Radical Kindness and Heroic Dogs: A New Anthology of Yiddish Children’s Literature

In Stockholm in 1978, two days after delivering his Nobel lecture, Isaac Bashevis Singer presented a top-ten list of the reasons he wrote for children. He had first shared a version of the list at the National Book Award ceremony in 1970, and it is no less an aesthetic statement than his formal Nobel lecture. Number one read, “Children read books, not reviews. They don’t give a hoot about the critics.” His tenth reason was that children “don’t expect their beloved writer to redeem humanity. Young as they are, they know that it is not in his power. Only the adults have such childish illusions.” We’ll return to some of his other reasons below.

Though Singer is intentionally absent from the book, both his top-ten list and the Nobel lecture came to mind while reading Miriam Udel’s fantastic new anthology of Yiddish children’s literature. Honey on the Page is an expertly translated, whimsically illustrated selection of lesser-known Yiddish stories and poems for children. Like the best anthologies, it is an eye-opening work of literary history, gleefully introducing a sea of lightly known authors through both their work and meticulously crafted biographical sketches. Despite its deep scholarly implications, it always remains an engaging book for families to enjoy together.

Nonetheless, this is not a book for adults to read aloud to small children. It contains exactly one poem that would amuse my son, Der Tunkeler’s (Yoysef Tunkel) “The Horse and the Monkeys,” which is full of playful rhymes like “But now a new plan makes him quiver / Giddyap! And to the river!” At five, my son is just now sophisticated enough to appreciate the logic behind B. Alkvit’s (Eliezer Blum) “The Jews of Chelm and the Great Stone.” Our trusty Chelmites carefully carry a great boulder step by step down a steep hill, only to be ridiculed by someone from another town for not simply rolling it down. Whereupon they correct their mistake:

The Jews of Chelm saw the logic in what he was saying, and they applied themselves to the task right away: all through that night, the Chelmers dragged and pushed the boulder back up the hill. . . . Many of them fell down and fainted under the heavy burden, but just as the day began to dawn, the boulder lay once more in the same spot on the hilltop where they had found it the previous morning.

And so “at last they could roll the stone down gently, very gently, from the hilltop,” and the stranger—and my son—laughs again. But most of Udel’s selections are aimed at older children and adolescents. They are for kids like Joseph, the boy in Judah Steinberg’s “Questions,” who bugs his mother with questions about injustice: “Why do we lie on white pillows while the geese lie on the ground? . . . And why does the sheep go around naked while my suit is made from his wool?” The mother is silent, so the boy takes a notebook from his pocket and writes down his questions. “‘When I grow up, I myself will find the answers to these questions!’” In “What Izzy Knows about Lag Ba’Omer,” the questions are about religion, history, and Jewish pride. Udel writes that in selecting these stories from hundreds of anthologies, individual storybooks, and periodicals for children, “I’ve envisioned a child reading, with sympathetic and curious adults nearby,” and chosen stories and poems that “taught me something new, reframed what I already knew, charmed me, and astonished me.”

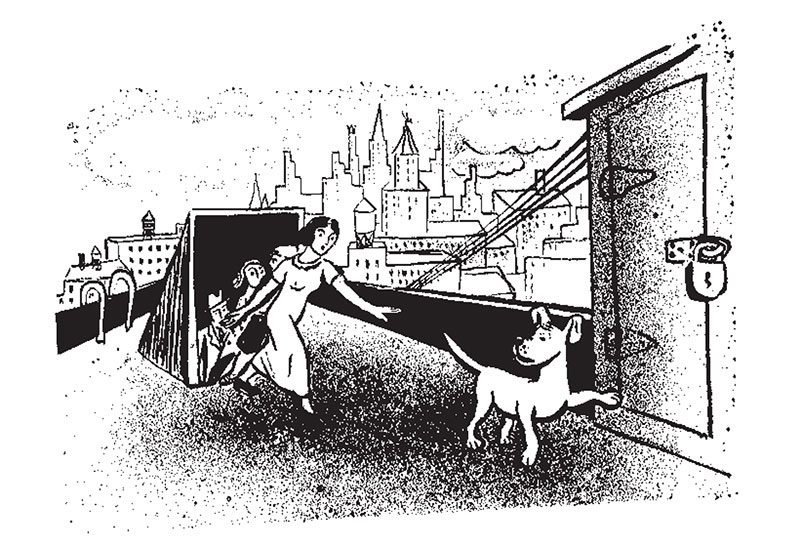

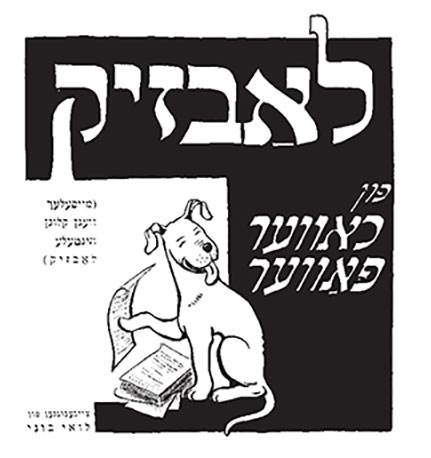

In some cases, the charm is obvious. One of the most beloved figures in Yiddish children’s literature is Khaver Paver’s (Gershon Einbinder) Labzik, the socialist dog. In “Labzik and the Strike,” the family patriarch, Berl, gets trapped on the roof of a skyscraper by his boss and a couple of gangsters:

