The Secret Metaphysician

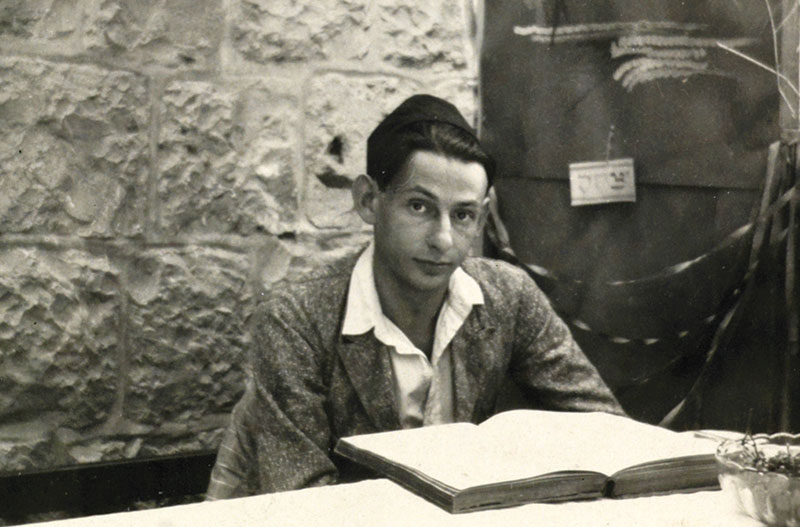

I never met Gershom Scholem, though I could—or better still, should—have. In 1978, working on my doctorate on the encounter between Eastern European and Western European Jews, my advisor George Mosse told me that I absolutely had to interview the Master. In 1917, after being banished by his father from the family home for his opposition to the war and excessive Judaism, Scholem had lived for a while in a Berlin boarding house called Pension Struck, where he befriended leading Eastern European Jewish intellectuals, including the great Hebrew writer S. Y. Agnon, who would become his lifelong friend, and Zalman Rubashov (later Shazar), future president of Israel. He was, in fact, a living witness and participant of the cultural story I proposed to tell. But at that stage of my life, telling me to approach Scholem was akin to saying, “Why don’t you visit God?”

I stood in awe of the man whose writings flashed off the page like the holy sparks he had identified in the Kabbalah. Scholem managed to mesh the holy with the subversive, creation with destruction. He had animated a seemingly moribund tradition with messianic notions of the apocalyptic, the mythic, and the irrational, and his rereading of Judaism was informed by modernist categories—abyss, rupture, paradox, dialectic—that appealed to someone like me, who ordinarily would not have taken the slightest interest in Kabbalah. Moreover, I was aware that he was admired and feared throughout the world, in dialogue (and conflict) with the leading Western thinkers of the time. So, duty-bound but incredibly reluctant, I gingerly set about approaching him in the hope that—like the Ein Sof of the Kabbalah—he would be inaccessible. I looked in the Jerusalem telephone book (today an archaic relic) hoping that the Scholems would not be listed. Sadly, they were. Trembling, I dialed the number in the fervent desire that no one would answer (at that time one couldn’t leave a message) or that Scholem’s second wife, Fania, would come to the phone and tell me that her husband was not available. None of this happened. Instead, after one ring (or perhaps in the middle of it), a loud voice boomed out: “SCHOLEM.” In shock at hearing the great man himself, I immediately slammed the receiver down in terror, never to meet the antinomian maggid (as the Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno called him).

His aura, it seems, was always there. From his tempestuous youth onward, Scholem’s unique and forceful personality was the constant object of both fear and a sometimes-bemused fascination. As early as 1921, Franz Rosenzweig perceptively said of Scholem that he had “not yet found such a thing among West European Jews. He [Scholem] is perhaps the only one who has really already come home. But he has come home alone.” The fascination with Scholem has clearly persisted; indeed, it has grown since his death in 1982. How else can we account for the remarkable fact that—in addition to Princeton University Press’s recent republication of his magisterial 1957 biography of Shabbtai Zevi and the appearance of his 1939–1940 Hebrew lectures on the history of the Sabbatean movement—David Biale, Amir Engel, George Prochnik, and Noam Zadoff have all recently published biographies of Scholem? In addition, Mirjam Zadoff has written a much-needed biography of his ill-fated communist brother, Werner, who was murdered by the Nazis in Buchenwald in July 1940. Moreover, in a forthcoming book, Jay Geller will explore the history and fate of the entire Scholem family as a microcosm of bourgeois German Jewry.

