Dionysus and the Schlemiel

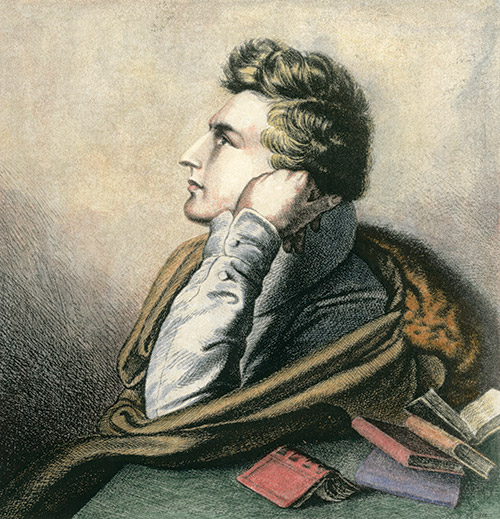

In her youth, Freud’s grandmother attended a dinner party at the home of Heinrich Heine’s wealthy uncle Solomon, where the diminutive young poet sat awkwardly, ignored and stewing in humiliation. Every biographer believes, although none can prove, that as a young man Heine fell desperately and unrequitedly in love with his cousin, Solomon’s daughter—probably with both of Solomon’s daughters. Heine, whose father faltered in business, certainly fell in love with Solomon’s wealth, which he coveted to an insane degree. The bitterness of Heine’s romantic predicament presumably inspired some of his early lyrics—like “Die Lorelei”—which proved irresistible to the composers of German lieder and famously frustrated the efforts of Nazi censors to purge writing by Jews from the German literary canon.

Freud shared his grandmother’s anecdote in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, in which he took Heine as his leading example of Jewish comic genius. But my favorite joke about Heine’s Jewish identity comes from Kafka. In exile in France, Heine married a nineteen-year-old Parisian shopgirl whom he nicknamed “Mathilde”—a devout Catholic whose simplemindedness scandalized his friends. In one of his letters to Milena, Kafka imagines a scene in which Mathilde is railing against her husband’s ill-mannered German friends when she is contradicted by the Austrian poet Alfred Meissner. “But you don’t know the Germans at all,” he says. “After all,” Meissner insists, ticking off the names of Jewish friends in Heine’s circle, “the only people Heinrich sees are journalists, and here in Paris all of them are Jewish.” The incredulous Mathilde throws up her hands: “In the end you’ll claim that Kohn is a Jewish name too, but Kohn is one of Heinrich’s nephews and Heinrich is Lutheran.”

The joke was as much on Heine as on the childlike Mathilde. Born Henry Heine in Düsseldorf in 1797, Heine came of age under the brief-lived liberal dispensation of Napoleonic rule. He attended Catholic schools and went on to study law, a profession subsequently closed to Jews when the French were driven out. His Jewish education was largely belated, a consequence of his membership as a young man in the short-lived Verein für Kulture und Wissenschaft der Juden (Society for Jewish Culture and Science), essentially a volunteer Judaic studies department without a university. The Verein fell apart when its founder, Eduard Gans, converted to Christianity to teach legal history at the University of Berlin. Heine, after a brief internal struggle, had made the same choice a few months earlier, also in the hopes of obtaining an academic position, though it never materialized. His conversion to Lutheranism, he remarked, had been less painful than having a tooth pulled, but it left a bitter taste in his mouth, which he exorcised in relentless satirical portraits of “baptized Jews.”

I wish George Prochnik had included Freud’s anecdote—and Kafka’s, even if it was apocryphal—in his lively new biography, Heinrich Heine: Writing the Revolution, but no biography of Heine could possibly satisfy the demands of every Heine reader. Indeed, Heine is a particularly challenging subject for biographical study. A satirical sharpshooter whose own coordinates shifted with the occasion, he viciously skewered others for the character flaws he shared with them. There was something fundamentally performative about his personality. Prochnik tries to channel Heine’s inner voice but largely gives us Heine’s self-presentation, which is all Heine ever gave us. The mask never came off unless to make way for a new mask, a new persona.

