Movies and Monotheism

In 1932, an obscure Russian-born Jewish intellectual named Leon Zolotkoff wrote a novel called From Vilna to Hollywood. The protagonist is a talmudic prodigy named Hershele who abandons the dusty roads of Eastern Europe for the sunny coast of California and in the process becomes Harry Corbell, world-renowned director and owner of the upstart Corbell studio. Corbell/Hershele reaches a pinnacle of success unimaginable to his kinsfolk back home, but in the end he meets an inglorious demise, confirming the ethos of those less fortunate immigrant Jews for whom the American dream remained a groundless proposition. Zolotkoff’s novel is deservedly obscure, but in retrospect it can be said to have established the outlines of a new story type: the “Jewish Hollywood novel.” Among the sequels to Zolotkoff, we find Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust (1939); Budd Schulberg’s What Makes Sammy Run (1941); Norman Mailer’s Deer Park (1955); a number of Daniel Fuchs’ short stories, including “A Hollywood Diary” (1979); and Leslie Epstein’s San Remo Drive (2003). The Coen brothers added a cinematic version, Barton Fink (1991), drawing on the experiences of the radical playwright Clifford Odets and adding a noir stylistic touch and a grisly apocalyptic denouement.

The origins of this story type in the depths of the Great Depression are revealing, since an underlying message of many of these works is that financial success is precarious and often gained at the price of one’s soul. By the closing pages of From Vilna to Hollywood, the hero’s compromised morality and self-disgust have left him no recourse besides suicide, and an agonized Harry strides into the ocean in a scene that eerily reverses the immigration journey that started the drama in the first place, as if he is trying to become little Hershele once again.

The origins of this story type in the depths of the Great Depression are revealing, since an underlying message of many of these works is that financial success is precarious and often gained at the price of one’s soul. By the closing pages of From Vilna to Hollywood, the hero’s compromised morality and self-disgust have left him no recourse besides suicide, and an agonized Harry strides into the ocean in a scene that eerily reverses the immigration journey that started the drama in the first place, as if he is trying to become little Hershele once again.

In Schulberg’s novel, the brutally ambitious Sammy Glick abandons family and friends on the Lower East Side in a mad dash for success. According to Schulberg’s own diagnosis, Sammy Glick is somebody who, having thrown over the religious ways of his pushcart salesman of a father, has “nothing except naked self-interest by which to guide himself.” Jews are not alone in their fascination with the mythical allure of Hollywood, of course, but they have been among the most adept at crafting moral fables that decry its corrupting force. This makes sense not only because Hollywood has generated unheard-of success for legions of actual Jews, but also because it has provided a ready symbol for the Jewish experience in America, an experience that to many has seemed miraculous, perhaps too good to be true.

It is against the backdrop of this literary tradition that the significance of Herman Wouk’s charming new novel, The Lawgiver, can be measured. One must first pause in sheer amazement, of course, that the 97-year-old Wouk has written a novel at all. At a time when attention seems to be lavished on ever-younger novelists, we hardly expected to hear from somebody whose image graced the cover of Time back in 1955, when the romantic saga Marjorie Morningstar first hit the shelves. But admiration for the achievement alone itself should not distract from the substance of the work. The Lawgiver reveals a more playful and formally experimental side to Wouk than we have seen up to this point, and it recasts the conventions of the Jewish Hollywood novel in surprising ways. It may well be Wouk’s funniest novel, a reminder that back in the 1930s, his first job out of college was as a gag writer on the staff of Fred Allen (one of America’s most popular radio comedians at the time). The novel is also a fitting statement by someone whose personal trajectory from the Bronx to Palm Springs could provide the basis for a Jewish Hollywood novel on its own.

The Lawgiver takes the form of what might be called a postmodern epistolary novel. The action is related through breathless, often cryptic, communiqués, slung between characters in emails, text messages, interoffice memos, Skype conversations, and the odd snail-mail effusion. This diffusion of narrative voice among the novel’s characters shows an unexpected humility from a writer who typically speaks from a high authorial perch. And though the diction in these texts occasionally recalls the 1940s more than the 2010s, the overall narrative approach is effective at conjuring the unpredictable, fast-paced world of Hollywood. The action is set into motion by one Louis Gluck, a uranium tycoon from Australia who is also a Gerer Hasid determined to use his wealth to put a new version of the life of Moses on the screen. Though his last name recalls Schulberg’s Sammy Glick, Wouk’s Gluck could hardly be more different. If the former runs on, heedless of tradition, the latter defers to authority, specifically the authority of an aging Jewish novelist named Herman Wouk, who thus enters the novel as a pivotal character. Gluck is eager to finance his Moses movie, but he will proceed only under the condition that the script is approved by Wouk (such is the prerogative, it seems, of Hasidic uranium tycoons).

