Working One’s Way Out

Half inch crust of frozen snow on hills facing south toward Pownal Valley and the Berkshire hills beyond—blinding blue of winter sky and sun glare on the icy crust—sensations of exposure and abandonment—desolation of

the sublime.

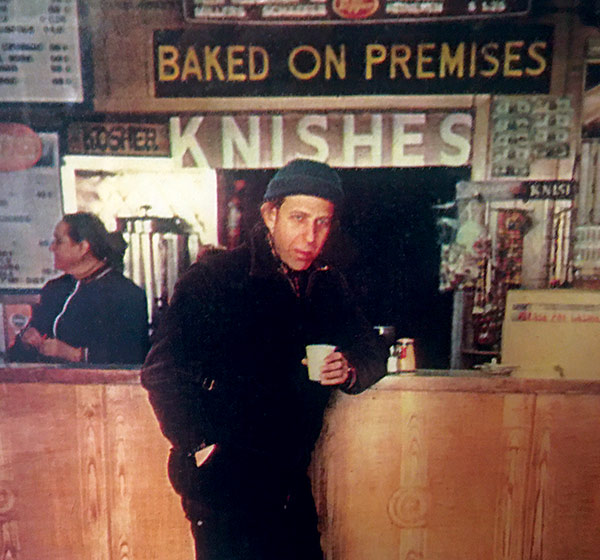

—Steve Kogan, Winter Vigil

There was a time when a senior editor at a good publishing house who read a manuscript that began with such a sentence and didn’t falter for the next two hundred pages would have snapped it up at once. This was before he or she would have said, “I loved the book. Let me consult my colleagues about it.” Before “My colleagues are enthusiastic. We’re going to run it past our marketing department.” Before “We’re terribly sorry, but marketing says memoirs by unknown authors don’t sell.” Before 20 such rejection letters were received by Carol Rusoff, Steve Kogan’s widow, until in 2018, three years after his death, she published Winter Vigil at her own expense.

When I first read Winter Vigil over a year ago, I was as swept away as that once-upon-a-time editor might have been. I hadn’t read any contemporary writing as good in a long time. I hadn’t known Steve Kogan could write like that. I hadn’t, it turned out, known very much about him.

The two of us were classmates at Columbia in the late 1950s and early 60s, first as undergraduates and then as graduate students. I don’t remember if I knew Steve as an undergrad, although we were both English literature majors, and Winter Vigil describes courses that I took. We certainly didn’t sit in the same classes in graduate school because I didn’t go to any during the year in which, on my way to dropping out of academic life, I picked up an MA on the strength of a thesis written in utter solitude. To this day, I smile sheepishly when someone says, “You were at Columbia in the early 60s? It must have been wonderful going to lectures by men like Lionel Trilling and Jacques Barzun.” I never attended a lecture by either man.

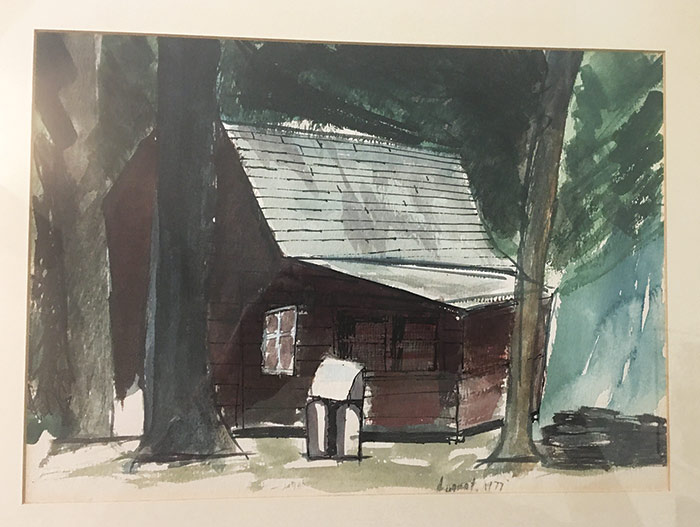

In this respect, I was different from Kogan, who gladly took what formal studies had to offer and writes about Trilling and other professors appreciatively. In the end, though, he dropped out too. “I have come here,” he tells us, recalling his stay in the cabin he built overlooking Pownal Valley,

from libraries and lecture rooms and the dread that came over me at twenty-nine that I was heading straight for death in the academic world, with the doctorate as the sealing of the tomb. On a winter break in ’67, I walk along the edge of Candlewood Lake in Connecticut early one morning and hear the ice crack and shift beyond the shore. I think about my divorce after six years of a graduate school marriage and about my students’ papers and my unfinished dissertation on Elizabethan theater and decide I’ve had enough. Two months later, I’m living among radicals in Oakland and losing myself in one sixties’ scene after another from California to the Lower East Side, ending up in a “commune” just above the Southern Vermont Apple Orchards, where I finally come to rest.

