Businesswomen Before Bar Kokhba

Sometime toward the end of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 C.E.), a Jewish woman named Babatha, daughter of Shimon, fled Ein Gedi with a group of fellow Jews. She had been visiting her stepdaughter and ended up in a remote cave in the Judean desert, accessible only by a narrow ledge carved into sheer cliffs 650 feet above the canyon floor. Like fleeing refugees of other times and places, Babatha carried her most important papers with her, so that she would be able to reclaim her property and re-establish her life when the war was over. However, she and the Jews she was hiding with either died of starvation when Roman soldiers cut off their supply lines or were killed outright when the soldiers penetrated the refuge. Sometime before that happened, she hid her satchel with its 35 documents, including wedding contracts, a property registration, legal petitions and summonses, deeds, and loan notes, in a recess of the cave. These documents were written between 94 C.E. and 132 C.E. in Nabatean Aramaic, Judean Aramaic, and Greek. More than 1,800 years later, in 1961, a research team led by the Israeli general turned archeologist Yigael Yadin discovered Babatha’s archive when a rock wobbled under the feet of a volunteer, revealing the satchel. They also found several other items that likely belonged to Babatha, including a pair of sandals, balls of yarn, two kerchiefs, a key and two key rings, bowls, a clasp knife, and three waterskins.

Yadin’s more famous find in the “Cave of Letters” was the correspondence between Bar Kokhba and his generals Yehonathan and Masabala. What Philip F. Esler demonstrates in Babatha’s Orchard: The Yadin Papyri and an Ancient Jewish Family Tale Retold, an ingenious and meticulous work of reconstruction, is that the documents in Babatha’s satchel shed light on the everyday lives and business practices of Jews and Nabateans who were caught up in the conflict. In contrast to most surviving ancient literature (which was written by and for men), these documents feature women prominently, wheeling and dealing, acting as sellers, buyers, lenders, litigants, and trustees.

Esler’s book focuses on the earliest four documents of Babatha’s archive, all written in Nabatean Aramaic with execution dates ranging from 94 C.E. to 99 C.E., before Babatha was born. One of them records the sale of a date palm orchard to Babatha’s father Shimon in 99 C.E. It is easy to see why Babatha would have held on to this document, since her father had apparently given her the orchard (she registered it as her own in a Roman property census in 127 C.E.). But the other three papyri record transactions among Nabateans who have no apparent relationship to Shimon or Babatha. The question at the center of Esler’s clever microhistory is, simply, why? Why did a Jewish woman living 30 years after these contracts were executed and with no obvious connection to the named parties have them in the first place? And why did she consider them important enough to carry into hiding?

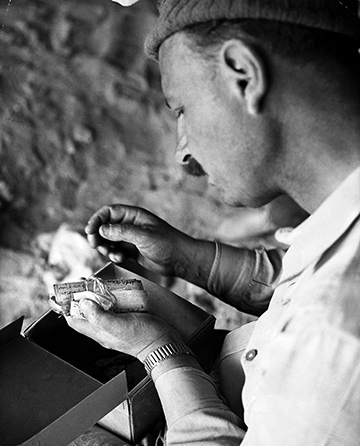

To tell the story of these four documents, Esler must reconstruct their purposes, their parties, their provisions, and much more. At points, the papyri themselves are so damaged that all that remains of a word is a faint trace of, say, the upper stroke of a lamed. Esler does the hard paleographic work of reconstructing missing letters by comparing the vestiges of damaged letters with clearer samples from other documents by the same scribe, often showing photographs so readers can judge for themselves. And, of course, like all good scholars of antiquity, Esler knows how to read texts closely and how to set them in their historical and cultural contexts (one learns a lot about the Nabateans along the way). But Esler also has a trick up his sleeve. Before becoming a Bible professor, he was an attorney, and he leverages that professional experience to great effect. Esler knows that behind every contract stands a lawyer. The scribes who wrote these documents not only committed words to papyrus, they carefully framed the terms that would mitigate each party’s risks in the transaction.

The property that Shimon bought in 99 C.E. was a date palm orchard located in Maoza, a harbor town on the southern shore of the Dead Sea on the Nabatean side of the border with Judea. The seller was a Nabatean woman named ’Abi-‘adan, and the deed lays out the boundaries of the property, establishes the new owner’s irrigation rights, and sets a price. It is signed by the seller, her guarantor, four witnesses, and the scribe. As per Nabatean legal custom, as purchaser, Shimon did not sign; the sale went through when he received the signed copy as proof of ownership.

Curiously, one of the other four documents is another deed of sale for the same orchard (with slightly different boundaries) dated just one month earlier. It is written by the same scribe, but this time ’Abi-‘adan is selling her orchard to a highly placed Nabatean official, Archelaus, son of ‘Abad-‘Amanu. Until now, scholars assumed that the sale to Archelaus was simply never finalized, leaving Shimon free to buy the property one month later. Esler, however, finds traces of a witness’s signature, which would mean that the sale did go through.

What happened? Whatever it was, Shimon would have wanted assurances that ’Abi-‘adan had regained clear title to the property before she resold it to him. Esler speculates that Shimon demanded possession of the signed, but now overridden, deed of sale, and Archelaus apparently agreed. This document was important to Shimon (and later Babatha) because it meant that neither Archelaus nor his heirs could produce it and claim that the orchard was theirs.