That doesn’t make the narrative of his life any less fascinating. As Prochnik’s subtitle suggests, Heine’s career was punctuated and nearly bookended by political revolutions. He was eight years old when Napoleon’s army occupied Düsseldorf, a day he later immortalized in his prose masterpiece, Das Buch Le Grand. In his early thirties, he moved to Paris to join in the July Revolution, which he would chronicle in his voluminous journalism. His writings were censored and then banned in Germany, as was his person. He had to sneak into the country to visit his aging mother. In the revolutionary year of 1848, overtaken by the symptoms of late-stage syphilis, he dragged himself from his bed into the boulevard, amid street fighting, only to seek shelter in the Louvre, where he collapsed, weeping, before the Venus de Milo. He never left his bed again. Paralyzed and half-blind, convulsed by spasms, he eventually required an assistant to lift his eyelid to read. For eight brutal and uncannily productive years, he wasted away on his “mattress crypt,” as he called it.

In France, Heine had held his Jewish heritage at arm’s length, casting himself as a “Hellenist”—a follower of Dionysus—and espousing a libertinism that was either feigned or largely hidden from view. In the opposing camp—“the Nazarenes”—he conveniently lumped together Jews and Christians alike, disowning both. But suffering, he now suggested, had stripped him down to his tragic and irreducible identity as a Jew. “I am no longer a divine biped,” he announced in the Augsburg Gazette in 1849, one year into his long-drawn-out deathbed ordeal. “All I am now is a poor Jew sick unto death, an emaciated image of wretchedness, an unhappy man.” To the astonishment and horror of his former friend Karl Marx, it soon became apparent that Heine had also embraced the idea of a personal God, more or less modeled on the God of his fathers.

Was Heine’s “return to God” sincere? The question is impossibly vexed by his genius for irony, which never abandoned him. Even his illness is presented as a joke orchestrated by the Divine Comedian—a creator made in his own image. Heine dubbed him “the Great Aristophanes of Heaven.” If his joke made Heine wince, he could at least admire its superior wit. “Alas, God’s mockery weighs heavily upon me,” he wrote near the end of his Confessions. “How miserably I trail behind Him when it comes to humor, to jesting, on a colossal scale!”

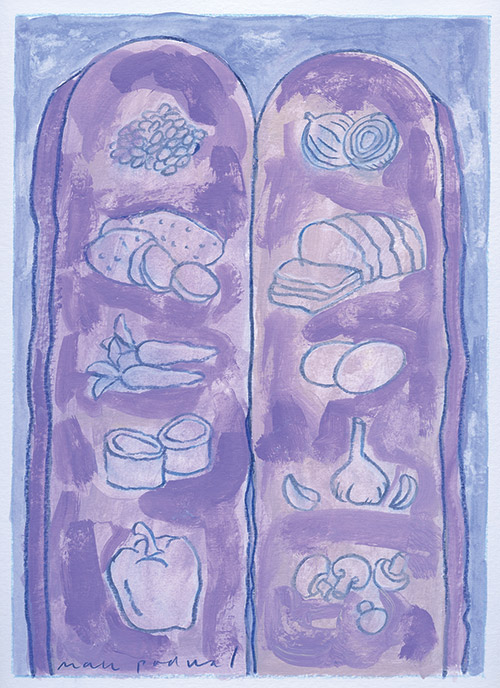

Written entirely from his mattress crypt, Heine’s outrageously inventive Hebrew Melodies is his most sustained poetic exploration of Jewish themes, and it would be difficult to overpraise its presentation in the luxurious edition recently published by Penn State University Press as volume 6 of its quirky, ambitious series Dimyonot: Jews and the Cultural Imagination. The wonderful translations by Stephen Mitchell and Jack Prelutsky embody Heine’s genius in a contemporary idiom, which happily coexists, in this edition, in parallel columns with the original German text. Poem and translation are supplemented by Mark Podwal’s witty, colorful paintings, which illustrate Heine’s extravagant whimsy in surprising ways. The book is a treasure.

“Princess Sabbath,” the first and shortest of the three interlocking poems that comprise Hebrew Melodies, is a hymn to the observant Jewish life Heine never lived. It depicts the transformative power of the Sabbath, as he imagines it, for a poor peddler named Israel.

The rituals that Heine respectfully depicts—the kissing of the mezuza, Kabbalat Shabbat, Havdalah—may have seemed almost as exotic to him as to his non-Jewish readers. He once claimed never to have stepped foot in a synagogue (a patent lie). But he never denied his firsthand knowledge of Jewish cuisine, perhaps the only element of his Jewish heritage for which he always expressed unadulterated enthusiasm. “Kuggel,” he wrote in a letter to a fellow member of the Verein: “has done more for the preservation of Judaism than all three issues of our journal.” Cholent, the most traditional Sabbath dish, was a particular favorite, and in “Princess Sabbath,” the slow-cooked stew is Israel’s substance of choice and its compensation for not being permitted to smoke on the Sabbath. At the poem’s climax, Heine launches into a mad, chauvinistic riff on Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”: “Schalet, schöner Götterfunken / Tochter aus Elysium!” Even in Mitchell’s translation, the choral movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which famously set Schiller’s lyrics to music, starts bubbling in one’s ear:

Cholent, light direct from heaven,

Daughter of Elysium!