While the biographies in question all in one way or another seek to account for this fascination, they are themselves evidence of Scholem’s ongoing allure. This is only one of the many tasks—and traps—Scholem’s biographers face. The challenge is especially daunting because, in certain deliberate and mischievous ways, Scholem reveled in enigmatic personal and intellectual concealment. He approved of a description of his method as that of “a secret metaphysician . . . disguised as an exact scientist.” At times he referred to himself—in the third person!—as a “master magician,” and when asked if his mystical “quarry may have been all the time in the pursuer,” he responded, “I have invented at least twenty different answers, whereas the true one is hidden away between some of my lines.”

The “ultimate” biographer of Scholem would not only have to document, contextualize, and assess Scholem’s life and scholarship, as well as analyze the relation (or possibly the nonrelation) between the two, but also master key aspects of 19th– and 20th-century German and European cultural and intellectual life, as well as the study of Kabbalah, German Jewry, Zionism, and Israel. That it is possible to even attempt a true biography at all is a result of the fact that we now have his archive, which includes not only his correspondence from 1914 through the end of his life but also his revelatory (mainly, but not exclusively, youthful) diaries. I doubt that we will ever have an ultimate biography. But each of the books discussed here throws new light on a towering and peculiarly unique 20th-century intellectual.

Born into an acculturated Berlin middle-class family, with his restless, brilliant mind and his stormy (indeed, fanatical) temperament, Gerhard (as he was then called) very early on not only rebelled against his assimilated Jewish bourgeois home but also rejected the possibility of any meaningful life for Jews in Germany. As an adolescent, he went in search of a radically renewed Jewish authenticity. Indeed, there are manic moments in his diaries when he seemed to regard himself as the messiah of such a renewal. In a startling passage quoted by Biale, Scholem wrote that Martin Buber had prepared the way for Jewish renewal but was not himself the redeemer:

And the dreamer whose name also signifies that he is the Expected One [is] Scholem, the Perfect One [a wordplay on Scholem and shalem, “perfect,” “whole”]. It is he who must . . . forge the weapons of knowledge.

After a brief flirtation with Orthodox Judaism, Scholem turned to an arcane theo-metaphysical version of Zionism and Hebrew as both the only proper Jewish way forward and “preparation for the eternal.” All the while, he was preparing himself furiously with the linguistic and textual “weapons of knowledge.” In November 1916, he wrote to a friend: “I am occupying myself always and at all times with Zion: in my work and my thoughts and my walks and also, when I dream. . . . All in all, I find myself in an advanced stage of Zionization, a Zionization of the innermost kind. I measure everything by Zion.”

Like his brother Werner, with whom he had a complex relationship, Scholem opposed World War I. Gerhard’s Zionism, Werner’s socialism, and their shared opposition to the war were too much for their explosive father, Arthur, who regarded all three positions as treacherously un-German and angrily expelled the brothers from their home. (Ironically, despite their fundamental differences, as Biale perceptively suggests, Gershom seems to have inherited his volcanic personality from his father.) Unlike Werner, who increasingly turned to the cause of “world revolution,” Scholem turned away from what he regarded as the “impurities” of Europe. His Jewish revolution, he noted in his diary in January 1915, could “not proceed from the corpses of West European strangers.”

It was in 1915 that Scholem met Walter Benjamin, the greatest intellectual and personal influence of his life. Their playful, passionate exchanges around the esoteric and the subterranean, and Benjamin’s interest in language and translation, sharpened Scholem’s textual sensitivity and moved him away from his earlier enthusiasm for Martin Buber’s romantic notion of Erlebnis, a kind of lived ecstatic experience, as the ineffable essence of mysticism. It was during these late adolescent and early adult years that Scholem studied mathematics and, most crucially, as Biale puts it, “transformed himself from a brilliant autodidact with broad, eclectic interests into a highly disciplined scholar of Kabbalah.” Yet what always distinguished Scholem was his broader animating metaphysical vision, a fascination with the redemptive but subversive tendencies at play in the tradition itself. As he later put it, accompanying his scholarly rationalistic skepticism was an “intuitive affirmation of mystical theses that walked the fine line between religion and nihilism.”

