The Joy of Being Delivered from Jewish Schools Results in a Stiff Foot

With extraordinary chutzpah and deep philosophical seriousness Solomon ben Joshua of Lithuania renamed himself after his medieval philosophical hero Moses Maimonides and became Solomon Maimon (1753−1800). Maimon was arguably the most brilliant and certainly the most controversial, even disreputable, Jewish philosopher of the late 18th century. He embarrassed Moses Mendelssohn (who asked him to leave Berlin), provoked Kant, and inspired Fichte, among others.

In his autobiography, Salomon Maimons Lebensgeschichte, published in two volumes in 1792 and 1793, Maimon told the picaresque story of his life with candor, humor, and occasional exaggeration. His literary exuberance notwithstanding, Maimon’s autobiography is a key source for understanding traditional Jewish life in Lithuania, the early Hasidic court of the Maggid of Mezheritch (of which he drew a somewhat acidic portrait), and the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) circles of Berlin, through which Maimon passed, as he himself characteristically remarked, “like a comet.” Maimon’s account here of his education as a boy is an early, influential, and characteristically funny version of the Haskalah critique of the brutality and irrationality of traditional Jewish education.

Despite its influence, popularity, and frequent anthologization, Maimon’s autobiography has not been translated into English since the 19th century and has never been translated into English in full. The present text is taken from the forthcoming translation by Professor Paul Reitter, professor of German literature at The Ohio State University and a frequent contributor to these pages.

My brother Joseph and I were sent to school in Mirz. My brother, who was about twelve at the time, lodged with a famous schoolmaster named Jossel. This man was every young person’s nightmare, the scourge of God. He handled his charges with an unheard of brutality, whipping them for the slightest offense until the blood flowed, and not infrequently tearing off ears and gouging out eyes. And when the parents of his unfortunate victims came to complain, he would hurl at them rocks or whatever was at hand; who the parents were didn’t matter. With his walking stick, he would then proceed to chase them out of his rooms—all the way back to where they lived. His students became either dunces or great scholars. Only seven at the time, I was sent to a different schoolmaster.

There is one anecdote that I must tell here. In part an illustration of deep brotherly love, it should also be seen as expressing the mentality of a child hovering between the hope that he will find relief from a misfortune and the fear that the misfortune will become worse. One day, I came home from school with eyes that were red from crying (I certainly had had good reason to cry). My brother noticed my eyes and asked what had happened. At first, I didn’t want to answer him, but, finally, I confided: I had been crying because we aren’t allowed to gossip. My brother understood me quite well. He was so outraged that he wanted to set my teacher straight. I asked him not to do that, however, since the teacher presumably would have punished me for gossiping.

Now I must relate something about the general condition of Jewish schools. The school is commonly a smoky shack in which students are scattered around; some on benches, others on the dirt floor. With a filthy shirt on his back, the teacher sits on his desk commanding his regiment. All the while, he holds between his legs a bowl of tobacco, which he works over into snuff with a pestle as massive as the club of Hercules. His assistant teachers conduct drill sessions in their own corners of the room, each one ruling over those in his charge just as the teacher himself does: despotically. Of the breakfasts, snacks, etc. that the children bring with them to school, the teachers keep the lion’s share for themselves. Indeed, sometimes the poor boys get nothing at all. And if the boys want to avoid facing the wrath of these tyrants, they won’t complain. Here children are locked up from morning until evening. They have free time only on Fridays and on the afternoon of new moon days.

As to the actual curriculum, at least the Hebrew alphabet is studied quite properly. By contrast, the method for acquiring the Hebrew language is very odd. Teachers don’t go over the principles of grammar, which, instead, students learn ex usu—that is, by translating the Holy Scripture, much like the common man who through normal use learns the grammar of his mother tongue in only an incomplete way. Nor is there a Hebrew dictionary. Students begin right away to interpret the Bible. Since the Bible is divided into as many sections as there are weeks in the year (so that students can read through the Books of Moses, as they are read every Saturday in synagogue, in a year), each week students interpret several verses from the beginning of the section for that week, making every possible grammatical mistake as they proceed. But there is no good alternative here. For the students’ Yiddish-Polish native language is full of grammatical deficiencies, and so when Hebrew readings are glossed in the students’ native language, the Hebrew they learn through it will naturally be of the same poor quality. Thus, students gain just as little knowledge of the Hebrew language as of the Bible’s content.

