This Shall Not Be in Vain

I remember—vividly—the first night I found myself in our battalion chaplain’s office during my 2013–2014 deployment to Afghanistan. At twenty-seven years old and with six years in the Army, I was a staff officer in our plans and operations cell as the United States prepared for its first retrograde from Afghanistan, which the US Army defines as “a defensive task that involves organized movement away from the enemy.” I had nothing weighing on my conscience, no great moral dilemma. I was just mad—a clenched fist of anger in my chest. If anyone had asked me to pinpoint the source of my anger, I wouldn’t have known what to say. In fact, I was afraid that the chaplain would ask me that very question once I’d sat down in his “office”—if anything in a tent can be called an office. Instead, he offered me a seat, reached into his minifridge, pulled out a near beer, and handed it to me with a quiet smile. There were no questions. Nothing but simple acceptance.

World War II Navy chaplain rabbi Roland B. Gittelsohn described such interactions between chaplains and soldiers when he wrote:

I learned that men do not always know themselves what problem brings them to the chaplain, that sometimes, indeed, they have no well-defined problem as such. They just need some quiet place where they can feel at home, some understanding person to whom they can talk.

When I read this passage from Gittelsohn’s newly published memoir, I was immediately swept back to that moment and to the thankfulness that I felt—and still feel—to our chaplain.

As a pacifist, Rabbi Gittelsohn was an unlikely chaplain, and, in fact, he cautioned the Jewish community against calling for US entry into World War II—until Pearl Harbor. His dramatic change of heart did not happen overnight; it took eleven months of soul-searching for Gittelsohn to don the uniform of the US Navy. Like any good scholar, he laid out the reasons for his change: pride in Jewish military service, worries over the fate of Jews during the war, a desire to be there for the service members who would need the comfort of religion in the darkest of places, and last—the need to silence his conscience. “And what are you doing about all this?” he asked himself day after day once the United States entered the war. Did Gittelsohn remain a pacifist? The best he offers his readers is this statement: “Our mistake as pacifists was that we held peace up as our God and forgot that peace can come only along with the rest.”

Gittelsohn was a prolific author by the time he went to war (and far more prolific after it), so it was natural that he would write a reflection on his service in the closing days of the war. And yet, he never published it. The memoir remained hidden in his file at the American Jewish Archives in Cincinnati, Ohio, until researcher Ronit Stahl uncovered its 165 typewritten pages in 2007. Published nearly seven decades after it was first written, Pacifist to Padre is more than just a narrative of wartime service by the first Jewish Navy chaplain to serve with Marine Corps units in World War II; it is a reflection on what it is to be human involved in the inhumane task of making war on one’s fellow humans. Gittelsohn’s memoir has been published nearly as it was written. Editor Donald M. Bishop has supplied helpful annotations that provide additional information on people, places, and events that the reader encounters in the work, as well as a glossary of acronyms—always necessary to help translate the jargon of military life.

Gittelsohn’s memoir carries the reader from his first decision to join the military in 1943, through his chaplain training, to his time spent ministering to service members in various locations around the country and then to the Pacific, and finally to Iwo Jima, Japan, in 1945. It is written chronologically but reflectively. The war was scarcely over by the time he had written it, and the memories still feel raw and authentic.

One would think that a memoir of a wartime chaplain by a rabbi who served with the Marines in the Pacific would deal mainly with combat, conscience, and matters of religious significance. But at the outset, Gittelsohn tells us that “this is not a war book.” While Gittelsohn does write about combat and the suffering it brings, often in great detail, he is surprisingly focused on life. When these young men in the most difficult of life circumstances had no one else to turn to, there was the chaplain. Much of the book is devoted to vignettes about working with young marines to help improve their lives and show that they were not alone.

Gittelsohn writes of getting to know a seventeen-year-old Navy medic nicknamed “Junior” while in training. The night before the young man was to ship out to the Pacific, Gittelsohn met with him and several other young men. The talk turned suddenly to prayer, and Junior asked, “Suppose a fellow feels that he wants to pray, but he’s never prayed before by himself, and . . . well . . . after all . . . I’m not a chaplain, so what should I do?” Gittelsohn explained that personal prayer was merely a conversation, that whatever he said would be more than acceptable. That seemed to be enough for Junior, but as the group broke up, he pulled Gittelsohn aside and said, “There’s one thing I want you to know, Chaplain. It isn’t for myself I want to pray. I realize how much those guys out there on the islands depend on us. I want to pray that I won’t crack up when they need me. I want to pray that I’ll be able to use all the things they’ve taught me here to save lives, without getting too scared.” Those words remained with Gittelsohn far after the young man had gone on to whatever fate awaited him in the South Pacific. They seemed to burn into his soul:

When a youngster of 17 years can face Japanese snipers with that kind of prayer on his lips, he has come pretty close to the rock bottom that counts most in life. How many of us, who are several times 17 years, can say that the holiest hope in our hearts is: “I want to pray that I don’t crack up when they need me.”