In 1923, Scholem moved to Palestine, a few months after his fiancée, Escha Burchardt, who he soon married. He had planned to teach math, but he quickly obtained a position as head of the Hebrew division in the newly formed National

Library and a little later was appointed as a faculty member of the Institute for Jewish Studies when the Hebrew University was inaugurated in 1925. Continuing his research on Kabbalah, and occasionally penning disillusioned poems and

depressed oracular ruminations about the despiritualized condition of the Zionist project (with its emphasis on power politics and statehood rather than Judaic renewal), he joined Brit Shalom, a small group of intellectuals pressing for the creation of a shared binational Arab-Jewish polity. Given their very small numbers, lack of political talent, the absence of support in the Yishuv, and the reality of Arab hostility, their efforts, however noble in intent, were largely in vain.

Settled in Jerusalem, Scholem pursued his kabbalistic studies with fanatic intensity from the 1930s to the 1950s, producing most of the works for which he became famous. Through his major works of that era—the best known are his 1938 New York lectures delivered at the Jewish Institute of Religion, which became Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism—he made Kabbalah’s intricate interplay with and reworkings of tradition accessible and exciting to modern secular audiences by connecting the universal with the particular.

He proposed a three-stage progression of religion and mysticism both in general and specifically for Jewish Kabbalah. Originally, he speculatively argued, religion began with the immediate experience of God. After that unsustainable experience, in the second stage laws and institutions were established, marking the distance between man and the Divine. In the third stage, mysticism appeared as an attempted return to the immediacy of the experience which law had obscured. Mysticism was thus “new” in that it recognized the abyss between man and God. What rendered Kabbalah or Jewish mysticism unique was that it understood itself to be a tradition of interpretation, and hence necessarily mediated by language. Kabbalah, then, was not about ineffable experience but daring speculative interpretation that inquired into the Divine’s inner workings.

It was probably mind-boggling for his American Jewish audience to learn about ideas such as Isaac Luria’s doctrine of tzimtzum, which taught:

[T]he existence of the universe is made possible by a process of shrinkage in God. God was compelled to make room for the world by, as it were, abandoning a region within Himself, a kind of mystical primordial space in which He withdrew in order to return to it in the act of creation and revelation.

To adapt a favorite metaphor of Scholem’s, his lectures revealed the scandalous winds blowing through the apparently not-so-stuffy house of Judaism.

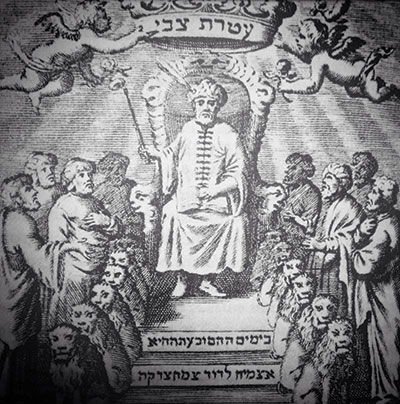

Scholem’s most strikingly subversive essay was his 1937 essay on Sabbatean theology, “Redemption Through Sin.” For Shabbtai Zevi and his followers, some commandments could only be fulfilled through transgression. Thus, Shabbtai Zevi’s conversion to Islam was viewed as part of his messianic task of redeeming the world; the sin of apostasy was necessary to rescue the sparks of good that were lodged in the remotest spheres of evil. In this bizarre theological movement, Scholem daringly suggested, were the seeds of Jewish modernity itself. The breakdown of traditional life was as much an internal, immanent process as it was determined by outside pressures. Paradoxically, the heresy of messianic nihilism had opened the way and prepared Jews for the Haskalah, religious reform, and even the secular Enlightenment.

As David Biale notes, “No reader can ignore the passionate rhetoric in which Scholem tells his story.” The essay is shot through with a profound dialectical ambivalence; his critique of the messianic dangers of Sabbatean and Frankist heresy is unmistakable, as is his obvious fascination, if not relish, for their related forces of liberation and destruction. Rendering these episodes as integral to the Jewish experience was part of Scholem’s insistence that Judaism was an open, living, historical phenomenon, with both utopian and catastrophic potential. Although he wrote in both Hebrew and German in these years, this essay, he felt, could only be composed in Hebrew. Zionism enabled the possibility of history shorn of apologetics, in which one could explore and understand the darker aspects of the Jewish experience.

Scholem could not abide fools. Upon his arrival in Palestine, he recorded his astonishment that he had come across “astoundingly stupid” people. Colleagues and students were often shamed, cruelly intimidated. Yet, his biographers concur, there was also a more gentle, considerate Scholem. His letters to his depressed friend George Lichtheim, the translator into English of Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism who ultimately committed suicide in London, are tender and caring in a fatherly way.