In addition to that, talmudists have buried the Bible under all manner of strange ideas. The ignorant teacher confidently believes that the Bible can have no meaning other than the ones these explicators give it, and his students are compelled to share this belief, with the result that the correct interpretation of words necessarily gets lost. For example, where the first Book of Moses reads, “Jacob sent messengers to his brother Esau,” talmudists like to claim that the messengers were angels. Now while the Hebrew word “malachim” can mean, to be sure, both messengers and angels, these miracle-chasers opted for the second meaning simply because the first doesn’t suggest anything miraculous. Students, in turn, come to believe firmly and rigidly that malachim means nothing other than angels, and thus the primary meaning of messenger gets completely lost for them. It is only by studying on one’s own, and by reading Hebrew primers and philological commentaries on the Bible, e.g., David Kimchi’s and Ibn Ezra’s (which just a few rabbis use), that bit by bit one will be able to achieve a correct understanding of the Hebrew language and work toward sound exegetical practices.

Children are condemned to such a hell at precisely the time when their youth is in full bloom. So one can easily imagine the excitement with which they look forward to getting out of school. On high holidays, we (my brother and I) were picked up and brought home. During one of those trips, the following event—which would prove to be of crucial significance for me—took place. My mother had come before Pfingstfest [Whitsuntide, the week leading up to the celebrations held on the Sunday following Easter Sunday] to the town where we were going to school, because she needed to buy various things for her household. Afterward, she took us home. Being freed from school, coupled with the sight of the beauty of nature, which at this time of year wears its finest attire, made us so ecstatic that we came up with all kinds of reckless ideas. As we were approaching our hometown, my brother leapt out of the wagon and ran the rest of the way on foot. I wanted to copy his bold jump, but I wasn’t strong enough. I tumbled down and landed next to the wagon in such a way that my legs wound up between the wheels, one of which ran over my left leg, crushing it horribly. They brought me home half-dead. My foot seized up and was completely immobile.

A Jewish doctor was consulted; he hadn’t, to be sure, studied medicine at a university and earned a regular degree. Rather, he had acquired his medical knowledge by working under a doctor and by reading some Polish medical books. But he was nevertheless a very good practical physician who had successfully healed many patients. He had, he said, no supply of medicine, and the nearest pharmacy was twenty miles away. Thus he couldn’t prescribe a cure using his normal method. In the meantime, however, an easy household remedy should be employed. Someone should kill a dog and insert the seized-up foot into it. Repeating this several times would definitely bring about some relief. His order was followed, with the success that we had hoped for: After several weeks, I could move my foot and put weight on it. Gradually, moreover, my foot healed completely.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Succession, Secession!

The notion of zera kodesh, “holy seed,” appears only twice in the Bible, both times in reference to the people of Israel as a whole. For Hasidim, however, it has a more restricted meaning.

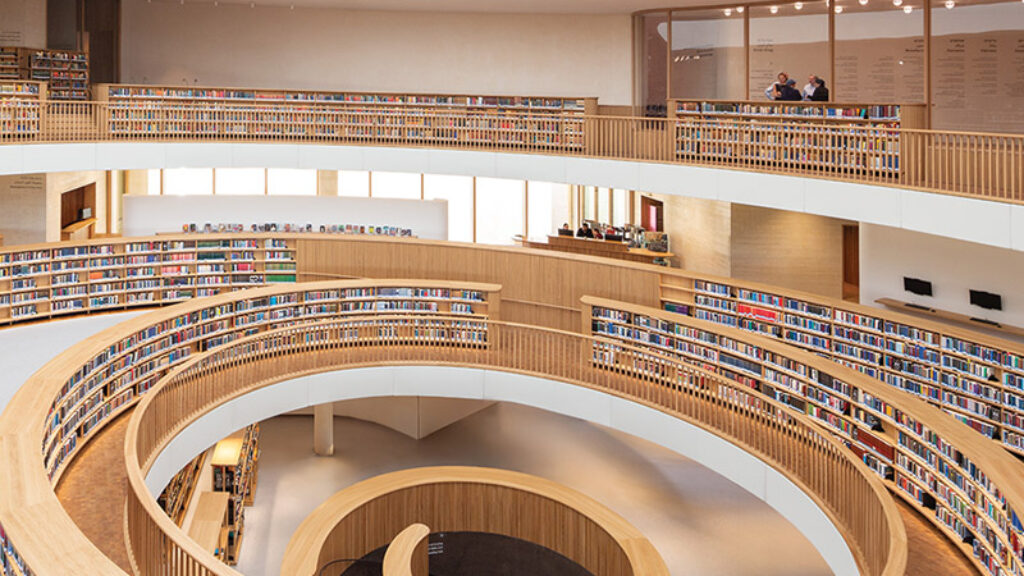

This Great House

Israel's new National Library is the most architecturally exquisite building erected in the history of the Jewish State. Like its predecessor, it’s also an excellent place to “hock” about books and ideas.

Brave New Bavli: Talmud in the Age of the iPad

The Talmud was hypertextual before we had the word. ArtScroll's new app is only the beginning.

What a Friend We Have in Jesus

A new crop of books about Jesus, by Jews and for Jews.

Martin Berman-Gorvine

Ach, ze good old days!