[Labzik] sniffed the roof, sniffed and sniffed until he bumped into some kind of small enclosure with a locked door. . . . He knew already that Berl lay there, because he could hear sighs from inside. But what would scratching the door accomplish, when it was so tightly locked? Labzik thought about it, turned himself right around, and raced down all thirty flights of stairs.

Like Lassie or Tintin’s Snowy, Labzik runs for help. Some of the other stories and poems will require more historical imagination and explanation on the part of the grown-up to re-create their charm. After all, unlike Singer’s stories, most of the works in Udel’s anthology were not crafted for an American audience. In other cases, to fully appreciate the stories, the adult will have to strive to reimagine themselves as a child, undo the distance of years and experiences. That is, it is the child who will have to explain.

But what of Singer’s top-ten list? Do these popular children’s stories vindicate his view of young readers? He’s certainly right that children do not read to rid themselves of alienation, and “they still believe in God, the family, angels, devils, witches, goblins, logic, clarity, punctuation, and other such obsolete stuff.” Witches and goblins are absent from the anthology, but there is plenty about family and God. Even ardent secularists, Udel explains, wrote stories about the holidays and transmitted “an awareness of tragic, hopeful, and resilient dimensions of Jewish history.” Indeed, the volume opens with Yaakov Fichmann’s “A Sabbath in the Forest,” in which Lipe the tailor is rewarded for his piety with miraculous, lifesaving Shabbos shelter and a feast that reminds him of his wife’s home cooking. He never tells her or anyone of the experience, but when at their Shabbos table, his wife would say, “Time for the fish, Lipe—it has the taste of paradise!” he would smile and reply, “Yes, yes, my Nechama! I’ve known for a long time that your Shabbos cooking has the true taste of paradise.”

Reading Udel’s anthology, it seems to me that Singer’s most far-fetched statement about child readers is that “they have no use for psychology.” It is true, of course, that the ambivalent, ruminating protagonists of Singer’s novels would be hopelessly adrift in a children’s book. Time and again, however, the heroes of Udel’s stories come to terms with psychologically difficult aspects of childhood, like younger siblings (“Evie Gets Lost”) and difficulty learning (“The Alphabet Gets Angry”).

Then there is the book’s centerpiece, Zina Rabinowitz’s astounding story “The Story of a Stick.” Easily the longest entry, Rabinowitz weaves a multigenerational family saga of European Jews confronting questions of faith, salvation, and lineage. We follow the family through world wars, from Germany to Palestine to France, to Warsaw, and, ultimately, to Israel. A quasimystical, talismanic stick engraved with a verse from the Torah is acquired, then passed from generation to generation, with each recipient needing to uncover the stick’s meaning for themselves. In the last of the story’s 16 short chapters, a child of this family has survived the war and is celebrating Tu Bishevat at a children’s village in Israel. In a trembling voice, he calls out:

“I, Ya’akov Guttmann, the son of Benjamin Guttmann, the grandson of Joseph Guttmann, and the great-grandson of Reb Jacob Guttmann of Frankfurt-am-Main, am now fulfilling the instruction of my father to do what is engraved upon this stick: I am planting it together with a new sapling in honor of the New Year of the Trees.” . . . When he covered the hole with the dug-up earth, the tip of the stick could be seen . . . with its last six letters of the carved verse spelling out, “and you shall plant.”

“The Story of a Stick” is loving and also heartbreaking, an adolescent version of The Family Moskat that, for all his mastery, Singer could never have written.

Udel is an excellent translator. Each story and poem sounds like it was originally written in English, though perhaps the English is sometimes a little too clear and uniform. With this many authors, the translator’s biggest challenge becomes differentiation. Only the modernist stylists (Ignatov, Kulbak, Asch, Shteynbarg, and Der Tunkeler) truly stand out as having distinct voices. Likewise, Udel’s selections are wide ranging and surprising. On balance, the decision not to include any stories from Singer was correct since they are so well known and widely available. However, it does deprive us of the chance to reread them as part of a broader movement. It also means that the anthology is slightly less good than it could have been but more interesting as an act of literary history.