His more vulnerable—albeit inconsistent—side is touchingly revealed in Biale’s unexpected chapter, “Scholem in Love,” which chronicles his early infatuations and makes a strong case that his greatest love was (as his second wife Fania once suggested) Walter Benjamin. Certainly, he shows that Scholem was bewildered by the depth of emotion he felt for his friend. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism was famously dedicated to the memory of Benjamin, who committed suicide when he was threatened with a return to Nazi-occupied France after crossing into Spain: “The friend of a lifetime whose genius united the insight of the Metaphysician, the interpretive power of the Critic and the erudition of the Scholar.”

My late-1970s fear of him notwithstanding, Scholem seems to have mellowed with age. His earlier lack of tolerance was increasingly sublimated into an ironic, impish sense of humor. Prochnik relates the story with which Scholem regaled Cynthia Ozick about a man who was not interested in attending a faraway future social event and who, apologizing, took out his diary and declared, “Oh, I’m so sorry, but I have a funeral on that day.”

More seriously, Scholem’s biographers record the complicated effect that the rise of Nazism and the Shoah had on Scholem. From distant Palestine, he watched events unfold. He admitted that they assumed a somewhat abstract character: “It’s just too far away and nobody has any real notion of what it might be like.” Indeed, his letters to his mother during the early Nazi years, in which he was still requesting that she send ties and marzipan, now make for uncomfortable reading. But there were many palpable, personal shocks: Benjamin’s death, the 1940 murder of his brother, his family’s desperate flight to Australia, and his depressed search through postwar Europe for lost Jewish books and manuscripts for the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction.

Yet, while Scholem famously berated German Jewry for their deluded belief that there ever was or could be “a German-Jewish symbiosis,” he never really presented his understanding of German society, its anti-Semitism, the rise of Hitler and Nazism, or the genocide itself. A partial exception was his blistering response to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem (especially her uncharitable depiction of the Jewish councils as collaborators). To be sure, he often did ponder its after-effects. Thus, his 1948 essay “The Star of David: History of a Symbol,” published shortly after Israel’s declaration of independence, argued that the symbol of the yellow star “which in our own days has been sanctified by suffering and dread has become worthy of illuminating the path to life and reconstruction.” For the most part, however, he claimed that the necessary distance for any kind of historical perspective had not yet arrived. Amir Engel, who puts special emphasis on the “Star” essay, claims that the personal pain was so great that Scholem turned to the more distant past “because he could not keep his eyes on the catastrophe of the present.”

Yet, some of his biographers suggest a definite influence of the Holocaust on his writings, albeit a more subtle and coded one. In different ways, they suggest that Scholem hinted at possible responses to Nazism in his earlier studies of Lurianic Kabbalah and Sabbateanism, which he regarded as creative if problematic answers to the expulsion from Spain. Scholem’s “Redemption Through Sin,” Biale suggests, can “be read against the backdrop of the political catastrophe of the 1930s.”

It is hard to escape the feeling that the way Scholem described Jacob Frank, the demonic “tyrant,” pointed toward a much more demonic figure on the contemporary stage. . . . The historical catastrophe of the expulsion from Spain now seemed to foreshadow a world in which God was hidden and nihilism unleashed.

And yet, as Biale also recognizes, the historical activism of the Sabbatean movement—a willingness to “force the end”—seems to foreshadow the secular Zionist return to history in some of Scholem’s writings.

Amir Engel claims to have “demystified” his subject by seamlessly connecting, if not reducing, Scholem’s scholarship to his personal, political, and historical context; Engel regards this as his “most substantial finding.” Scholem, he argues, did not discover metaphysical truths in the Kabbalah; rather, “he organized pliable textual materials according to his already given concepts.” But, to return to the ideal or “ultimate” biography, such an argument would require the biographer to engage more closely with Scholem’s readings of this textual material in a far more detailed and subtle way.

