Let the People of Israel Remember

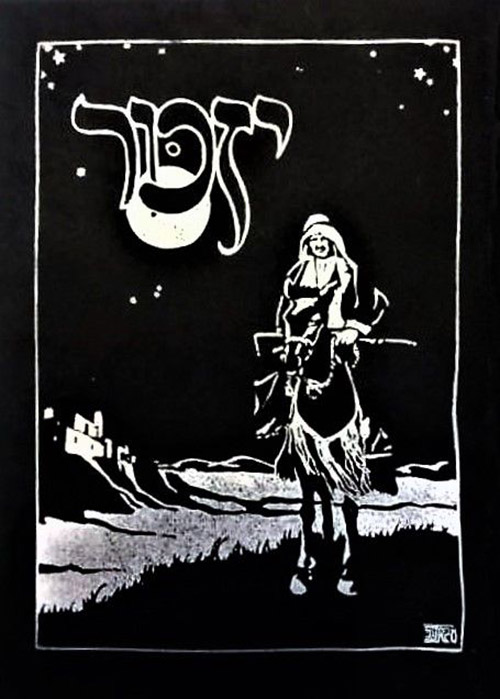

The earliest literary commemoration of Zionism’s fallen heroes was a book entitled Yizkor, published in Palestine in 1911 by members of Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion). The men it honored hadn’t fallen in battle but had all been ambushed while on guard duty, with no witnesses around. Their deaths, as Anita Shapira puts it in her Land and Power: The Zionist Resort to Force, 1881–1948, were “hardly the stuff of which tales of valor are made.” But they were sacrifices nevertheless, and their comrades chose to remember them in a quasi-religious way. The Yizkor book echoes the traditional memorial prayer, but it doesn’t repeat it. Instead of calling on God, it begins, “Let the people of Israel remember.” As Shapira writes, “This is a collective memorial service of the people, and the people is supposed to derive conclusions from the death of its heroes and apply them to its new life.”

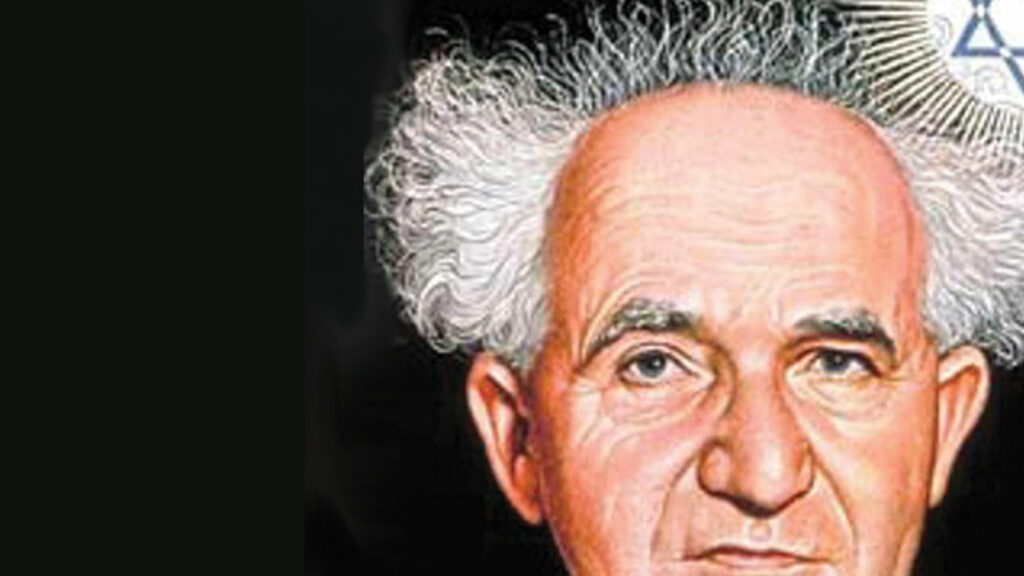

While Yizkor doesn’t seem to have had a significant impact in the Yishuv, a couple of rank and file members of Poalei Zion found it very useful a few years later. Expelled by the Turks from Palestine at the beginning of World War I, David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi had made their way to the United States, where they were struggling to put their party on the map. With this aim in mind, they initiated in 1915 the publication of a Yiddish translation (for who in America could understand Hebrew?) of Yizkor. As Tom Segev writes in his recent biography of Ben-Gurion, it was “a huge success. Memorial evenings were held all across America, and Ben-Gurion became a sought-after guest.”