Loneliness goes hand in hand with military service. Torn from the support structures of life, friends, and family, service members are thrown into situations that test their ability to overcome this feeling. From the first night of basic training when you lie there, shivering, thinking about the decisions that led you to this point, to the loneliness of guard duty, outpost duty, or any of the other innumerable duties that leave your mind free to wander. And then to the grave loneliness of danger in a foreign land, or the loneliness of command. Loneliness can lead to despair. And there, as Gittelsohn writes, is where “the chaplain’s first gift of making morale is just being a good friend.”

At its heart, Gittelsohn’s memoir is an ode to the humanity of those who make up the military services. His memoir is a litany of moments in which kindness, understanding, and encouragement turned marines from despair to hope, from loneliness to belonging. In the midst of a vast and necessary war machine, Gittelsohn emphasized that it was the chaplain’s duty to restore the service member’s humanity in the face of both the war and the bureaucracy of the military:

We can help the victim of red tape to see himself as a part of the much larger picture and to realize that in an undertaking so utterly, immeasurably vast, some amount of confusion is simply inevitable. The boy who can perceive that—even though he is actually in no better position than he was before—is apt to feel at least that the integrity of his own personality has been somewhat restored.

But finding one’s humanity in war is a formidable proposition. Here, Gittelsohn drives directly to the heart of the matter: that it all must be worth something. When describing a conversation with a young Navy corpsman, he writes with powerful religious feeling that “no man alone really has a soul, that each one really has a small part of a greater soul, that no one of us is any good unless his little piece of soul is together with the rest.” It’s a sentence I found myself returning to again and again.

Gittelsohn saw that a soldier may see the need for sacrifice on the battlefield and act, but that for a person’s soul, there must be something more: “Then we need a picture of the new world, and a grim determination that we can and will achieve it.” Gittelsohn saw the great purpose of the war as more than just a fight against totalitarianism; it was, in essence, to fulfill the words of the Declaration of Independence, that “all men are created equal.” He describes a pharmacist’s mate:

He would use a lesson on the administration of blood plasma to point out the essential equality of all races, religions, colors, creeds and bloods. Or in speaking of some great scientific discovery, he would go out of his way to emphasize how the various immigrant groups that came to America have contributed to the sum of its culture, both in science and in the arts.

It is Gittelsohn’s frank self-awareness and candor that make his memoir so exceptional. He chides his readers toward the middle of the book for expecting a work on religion in uniform. “Religion is a part of life,” he tells us, “not apart from life.” He lived alongside his marines through the Battle of Iwo Jima. Japan was using that tiny, remote island to launch aircraft assaults on US forces in the Pacific. If the island could be taken, US B-29 bombers could launch from there to drop their payloads on the home islands of Japan.

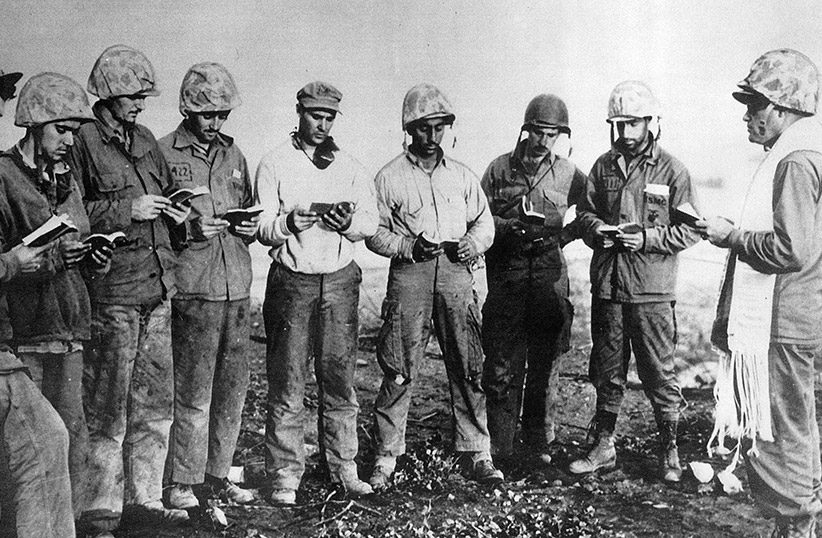

The US assault began on February 19, 1945. Nearly seventy thousand marines fought on Iwo, and nearly seven thousand of them made the ultimate sacrifice. Gittelsohn was there, praying with them on the blasted black volcanic sands, living with them through the thirty-five days of desperate combat, and, ultimately, standing at many gravesides. “It is not good, at one and the same time, to want to do so much, yet be able to do less than little,” he writes of these brutal weeks.