In 1979, David Biale penned Gershom Scholem: Kabbalah and Counter-History, the first—and still unsurpassed—systematic exposition of Scholem’s thought. In his new book, he employs the diaries and letters (and decades of reading, writing, and thinking about Scholem) to “enter into his inner life and view him not only as a thinker and writer but also as a human being.” Thus, he shows that the years 1934–1936 were a period of profound personal turmoil for Scholem, in which his first marriage collapsed, and a time in which “he found himself buffeted by profound romantic emotions . . . [and] felt deep guilt about his behavior in his personal relationships.” He goes on to argue that the remarkable rhetoric of “Redemption Through Sin” and Scholem’s simultaneous attraction and repulsion toward Jacob Frank found therein might not only reflect the tumultuous world history of the time but also “be a projection onto history of its author’s own innermost struggles.” Whether and how to make such speculative leaps constitutes the great quandary facing all biographers. To what extent can one gauge another person’s interiority and the ways in which it is externally expressed? Scholem himself once commented that, “I don’t understand my own depths and am clever enough to accept this.” Still, a biography devoid of inner life would be sterile. And surely, in Scholem’s case, such leaps are unavoidable given the diary entries in which he recorded his suicidal thoughts, conceits, insecurities, depressions, messianic pretensions, and intense personal attachments and animosities. On their basis, Biale also questions whether Scholem’s exemption from German military service on psychological grounds, which he always described as the result of a ruse, was a reflection of real mental instability.

Biale’s book is a fresh, often surprising depiction of Scholem. He shows us the vulnerable man behind the sovereign scholar without reducing the one to the other or relinquishing his admiration. Scholem’s tombstone describes him as “a man of the Third Aliyah,” an aliyah generally associated with Zionist pioneers, not philologists, but Biale concludes that “this Germanic scholar in his suit and tie . . . too, dug deep into arid soil to bring forth a world both strange and wondrous.”

George Prochnik’s Stranger in a Strange Land: Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem evinces a more wide-eyed admiration. Written as a kind of dual nonfiction Bildungsroman, Prochnik interweaves a vivid account of Scholem’s life with that of his own. It is through the prism of Scholem’s magnetic attraction that Prochnik recounts his youth, marriage, and spiritual quest in Jerusalem. Here Scholem becomes the model and foil for self-exploration. Some may regard this as a rather presumptuous, even narcissistic exercise, yet this narrative approach, together with Prochnik’s writerly skill, enables him to bring Scholem to life in often unexpected and insightful ways. If Amir Engel controversially regards Scholem’s scholarship as a set of modern myths and “stories” for carving out his identity and informing our times, Prochnik evokes the remarkable inventiveness and the deeply spiritual yearning for redemption that underlay Scholem’s lifelong scholarly quest.

As the title of Noam Zadoff’s Gershom Scholem: From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back suggests, it is perhaps the most revisionist of these biographies. Scholem titled his famous memoir of his early life From Berlin to Jerusalem, but, Zadoff asks, why did he end his story with his immigration to Palestine in 1923, when it was really just beginning? His answer is that Scholem’s Zionist turning point was “not as final and decisive as he had presented it.” Scholem’s personal and intellectual formation took place not only in Germany, Zadoff argues; he became increasingly disillusioned with the Zionist project over his years in Israel. As Zadoff shows, from 1949 until the end of his life he returned, to some extent, to “Berlin,” that is to the European and German intellectual life where he felt very much at ease.

A central aspect of this “return” to Europe was his participation in the annual Eranos conferences, held in Ascona, Switzerland, which he attended from 1949 until almost the end of his life. These conferences were held under the intellectual influence of Carl Gustav Jung, and Scholem had some initial qualms about participating because of Jung’s early ideological dalliance with the Nazis. That Scholem overcame them, Zadoff argues, is evidence of his desire to speak with and to fellow European intellectuals. Many of the classic synthetic essays Scholem published later in his life began as Eranos addresses delivered in beautifully polished German. Indeed, his last Hebrew book appeared in 1957!

As time went by, he was bountifully awarded and feted by German institutions and intellectuals. In his various guises as a German Jew, Israeli, Judaic scholar, and powerful intellectual presence, he was increasingly regarded as a post-Nazi moral authority, an exemplar of a lost humanist tradition. Overcoming his initial ambivalence, Scholem felt more and more at home in Europe. This is a biographically understandable, interesting, and important corrective to the standard Scholem story, but one should not take it too far. His travel schedule and political disappointments notwithstanding, he remained fully committed to the intense Jewish and Zionist world of “Jerusalem.”