All of this is well and good, except that it turns out that this Wouk is preoccupied with his own efforts to produce a new work, which coincidentally concerns the life of Moses as well. And while the promising young screenwriter hired for the job blasts through her script, Wouk cannot progress beyond the first pages of his novel. His problem stems from a misguided conception: he is trying to write Moses’ life as a series of journal entries from the perspective of Aaron, but the humorous side of Wouk has taken over, undermining the serious tone required by the topic. Incidentally, we have learned from the novel’s preface, taken from Wouk’s nonfiction book of a decade ago The Will to Live On: This Is Our Heritage, that in actuality Wouk had been contemplating a novel about Moses ever since the early 1950s. The project has proven an insurmountable challenge, however; all he has to show for his idea are a few typed yellowed pages in a desk drawer file marked “The Lawgiver.” So even as Wouk’s current novel affirms his cultural authority—the tycoon turns to him to approve the script—it also underscores his creative limitations. Sinai is too much for him to scale. Given the accusations levied against Wouk by high culture critics throughout his career for being a “middlebrow” writer mired in popular conventions, this admission of weakness is disarmingly canny indeed.

The screenwriter whose script Wouk must approve is a plucky young woman named Margot Solovei. Her credentials include a few Art House films, boundless energy, and a deep intimacy with Torah, inherited from a father who is not merely a Hasid but the Bobover Rebbe of Passaic. Margot has absorbed her father’s teachings but cannot abide his literal understanding of the text (“‘We believe it,’ my father said about Moses’ staff that turns into a snake. ‘I can’t believe it,’ I said . . . That afternoon I packed up, went to New York and got a job.”) This rebellion enables her to discover her true calling as a Jewish American screenwriter with a properly ambivalent relationship to tradition. Her first success was an Off-Off Broadway parody of her father’s world called “Bobover Bobover.” Now she is ready to return to Torah on her own terms, as a creative writer, and her passion for the project becomes the driving force in the narrative.

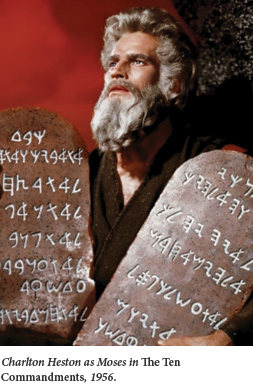

Margot is in many ways a more talented and scholarly Marjorie Morningstar—or, even better, a kind of Herman Wouk in reverse. Whereas in real life he reclaimed the Orthodoxy of his youth, she’s escaped it; whereas he’s contemplating mortality, she’s filled with guileless verve; whereas he can’t write the story of Moses, she can. In the process, Margot also succeeds in rescuing the story of Moses from Cecil B. DeMille, whose The Ten Commandments is pilloried in the novel as a counterfeit, anglicized version of the true story. Margot’s Moses is psychologically complex, a believer in God who cannot believe in himself. And her God is properly Jewish, speaking Hebrew, not pompous pulpit English.

By creating the ideal screenwriter as a rebellious Hasid, Wouk seems to be admitting something about his own famous declarations of Jewish piety (see This Is My God). As learned as he is, the truest textual intimacy is reserved for Margot, who has wrestled with the text because it formed the ground of her being. “Your roots go deep,” Wouk enviously writes to Margot in an email. “And from them you’ve drawn the fortitude and the energy charge to take on and finish your Moses.” Her script is powerful enough, indeed, to reconcile her with her father, who at the novel’s conclusion comes all the way out from Passaic to praise her screenplay. He may not know much about movies, he tells her, but he recognizes in her Moses on Mount Nebo the same “Moishe Rabenu” he taught her when she was young. In Wouk’s version of the Hollywood story, then, we discover the triumph of the Jewish American storyteller: she feels Torah in her bones, but she’s free enough from the past to recreate the tradition in her own words. In so doing, she reclaims Hollywood as a space for genuine Jewish self-expression.

