Missing Notes

“Today you can find her in Ashkelon near the welfare office / The smell of leftover sardine tins on a wobbly three-legged table / Kingly rugs stacked on a Jewish Agency bed,” wrote the Hebrew poet Erez Bitton in his “Song of Zohra el-Fassiya,” describing a real encounter he had with the great Moroccan singer in the late 1960s. “And she, in a fading housecoat / Lingers for hours at the mirror / Wearing cheap makeup / And when she says, ‘Mohammed the Fifth, apple of our eye’ / You don’t understand at first.”

When I encountered that famous poem, I didn’t understand at first either. The main character, garish and lonely, torn from some grand life and reduced to an Israeli tenement, was clearly an echo of something important that had once existed. But what was it?

That question, which matters a great deal for anyone trying to understand Israel, the Middle East, and the contemporary Jewish world, is answered with great skill in Recording History: Jews, Muslims, and Music across Twentieth-Century North Africa, by the music historian Christopher Silver. I’ve been following Silver on Twitter for years as his account, @Gharamophone, has kept followers abreast of his finds of rare records from North Africa and as he’s pieced together the forgotten history now expertly presented in this book. For Silver, music is a way to turn the spotlight on the kinds of people usually kept off the historical stage. His account unfolds in clubs and smoky halls, or in living rooms with family and friends gathered around the phonograph. The stars are the golden-voiced daughters and sons of the Jewish slums of Tunis, or oud wizards from the wrong side of Casablanca. “My goal,” he writes, “is to render audible a Jewish-Muslim past which has been quieted for far too long.”

Recording History introduces us to the musical world of the Maghreb in the first half of the twentieth century, and specifically to the Jewish performers and talent scouts who shaped the sounds heard by millions of Moroccans, Algerians, and Tunisians. Jews were central players in the Arabic music scene, moving back and forth over ethnic lines and between the concert hall and the synagogue in a way that now seems remarkable. We meet figures like Edmond Nathan Yafil, a Jewish mandolin player from the casbah of Algiers who collected hundreds of beloved local melodies in a 1904 compendium that was the first of its kind. Yafil also mentored dozens of musicians—Jews and Muslims—conducted the radio orchestra, and steered Algeria’s new recording industry in the first decades of the twentieth century. That was when new phonograph technology allowed local sounds to be first committed to shellac records and when music companies like the British Gramophone and the French Pathé discovered the Arab market.

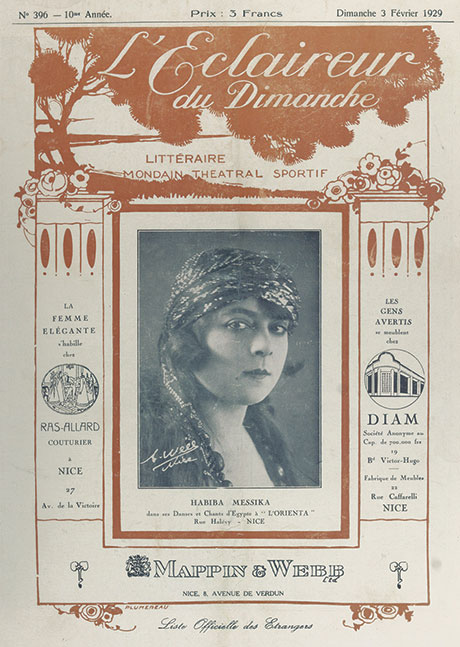

Silver’s memorable cast of characters includes the Tunisian singer Habiba Messika, a star with a flapper hairdo who was revered across French North Africa in the 1920s and helped inspire the nationalist sentiment that would eventually lead to independence. (Messika wouldn’t live to see it, however: she was the victim of a spectacular murder in 1930, when she was just twenty-seven.) We meet Acher Mizrahi, born in Jerusalem and transplanted to the Jewish Quarter of Tunis, who was somehow a synagogue cantor, a teacher at a religious school, and the author of the suggestive pop hit “Où vous étiez mademoiselle.” It was the kind of thing that made sense at the time—like the fact that in 1933, the star Dalila Taliana, whose real name isn’t known and who might have been Catholic but might have been Jewish, performed that song in Algiers for a Muslim audience marking Lailat al-Qadr, one of the high points of the holy month of Ramadan. All of this comes to life memorably in Silver’s energetic and concise book, demonstrating, as the author tells us, “that music remembers much of what history has forgotten.”

