Solidarity and Democracy

Now, more than ever, it seems as if the lack of a constitution is a great flaw in the Israeli political system. When the United Nations voted in 1947 to partition Palestine and establish a Jewish state, it required its future citizens to immediately form a constituent assembly that would draft a democratic constitution. The first Knesset, elected in 1949, took up the baton, but it didn’t follow through. Why not?

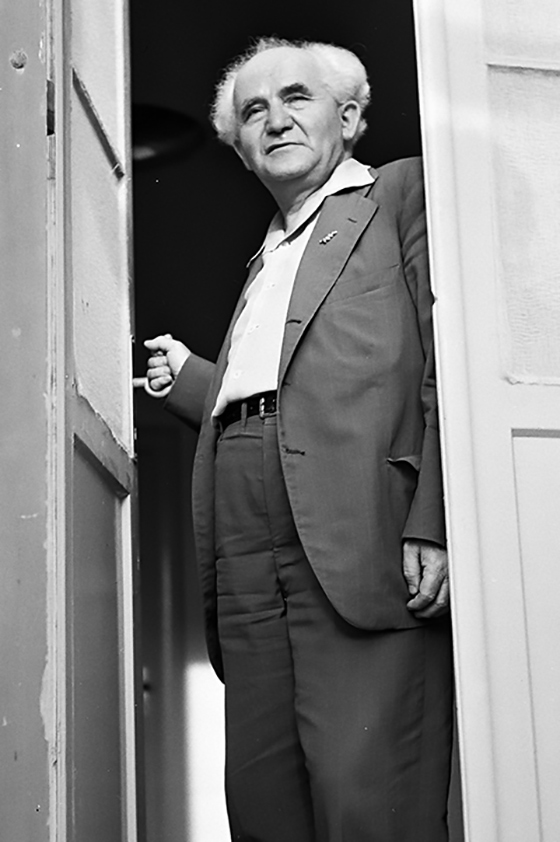

Many place the blame on David Ben-Gurion’s desire to concentrate as much power as possible in the prime minister’s office. But this is too simplistic. Ben-Gurion did effectively terminate constitutional discussion for a long time, but he had real, public-spirited reasons for doing so. No one has elucidated them as astutely as Nir Kedar, a prominent Israeli law professor and the president of Sapir College, both in his 2015 Hebrew volume, Ben-Gurion veha-Hukah (Ben-Gurion and the Constitution), and, much more concisely, in what is in large measure an adaptation of that book, Ben-Gurion and the Foundation of Israeli Democracy. In both books, Kedar recapitulates and analyzes Ben-Gurion’s seminal vision of the democratic state that he did so much to hammer into reality.

Kedar argues that Ben-Gurion’s primary reason for opposing a written constitution was his fear that the attempt on the part of a society as fragmented as Israel’s to produce one would be both divisive and unproductive. Why should the Left and the Right, the secular and the religious, waste their time trying to resolve complex political-philosophical questions when there were so many immigrants to absorb and a country to build? Nevertheless, Kedar writes, “for tactical reasons, the first argument he presented to the public was that a constitution was not a necessary condition for a democratic, law-abiding state.”

This wasn’t duplicitous—Ben-Gurion was genuinely committed to democracy and did not believe that it needed to be tempered to prevent unwise majorities from going astray. He saw little need or justification for American-style checks and balances. What was necessary was to have legally grounded institutions that enabled the people to express its will and laws that respected individual rights.

Ben-Gurion was particularly critical of constitutions that were difficult to amend. He believed, as Kedar puts it:

That it was inappropriate and illogical for one generation to bind a future one with a law that could not be changed by means of a majoritarian democratic decision.

Or to put it in the words of the “old man” himself:

Can we be sure that those who come after us will not have as much intelligence, as much loyalty as we do, that they will not understand the nation’s values as we do? Why should we constrain them?

As Kedar notes, Ben-Gurion thought that “the American courts’ authority to declare laws passed by Congress unconstitutional was ‘a terrible power’ detrimental to American democracy—’a reactionary step, a simple attempt to hold back the progress of democratic legislation in the state.'”