By the time all this had happened, I hadn’t seen Steve for a while. Before that, though, we had gotten to know each other through a circle of mutual friends in which we found ourselves together on many occasions.

The ones I recall best were the musical ones. These were nights at off-campus apartments in which people drifted in and out while four musicians played and sang and put down their instruments and picked them up to play some more. There was Art Rosenbaum from Indianapolis, a wonderful banjoist with whom I had biked around Brittany the summer after our college graduation; Art went on to become a professor of art at the University of Georgia and a painter of colorfully rhythmic, WPA-style canvases and murals. There was Tam Gibbs, who came from California and played a funky blues guitar. (He later became the disciple of a Chinese tai chi master, fell unhappily in love with the master’s daughter, and died from either suicide or drink, depending on whom you heard it from.) There was a fiddler, Brooks Adams, a tall, thin, quiet young man directly descended from John Adams, the second American president. And there was Kogan on the mandolin. When the four of them got up a full head of steam on “Swannanoa Tunnel” or “Old Joe Clark,” there was no more drifting out.

For sheer volume, a mandolin can’t compete with a banjo or violin. I remember Steve looking down from time to time at his instrument as he played, as if seeking reassurance from it that they were being heard, and looking back up with a nod and shy smile. Perhaps I imagined his feelings. But the shyness was real. You felt it when you spoke with him. He wasn’t a stutterer. He didn’t stumble over words. But the words, when they came, seemed to come with difficulty, as if there were some impediment in their way. As if they had to be searched for in a place he had no easy access to, dredged up from the depths of silence.

Silence, Kogan tells us, was the “root experience” of his childhood. It emanated from his mother, a “long-haired, beautiful woman inhabited by the past [who] lived in a state of low-intensity possession, as if she were a daily medium for ghosts,” communing with her lost youth in Ukraine and talking aloud to the photographs in her family albums, most of relatives killed in the Holocaust. At such moments, she was “nearly motionless, lost inside her memories, absorbing me into her world. . . . Identifying with my mother’s moods, I felt threatened by change of any kind, and beginning with those afternoon photo séances of hers, stillness and passivity became a way of life for me.” Writing in English about her, and about being the only child in an immigrant home whose main languages were Russian and Yiddish, “kills the emotions and events I am describing,” Kogan tells us, “by translating them out of their living context, making me want to be silent—in other words, to be with mother and remain a child.”

Carol Rusoff has written me that Kogan originally thought of calling Winter Vigil “Queen Lear in Brownsville,” which is now the title of the book’s fourth chapter. Indeed, Lear goes mad, and Kogan describes his mother as “gently, almost spiritually psychotic.” Yet read Shakespeare’s play, and there is more to it than that. “What shall Cordelia speak? Love, and be silent” are the first words spoken by Lear’s youngest and, in the end, only remaining daughter. And in the play’s last act, Lear, now a crazed old man, says to her, “Come, let’s away to prison. / We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage. . . . So we’ll live / And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh / At gilded butterflies.”

We two alone. Long parts of Winter Vigil are about a New York childhood that, though crammed with model trains and airplanes and Erector sets, was dominated by a mother who, when not in one of her withdrawn states, sang her son Russian songs, and read him Russian fairy tales about snow maidens and talking animals and forest witches, and spent days with him at her side making jams and cooking borscht and sewing and stuffing little pouches of chicken skins, weaving around them a magic spell that he was unable to cast off no matter how many Brooklyn streets he rode his bike down, or pink rubber “Spaldings” (was it only in Manhattan that we called them “spaldeens”?) he fired at strike zones chalked on the walls of buildings, or CO2– propelled rockets he and his friend Marty Maisel shot into the air with seltzer cartridges. Everything about his mother, Kogan writes, “seemed bewildering, and since she was both oppressive and detached, being in her presence was like being absorbed into a prison and an endless distance all at once.”

