Fog

The fog that surrounds me all year grows heavier in the month of Tevet. By Pesach, I can no longer see. It dissipates some after Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s Memorial Day, but a cloud remains. Only my wife, Ilana, understands my half-blind groping. For she, too, lives in the fog.

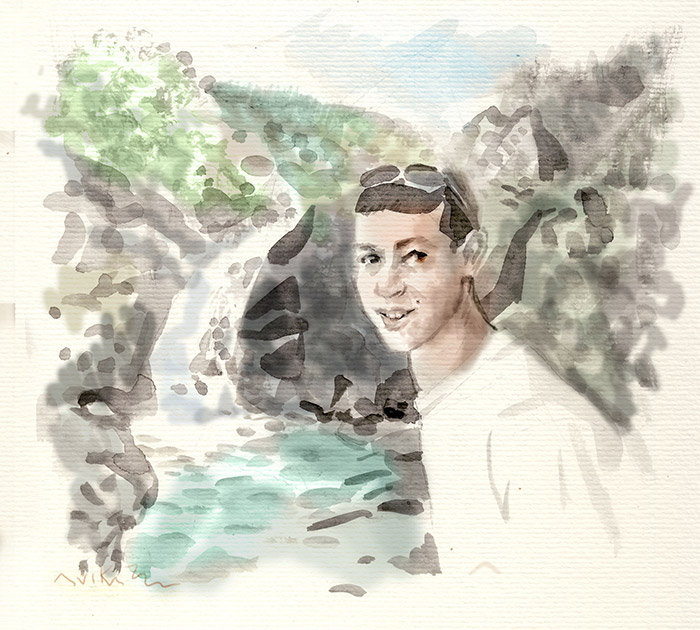

The ninth day of Tevet this year would have been Niot’s 30th birthday. We lost him when he was 20; our last night with him was the Seder. The fog descended three days later, on Friday morning, a day after his diving accident in Eilat, when the doctors at the hospital told us that we had lost him. On Shabbat, his death was officially certified, and we signed the documents to allow his organs to be donated. His funeral took place on Sunday, early afternoon, the eve of the last day of the holiday. When he died, he was a soldier, so two weeks later we found ourselves again at the military cemetery on Mount Herzl, marking our first Yom HaZikaron as bereaved parents. Since then, these dates, his birthday in Tevet and Yom HaZikaron in Iyar, bracket our season of mourning, the time when we can barely see anything at all.

One Shabbat afternoon, during the sunless summer that followed Niot’s death, I walked to a park in our South Jerusalem neighborhood. The trees were charcoal lines, fading at the edges into a dull sky; wraiths walked, ran, and cycled by me; and voices sounded as if through a thick wall. One came louder than the others and repeated itself, twice, then three times, and finally, I turned toward the sound. A long moment later, I made out the face of a friend, sitting on the grass with his infant daughter. I stepped toward him, and he said some words; I offered some in return. He spoke again, but the words were as if suspended in the haze between us, unable to reach me.

“How could he not see the fog?” I asked Ilana when I got home.

We have learned to live with it. We allow more time for the simplest of interactions, time to get our bearings, to identify the blurs and the muffled vibrations. We stay closer to familiar routes and people. We’ve even learned new ways to focus.

Once, when Niot was in his early teens, we were at the end of a long drive after a Pesach family vacation in Eilat. The kids were antsy, and my parents, who were visiting from the States, were tired. When we reached Beit Shemesh, I decided to make the last leg more interesting by heading off the main highway and taking a narrow, neglected road that heads up from Eshtaol and follows a mountain ridge to Tzuba, just west of Jerusalem, with stunning views. Just past Kisalon, we drove into a fog that came out of nowhere.

At first, the view from the road, which runs along the edge of a precipice, was blocked. Soon I could barely see a meter in front of me. I slowed the car to less than a walking pace, tensely watching the asphalt, looking for the faint light cast back at me by road signs and for the nebulous headlights of the cars coming toward us. Had I let my concentration down a moment, we would have been lost, and turning back or stopping would have been even more dangerous.

This is what the season of mourning for Niot is like every year. The fog requires the mind and the body to rally all resources to the task of getting where they must go. This explains why, to outside observers, we seem to be doing so well. And, by any empirical test, we are. Ilana and I work and love and play and exercise and spend time with family and friends and are active in our community and with the educational project we set up in Niot’s memory. But if we were to let up for a moment, we would fall into the depths below.