This is close to the spirit of the Likud-led government’s current efforts to restrict the powers of the Israeli Supreme Court—closer, in fact, than anything said then by the Likud’s founder, Menachem Begin, who argued forcefully for the adoption of a constitution, not least because it could help protect the rights of individuals against a tyrannical majority. But before we conclude that Yariv Levin and Simcha Rothman are, ironically, channeling Ben-Gurion, we should compare their positions on the nomination of Supreme Court justices. In 1953, Ben-Gurion’s government instituted the unique system that gives jurists, not politicians, “a built-in majority” in their selection to maximize the justices’ independence from the world of politics. Levin and Rothman are trying to replace this system with one that gives the governing coalition the dominant voice in the choice of justices.

For Ben-Gurion, an independent judiciary was just one part of his overall idea of how a democratic regime should operate. Ben-Gurion, Kedar insists, was not merely the political pragmatist he is generally assumed to be but “a statesman who really had a systematic concept of citizenship and civil society.” A narrow focus on his “determined and forceful way of getting things done obscures the fact that his policy in fact grew out of his ideas.”

If Ben-Gurion’s political theory had to be summed up in a single word, it would be one that is rather difficult to translate: mamlakhtiyut. Kedar, who wrote the book on the subject (in Hebrew), thinks that “civicism” is the best, if awkward, English equivalent. Derived from mamlakha, the Hebrew word for “kingdom,” it connotes the vital importance of the state, but as Kedar makes clear, Ben-Gurion’s focus on the collective did not override his individualism. Mamlakhtiyut, he writes, “is a political concept that sees the state . . . first and foremost as a framework that places the individual front and center.”

The individual here means all individuals, who should have the freedom to chart their own way in life while participating equally in their own governance. These convictions underlie Ben-Gurion’s insistence on the subordination of the army to democratic government, his strict commitment to the rule of law and freedom of expression, and his depoliticization of the civil service. However, mamlakhtiyut meant more than the empowerment and equality of all citizens; it is also concerned with the way that they relate to each other. They needed to be imbued with “a true sense of belonging to a civil society built on mutual responsibility.”

Kedar shows how, in the spirit of mamlakhtiyut, Ben-Gurion tried to bind Jews of disparate religious orientations and ethnic origins together as Israelis. This entailed, among other things, “tolerance of the religious practices of the new immigrants” in the state’s early years and “support of religious education for children of immigrants who desired it.” Readers who know something of the actual treatment accorded to new immigrants for Arabic-speaking lands in the early 1950s may scoff at these assertions. But they would be mostly wrong to do so.

It is true, as Kedar acknowledges, that Israeli officials of the time often viewed “religious education as an obstacle to progress and to the fashioning of a new Israeli identity free of the chains of the past.” They often tried to impose secular education on immigrant children in transit camps. But, as Kedar observes, “Ben-Gurion, in contrast, was much more accepting of the customs of the immigrants and their interest in having their children educated in a religious mold.” During an interparty debate in 1950, Ben-Gurion insisted:

The State of Israel, especially in this period, is not permitted to take children of a religiously observant background, who are able to receive a decent religious education, and enroll them in liberal-secular schools. . . . I am interested that the Labor Movement should rule Israel not as a dictatorship but by the power of the nation’s faith in it.

Mamlakhtiyut went only so far, however. In his final chapter, Kedar focuses on the people who marked “the boundaries of democracy, rule of law, and egalitarian citizenship”: Israel’s Arab citizens. Although Ben-Gurion “supported the equal participation of Arab citizens in Israeli democracy . . . he did not sincerely view Arabs as members of the Israeli demos, nor did he feel any sense of solidarity and partnership with them.”

Not unrelatedly, at the time Ben-Gurion was setting Israel’s policy with regard to its Arab inhabitants, the country was just emerging from a war in which it had been allied with the Arab nations that had tried to destroy it. “In the eyes of most Jews, the country’s Arab citizens were a fifth column who in time of war would join forces with invading Arab armies” in the expected next round of fighting. Shaping Israel’s policy toward them under such circumstances, Ben-Gurion found that “a democratic republic based on the equality of all citizens and the rule of law was difficult to achieve.” He didn’t bend over backward to do so. Until the end of his tenure as prime minister (and for another three years), the Arabs of Israel continued to live under military government.