Only partly balancing her was Kogan’s father. An outgoing man, he was a connection to the world outside the home, though in it, Kogan writes, “He left me exposed to mother in far too many ways” and was himself subjugated by “his spirit of sacrifice to her [which] led me into being absorbed by her illness, so that throughout my childhood I had the vague sensation of having been born somehow ill—some vague but permanent condition of never being well.” Originally hailing from Kishinev, Kogan’s father added Hebrew to his Russian, Romanian, and Yiddish while living in Tel Aviv as a construction worker in the 1920s before coming to America, where he worked in an aircraft plant and then as a salesman. A combative and adventurous spirit (he once cowed a ruffian in a bar by threatening to slash him with a water pitcher he smashed and another time came home from a walk in the park with a snake he had caught), he was a lover of classical music, an ethnic Jew who hated religion and wouldn’t let his son have a bar mitzvah, a Zionist with a liking for Arabs, and an ardent Communist until devastated by the party’s post-Stalin revelations. Yet he was also given to dark broodings. “Sometimes,” Kogan writes,

I think that this troubled side of him was his deepest bond with my mother and that in some sense he too was disturbed, not in any conventional way, and certainly not in the unbalanced condition of my mother, but nevertheless disturbed, so that both of them appear to me as orphans of the storm. I know that he used her illness as a way of hiding his own insecurities, which were only proper to himself (the current term is “co-dependency”); yet I also know that he loved her, as best he could, that they shared an exquisitely personal sense of loss and nostalgia, and that he was convinced that if he left her, she would simply drown, that no amount of family support could rescue her, and that in some strange and fatal way, he was responsible for her life. It is at this point that their relationship becomes so filled with darkness that I no longer know what to think.

Loss and nostalgia. In reading Winter Vigil, I felt them too.

That’s not surprising. Kogan and I were born within a year of each other. Winter Vigil’s pages are full of the New York and America that we grew up in and went to school in and left school in. The Erector sets, the model airplanes, the cap pistols, the stamp collections, the Good Humor man and the knife grinder’s truck, the automats, the telephone numbers that started with Academy 2 and Havemeyer 4, Life and Junior Scholastic magazines, the Yankee, Dodger, and Giant games traveled to on the IRT and the IND and the BMT in cars packed with fans like troop carriers—“Friends of mine who grew up in Brooklyn,” Kogan writes, “remember seeing ballplayers coming out of the subway along with the people”—the summer bungalow colonies in the Catskills: childhood!

And then the high school years with their discoveries. Of a world beyond the confines of home, neighborhood, and early schooling. (Kogan escaped Brownsville by going to Manhattan’s High School of Music & Art, one of five special New York City schools that gave admission exams, while I fled my Jewish day school for another of the five, the Bronx High School of Science.) Of intellectual and aesthetic experience—the books, the museum visits, the concerts, each capable of making you feel you had just begun a new life. Of girls and the torments of dating. (“I would end up standing,” Kogan writes about the carless New York boy’s duty to escort his date home, “on some God-forsaken avenue near Utopia Parkway at two in the morning waiting for a bus to take me to a train.” He forgets to mention that the night was bitter cold and the bus ran once an hour.) Of America itself, the unknown continent across the Hudson with which Kogan “finally made contact . . . coming into my own, coming down to earth” on a summer job with black migrant workers on a chicken farm in New Jersey, just as I did the summer I baled hay and drove fence posts at an outpost of integration in the Jim Crow South in the company of left-wing organizers, early civil rights activists, southern Negroes, and Tennessee hillbillies.

And then Columbia and the 60s and the call of the road. Kogan writes:

By 1968, I had driven, hitchhiked, flown, and taken trains and buses around the country a dozen times or more—once in late winter with a couple of friends in an old New York City taxi cab to sell to an Indian in Butte. He met us on a snow-covered street with a hundred and fifty silver dollars in a sack. We had a steak dinner at nine in the morning, bought some old work clothes in a general store . . . and we headed out of town—Mark in hiking gear, Jenkin in sneakers reciting Whitman while standing in a foot of snow. Somewhere in Idaho, they hitched a ride and caught a freight train to Chicago, freezing all the way. I went south on a passenger line to Salt Lake City, sleeping the night before in the Pocatello railway station and in the morning looking through my railway window at the winter vastness of the west—gray sky turning brilliant blue in Utah, where I took a jet that night to make it back in time for my doctoral exams.

Had I not, too, stood on a street corner in a black neighborhood of Baton Rouge with my friend Nicky Goldman and a New York abstract expressionist painter whose name I’ve forgotten, auctioning off an old semiautomatic Dodge that sprang an oil leak and died in billows of smoke on our way back from Mexico City, the proceeds from which barely paid for three Greyhound tickets to New York? Mark and Jenkin! That’s Lennie Jenkin and Micky Solomon, who writes a foreword to Winter Vigil—Micky of the golden, nearly shoulder-length locks (now Mark and bald), who drew jeers from the passing cars that wouldn’t stop for him, his wife, Kathy, and me when we were marooned for a day outside Lordsburg, New Mexico, while trying to thumb our way to California.