Thus would Schiller’s ode have sounded

Had he ever tasted cholent.

Compared tocholent, “The ambrosia of the phony / Heathen gods of ancient Greece,” Heine concludes, is “Just a pile of devils’ droppings.” So much for Hellenism.

At twice the combined length of the two poems that flank it, “Yehuda ben Halévi” is in every sense the central poem of Hebrew Melodies and a high point of Heine’s art. It opens withthe words of Psalm 137, his favorite biblical text, swirling in his head: “If I ever should forget thee, / O Jerusalem, let my right hand / Lose its cunning, let my tongue / Cleave forever to my palate—.” Channeling collective memory from his sickbed trance, Heine hallucinates ghosts of bearded men from the Spanish Middle Ages, “ancient voices, chanting psalms.”

The central narrative of the poem—to the degree that it has one—is a verse biopic of the most renowned Hebrew poet of medieval Spain, famed for his late-in-life pilgrimage to Jerusalem. We hear how, from an early age, Halevi’s father educated him in halakha (“that tremendous / School of fencing”) and aggada (which Heine compares to the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, planted “in the air— / High up on colossal pillars” and “cunningly / Joined by countless hanging bridges”). The latter, in particular, contributes to Halevi’s rebirth as “a mighty poet”:

An immense and wonderful

Pillar of poetic fire

Moving out in front of Israel’s

Caravan of grief and anguish

In the wilderness of exile.

In Heine’s retelling, Halevi’s conversation with the legendary Wandering Jew inspires his pilgrimage to the ruins of Jerusalem, where—chanting his poem—he is murdered by an Arab horseman or perhaps taken up to heaven by an angel in disguise. In an irony he did not intend, Heine imagines Halevi’s soul ascending as a chorus of God’s angels flatter him by singing “the very verses / He had written for the Sabbath . . . Lécho, dodi, líkras kálle.” In fact, they were written by the Safed mystic Shlomo Alkabetz some four hundred years later—a little joke worthy of the Great Aristophanes of Heaven.

Other narratives and digressions abound, which, like the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon, are “cunningly / Joined by countless hanging bridges,” and weave together multiple traditions and historical periods. We trace, for instance, the provenance of a pearl necklace once given by “Smerdis / (The false one), to Queen Attosa,” which becomes the war booty of Alexander the Great after his victory over King Darius at the Battle of Arbela. Alexander gives it “To a very pretty Greek / Dancer by the name of Thaïs” with “lovely / Hair that streamed like a bacchante’s.” When she dies of “The Babylonian / Clap,” it passes through many hands to Cleopatra (who swallows one of its pearls in wine to impress Antony), to the caliph of Umáyyad Cordoba (who winds it around his turban), and to the Spanish Catholic queens (“Sitting on their balconies, they / Fanned themselves and took refreshment / In the smell of old Jews roasting”). The pearls currently may be found, Heine notes, “Shimmering on the neck” of the Baroness von Rothschild, a personal friend. Such are the ironic reversals of history.

Heine also tells the stories of Solomon ibn Gabirol and Moses ibn Ezra, two other “poets / From the glorious golden age of / Ancient Arab-Spanish-Jewish / Poetry, that school of genius.” Mitchell powerfully renders Heine’s eulogy for Gabirol, “This sincere and God-devoted / Troubadour, this passionately / Reverent Jewish Nightingale”:

Nightingale who tenderly

Sang out his resplendent love songs

In the densest darkness of the

Gothic medieval night.Undiscouraged and untroubled

By the goblins and the phantoms,

By the maze of death and madness.

After contemplating the evil fates of the great Jewish poets of the Spanish Middle Ages—not to mention his own sorry state—Heine concludes that all poets are schlemiels. Even Apollo, “the lofty Delphic god” of poetry, is “Though a god, a true shlemiel,” flinging his arms around the beautiful nymph Daphne and then finding himself hugging “some tree bark.” “Yes,” Heine insists, “the very laurel / That so proudly crowns his forehead / Is a sign of his shlemieldom.”