It may surprise many readers to learn that some of the voices most closely identified with the North African independence movements belonged to Jews. Messika’s 1928 version of an anti-British Egyptian anthem was considered so dangerous, for example, that it drew the attention of French security agents. A small-time Moroccan street entrepreneur, a certain Mustapha Lemcharfi, was actually hauled in by police for renting out phonographs with her records: this music, authorities warned, “had the effect of ‘stir[ring] up Arab feelings.’”

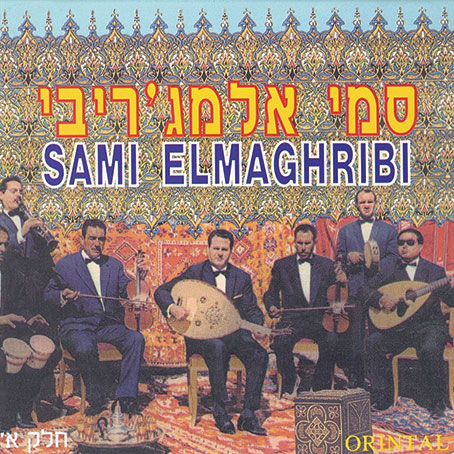

A Jewish superstar of 1930s Morocco, Lili Labassi (whose real name was Elie Moyal) was also suspected of agitation after one of his love songs was interpreted by French police as support for a nationalist leader they’d banished to the Sahara. And later, with French control finally waning after World War II, Moroccan aspirations for independence became associated with the voice of Samy Elmaghribi, or “Samy of the Maghreb.” A crooner with a shiny pompadour and close ties to the royal court, Samy’s real name was Salomon Amzallag. For a while, he was the country’s biggest star and the local front man for Coca-Cola, Gillette, Palmolive, and Canada Dry. When ordinary Moroccans imagined freedom from French rule, Silver writes, “it may have sounded like Elmaghribi.”

For the Jews of North Africa, the end commenced with the surrender of France to Nazi Germany in 1940 and the move of France’s colonial possessions to the control of the puppet Vichy regime. French officials in North Africa instituted race laws, barred Jews from many professions and schools, and sent some to internment camps. Some who were unlucky enough to be caught in metropolitan France were sent to the gas chambers, like the Tunisian composer Gaston Bsiri, murdered in 1942. The singer Salim Halali was hidden at the Grand Mosque of Paris, apparently by an imam who was a music enthusiast, but his sister and her child were arrested by French police and killed at Auschwitz.

After 1940, the native Jewish musicians who’d been at the center of the Arab scene, and who were now barred from it by law, watched many of their Muslim friends and colleagues betray them. Cultural officials accused them of importing “decadence” into Arabic music and of appropriating a culture that was foreign to them. Magazines published vicious musical critiques of their work alongside the regime’s new anti-Jewish laws. Mahiedinne Bachetarzi, for decades a protégé of the famed Jewish impresario Yafil, now moved to center stage and wrote a song of exuberant praise for Vichy and its dictator, Marshal Pétain: “Say it with Me (Long Live the Marshal).” The author describes Bachetarzi touring with another Muslim artist, Rachid Ksentini, who had performed until recently with a Jewish comedienne, Marie Soussan. With Soussan now legally forbidden to perform, her former partner “lauded Pétain and his ‘national revolution.’” Closing one show in Bougie, Algeria, the same Bachetarzi who’d once praised Yafil as his musical “master” now warned the audience to be “on guard against the schemes of the Jews . . . who, while our masters, never stopped sinking their teeth into us and who, now downgraded, caress us as brothers.”

Even when Vichy was defeated, and with the French finally on their way out of North Africa after the war, many Jews began to grasp that their enthusiasm for independence might not be reciprocated. A Moroccan nationalist leader spoke of the country’s “Arabo-Islamic destiny,” and the pro–independence party Istiqlal launched an “anti-Zionist” campaign that was actually a boycott of Jewish businesses. When things came to a head with the creation of the State of Israel, 2,500 miles away from Casablanca, Muslim mobs killed forty-two of their Moroccan Jewish neighbors and caused millions of francs in damage to Jewish property. The Jewish world inside the Islamic world, which numbered perhaps a million people at the time and included Jewish quarters in most major Arab cities, was ending.