That was a continuation of a second Mexican adventure. We had agreed to meet in Tehuantepec because it was both on the map and in a Wallace Stevens poem, and we had set aside three days to rendezvous there in the marketplace at five in the afternoon, after which, if I or they didn’t show up, they or I would move on. I had worked on a banana boat that left me off at the Panama Canal on its return trip from Ecuador and hitchhiked most of the way to the Mexican border, which I only reached at noon of the third day because I had lingered to climb a volcano in Guatemala, and all the way I leaned forward in my seat and said, “Más rápido, más rápido,” to the taxi driver, who got me to Tehuantepec at 4:45, a straw sombrero on my head and a dagger with the words Amor Perdido tucked into my belt, feeling like Phileas Fogg in Around the World in Eighty Days.

The 60s and the lure of a life on the land! After studying in England for a year, returning to New York for my MA, spending half a year in Israel, teaching for another year at a black college in Alabama, returning again to New York, and heading out for a while to California, I bought land in Maine, on which I planned to live in a log cabin. This was about the time that Kogan, so Winter Vigil tells us, built a cabin looking out on Pownal Valley, with a view of which the book begins. A few months later, I married. My wife and I spent the summer of 1967 tenting on our land while the dust from the Six-Day War was settling over the Middle East, and in 1970, just in time to round out the decade, we moved to Israel. After that, my life and Kogan’s, which had in some ways run parallel, took different directions.

I was talking about nostalgia the other day with my eldest daughter. She’s an expert on it. When she was six, she once burst into tears because she realized she would never again be five. “It’s not the Erector sets or the telephone numbers,” she said. “It’s being young. My generation will feel nostalgic for Lego and landline phones.”

She was right, of course. I romanticize. Those years weren’t quite like that. Our memories pass through a filter of forgetfulness that coats them with colors they may not originally have had, that may derive from stories told long afterward to ourselves or to others, from a self-image we wish to promote, even from books we have read. Kogan speaks of the influence of Kerouac. Who of us wasn’t exposed to it?

Still, I told my daughter, there’s a difference. Erector sets came with screwdrivers, wrenches, nuts, and bolts. They prepared you for a world of real tools. And “even the loss of supposedly trivial things like the names of subway routes or telephone exchanges,” as Kogan writes,

has repercussions in the way we come to feel and live our lives. The substitution of “the number 1,” “the number 2,” “the number 3” for names of subway routes or of area codes for neighborhoods on the old telephone lines destroys a small but identifiable sense of community and leaves an abstraction in the place of a living thing. And with the loss of all these focal points of human association comes a weakening of social ties, so that when we’re faced with new tasks and responsibilities, there’s less and less to rely on in the way of continuity.

I agree. But one of the challenges of growing old is the need to distinguish between nostalgia and valid social criticism. One doesn’t want to be a grouchy old man. Things may seem to have been better when we were young—but were they better because they were better or were they better because we were young?

You can argue either side of it. The thing about social change, especially when it’s technologically driven, is that the good always comes with the bad. It’s a package deal. Modern medicine can cure an array of once untreatable diseases, but where are the days, remembered by Kogan and me, when family doctors routinely made house calls and came when you needed them? The automobile shrank distances, relieved the isolation of millions, clogged roads and streets, exfoliated cities, poisoned their air. Television educated and entertained generations of viewers while reducing large numbers of them to stupefaction. Air travel, computers, smartphones, social media—you can say the same for them all.

Winter Vigil doesn’t say it by arguing. Mostly, Kogan makes the case for the times he grew up in by describing their rich texture and leaving us to compare them with being young today.Model airplanes, for example:

The history of flight was still news in the late 1940s, and a boy could daydream about World War I aces and Lindbergh in a Curtiss-Jenny, the plane in which he gained his expertise before his transatlantic flight in his silver Ryan monoplane. Hanging on a wall in Marty’s room was a model of the Jenny’s upper wing, the whole assembly still exposed. We sat at a work table covered with X-Acto knives, tubes of glue, drafting pencils, sharpeners, compasses, pins, assorted plastic stencils, a blueprint for the Jenny’s underwing, and a light to illuminate details. We spent afternoons enlarging designs from model airplane magazines and testing gasoline and diesel engines by screwing them onto plywood motor mounts and bolting the rig to any convenient fence that we would find. After we installed the engines in our planes, we took the finished models to an empty lot in the neighborhood or vacant fields heading to the Rockaway shore [in order to fly them].