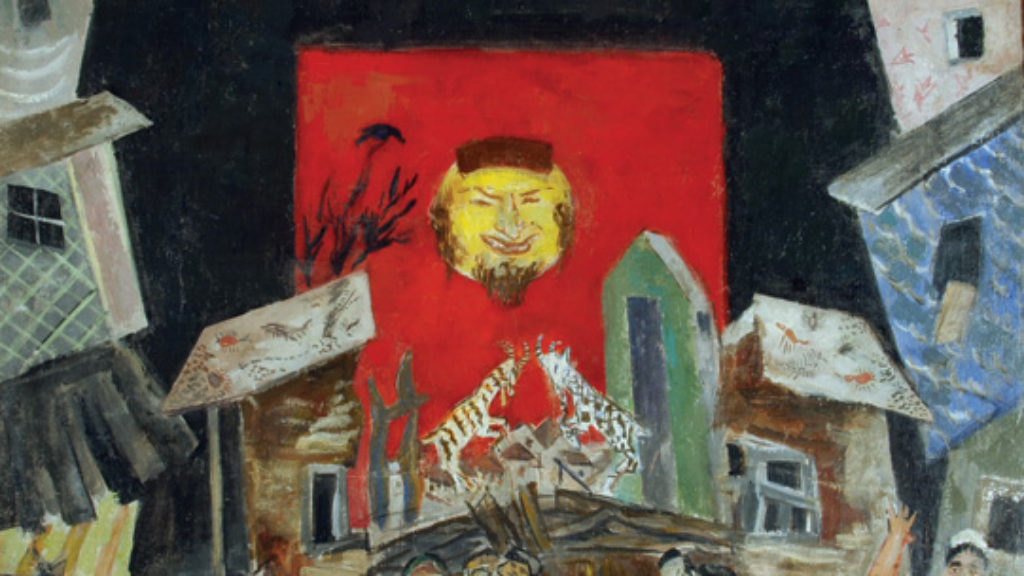

Many Yiddish picture books were illustrated by modernist artists, with extraordinary typography and cutting-edge design, and although Honey on the Page contains lovely original art by Paula Cohen and a few illustrations from the original Yiddish texts, many of the more dynamic combinations of Yiddish words and images from the original books are notably missing. Udel notes in the introduction that children’s literature was “a high priority” in the Soviet Union, but this fails to capture the emphasis placed on producing beautiful objects. The books mattered. A first edition of Mani Leib’s rhymed children’s story “Yingl Tsingl Khvat,” published in Saint Petersburg in 1919 with luminous illustrations by El Lissitzky, sold at auction for $5,500 just last month. Still, NYU Press has produced the kind of elegant, well-illustrated book that children will want to open and reopen.

At the end of his Nobel prize lecture, Singer described “the Yiddish mentality” to the Swedish academy (in Yiddish):

It does not take victory for granted. It does not demand and command, but it muddles through, sneaks by, smuggles itself amidst the powers of destruction, knowing somewhere that God’s plan for Creation is still at the very beginning.

By the time Singer made that statement, the traditional folkways of Yiddish life had been breaking down for over a century. The texts that comprise Udel’s anthology are a window into what came after. In the great tradition of the Yiddish Haskole (Enlightenment), these poems and stories, many crafted by pedagogues and other professionals in the field of children’s literature, were meant to serve as part of the child’s development. They weren’t lesson plans but material for children to explore by themselves.

“Again and again,” Udel writes, “these stories illustrate the disruption posed by radical kindness—a powerful form of social intervention that children can enter into fully and even initiate on their own.” Udel’s “radical kindness” is a compelling framework, one that aptly captures the universality of these stories. But we should also go a step further and accept the full implications of Udel’s anthology. If there was such a thing as a “Yiddish mentality,” if it still existed in 1978, then it existed in large part because of stories like these and what they taught these earliest readers. Ironically, this means that Singer’s last remaining reason for writing for children—”Children don’t read to find their identity”—was wrong.

Suggested Reading

If God Wills It, a Broom Can Shoot

“Are you really intending to raise our kids,” my wife Tali asked me one Saturday afternoon after our Shabbes lunch, “in a world that doesn’t have Harry Potter in Yiddish?”

Talmuds and Dragons

Like the medieval literature to which it pays homage, The Inquisitor’s Tale weaves in supernatural events and divine interventions, mythic beasts and wild peoples, and even entrées into medieval theology, all liberally peppered with puns and potty humor.

Playing the Fool

Of the many varieties of anti-Semitism, or anti-Judaism, that have plagued the Jews over the centuries, two recurrent general patterns can be identified by the holidays that celebrate triumphs over them: Purim and Hanukkah.

Culture and Education in the Diaspora

After 1948, Ben-Gurion strongly urged young American Jews to make aliyah. In 1951, Hayim Greenberg, head of the Jewish Agency's Department of Education and Culture, came to Jerusalem to argue for the dignity of Jewish life in the diaspora—in Yiddish.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In