Crazy Rich Sephardim

They dealt in silks, spices, cotton, jewels, carpets, opium, metals, and horses; they built buildings, docks, and railways. Their reach extended from their home, Ottoman Baghdad, across the British Empire and Qing dynasty, throughout South and East Asia and beyond. They built company towns with schools, stores, and hospitals, where they trained young men to join their mercantile ranks. They commanded their own ships and forged relations with other merchants as well as with representatives of states. Over centuries, the Sassoon family crafted a global empire, which was navigated for generations in the family’s native tongue, Judeo-Arabic.

The Kadoorie family would come to exceed the Sassoons in wealth, but their mercantile roots grew in soil tilled by the Sassoons. Four Kadoorie sons joined the migratory flow of young men who journeyed from Baghdad to Bombay, Shanghai, and Hong Kong (and well beyond) in the employ of the Sassoons. Most of these entrepreneurial merchants would never command more than middling wealth, but the Kadoories broke from the norm. Through investments in rubber, real estate, stocks, and electricity, the Kadoories built an empire of their own, which—whether through shrewdness or chance—proved more durable than the one that spawned it.

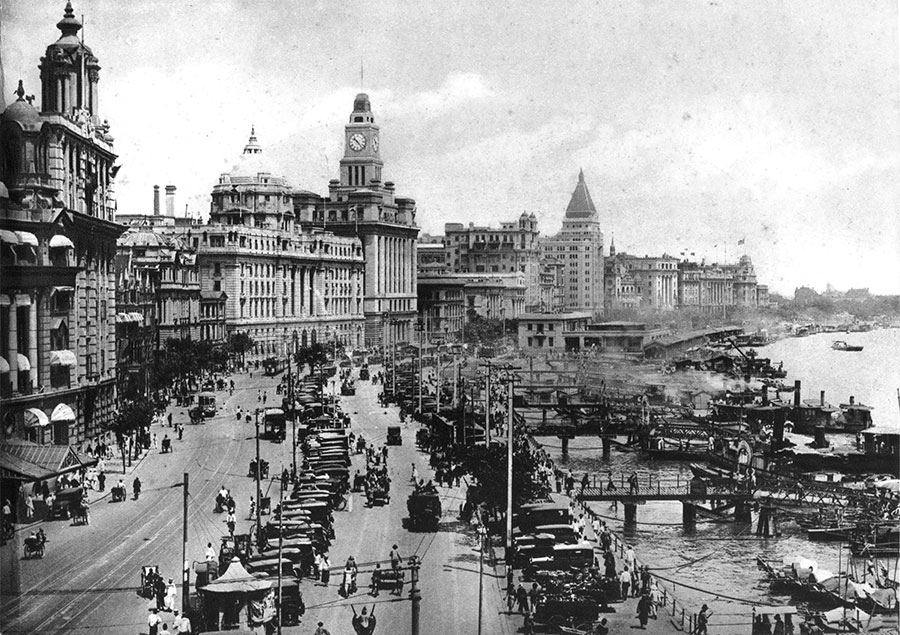

In The Last Kings of Shanghai, Jonathan Kaufman intertwines the stories of the Sassoon and Kadoorie dynasties, their foundational patriarchs, and the city in which they converged, Shanghai. It was also the city where the two families built landmark buildings (including the legendarily opulent hotels the Majestic and the Cathay), which were at the center of a glittering social scene for the city’s elite visitors. For a time, Shanghai soared along with these unusual Ottoman Jewish émigrés. In the late 19th century, its infrastructure rivaled London’s; by the 1930s, its skyline that of Chicago.

The Sassoons’ and Kadoories’ successes and failures ebbed and flowed in tandem with local, national, and imperial markets, and with the shifting tides of state power. Alas, Kaufman is not at his deftest in assessing the big picture: the historical backdrop Kaufman sketches for these “last kings” seems lifted from a 1950s history textbook. Consider his account of the initial move to Bombay (and thence into East Asia) by the scion of the Sassoon family, David Sassoon, which begins, “Through the darkened streets, the richest man in Baghdad fled for his life.” In Kaufman’s imagining, David’s departure was catalyzed by a weak Ottoman economy, an aggressive (if not outright antisemitic) imperial state, and the gradual erasure of options for the Ottoman Jewish middle class and elite. Historians of the Ottoman Empire and Ottoman Jewry have long since upended these tropes. Their studies have shown the resilience of Ottoman society and the astonishing social mobility and imperial loyalty of Ottoman Jews. Kaufman ignores decades of such scholarship in favor of outdated works such as Cecil Roth’s 1941 book, The Sassoon Dynasty.

