Pancho Villa and the Star of David Men

In March of 1916, the still slightly infamous revolutionary general and politico Francisco “Pancho” Villa, angry at the United States for supporting his rival for the Mexican presidency, led an assault on Columbus, New Mexico, killing 23 Americans, including soldiers of the 13th US Calvary. Properly outraged, President Woodrow Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing to Mexico to capture or kill Villa, but he never did. Jessica Cooperman’s fine new book about World War I and American Jewry begins with Pershing’s unsuccessful Mexican campaign because it set the stage for the larger story she has to tell. Among the ten thousand Regular Army troops and the hundred thousand National Guardsmen who participated in the “Punitive Expedition,” there were approximately 3,500 Jews. The American Jewish community’s efforts to look after them established a precedent for the much larger project of supporting American Jewish soldiers during World War I.

Encouraged by the War Department, the Young Men’s Christian Association had stepped in to protect Pershing’s men from what many perceived to be a greater menace than Pancho Villa: red-light districts in the border towns. The Knights of Columbus promptly sent men to the scene to provide Catholic soldiers with more congenial assistance than they were likely to receive from a Protestant organization. So did the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, which established a branch near the Mexican border where Jewish soldiers could seek “recreation without temptation.” Jewish leaders (like the Catholics) were almost as fearful of young recruits being lured to join the Protestant majority as they were of them succumbing to the bad influence of bars and bordellos. But more planning would be needed to provide Jews with the same level of services as the Young Men’s Christian Association was already making available for Protestants.

The (Reform) Central Conference of American Rabbis took responsibility for High Holiday services (attended, on occasion, by more curious or idle Gentiles than Jews), but the YMHA had only “limited success in instituting morally uplifting programs for Jewish soldiers on the Mexican border.” The Gentiles, in the opinion of the War Department, didn’t in the end do much better, but this didn’t lead to the conclusion that pastoral work wasn’t worthwhile. The lesson learned from the Mexican experience was that a greater effort would have to be made during World War I to surround soldiers with “clean and wholesome influences.” In 1917, this became the task of a new government agency: the Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA).

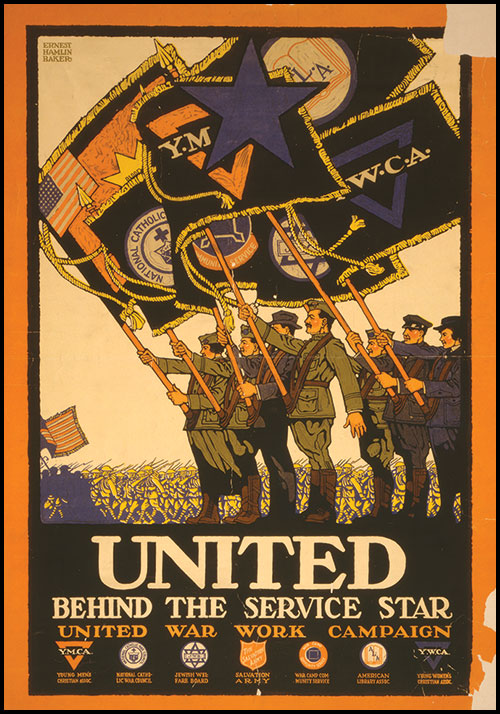

organizations into one large funding drive, November 1918. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and

Photographs Division.)

American Jews were eager to do their part for the troops, but they had to work hard to persuade the authorities that they could or should. “[W]ithin days of the United States’ declaration of war, the War Department recognized the YMCA as a partner to the CTCA,” assuming that it “would be the only civilian agency necessary to the CTCA’s program for building military morals and morale.” In effect, Protestant Christianity was to be the de facto religion of the American serviceman. Both Catholics and Jews were outraged, but Catholics, who constituted 17 percent of the American population and were expected to furnish as much as a third of the American Expeditionary Forces, had demographics on their side. Their demands for a representative on the commission could “not be ignored without jeopardizing their support for the draft and the war.” American Jews didn’t have that kind of leverage.

Shortly after the United States entered the war, a small group of prominent Jews led by Cyrus Adler, the acting president of the Jewish Theological Seminary, formed a broad-based organization to unify “Jewish efforts in connection with welfare work among military personnel” called the Jewish Welfare Board (JWB). They were largely ignored by the commission until they were able to call attention to the emergence of a socialist rival, the People’s League for Jewish Soldiers of America. This seems to have convinced the government that the JWB was its necessary partner (but not, however, to give it a seat on the CTCA). Including “the JWB alongside the YMCA and the Knights of Columbus in the War Department’s program for soldiers’ welfare work” and thereby “granting nonsectarian status to Jews and Catholics represented,” in Cooperman’s opinion, “a significant shift in the structure of American definitions of religion.”

Jewish Welfare Board, April 1919, Paris, France. (Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives.)

But that did not necessarily mean a shift toward defining religion the same way the Jews did. Consider the question of kashrut, which was a major issue at a time when considerable numbers of Orthodox Jews were being conscripted. Should the JWB be lobbying for the supply of kosher food at army bases? The Orthodox representatives on the JWB thought so. At a JWB Executive Committee meeting a few weeks into the war, Rabbi Bernard Drachman argued that the government should “supply kosher food to Jewish soldiers, as is being done in Austria.” Dr. Adler was, of course, more moderate, suggesting “that if the government could not do so, this Board could undertake the matter of supplying kosher food wherever it was requested at its own expense, provided that a specific fund was raised for this purpose.” Reform members of the board objected to the idea of catering to mainly Orthodox concerns “‘and goluth [diaspora] sentiments,’ rather than the actual needs of American Jewish servicemen.”

