Funny How a Poem Can Get Under Your Skin

I first read the Yiddish poems of Celia Dropkin when I befriended her granddaughter Franny in New York in the late 1950s. Franny’s father John, one of Celia’s five children, lived in Brooklyn and was a professor of physics, but I don’t think either he or any of Celia’s children or grandchildren read her in the original. Though I had not yet begun graduate studies in Yiddish literature I was already familiar with its contours, so the family was happy to learn that I was interested in their forebear just as I was happy to know a Yiddish writer’s offspring. The poems were passionate and personal, and it tickled me that in the 1920s their “granny” was more erotically adventurous than we were.

Celia was one of a number of American Yiddish women poets who broke into literature at about the same time. New York had become an incubator of Yiddish poetry around 1907 when Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe was at its height. A group calling itself Di Yunge (The Young) said it was giving up the national and social functions of Yiddish writing, by which its members meant that they no longer wanted to produce poetry and stories for di masn in di gasn—the masses in the streets. They insisted that just because they wrote in Yiddish they were not necessarily confined to writing as Jews any more than every English poet was obliged to hoist the British flag, and though they really were proletarians holding down low-paying jobs to feed their families they did not have to follow a Marxist script. The Lower East Side might be the densest population center in the world, but its writers claimed the artistic right to withdraw into the private sphere. Poets of Di Yunge used the new freedom of America to feel their way into a new kind of poetry that valued the individual for his individuality rather than as a representative voice. This movement was so large and dynamic that by the end of World War I literary influence had reversed course and was flowing from America to the Old Country rather than from what had been its Warsaw center to the periphery.

By 1919 a new literary cohort had spun off from its predecessor, producing its own manifesto that moved farther in the same inward direction. The Yiddish Introspectivists, or Inzikhistn, maintained that all good poetry, whether private or political, filtered reality through the prism of the individual consciousness. They championed free verse on the grounds that poetry written in preexisting patterns of meter and rhyme could not, for that reason, express any unique interiority. Celia Dropkin published her work in the little magazines of this group, though it soon became clear that even authors of the Inzikh manifesto did not strictly adhere to its guidelines. In principle, American Yiddish publications had always welcomed women into their pages (Moshe Leib Halpern and Jacob Glatstein adopted female names in order to get their first poems published), but neither Dropkin nor her closest female contemporaries—Anna Margolin and Rachel Veprinski—were insiders in the poetry circles to which their lovers belonged, and their temperaments and individuality kept them from even imagining any separate women’s journal. At least partly on account of their marginality in the male atmosphere of American Yiddish literary circles, they placed femaleness or womanhood at the center of their work.

Dropkin used free verse as if in a bid for physical unshackling, yet the person in the poems seemed always to be hemming herself in emotionally, often in masochistic scenarios. The best known of her poems is “Di tsirkus dame” (pronounced DAH-meh), translated variously as “The Circus Lady,” “The Acrobat,” or “The Circus Dancer” in the translation by Grace Schulman I will be citing here, whose speaker dances among daggers stuck around the ring with the blades pointing upward. The spectators watching in fascination do not know how badly the dancer is tempted to stumble, until she declares herself in the final stanza: “I am tired of gliding around you, / cold steel daggers. / I want my blood to heat you. / I want to fall / on your naked spears.”

Which feature of this poem was the most provocative? Was it the image of the circus that was popular at the time among Yiddish as well as European writers as emblem of rude, common, or freakish entertainment? Or the daredevil exhibitionism that draws attention to risk rather than artistry? Or the erotic subtext, so pronounced that no Freudian was needed to interpret the menace of the masculine daggers? The genuinely audacious act was the poem itself. The woman who seeks the thrill of wounding herself in public risks the aggressive, injurious reactions of her viewers—who are now the poet’s readers. Whatever drives the performance, the poem certainly captures attention.

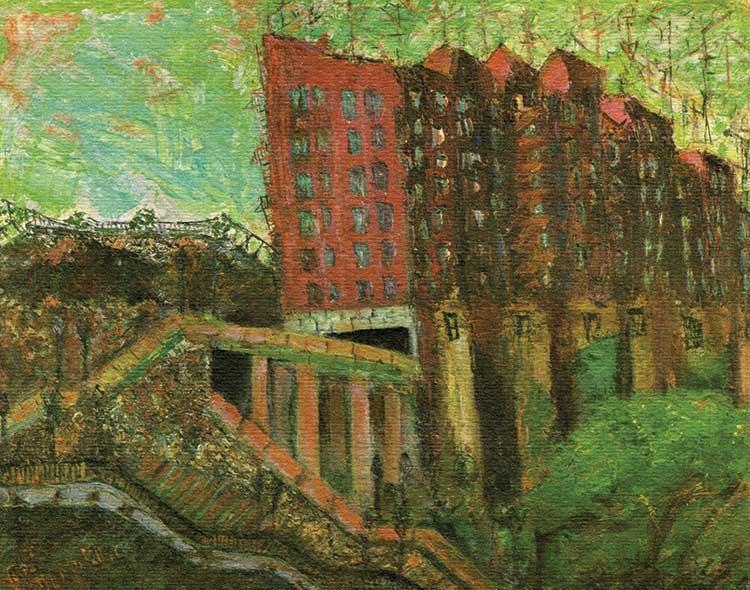

I was thrilled when the Dropkin family sent me the expanded version of Celia’s only published book, In heysn vint (In the Hot Wind), that they issued in 1959. The book also contained reproductions of paintings that the poet had done when she stopped writing poetry. But all this is merely background to the poem that got under my skin. When Irving Howe, Khone Shmeruk, and I undertook to coedit The Penguin Book of Modern Yiddish Verse, I immediately flagged it for inclusion:

Everything I say and do

you soak in the filth of your suspicion.