But, just when it seems Wouk has surrendered his mantle to a younger, abler Jewish writer, we learn that her education was overseen not only by her Hasidic father, but by the novels of Herman Wouk as well. In a particularly deft instance of postmodern sleight-of-hand, Margot recalls in a letter to Wouk how as a schoolgirl her imagination was ignited by a racy love scene in The Caine Mutiny—and then goes on later in this Wouk novel to star in her own racy scene (with her love interest in the Australian outback). So Wouk indicates that his storytelling powers are effective, after all: Margot is better equipped for the drama of her life for having read Wouk as a girl. More generally, Wouk seems to be affirming the necessity of (his) fiction in the imagining of possibility and hence the growth of the individual.

But, just when it seems Wouk has surrendered his mantle to a younger, abler Jewish writer, we learn that her education was overseen not only by her Hasidic father, but by the novels of Herman Wouk as well. In a particularly deft instance of postmodern sleight-of-hand, Margot recalls in a letter to Wouk how as a schoolgirl her imagination was ignited by a racy love scene in The Caine Mutiny—and then goes on later in this Wouk novel to star in her own racy scene (with her love interest in the Australian outback). So Wouk indicates that his storytelling powers are effective, after all: Margot is better equipped for the drama of her life for having read Wouk as a girl. More generally, Wouk seems to be affirming the necessity of (his) fiction in the imagining of possibility and hence the growth of the individual.

Of course, Wouk’s novel strains our credulity with nearly every turn in the plot. But this may be part of the point, and it is certainly part of the fun. Wouk upholds the values of fantasy, fiction, Hollywood, and maybe of America itself as a principle of hope. In this Hollywood novel, dreams are realized, parents and children are reconciled, love blooms, and Jews triumph while still remaining Jews. Coming from Wouk, this all seems fitting, and we should be willing to suspend our disbelief, at least for the duration of the novel. Hollywood was good to Wouk, after all. His astonishing success as a writer was bolstered by hugely popular cinematic versions of The Caine Mutiny and Marjorie Morningstar (not to mention the television miniseries of The Winds of War and War and Remembrance). And he has come through it all with his God intact, perhaps more vivid to Wouk because of the epic scope of his life.

When Wouk won the Pulitzer Prize for The Caine Mutiny in 1952, Jewish American literature had yet to emerge as a coherent tradition. In the years that followed, a collection of now-famous writers such as Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, and Philip Roth came to exemplify this tradition, and their themes-alienation, ambivalence, the burden of moral insight-were carefully parsed by critics. Herman Wouk was left out of this particular party; one searches in vain for an approving nod towards his work in the writings of, say, Leslie Fiedler, Irving Howe, or Alfred Kazin. By now, however, we are less burdened by the need to make a case for Jewish American literature and correspondingly freer to enjoy the totality of his career. The publication of The Lawgiver provides an occasion to reconsider Wouk, a “popular” writer, to be sure, but also someone who has engaged and educated generations of actual readers, not only Margot, the post-Hasidic screenwriter.

As it turns out, an unpublished letter from no less an authority than Lionel Trilling reveals that Wouk has meant more to more people than one might have thought. Writing to sociologist Nathan Glazer in 1955, Trilling offered ambivalent praise of Marjorie Morningstar: “An astonishing book. Not the least astonishing part of it is that one reads it and with a kind of curious, hideous interest. Or is it just one of my secret vices that my better nature is overcome by books like this?” Wouk has fed such literary vices for generations, and now, by associating himself so thoroughly in his new novel with the dream factory of Hollywood, he signals that he has known it all along.

Suggested Reading

Robert Capa’s Road to Jerusalem

By all accounts, his own not least, Robert Capa was a womanizer, a heavy drinker, and a compulsive gambler who consistently lost his shirt everywhere from poker games at the front lines to European casinos. He was also a gifted, prolific photographer.

A Brand Rescued from the Fire

Leon Chameides has painstakingly collected his father’s writings from the fateful years of 1930s Polish Jewry, before the break-up of his family and the collapse of Jewish life in Nazi Europe.

My Father, Milton Himmelfarb

Personal reflections on the legacy of a sui generis Jewish American sociographer and essayist.

It Is Either Serious or It Isn’t

A poem by Chana Bloch is like a stone thrown deep into the well of experience.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In