This revelation inspires a mock quest to discover the etymology of “schlemiel,” a Yiddish word that had been naturalized in German by the still-living author of Peter Schlemihl, Adelbert von Chamisso. Heine imagines catching up with Chamisso—“the dean of all schlemiels”—in Berlin, only to discover that he learned the word from Julius Eduard Hitzig, the director of the Criminal Counsel at the Berlin Supreme Court. Hitzig, a former acquaintance of Heine’s, was a descendant of the prominent German Jewish Itzig family, whose patriarch, Daniel, had been Frederick the Great’s banker and court Jew. Now a pious Lutheran, Julius had germanized his family name with an “H.” Heine pretends to explain this change in spelling as the consequence of a revelation: Julius’s vision of his surname “Blazoned in the heavens” but preceded by “the letter H.” “What is the meaning,” he asks himself, “Of this H?” “Perhaps,” he surmises, “Holy Itzig?” But fearing that “Holy,” although “a splendid title,” was “not suited / For Berlin,” he “took the name of Hitzig,” Heine explains, twisting the knife. When he greets Hitzig, Heine’s two etymological quests dovetail, in what might be mistaken for a rhetorical question:

“Holy Hitzig,” I addressed him

When I saw him, “would you tell me

What the etymology

Of the Yiddish word shlemiel is?”

After Mitchell’s success, I was prepared to be a little disappointed when I discovered that the third poem in Heine’s Hebrew Melodies—“Disputation”—had a different and less renowned translator, Jack Prelutsky, a poet and prize-winning author of children’s verse. But it is difficult to imagine a wittier and more natural rendering in English of Heine’s rhyming finale, a sort of satyr play that anticipates the outrageous comedy of Sacha Baron Cohen.

The disputation between Rabbi Judah of Navarre and the Franciscan Don José takes place in Toledo before Pedro the Cruel and is intentionally rife with anachronisms and absurdities. For instance, not only the Christians but their Jewish opponents, too, are confident of victory:

So convinced are the Franciscans

That the monk will take control,

They’ve prepared the holy water

And have filled the votive bowl.On the other hand, the Hebrews

Are completely unafraid

And show confidence by sharpening

The circumcision blade.

Heine takes a page from Shakespeare’s Shylock in these lines and also exacts his own revenge on the baptism to which he submitted as a young man to forward his career. (Podwal’s illustration depicts a trinity of silver Torah pointers holding open scissors.)

It would be misleading to suggest that Hebrew Melodies and the other Jewish-themed poems that Heine wrote from his deathbed marked a radical break with his previous work. Already, in his early twenties, under the influence of the Verein, he had begun to gather materials for a historical novel centered on a medieval blood libel. He eventually published the abandoned fragment of The Rabbi of Bacherach, with its powerful opening chapters, in 1840, when news of a contemporary blood libel reached him from Damascus. He was appalled by the injustice and worked assiduously to embarrass the French consul into taking action to protect the Syrian Jewish population.

Heine always insisted that his efforts on behalf of the persecuted Syrian Jews were dictated purely by his commitment to the ideals of the Enlightenment. But his sensitivity to the charge of special pleading often coincided with a form of Jewish shame, about which he could be shamelessly explicit. Jews, he once wrote, were “an accursed race who came out of Egypt, the homeland of crocodiles and priests, carrying with them, besides certain skin diseases and stolen vessels of gold and silver, a so-called positive religion and a so-called church.”

But if Judaism was a congenital disease, it is only logical that Heine would eventually succumb to it. “Fallen, smashed to pieces, / Lies my proud triumphal chariot,” he writes in “Yehuda ben Halévi,” and “I myself am / Writhing on the floor here, wretched, / Crippled and in anguish.” Once drawn by leopards and accompanied by dancing women and song, Heine’s broken chariot clearly belongs to the Greek god Dionysus.

Hellenism was the sword with which Heine had attempted to cut the Gordian knot of his tangled Jewish identity. But in the end, his Hellenism fared no better than his Lutheranism. Heine’s Jewishness—like that of Kafka and Freud—proved as inescapable as it was amorphous.

Suggested Reading

“Where They Have Burned Books, They Will End Up Burning People”

The surprising source for Heine’s prophetic remark that “where they have burned books, they will end up burning people” is a play about the fate of Muslims in Christian Spain.

Funny How a Poem Can Get Under Your Skin

On Celia Dropkin’s avant-garde Yiddish break-up poem and a political insight.

Seeds of Subversion

The "Other" Jewish tradition.

Orpheus on the Lower East Side

Hart Crane’s name will forever be linked to Samuel Greenberg’s by a brilliant act of plagiarism, for the story of Greenberg’s posthumous manuscripts is almost as remarkable as the poetry itself.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In