This was not a particularly unusual activity for an 11- or 12-year-old in the late 1940s, before television, computers, and video and virtual reality games turned childhood into something else. A lot has been said about children once having been more active, more engaged in play and projects of their own invention, more independent, and more often out-of-doors. Kogan makes yet another point: children, or at least some of them, once had an intimation of history—they had historical heroes and a wish to emulate them—that they no longer have. Eleven-year-olds today, to the best of my knowledge, do not build models of 1977 Apple and digital PCs or dream of being Steve Jobs or Bill Gates.

“What’s left of the old forms and structures falls away,” Kogan writes, “and we all turn a little bit more into exiles in our own country, adrift and homeless under the bombardment of the mechanical and impersonal—in schools, homes, literature, everywhere.” The madness of our times, their progressive destruction of all that is natural without and within (the destroyers of the one and the destroyers of the other, oddly enough, belonging to politically opposed camps)—the belief that it is permissible to scorch the earth, foul the seas, change our sex at will, erase the distinctions between men and women, digitize our lives, make babies in laboratories, let robots and computers do our work and thinking, hope to communicate by computer chips implanted in our brains, plan to avoid the extinction of our species by founding colonies in outer space: is it mere nostalgia to think this has something to do with having cut all moorings to the past?

Our politics too. We justly complain that we are led by mediocre types unfit to govern us. But the great politicians of former times went to schools that forced them to study the speeches of Pericles and the campaigns of Alexander the Great—they were educated, that is, to have some conception of what greatness is.

Kogan was wiser than I was. He understood the importance of education at an age at which I was still rebelling against it. In fact, though he took a time-out from it, he never rebelled against it at all. He not only loved high school and college, he even liked grade school. He remembers its “vanished world . . . the awe and authority that radiated from the family to the teacher and the flag in the corner of the room—a lost world of democratic excellence and the natural bonding of community,” about which he says:

My home was admittedly unusual, but #233 was simply a local Brooklyn public school; yet there was Mrs. Levine, teaching neighborhood kids like Lenny Tasch, Bonnie Skellet, and Allan Kaganov to parse sentences, draw detailed maps, and read The New York Times. Nowadays, learning and imagination are described as if they were conflicting worlds, and it seems almost impossible for me to communicate the combination of strict order and unbounded wonder I experienced at school. . . . There we were, in the supposedly narrow-minded ’50s, in an ordinary working-class neighborhood, under an educational system that has been mercilessly attacked by the academic left, and all the time we were being given an elementary school education that many high school and even college graduates today have not received.

Kogan’s gratitude for what schools have taught him is immense. And he knows whereof he speaks in discussing education’s decline, because having returned in the end to graduate school and gotten his PhD, he taught for many years at Manhattan Community College and its Writing Center. Half of his students there, he tells us, didn’t know the geography of their own city, “let alone its place in the larger world,” to say nothing of the place in space and time of other cities, states, and countries. Never having had the “strong and independent teachers” that he had or “the authoritative and deep curriculum” that grade schools, high schools, and colleges once insisted on before they caved in to the demands of cultural relativism and social relevance, such young people are doomed to go about half-blind, unable to see beyond their own immediate experience.

More than about education in our society, however, Winter Vigil is about the education of its author, a Jewish boy born in Brooklyn in 1938 who struggled to put together the confusing pieces of a life: his Eastern European immigrant home; his enticing, enslaving mother with her imagined idyll of the tsar’s ancien régime; his resourceful but ultimately helpless father and the broken dream of the Revolution; the tough streets of Brownsville; his schooling; his overabundance of talent (Kogan passed the entrance exam to Music & Art not in music but in art); his love of literature and painting; his wanderings in America; his need to be silent; his need to speak. On a first reading, I was overwhelmed by the book’smass of detail, the memories, anecdotes, and sketches that crowd its pages like the parts of a Curtiss Jenny scattered on a work table. On a second reading, I began the work of assemblage. On a third, the brilliantly coherent structure of it all, the perfect fit of all the parts, came fully into view.

I knew Kogan was Jewish, of course. His family name was enough to tell me that. But how Jewish he was I had no idea until reading Winter Vigil, even though he and his daughter Sonya had been my family’s overnight guests in Israel in 1982.