When copies of the first edition ran out, Ben-Gurion published a second, revised version. He tossed out what he thought was an excessively polemical and poetical introduction and wrote a new one, in which, according to Segev, “The heroes he memorialized came out looking like gods: ‘They came not as beggars but as conquerors,’ Ben-Gurion began. That was followed by a period and then: ‘In the beginning was the deed.’… The message was nationalist and secular and related to the dead heroes themselves. They had created a ‘religion of labor’ and shed their blood in defense of the land.”

Getting your hands on a copy of Yizkor in Hebrew or Yiddish is hard; I’ve never seen one. But the German version, published in 1918, is almost absurdly accessible. Just go to Internetarchive.org, punch Jiskor into the search space, and you’ll immediately see on the far right of the top line directions to the text of Jiskor: ein Buch des Gedenkens an gefallene Wächter und Arbeiter in Lande Israel put out by . . . Martin Buber. Martin Buber!? What’s he doing here? Wasn’t he one of the most pacifist of Zionists? During World War I, Buber’s friend Gustav Landauer had called him “Kriegsbuber” (war-Buber), but that was on account of his ardent support of the German war effort, not any militant Zionism. And, in any case, by 1917–1918, when Buber produced his edition of Yizkor, he saw things very differently (thanks, in part, to his friend Landauer).