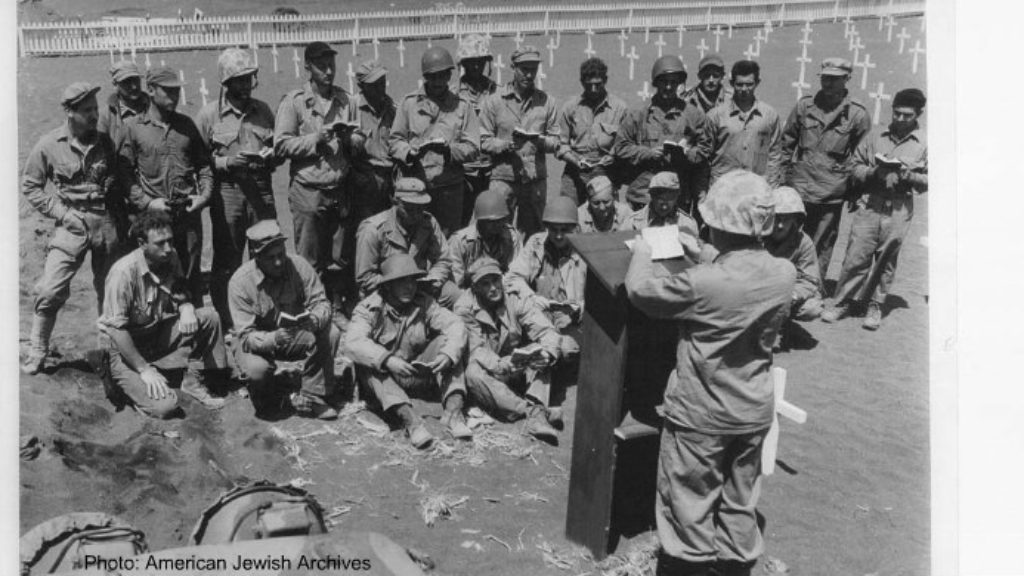

Japan and the Axis powers were not the only enemies Gittelsohn faced. In addition to the loneliness all soldiers confront, he faced anger and prejudice from within the ranks. We would like to believe that with the nation fighting the evil of Nazi Germany, antisemitism would have already been conquered in the US military. Yet, when his senior chaplain asked Gittelsohn to give the memorial sermon at the service for all the fallen marines on Iwo Jima, several Protestant and Catholic chaplains vociferously objected to a Jew speaking over the graves of Christian dead. Gittelsohn writes:

I do not remember anything in my life that made me so painfully heartsick. We had just come through nearly five weeks of miserable hell. Some of us had tried to serve men of all faiths and of no faith, without making denomination or affiliation a prerequisite for help. Protestants, Catholics, and Jews had lived together, fought together, died together, and now lay buried together. But we the living could not unite to pray together!

Gittelsohn delivered his remarks instead to a small group, including three Protestant chaplains, gathered at the Jewish section of the Fifth Marine Division cemetery under the shadow of Mount Suribachi. In a moving eulogy that evoked Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Gittelsohn vowed that the dead would not have died in vain and called for an end to racism, to wage exploitation, to war profiteering, and to isolationism. But most of all, he appealed to us—the living—to make the sacrifices of war mean something:

Whoever of us lifts his hand in hate against a brother, or thinks himself superior to those who happen to be in the minority, makes of this ceremony and the bloody sacrifice it commemorates, an empty, hollow mockery. To this, then, as our solemn, sacred duty, do we the living now dedicate ourselves—to the right of Protestants, Catholics, and Jews, of white men and negroes alike, to enjoy the democracy for which all of them have here paid the price. . . . Thus, do we memorialize those who, having ceased living with us, now live within us. Thus, do we consecrate ourselves the living to carry on the struggle they began. Too much blood has gone into this soil for us to let it lie barren. Too much pain and heartache have fertilized the earth on which we stand. We here solemnly swear: this shall not be in vain! Out of this, and from the suffering and sorrow of those who mourn this, will come—we promise—the birth of a new freedom for the sons of men everywhere.

War brings death, sadness, and sorrow—and with it, a search for meaning. I see it in my own generation of officers who have served their country during the last twenty years of wars in the Middle East and Asia. We search desperately for a meaning that exceeds politics. If humans must die—and kill—they want, we want, the meaning of it to transcend mere existence.

I read Gittelsohn’s memoir after the fall of Kabul, Afghanistan, in 2021 with a feeling of emptiness as I asked, “What was it all for?” I felt as if he were reaching through the pages, telling me that I was asking the wrong question. He was asking me what I was doing to make the world a better place: “What are you doing about all this?” Why wasn’t I working to achieve a better world in the name of those who cannot experience it anymore? “Spend the rest of your days achieving justice and fulfillment for him,” Gittelsohn writes of the fallen soldier. And then the soldier lives on.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Getting Along with the Gentiles

From the Brandeis Book Stall to the sands of Iwo Jima (and halakhic flexibility).

Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh Walk into a Bar: Passover in the Union Army

Yankee ingenuity at Passover: how one regiment made a Seder in the midst of the Civil War.

Pancho Villa and the Star of David Men

When the Young Men's Christian Association began offering wholesome recreation to soldiers in 1916, Jewish leaders were as as worried about evangelism as they were about bars and bordellos.

A Cedar of Lebanon

In addition to the weight survivors feel, Friedman bears the burden of giving voice to the place that shaped young men’s lives and took others, while leaving no official trace.

Rabbi Dov Peretz Elkins

What is the title of Rabbi Gittelsohn's memoir book?