To tell the truth, I don’t remember that visit very well. Kogan mentions my taking him and Sonya to the archeological site of Megiddo, so I suppose I must have. The clearest memory I have is of him astounding my own two daughters by spearing a piece of pickled herring on the breakfast table, asking for maple syrup, pouring it over the herring, and chewing the improbable morsel with grunts of satisfaction and a straight face betrayed only by the twinkle in his very large and blue eyes—eyes, as I recall, that seemed to open wide at all they looked at, as if the world were an endlessly interesting and puzzling place.

I can’t state for a fact that Kogan didn’t talk to me during this visit about his childhood, his Yiddish-speaking parents, his father’s years as a halutz in Palestine and knowledge of Hebrew, or his father’s relatives Riva and Solomon who lived in Hadera, a 20-minute drive from our home, and whose old-time Israeli ethos of simple living and pride in their and their country’s accomplishments made a deep impression on him. To the best of my memory, though, I first learned of these things from Winter Vigil.

When I think of it, it wasn’t just Kogan. Today I’m amazed by how many boys I knew in high school and college had Jewish sides I wasn’t aware of until I found out about them long afterward, often inadvertently. I didn’t even realize Lennie Jenkin was a Jew until he married a girl who wasn’t. And when, in middle age, Micky Solomon became a ba’al teshuvah, a newly observant Jew committed to a life of Jewish ritual and study, it was a total surprise for me. I had no idea where it came from. By then, he was the poet Mark Solomon, who had written:

Can you sing in Arizona? Does that train grinding into town,

containers of Pacific mildew–Hanjin, Sealand,

Evergreen–bolted down on flatcars in Seattle, make

your bed jangle in the middle of the night?

And who now wrote:

Words are inscribed on my doorposts and

on my gates, bound for a sign upon my arm, for frontlets between my eyes. Words

that I speak when I’m sitting in my home, when I travel on a journey

to the Land of the Patriarchs.

And who of my friends knew how Jewish I was? I must have surprised them by moving to Israel as much as Micky surprised me.

It wasn’t that we were embarrassed by our Jewishness or went out of our way to hide it. We justdidn’t know what to do with it or where to put it. It had no obvious relation to the Americans we were or wanted to be or to that “all-embracing and positive vision of America,” as Kogan puts it, that “flowed from the spirit of Whitman’s poetry.” Whitman, without whom there would have been no Democratic Vistas, no “Song of the Open Road” (and no Kerouac), no now-preposterous-sounding lines like:

Singing the song of These, my ever-united lands—my body no more inevitably united, part to part, and made out of a thousand diverse contributions one identity, any more than my lands are inevitably united, and made ONE IDENTITY.

That identity was a myth. It came out of the Civil War and out of Whitman. You’ll find it in him even before the Civil War. In one of his typical catalogs of trades and occupations, written on the war’s eve, he lists:

The camp of Georgia wagoners, just after dark—the supper-fires, and the cooking and eating by whites and negroes. . . .

These are the negroes at work, in good health—the ground in all directions is cover’d with pine straw;

In Tennessee and Kentucky, slaves busy in the coalings, at the forge, by the furnace-blaze, or at the corn-shucking,

In Virginia, the planter’s son returning after a long absence, joyfully welcom’d and kiss’d by the aged mulatto nurse.

Today lines like these could get—may already have gotten—Whitman banned from the public libraries. But far from being proslavery, they affirm the single identity of the slave and the slave owner. This was the myth of an America of a sturdy, shared camaraderie beyond all divisions of race and class that Steve Kogan was taught at Public School 133 and that brought me and a girlfriend to Alabama in 1964–1965, a year that started with freedom songs and the Selma marches and ended with the Watts riots and the myth beginning to fall apart.

The filter of forgetfulness! The stray memories that slip through it!

Micky and Kathy Solomon came down from New York that winter to spend a few days with us in Alabama. One evening we decided to drive to a small town an hour away to hear Martin Luther King preach at a local church. We had been in Washington for his “I Have a Dream” speech, but this was a chance to hear him in another setting, a black preacher talking to black people, not to the nation.

At the last minute, Micky announced he wasn’t coming. This wasn’t like the March on Washington, he said. It wouldn’t be right, the four of us sitting at the back of a black church. The church wasn’t ours. We would be voyeurs.

We argued with him. No one would mind if we were there. The black struggle was ours too. The churchgoers would know how we felt.