As Esler shows, Shimon took additional measures to protect himself from later claims by Archelaus. He observes that a man named Archelaus appears as the first witness on the deed of sale to Shimon. Earlier scholars have simply assumed that this witness Archelaus was not the same as the Archelaus who purchased ’Abi-‘adan’s property one month earlier, but Esler disagrees, since it turns out that the Greek name was particularly unusual for a Nabatean. Having Archelaus witness Shimon’s purchase was apparently another device to secure Shimon’s title. Archelaus (and his heirs) would have trouble contesting the validity of a purchase for which he himself had served as a witness.

But if the sale to Archelaus really did go through, how and why was ’Abi-‘adan selling the property again one month later? Esler speculates that shortly after purchasing the property Archelaus found himself in a sudden cash crunch, leaving him no choice but to approach ’Abi-‘adan and request that the sale be rescinded. An obscure detail in the earliest of the four documents, which other scholars have barely remarked upon, strengthens Esler’s conjecture.

The earliest document of Babatha’s archive is a deed of debt executed in 94 C.E., five years before Shimon bought ’Abi-‘adan’s orchard. It records a large loan from a Nabatean woman named ’Amat-’Isi to her husband, Muqimu, drawing upon her dowry. The loan is granted interest-free for two years, at which point “customary” interest rates apply (20 years later in Nabatea the standard rate was 9 percent). A third party, ‘Abad-‘Amanu, serves as guarantor in the event that Muqimu fails to repay the loan. Esler reasons that Muqimu and ‘Abad-‘Amanu were borrowing money to finance a joint agricultural business venture. If things went well, the loan could be repaid from the profits during the initial term of two years. If not, the terms of the loan authorized Muqimu and his partner to borrow an additional large sum from ’Amat-’Isi’s dowry, again interest-free for two years. But there was a catch: ’Amat-’Isi could call in the debt at any point after the first two years.

Is it mere coincidence that Muqimu’s guarantor and partner ‘Abad-‘Amanu has the same name as Archelaus’s father? It hardly seems likely, otherwise why would the document have any importance to Babatha? Now suppose, Esler suggests, that Archelaus’s father ‘Abad-‘Amanu died just when ’Amat-’Isi called in the debt on her husband and his partner. Archelaus would have suddenly needed to get his hands on a large sum of cash—and fast. So he sold the orchard back to ’Abi-‘adan, who sold it to Shimon, who gave it to his daughter Babatha, which is why she carried these documents with her as she was fleeing the Romans.

At points, the reader may feel pressed to cede Esler so many conjectures. For example, did Shimon really make Archelaus, son of ‘Abad-‘Amanu, whose sale was rescinded one month earlier, serve as witness for his own sale? It makes good business and legal sense, but we cannot know for sure since Archelaus’s signature on Shimon’s deed is damaged. All that remains is “Archelaus, son of —.” The catch is that the illegible father’s name is just three letters long, which means that ‘Abad-‘Amanu does not fit in the available space. This forces Esler to hypothesize that Archelaus signedusing a three-letter word that was his father’s old nickname from the military. This may be plausible, but it is very far from certain. After all, there is no evidence that ‘Abad-‘Amanu used a nickname or even served in the military! Such qualms notwithstanding, the story Esler tells is compelling, if speculative at points.

It must have been difficult for ’Amat-’Isi to watch her husband’s business fail, knowing that her dowry, which would be her lifeline if her husband were to die or divorce her, was slipping away too. So she called in the debt. (As other documents show, Babatha found herself vulnerable in exactly this way.)

In short, it was the bold personal and business decision of one Nabatean woman, ’Amat-’Isi, that forced the Nabatean official Archelaus to request another enterprising Nabatean woman, ’Abi-‘adan, to allow him to rescind his purchase of her orchard, which she did, presumably because she had another buyer waiting in the wings, namely Shimon. And it was Shimon who bequeathed the orchard, together with its complex documentary history, to his enterprising daughter Babatha.

Esler’s book has the twists and turns of a detective story, but its biggest surprise is the people into whose world we have been permitted to peer. Women, at least the upper-middle-class Jewish and Nabatean women of Babatha’s circle, turn out to have been major financial players in this world. They bought and sold property, financed ventures from which they stood to gain, and even protected their interests at the risk of legal and marital conflict when things did not go according to plan. Babatha’s resourceful foresight, together with Philip Esler’s lawyerly scholarship, have granted us a glimpse into a fascinating social world that defies our preconceptions and calls out for further study.

Suggested Reading

It Is Either Serious or It Isn’t

A poem by Chana Bloch is like a stone thrown deep into the well of experience.

Ink and Blood

Arthur Szyk may well be the only great Jewish artist whose work countless people recognize simply because they have attended a Passover Seder. Less well known are the explicit connections between the Egyptian pharaoh and Hitler that Szyk had embedded in his original version of the haggadah he created in the 1930s.

No Greater Love

The Israeli music scene is bringing together world-class Israeli jazz and classic Sephardic liturgical music. Voilà!: the jazz piyyut.

Athens or Sparta?

A new "inside story" of the Israeli military reveals more about the current prejudices of the chattering classes than it does about Israel and its neighbors.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In