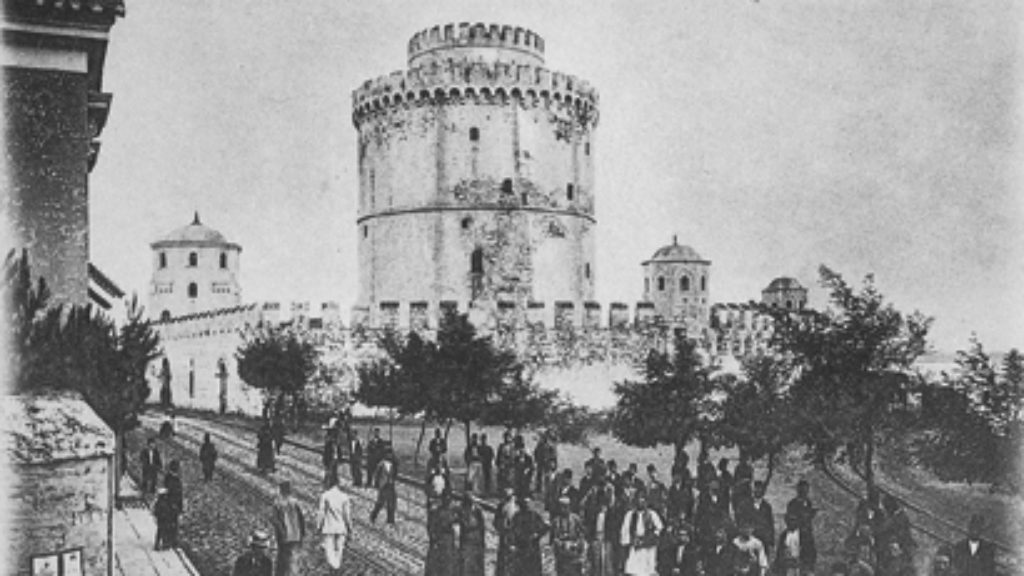

Roth’s account, like so much of his writing, was dizzyingly pioneering in its time. He was a feverish reader and wrote on topics as disparate as the Dead Sea Scrolls (on which he held a controversial and ultimately discredited view) and the dismantling of the Jewish cemetery of Salonica by the Greek municipality during the Second World War, a topic that would take decades to be treated with rigor again (all while boasting in the British Who’s Who that his chief recreation was sleep). So much about Ottoman Jewish history has been uncovered, debated, and refined since Roth’s day, with results he would probably relish but scarcely recognize. It amounts to laziness to rely upon his history of the Sassoons, which used the family to lionize British and Jewish achievement.

When Kaufman moves to the Chinese context, which he knows immeasurably better than the Ottoman (having written and reported on China for 30 years for the Boston Globe and as China bureau chief for the Wall Street Journal from 2002 to 2005), one might hope his grasp would tighten. But here, too, Kaufman’s rendition of 19th-century geopolitics is surprisingly fusty. He frames the story thus:

As Great Britain expanded across the globe through conquest, aggressive trade policies, rapid technological innovation, and harnessing the ambition and acumen of foreigners and outsiders like David Sassoon, China was becoming more closed, sclerotic, inward looking, and arrogant.

This idea that East Asian countries suffered a paucity of the derring-do and innovation that drove the West to greatness was a midcentury notion of scholars of China, who were themselves inspired by the thinking of Max Weber. My students would no longer stand for the caricature, and Kaufman shouldn’t either.

Shanghai became a so-called treaty port in 1842 when the Treaty of Nanking ended the First Opium War. As a new colonial hub, it was a city of vast inequity, with a foreign middle- and upper-class presence, growing Chinese professional and middle classes, and countless poor Chinese refugees who had fled there to escape famine and civil war. Within this maelstrom, the Sassoons and Kadoories cultivated a strategic relationship with the British that had already begun in India.