We went without him and were thankful for the experience because King was in fact different in a country church than he had been at the Lincoln Memorial. It was only gradually that I understood Micky better. And it wasn’t just the church. It was all of it, all of us white Northerners, a high proportion of us Jews, who had come south to be part of something. We were idealistic about what we were doing, but that’s what it was for us: an experience. We had come and we would go, taking the experience with us so that we could reminisce about it someday as I am doing now, while the blacks of Georgia and Alabama and Mississippi would remain. We were Americans and their struggle was ours—but not in the same sense, not in the same way. In that sense and in that way, we were voyeurs. My black students knew it all along. It was in the looks they sometimes gave me, those guarded, curious, almost amused looks that I hadn’t known how to interpret and that had said: Yes, we’re grateful that you care, grateful for your show of solidarity—but don’t think we don’t see through you; don’t think we don’t know why you are here.As the year moved from Selma to Watts, a radicalized black civil rights movement let us know that it knew too, that it would continue without us.

In my relationship to America, as in America itself, that year was a turning point. I didn’t want to be a voyeur. I had my own people, just as black Americans had theirs. The myth of Whitman’s America was falling apart for me, falling apart for us all.

National myths can be dangerous, but they are what make a nation a nation and not just the conglomeration of its citizens that America has since become. It never found anything to replace Whitman with.

Building his cabin, it struck me while reading Kogan’s book for the third time, was his first attempt at writing Winter Vigil. “I go through memories,” he writes, “the way I built my cabin on the hill, finding lost and abandoned things and giving them another home—reading a notice one day in a local paper that I could salvage all the materials I might need by clearing out a basement and helping to tear down an old and unused barn—and then the lugging of windows and lumber, a wood stove, roofing tar, and tin.”

All through the summer of 1968, he tells us in the book’s penultimate paragraph, “I worked on my cabin at the end of the woods, while streams of people from around the country found their way to our communal house. The whole scene was a heavy dose of the ’60s, coming all at once.”

He describes it: the artists, the drifters, the dropouts, the draft resisters on the run to Canada, “one or two professors checking out the scene, an Indian who had wandered east, walking almost all the way from Ohio to Vermont, a precocious high school kid from New York who was looking for the universal language.” Then come the book’s final lines:

December 14, 1968—midnight on the frozen hills. In the main house, nearly everyone is gone. I sit inside my cabin like a winter animal or dormant seed—a kerosene lamp and a candle by the window—a stick of incense glowing in the dark. Smoke blows faintly in the icy air—a copy of Walden, The Magus, and Raja Yoga on my desk—the yoga of the mind—things and images in proper place—my cabin-mother keeps me warm. I watch over my thirtieth birthday as my old life slips away.

My cabin-mother! A whole summer of work, an eager torso bared to the sun, “the preparatory jointing, squaring, sawing, mortising, / the hoist-up of beams, the push of them in their places, laying them regular, / setting the studs by their tenons in the mortise according as they were prepared,” the pausing to brush the sweat from one’s eyes, and stepping back to take a look at what has been done and what remains to be done, and again back to work—and to what end?

To build a cabin-mother, a “sacred icon in the woods—the hermit monk’s retreat and woodland monastery cell” (that’s Kogan, not Whitman), a wintry womb of silence with its “unconscious desire to relive the snow scenes in my Russian book of fairytales and melt the frozen mother-feelings of my heart.”

Unconscious desire. Kogan wrote these words years later. That summer in Vermont, he thought he was just building a cabin. He didn’t realize it was a womb to retreat to and be reborn from.

The cabin was his dream. Winter Vigil is its interpretation. But the interpretation is modeled on the dream. Kogan’s book is constructed from every scrap of memory, every “lost and abandoned thing” from his first 30 years that he was able to find a use for.

A piece of junk ceases to be junk when it is assigned a functional purpose. A stray memory ceases to be stray in the same way.

Winter Vigil, according to Carol Rusoff, didn’t consciously start out as an integrated whole. Kogan began it, she has written to me, in his cabin that winter. When he left the cabin and returned to New York, “he started thinking about his past in earnest. . . . He had a manila folder labeled Sketches,and he threw whatever he wrote, unedited, in there. There was no order to them during those years.” Only in about 2010, Rusoff recalls, did he begin to think of these sketches as the chapters of a unified volume. This was four years before being diagnosed with cancer, after which, she wrote, “He worked on them continually until he couldn’t sit up any more. Then he died.”

And yet a more integrated whole than Winter Vigil could hardly be imagined. The book is a wondrous demonstration of how everything, as Kogan writes, “exists in everything, as we are microcosms that incorporate the world.” One can open it at random to almost any page and see the truth of this.