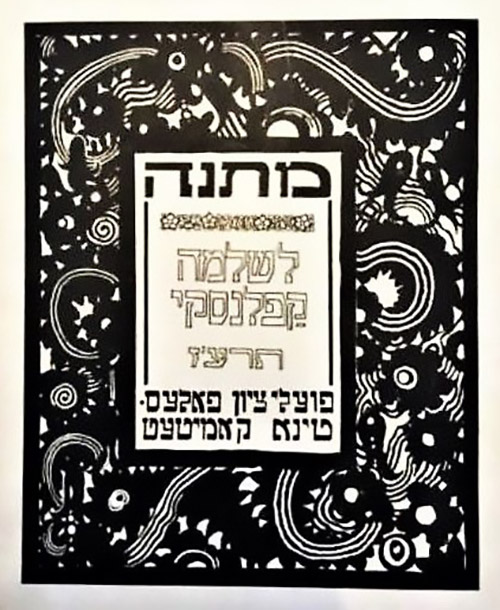

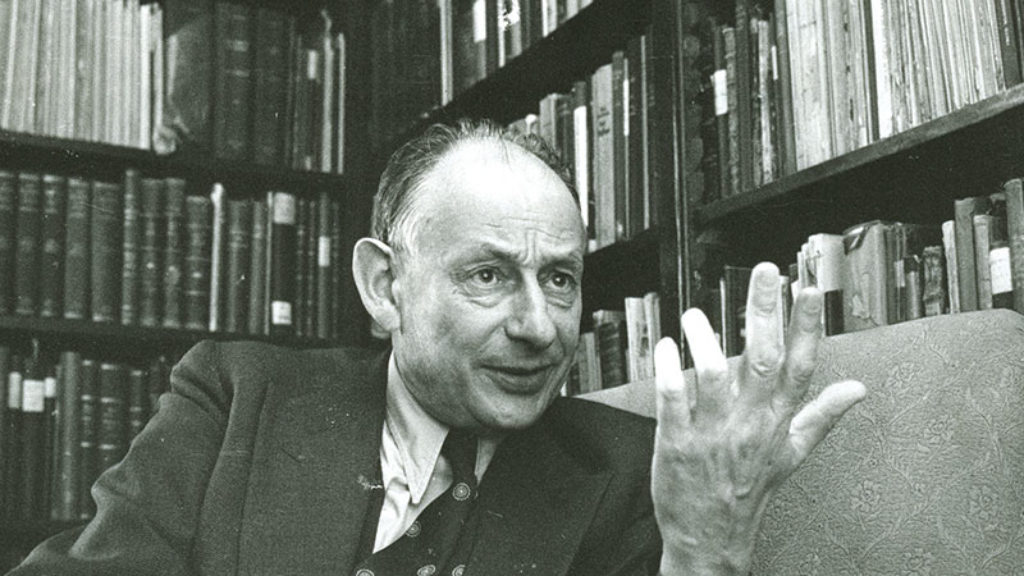

We know something about Buber’s involvement in this edition of Yizkor from the autobiography of the translator, the then-twenty-year-old Gershom Scholem. Having been thrown out of his father’s house in Berlin early in 1917 for his disloyalty to Germany, Scholem was living in a pension together with a very select crowd of Eastern European Jewish refugees, including Zalman Rubashov, a member of Poalei Zion who was ultimately to become the third president of the State of Israel, after changing his name to Zalman Shazar. Knowing that Scholem needed extra cash, Rubashov, who was working with Buber, had asked his young friend to translate Ben-Gurion’s second edition of Yizkor. Scholem modestly protested that he didn’t really know Yiddish. Nonsense, said Shazar. You’ve got Hebrew, and, needless to say, German, and I know you studied Middle High German. The only thing you don’t know is the Slavic words, and for that, you’ve got me.

Scholem was ready to take on the job, but as he proceeded through the work, he found he had rather serious qualms. Some of the militaristic language rubbed him the wrong way, and he told Buber that he didn’t want his name to appear on it (nor, for that matter, did Buber wish to be mistaken for the translator, so they just stuck in some fake initials). There was another problem, too. When he heard about the project, Victor Jacobson, one of the five members of the Zionist Executive, came to Buber and insisted that it had to be abandoned. While a Yiddish version was harmless since it was too inconspicuous to create problems with the Turkish rulers of Palestine, a German version surely would do so. And besides that, the book was, as Scholem had already said, just too bloodthirsty. Buber listened—but waved Jacobson off. And the Turks, of course, were no longer a factor when the translation appeared in 1918. The Balfour Declaration had been issued, and the British had chased them out of Palestine.

Many decades later, on Ben-Gurion’s eighty-fifth birthday, Scholem, who had become the world’s most famous scholar of Jewish mysticism, surprised him by telling him that he had been his first German translator. And now, strangely enough, it is his German edition that is ready at hand, while the ones in the two Jewish languages can be found, to the best of my knowledge, only in rare book collections. It’s an odd fate for a book that marked the beginning of what has become an all-too-rich tradition of commemorations of those who have fallen in defense of Zion.

Suggested Reading

The Secret Metaphysician

While a new crop of biographies about Gershom Scholem all, in one way or another, seek to account for the great man's fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure.

State or Substate?

“Nonstatist” Zionists, as the historian David Myers has dubbed them, have received a lot of attention in recent years. Dmitry Shumsky, a historian at the Hebrew University, is grateful for this scholarship but believes that it has not gone far enough.

Indispensable Man

In his effort to cut David Ben-Gurion down to size, Tom Segev blames him for failures that were not his and gives him insufficient credit for his achievements. A closer examination of the historical record reveals a greater man than the one Segev attempts to dissect.

Zionism’s Forgotten Father

Nathan Birnbaum, one of Zionism's early leaders, looked like Herzl and wrote like Herzl (albeit not as successfully). But his unusual trajectory has reduced the space that might have been assigned to him in the history of Zionism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In