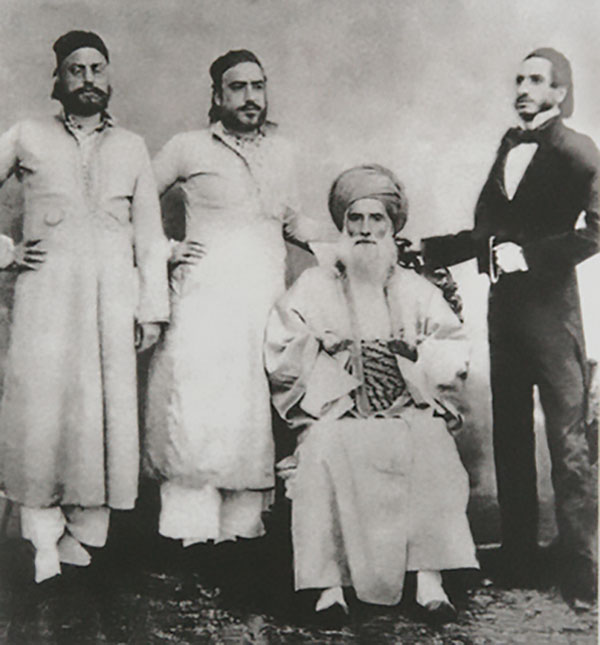

When Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, David Sassoon had taken his two eldest, Elias and Abdullah, who had been tutored in English language and history, to the Bombay waterfront to hear the proclamation:

His sons wanted to wear British waistcoats and ties. David forbade it. All three wore the clothes of Baghdad—white muslin shirts and billowing white trousers bound at the ankle. David wore his embroidered turban and dark robes. As a British military band played, the three joined the crowd shouting in English, “God Save the Queen!”

Kaufman describes this relationship with Great Britain as one of sincere fealty, but arguably for these families, as for so many erstwhile Ottoman Jewish families, the quest for European citizenship was strategic. Had the family’s reach extended to the French Empire instead of the British, it would surely have been France that the Sassoon patriarch would have called “just and kind” in appeals for citizenship.

Without a doubt, Kaufman has a flair for the dramatic. The protagonists to whom he devotes the most time (mostly men—he’s not kidding about the “kings” bit) lived very colorful lives. This is certainly true of Victor Sassoon, great-grandson to David Sassoon, and the builder of the Sassoon’s empire in China. In addition to having been a canny, Cambridge-educated businessman, Victor loved racing horses, chasing women, hosting lavish parties, and documenting his life (and lovers) with a camera. Victor’s easy charm and playboy image—he seems to have always been wearing a tuxedo with “a carnation boutonniere in his buttonhole and a silver cigarette holder poking jauntily out of his mouth”—blinded many to his business talents. He had a knack for negotiation, a feel for what would prove to be in demand, and skill at assessing and managing those around him. Victor’s friend and sometimes lover, the talented New Yorker writer Emily Hahn, wrote that Victor “liked intelligence.” This taste for (other people’s) smarts paid rich dividends.

Lawrence Kadoorie, too, is lavished with attention in Kaufman’s account. The “Cast of Characters,” with which he usefully prefaces the book, describes this Kadoorie as “sturdy, with powerful shoulders and a love for fast cars.” Someone’s eye, it seems, is on Hollywood.

Victor and Lawrence’s halcyon Shanghai days were ended by the Second World War, which brought a tide of Jewish refugees from Europe and the threat of Japanese military might. At the height of the war, around one thousand Jewish refugees reached Shanghai each month, aided by Feng-Shan Ho, the Chinese consul-general in Vienna, who granted thousands of visas to desperate Jews. Some 18,000 of these displaced souls reached Shanghai, and the brothers Kadoorie (along with an initially reluctant Victor Sassoon, whom they pressured into helping) were their greatest benefactors.

Horace Kadoorie, the youngest of the brothers, was indefatigable in helping his fellow Jews. He sponsored a youth association that offered refugee children recreational opportunities, vocational courses, and job placements. He supported a summer camp, built a school in the family’s name, and converted the family’s Rolls-Royce into a school bus. Even when wartime food shortages became severe, Horace still managed to serve refugee children one meal a day. (Later, when the family had resettled in Hong Kong, he repeated his generosity with hundreds of thousands of Chinese women, men, and children who had sought refuge in the then British-controlled city.)

The Japanese occupation of Hong Kong and Shanghai’s International Settlement in 1941, the Communists’ resurgence, and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China changed everything for the Sassoons and the Kadoories. Japanese occupation brought Shanghai to ruin and its wealthy to their knees. Kaufman’s descriptions of the occupation, including Japan’s internment of Shanghai’s Jews and the extreme deprivation experienced by these forced inhabitants, are among the book’s most original sections. While Elly Kadoorie died in Shanghai in the course of the occupation, his son Lawrence managed to use the time to dream up a way to rebuild Hong Kong. After the war, he shifted the family’s investments to that city (in which Kadoories already had a financial footing, largely through their ownership of China Light and Power) and rebuilt his family empire.