Here, I’ve done just that:

There is a landscape painting by Jacob Ruisdael that shows a Dutch field stretching out to an infinite horizon, in which the point of view is taken from the rise of a hill, so that one is looking out and down upon a great expanse, with massive clouds moving straight across the sky. There is a late afternoon stillness over the scene, as though it were late afternoon in the universe, in which a solitary figure draws us into that exquisite drama of the infinite. . . . No one ever painted a landscape like that before the Dutch. . . . When Columbus found a continent beyond the horizon by pursuing an idea, he was doing what the Dutch did. . . . They too showed Europe new worlds inside of old.

I read this passage that my finger has blindly fallen on and marvel. Kogan’s deep knowledge of art and the Old Masters—the stillness of the scene, like the stillness with which his mother filled their Brownsville apartment—the hilltop view “looking out and down upon a great expanse,” as Winter Vigil looks back upon a life—the “late afternoon of the universe” (it is late afternoon in his life as Kogan writes)—the solitary figure drawing the viewer into an “exquisite drama,” an “endless distance” (the mother again!)—the new world of America, the idea of America (Whitman!): all in a brief description of a 17th-century landscape. Was Kogan aware of all this as he wrote? I doubt it. “The unconscious never fails to astonish me,” he says:

If I planned a piece of writing from beginning to end, I could never organize it as precisely as free association allows me to do, for I would be imposing an order instead of allowing the material to come up as though by itself, in all its surprising and truly connected detail.

Lumber from here, windows from there, a wood-burning stove from somewhere else, and at summer’s end—a cabin!

Whose womb he enters to “melt the frozen mother-feelings” of his heart and from which he emerges to write about them, his silence ended like Cordelia’s at the end of Lear.

With this melting comes an outpouring of love. For his mother, her witchlike spell cast off at last, now seen by him as the beautiful, haunted soul that she was, a fairy princess transformed into a Baba Yaga by her obsessive need to preserve and control. For his father, whose vital spirits were crushed by the burden of an ill wife and the terrible failure of a faith. For the vanished New York and America that he grew up in. For his teachers and friends. For the past, the smallest remembered detail of which he chronicles as though it were something precious.

Which it is if you can find a use for it.

The year I was a student in England, I had a tutor, a poet and a mystic, who once said, “You know, you spend the first part of your life working your way into your incarnation and the last part working your way out of it.”

I didn’t know what she was talking about. How could I? I was still working my way in. Today, I think I get it. I would just phrase it differently. I would say you live a life that’s messy with experience and clean up by leaving something complete. You don’t do that by throwing anything away. You do it by putting everything in its place.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Upon Such Sacrifices: King Lear and the Binding of Isaac

How Shakespeare helps us think about the akedah, and vice versa.

Lives in Translation

The elegant essays in Hillel Halkin's new book are the fruit of a lifetime devoted to Hebrew literature.

Rethinking Jabotinsky: A Talk with Hillel Halkin

The Jewish Review of Books and Yale University Press hosted an evening for Hillel Halkin’s brilliant new biography of Vladimir Jabotinsky at YIVO.

Wisdom and Wars

If it were fiction, Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom would be the greatest English war novel.

Rabbi Herbert Yoskowitz

Ah , Memories! I appreciate quality reminiscences of writers such as Hillel Halkin Notably missing from this book chapter were tears . Yes , tears . At times ,I , too , have been tempted to romanticize my early years and I have . At the same time , I remember the tears of Professor Abe Halkin who in a Rabbinical School history class at The Jewish Theological Seminary of America dismissed our class early because he began to cry as he read a Hebrew rendition of a medieval pogram. Going back in time , I remember being dazed as a 7 years old Etz Chayim Yeshiva student while attending a school -wide assembly at which faculty cried openly during a broadcast from Israel . These were survivors of the SHOAH , a subject which I now teach at a medical school .This JRB article is good but reflection on what in his past brought him to tears would have improved this chapter

Robert Rockaway

Reading this essay brought back my own memories of growing up in Detroit, of graduate school at Michigan, and of moving to Israel in 1971, at the ripe old age of 32. It also brought back memories of good friends I no longer see because they remained in the United States while I married and lived in Israel. It reminded me of how our lives have taken different paths since then. My army reserve service, which none of them ever experienced, and of all their worried phone calls to me during the 1982 Lebanon War to see if I was okay. I have read other writings by Hillel Halkin and all of them have moved me.

maieutic

Elegant equipoise of head and heart.

What a lovely and loving essay!