You mock me with cold heavy glances.

Worms slither from my fingers.

My eyes turn hideous, like those of a witch.

My hands are snakes

that uncoil to choke you;

but my feet stand shamed

glued to the floor,

trying in vain to escape

your cold mocking glances.

[Adapted from the translation of Grace Schulman]

The woman in the poem does not say what, if anything, she has done to earn her accuser’s mistrust. Although she is the poem’s subject, its tone is determined by the person who has turned her into its object. She has been humiliated—or allowed herself to be humiliated—by someone else’s disparagement and suspicion. Her experience prompts many questions: What grants that unseen person the power to change her into the object of his derision? And why does she submit to such a verdict? The phrase that kept reverberating in my head was the one in the second line that serves as the poem’s title, in koyt fun dayn fardakht. You soak me . . . not simply in dirt, which would have been shmutz, but in koyt, in the filth of your fardakht, the Germanic term for suspicion or distrust. The grating and guttural sounds of those two nouns—koyt and fardakht—neither of which I previously associated with poetry—have the power to turn the woman into an odious, hideous creature. And the verb toyvlen that the poet uses for to “soak” or “immerse” in that second line is also the word Yiddish uses for ritual immersion, the prelude for sanctified sex in one context and for baptism—as in conversion to Christianity—in the other, compounding the antagonist’s transgressive effect on the woman. Temperature is the gauge to Dropkin’s poetry: The chilling treatment the woman receives turns her ablaze with fury which makes her inability to strike back all the more vexing. Why is she unable to act on her own behalf?

As I say, the poem got under my skin but I could not say why. None of my complicated experiences in love or antagonism had ever made me feel ossified, as the woman is here. The intensity of the poem ought to lead to an explosion of feeling and instead it turns back to the cause of her infuriation—the rejection that shames her and makes her feel hateful without being able to act on her anger. I admired the poem without being able to share in its experience.

One day during a trip to Israel in 1994 a Hamas suicide bomber detonated a bus in Tel Aviv killing 22 people and wounding 50 others. A paper I was reading published a copy of the covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) and I read through the preamble’s determination to obliterate Israel and the call to every Muslim to take this on as a sacred duty. I had read such screeds before but suddenly it was too much. Unbidden, the words leapt to mind: “Vos ikh zog un tu, / alts toyvlstu in koyt fun dayn fardakht”(Everything I say and do /you soak in the filth of your suspicion.”

I rehearsed the poem again and yes, there was just what I was feeling. Your pathology transforms me into an ugly and malicious creature, glued to the floor, immobile, unable to exact revenge. It was suddenly clear to me why the woman in the poem could not act on her fury. It wasn’t because she was a masochist or enjoyed the rebuff. She cannot strike back because she wants to be accepted by the very person who will not grant her love, or in this case even the semblance of coexistence. I am inhibited from lashing out at my accusers not by fear of them but by the hope I have invested in their changing—which I realize cannot and will not happen.

That transmogrified and impotent Jew was no stranger to poetry. Heinrich Heine’s famous ballad “Princess Sabbath” depicts “Israel” as the prince whom a sorcerer has transformed into the likeness of a dog. All week long this mutt lives in the town’s filth (there’s that word again—in its German form, kot), scrounging scraps from its master’s table. Hexed by some malicious power, Israel enjoys release from doggy servility only on Sabbath, when he retreats into Jewish observance. Heine knew all about enduring the distrust of those whom you try to accommodate, having earned it by converting to Christianity, which he famously called his “ticket to European civilization.” Heine’s image of the caninized Jew greatly influenced later generations of Jewish writers and poets who tried to express how it felt to live in an atmosphere of mistrust and its poisonous consequences. He provides the explicit parable for the Jewish political condition that I discovered quite by accident in Dropkin through what some would call creative misreading.

When we teach a poem, we try to see how it has organized words and meter into a complete expression, everything integrated into itself, nothing extraneous. Robert Frost, when asked to provide a poem for an ecumenical religious site, wrote:

We dance around the ring and suppose

But the secret sits in the middle and knows.

The inviolable poem is that secret. It is not a piece of luggage to transport ideas from one place to another. I know this, and I have learned a great deal from the formalist literary critics who bear down on all aspects of the poem itself without taking into account any extraneous information. I happen to favor a different form of reading, studying the context of a poem and even the biography of the poet to get as close as possible to its intention. I want to get to the heart of the poem as it was conceived by the poet. And yet against all I try to do as a reader and teacher, this poem lodged in me and waited to slip its moorings.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

No Simple Return

“I stepped into the air.” Hilde Domin wrote, “and it carried me.”

Fathers & Sons

This summer, as the current Askhenazi chief rabbi was being investigated for corruption, and issues of religion and state dominated public debate, new Ashkenazi and Sephardi chief rabbis were elected. The process was messy, complicated, and ugly. The result? Sixty-eight votes apiece for the sons of two previous chief rabbis. What does a broken rabbinate mean for Israel?

The Burnt Pot

Response #4: “On the bottom of the pot live Jewish clichés, nostalgia, kitschiness, and an uninformed Jewish pride.”

Complicated Community: A Conversation with a Jewish Chavista

What happens to a Jewish supporter of Hugo Chavez when the revolution descends into chaos?

jclayton

A really wonderful way to respond to a poem. You avoid seeing it allegorically when you speak of its association for you. So smart! A terrific reading.