Four decades ago, I visited my family in Washington, DC. I had just made the decision to make my life in Israel and had come back to make arrangements. One foggy evening, I drove to visit an old friend who had moved to a distant suburb I had never been to before. She had given me long, involved directions over the phone, which I’d scribbled down on a piece of paper torn from a small notepad, as one did in those days. The fog, blocking the light of the sun, caused night to fall with unexpected abruptness, and I couldn’t read the directions at my side as I drove. I felt as if I were floating alone in the universe with no way of getting my bearings. Each time I reached a landmark or made one of the turns my friend had described, I slid over and stopped on the shoulder to check the piece of paper for what I should be looking out for next, the signpost that would emerge from the murk only when I had almost passed it.

After one of the many turns, I pulled the car over and turned on the overhead light to look at the directions. “Just after the train crossing,” I read. Not a sound, really, but the impression of a sound, a sort of low whistle, reached me from a distance. I looked up but couldn’t make out where I was. What I could see was a faint and strange pulsation of red in the fog before me. A vague impression of a fuzzy spot of light, like a distant galaxy, appeared on my right. Then, just as the whistle sounded again, still muffled but louder, its pitch rising, I glanced in the rearview mirror and saw a red pulse behind me as well. And I realized that I had stopped on the tracks and that a train was coming straight at me. I stomped on the gas pedal, but the car only made noise until I finally threw it into gear and zoomed off the tracks just in time.

The train hit me—hit us—31 years later. I didn’t die. I learned to live hurtling head over heels in the void. If I gaze intently, I can usually see the next signpost and make the correct turn. If I listen closely, I can generally make out conversations. I feel Ilana’s hand in mine, and we navigate through a fog that no one else sees.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Businesswomen Before Bar Kokhba

Why did a Jewish woman living 30 years (around 135 C.E.) after a set of real estate contracts were executed and with no obvious connection to the named parties have them in her satchel when she fled Ein Gedi?

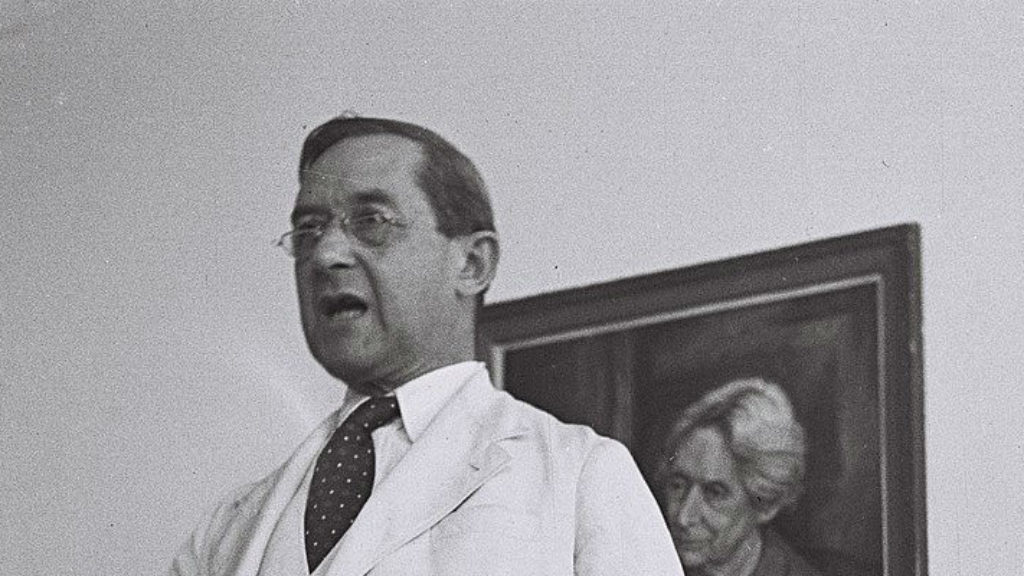

A Good Second Choice

Yirimiyahu be-Tzion is a solid work of intellectual history, devoted above all to understanding Judah Magnes as he understood himself, sympathetic but honest, and attentive to the weaknesses as well as the strengths of his thinking.

Fauda: The Wages of Chaos

Fauda, which takes its name from the Arabic word for chaos, opens in an adrenaline rush of noise, confusion, and jagged camerawork.

A Normal Israel?

Zionism has long based its claim to sovereignty on the universal right to national self-determination, and the phrase “like all other nations” has been incorporated into Israel’s Declaration of Independence, yet the goal of “normalization” has proven to be much more complicated than most early Zionists had thought.

Anne H Berman

This was very moving. Thank you so much for sharing it.