But this discussion misses a critical element. From late adolescence until the end of his life, Scholem had a highly idiosyncratic metatheological vision of Zionism, one that combined total commitment with fierce disdain for all those who disagreed. Even from within his own sworn allegiances, as Prochnik notes, Scholem always needed to think against. “I want something completely different from all other Zionists,” he wrote in 1918, and that remained true. At all times then, he wove together fanatical fidelity with unrestrained recrimination. These two poles of his thought and personality—the utopian and the critical—coexisted in permanent tension. Indeed, that very tension is reflected in the differing interpretations of Scholem’s Zionist legacy, from the political right and left. Yoram Hazony, employing the pursuit of Jewish state sovereignty as the absolute Zionist yardstick, has powerfully attacked Scholem and fellow Brit Shalom intellectuals as betrayers of the Zionist cause. Yet many of Scholem’s students became supporters of the settler movement. Critics on the left claim this was no accident, given that Scholem’s world was animated by “irrationalist” categories such as myth, nihilism, the demonic, and antinomianism. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin has argued that while repeatedly warning against political messianism, Scholem “delineated Zionism in terms of a utopian return to Zion (namely, in messianic language).” That singular emphasis on Jewish return and redemption, he argues, prevented a necessary sensitivity to the plight of the Palestinians.

Scholem’s enduring charisma, one might almost say his aura, is related to the fact that he was essentially a European intellectual who brought his sparkling intelligence and categories of explanation to a radically new vision, a metamyth, of Judaism and propounded it from Jerusalem, of all places. As Prochnik puts it, “Scholem imported from Weimar Germany to Mandate Palestine a way of reading Jerusalem itself as a construct of Central European thought.” More specifically, although Scholem resembled fellow exiled Jewish intellectuals of his generation such as Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Hannah Arendt, and Leo Strauss, who have been similarly lionized (and who were his real interlocutors), he was the only one of them who chose Zionism and Israel. Their common suspicion of bourgeois conventions, their postliberal sensibility, their rejection of all orthodoxies, and their fascination with esotericism was (and continue to be) attractive to those convinced that conventional approaches to the modern predicament were (and are) not viable. All sought novel answers to what they regarded as the bankruptcy of 20th-century civilization and its ideological options.

Perhaps too, Scholem’s fascination for contemporary audiences is linked to a certain affinity between his concentration on textuality, rupture, paradox, the abyss, and the doubts and ironies of our postmodern world. But, in contrast to the postmodernists, Scholem maintained his belief in ultimacy, in the possibility of redemption. “A remnant of theocratic hope,” he wrote, “accompanies that reentry into world history of the Jewish people that at the same time signifies the truly Utopian return to its own history.” Yet this hope was always combined with a delicious subversiveness, as he remarked when he was nearly 80: “I have never stopped believing that the element of destruction, with all the potential nihilism in it, has always been the basis of positive

Utopian hope.”

Never a conventional historian, Scholem can be credited, Prochnik writes, “with pushing intellectual history and scholarly metaphysics toward a kind of lyric sublime.” Which other historian could write without embarrassment that redemption was not messianism “secularized as the belief in progress . . . It is rather transcendence breaking in upon history, an intrusion in which history itself perishes, transformed in its ruin because it is struck by a beam of light shining into it from an outside source”?

Many aspects of Scholem’s kabbalistic scholarship have come under fire, and, as with all giants, there are those who seek to chip away at his legacy. Viewed from the present, his emphasis on messianic myth, the demonic, and the irrational point to political dangers about which he warned, but in subtle, perhaps unintentional ways encouraged. Yet, for all that, he remains a titanic figure. He came onto the scene at critical flashpoints of European and Jewish history and left an indelible mark. Upon Scholem’s death, the philosopher Hans Jonas wrote: “He was the focal point. Wherever he was, you found the center, the active force, a generator which constantly charged itself; he was what Goethe called an Urphänomen.” Will we ever see his like again?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Man’s Learning Moves Me

Isaac Casaubon, the Hellenist who loved Hebrew.

Workday Jews

In their respective books, Chad Alan Goldberg and Eliyahu Stern address the question of whether the Jews are the quintessentially modern people or a people who came to modernity late and with a sudden shock. They reach very different conclusions.

A Neoplatonic Affair

As the tapestry of Hillel Halkin's first novel unfurls, we see how perfectly each part fits into the larger pattern.

“Repent, Repent”

In his new book, How Repentance Became Biblical: Judaism, Christianity, and the Interpretation of Scripture, David A. Lambert argues that repentance, as we understand it today, is absent from the Hebrew Bible.

somesuchme

much fodder for thought and argument

gershonhepner

GERSHOM SCHOLEM AND THE GOLEM ATTRIBUTED TO MAHARAL OF PRAGUE

Asked if the quarry he pursued

was all the time in the pursuer, Gershom Scholem

replied that many he had wooed

had been invented by him, which reminds me of the golem

they say was made by Maharal

in Prague, a legend based on information that was fake,

but I say life would be most dull

if we did not give our imagination a big break.

gershonhepnergmail.com