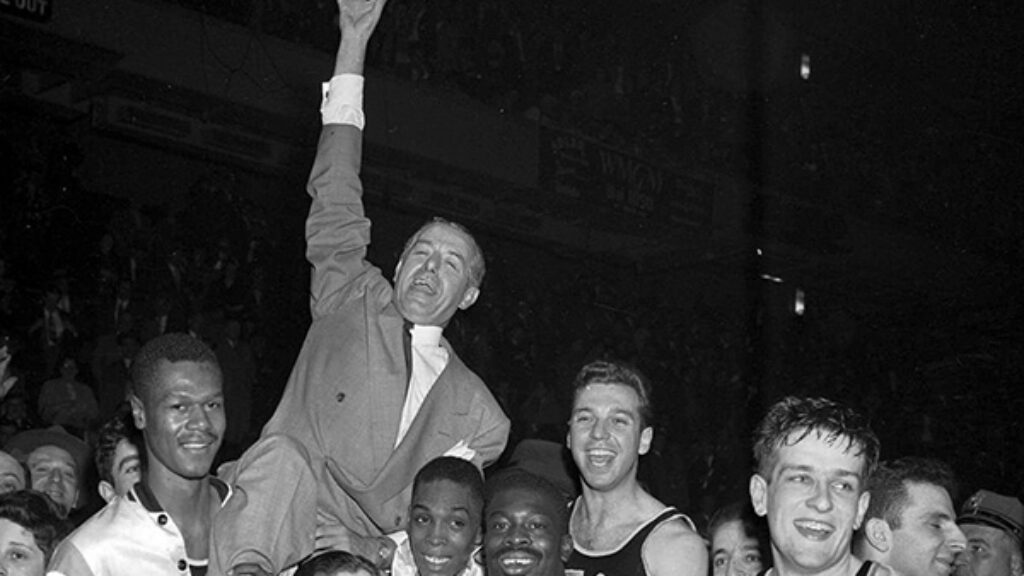

The Fix Was In

The 1951 basketball game that pitted CCNY, which fielded blacks and Jews, against the all-white University of Kentucky seemed less a meeting of schools than a clash of civilizations: old versus new, South versus North, prejudice versus tolerance.

A Foreign Song I Learned in Utah

Despite all of Bob Dylan’s subterfuges, disguises, and costume changes, he really was a child of the American heartland. Winning the Nobel Prize might actually be his most Jewish achievement.

Hollywood and Jerusalem

It would be marvelous to tell you that right after the meeting I strode indignantly to my forest-green Porsche, wheeled onto the Santa Monica Freeway, sped eastward on I-10 past Palm Springs, and didn’t stop till I got to Jerusalem. But that would be untrue.

Movies and Monotheism

At age 97, Herman Wouk returns to Moses and goes postmodern.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In