Victor Sassoon, by contrast, was forced into exile in India during the war, and subsequently compelled to turn over most of his assets—some half a billion dollars in buildings and companies—to Mao Zedong’s regime. Now, Sassoon and his empire were branded imperialists and exploiters of the Chinese people. Buildings of Sassoon’s that once housed his workers (and, temporarily, Jewish refugees) passed to Communist Party members.

The Kadoories, on the other hand, lived to experience a commercial and political reconciliation with China once Deng Xiaoping relaxed China’s reliance on collectivism. Courted by Deng, Lawrence Kadoorie invested a billion dollars in the country, and his China Light and Power electrified Guangzhou beginning in the late 1970s. These were investments most foreign businesses would have avoided. But they more than paid off, sealing the Kadoories’ place among the wealthiest citizens of present-day Hong Kong.

Like its cover, The Last Kings of Shanghai is a crude layering of snapshots, though many of the scenes they depict are fascinating. It is in awe of the luxury, landmarks, and encounters with power. In the Sassoon and Kadoorie families, Kaufman has landed on a gem of a subject. Alas, these towering familystories have yet to be written with the sensitivity and depth they deserve.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Passport Sepharad

The recent offers of citizenship by Spain and Portugal tap into a long, rich, and complicated Sephardi history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams.

Jerusalem of the Balkans

In 1911, David Ben-Gurion spent several months in Salonica and declared that it was "the only Jewish labor city in the world." Now, because of an open-minded mayor and his nationalist opponents, this formerly Jewish city is experiencing a peculiar mix of Jewish memory and anti-Semitism.

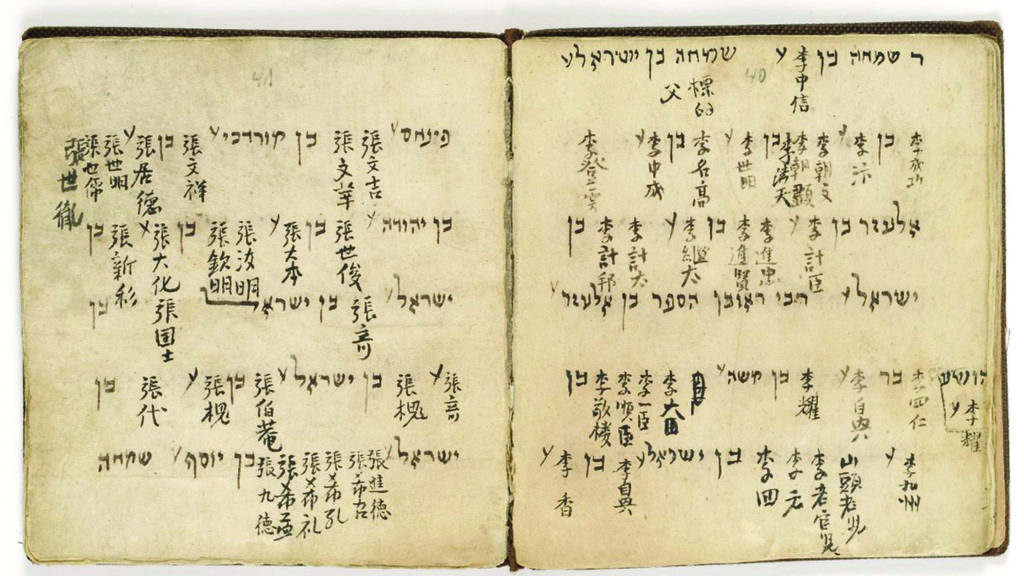

Why Is This Haggadah Different?

The Haggadah of China's Kaifeng Jews is not all that dissimilar from your Maxwell House version—but it speaks volumes about the community that produced it.

Singing Gentile Songs: A Ladino Memoir by Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi

Sa'adi Besalel a-Levi's memoir of life in 19th-century Salonica provides a rare and intimate glimpse into a lost Ottoman Jewish world. Sa'adi was an accomplished singer and composer and a printer who helped to found modern Ladino print culture. He was also a rebel who accused the leaders of the Jewish community of being corrupt, abusive, and fanatical. In response, they excommunicated him—frequently, capriciously, and, in the end, definitively—though with imperfect success.

Thomas Timberg

The flight of David Sassoon from Baghdad and Basra to Bushire perhaps and then To Bombay has not been accurately described In anything I read. It was a flight in fact I gather connected with loosing out to others in a fight for position in the provincial Governor satraps Court. One of your reader probably has done detailed research, though I imagine his scholarly gréât gréât grandson in New York Solomon Sassoon might have details.