But it didn’t end all at once, and the direction of events wasn’t always clear. In another important contribution, Silver shows how in the postwar years, which are now usually viewed by chroniclers of Jewish history mainly through the lens of mass exodus, there were other trends in play. The rise of the Jewish star Elmaghribi, for example, came in precisely those years: the singer’s own siblings decamped to France, but he held on, performing for King Muhammad V of Morocco and enjoying the adulation of his Muslim fans. The famous Zohra el-Fassiya, dame of Moroccan song, was still packing concert halls throughout the 1950s and, as she later told the Israeli poet Erez Bitton, was still a regular at court.

But fate made itself clear within a few years. In 1961, the beloved Algerian Jewish singer Raymond Leyris was shot in the neck and killed in Constantine while out for a walk with his daughter. The assassins were never caught, but this was at the height of Algeria’s independence war against France, and they are assumed to have been Muslim liberation fighters. The following year, el-Fassiya left for Israel, where two of her children were already living, along with hundreds of thousands of other transplants from North Africa.

Her music didn’t find a home in the new state, however, at least not then: in the final tragedy of that generation of Maghrebi Jews, Israel’s eastern European founders found their culture strange and primitive and too reminiscent of the Arab enemy. El-Fassiya ended her life in obscurity and was immortalized in her penury by Bitton’s poem, which made her a symbol of what had been lost.

The music, or an altered and Israelified version of it, would ultimately reappear after a generation or two underground in the pop genre known broadly as Mizrahi (“Eastern”), in the work of crossover artists like Kobi Oz of Teapacks and in projects like the Jerusalem East and West Orchestra, conducted by Tom Cohen, the gifted young heir of the great Yafil. In the decades when the sound sojourned in Israel’s cultural wilderness, it was kept alive by performers with stage names like Sheikh Muijo and Pétit Armand (father of the Mizrahi star Kobi Peretz), who performed in small clubs and private homes, and by scrappy musical hustlers like Raphael Azoulay of Jaffa. The latter started his record business by buying popular Egyptian records from Palestinian Arab distributors and selling them to Jewish arrivals from Arab countries—a story that encapsulates one of the most important observations one can make about Israel, which is that the country’s story is not just about a revolution in Jewish history but also about the stubborn continuation of Jewish life in the Arab world.

In 1965, three years after el-Fassiya’s departure, Elmaghribi sold his legendary record store in Casablanca, Samyphone, and lived the rest of his life in Montreal. There, he was known not as the pop star “Samy of the Maghreb” but as the respected cantor Salomon Amzallag. The sale of his store marked the end of an era, one that was swallowed amid the bloodier Jewish catastrophes of the twentieth century and has never been sufficiently mourned or even understood. Christopher Silver’s noble quest to bring this lost world back to life, via obscure Maghrebi music stores and dusty boxes of shellac records in Montreal and Paris, allows us to restore its missing notes and fill in a silence in the soundtrack of our history.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Homer of Lod: The Indispensability of Erez Bitton

The blind writer from Algeria is one of Israel’s most important voices, both in poetry and in policy.

Memories of Morocco

In the 1940s Moroccan Jews were still sacrificing a bull on the Sultan’s doorstep. There was a deep cultural symbiosis of Jews and Muslims in North Africa.

North Africa during World War II

Mentions of wartime North Africa conjures up visions of Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains in Casablanca. It was far worse than that...

Sephardi Lives: From Ottoman Salonica to Rosario, Argentina

Singing women spark indignation in Salonica, a change of seasons in Argentina requires rabbinic expertise, and Jews in the Ottoman army get fat and happy.

david l wilson

The review focuses almost exclusively on Moracco. Algerian Jewish musicians were numerous and very popular throughout the Maghreb and in metropolitan France.

I will seek out the book. The sadness of the rejection of the Jews in the former French colonies is the injury. The insult was the reaction in the early 50's in the new state of Israel to Mizrahi music.