Indeed, Kedar writes, “Israel’s Arab citizens have never been considered true and equal partners in the Israeli demos; they have remained aliens in their own land, excluded from centers of power and discriminated against.” Kedar does not mince words, but neither does he point a finger. He is interested not in leveling criticism or in parrying it but in pinpointing responsibility, or rather, in deflecting it from Israel’s political system itself to the people who have been in charge of it.

There are those, Kedar notes, who believe that Israel’s less than fully equal treatment of its Arab citizens is the result of its inherent flaws, in particular its lack of a robust constitution. But Kedar argues that this misunderstands the nature of the problem:

Severe ethno-national discrimination existed in Israel despite its advanced democratic institutions and its commitment to the rule of law and the civil republican (mamlakhti) ethos so deeply rooted in Israeli Jewish society. Seen in this way, discriminatory treatment of Arabs did not derive from a lack of mamlakhtiyut and democracy. Rather, it demonstrates their limitations.

The fact that Ben-Gurion fell victim to his biases and discriminated against Israeli Arabs does not, in Kedar’s eyes, vitiate his achievements. In part, this is because “adhering to the principles of democracy and equal and inclusive citizenship” that he established “are the only hope, and the principal mechanism, for achieving free and true equal partnership for all Israel’s inhabitants.”

In crediting Ben-Gurion with laying the groundwork for the more open and democratic society that eventually came into being, Kedar sounds a little like the American political scientists who have celebrated Thomas Jefferson’s intellectual contributions to the spread of liberty despite his having been a slaveholder. In my own opinion, these people are correct about America’s past, and Kedar is likewise correct about Israel’s. But what about the future?

Kedar clearly hopes, albeit guardedly, for improvements that will continue the best trends of the recent past. But it is difficult to hope now, as he does, for the expansion of mamlakhtiyut to more fully encompass Israel’s Arab citizens at a time when the very idea of a common civic culture seems to be contracting.

In a new documentary series, Medurat ha-shvatim (The Campfire of the Tribes), introduced in May by Israel’s Channel 11, its narrator intones regarding the country’s first fifty years:

In spite of the social gaps it still seemed as if the social glue stuck and Israeli mamlakhtiyut was strong enough. In the next generation, however, it looks as if the glue is weakening. Israel today is made up of different tribes. Every tribe has its story, every tribe has its fears, and every tribe has its truth. Every tribe sits around its own campfire and recites what happened to it in a story that turns into its own historical truth.

Whether the glue binding the different tribes of Israel together was in the past as strong as The Campfire of the Tribes suggests is debatable. But the evidence that it is rapidly losing a lot of its adhesive power is easy enough to see.

Nir Kedar’s new book doesn’t pretend to explain how Israeli solidaritycan be strengthened in the future. Nor does he address the question of whether Israel should, three-quarters of a century into its existence as a state, make a renewed effort to adopt a formal constitution. But he does make an important contribution to our understanding of how Ben-

Gurion’s democratic vision shaped Israel, even if it fell short of some of its highest goals.

Suggested Reading

Wishful Republic

What lessons can be learned from the city of Haifa, and what does its culture suggest about the likelihood and limitations of a binational state?

Missing Menachem

When Menachem Begin led the Likud to victory in 1977, Yitzhak Ben-Aharon spoke for many in the Israeli political establishment when he said that “if this is the will of the people, we have to replace the people.” Begin’s image has evolved, but he remains a contested figure.

Our Man in Beirut

The Arab Section, suggests Matti Friedman, in one of his latest book's nicer lines, “needed men idealistic enough to risk their lives for free, but deceitful enough to make good spies.”

Fauda: The Wages of Chaos

Fauda, which takes its name from the Arabic word for chaos, opens in an adrenaline rush of noise, confusion, and jagged camerawork.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In