Knowing that kosher food was a lot to ask for, the board raised the issue with the government gingerly, prefacing its request with the statement that Jewish legal authorities had long ago made it clear that “religious laws may be set aside in the defense of one’s country.” This was too meek for many in the Orthodox community, but too much for soldiers like a certain Captain Horowitz, who argued, among other things, that “[t]he prescribed ration is wholesome as well as sufficient; the prescribed components have been determined with scientific accuracy to balance the whole; we cannot in reason insist on the ‘kashrith.’” This was also the opinion of the higher-ups in the War Department, who had the decisive say in the matter.

Even if the JWB couldn’t help Jewish soldiers keep kosher, it could provide the kind of activities that the YMCA provided: lectures, movies, and dances (with the right sort of women). And it could reinforce the patriotic message by stressing “that through engaged adherence to the tenets of Judaism, Jews could become better citizens and better Americans.” One of the most important actions it took to foster such adherence was to lobby successfully for the appointment (for the first time since the Civil War) of Jewish military chaplains to serve in the US Army.

Once the necessary legislation had been passed, the JWB assumed responsibility for selecting the men who would fill the limited number of positions that had been created. The board made reasonable efforts to select a denominationally diverse crew of rabbis, but the criteria imposed by the government and endorsed by the board itself effectively ruled out anyone who lacked a good secular education, and thereby excluded practically all of the available Orthodox rabbis. The vast majority of the 25 candidates who were eventually approved were graduates of the Reform Hebrew Union College.

Since a couple of dozen chaplains obviously couldn’t handle the job of providing religious services for tens of thousands of soldiers, the board hired an additional 30 or so “camp rabbis”—usually rabbis from communities near military bases—as well as hundreds of more- or less-qualified field workers, who became known as “Star of David men.” Together, they “led the majority of religious and social services provided by the JWB.”

As part of its effort to direct the work of its cadres, the board produced a magazine, the Welfare Board Sentinel, for distribution in military camps. Its very first issue contained a “Decalogue for Jewish Soldiers,” written by Rabbi William Rosenau. The first commandment read “I am America, thy country, which brought thee out of bondage to liberty”; its fourth prohibited taking the name of America in vain; and its fifth was to honor “thy Superior Officers.” Cooperman may go too far when she maintains that this strange piece of overzealous rhetoric actually displaced “God and sacred texts,” in Rabbi Rosenau’s eyes, “as the ultimate source of freedom and righteous behavior,” but it certainly placed patriotism on a dangerously high pedestal. She doesn’t go too far, though, when she observes that the “first commandments surely spoke to concerns about the 18 percent of all American soldiers—and possibly as many as one-third of all Jewish soldiers—born in other countries.”

One man who took this sort of thing very seriously without substituting America for God was a young Reform rabbi named Elkan Voorsanger. The son of a prominent San Francisco rabbi, Voorsanger was serving as an assistant rabbi in St. Louis when the United States entered the war. He immediately gave up his clergy deferment to fight in a war that he didn’t support and went to France as an enlisted man. Voorsanger did so out of solidarity with his peers, and because he had “a country and that country is the United States,” which was engaged, he could at least hope, in a struggle “for democracy and against autocracy” that would end all war. After Congress authorized the appointment of Jewish chaplains, he became the first to receive a commission, but that didn’t take him away from the front lines. The man who became known as the “Fighting Rabbi” was described in an article published after the war as

a figure of powerful physique, forceful personality, military bearing and yet, in his intercourse with the men, one of a dominant spirituality, calling forth an evident response wherever a kindred feeling was innermost hidden—that was the figure, in the sand-colored Ford, which rode up the lines where shells whizzed most often and made its owner known and loved by every doughboy in the vicinity.

Voorsanger won a French Croix de Guerre and a Purple Heart and became the JWB’s poster boy, but he wasn’t by any means typical.

What was the impact of the JWB’s work on more ordinary Jewish soldiers? Cooperman gives us a chapter full of complaints. Orthodox soldiers, their parents, and their rabbis grumbled “that JWB workers lacked the experience to lead even Reform services and had ‘insufficient knowledge of Hebrew to conduct orthodox service.’” Reform Jews, including a young recruit named Jacob Rader Marcus, who ultimately became the leading American Jewish historian of his day, complained that the prayer book patched together by the JWB was incoherent, and that the JWB’s attempt to “legislate Judaism” left everyone dissatisfied. Zionists complained that the assimilationist JWB “cancelled everything that was genuinely Jewish from its program,” and the socialist-leaning Forverts complained that the soldiers had “no Yiddish books to read . . . no Yiddish entertainments, theatrical performances, concerts and the like.” Eastern European Jews, in general, as Cooperman puts it, “feared that the JWB was working against the real interests and needs of Jewish soldiers, which they understood as based on cultural distinctiveness rather than shared American identity.”

Nothing would substantiate their fears as much as the JWB’s position with regard to the “welfare huts,” which were supposed to serve as the headquarters for its workers’ activities, as well as their homes. Partly for the sake of convenience, but more for ideological reasons, the JWB preferred sharing space with the YMCA to having huts of its own. Religious distinctiveness was fine, but “the prospect of separate Jewish soldiers’ welfare huts threatened to cross the line from drawing strength and pride from one’s tradition to outright advocacy of segregation.”The JWB was strenuously opposed to what some of its leaders decried as “Yiddishisation” and a return to the “ghetto.”

However, sharing space with the YMCA had its problems. There were many complaints that “the YMCA used its huts not in the interest of religious pluralism but in order to pursue its evangelical work.” And this may have been the least of it. Here’s the not untypical complaint of a soldier at Camp Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts:

At one of the large YMCA hall[s] there are seated about 100 Jewish soldiers with prayer books in their hands. Along the sides of the room, Gentile soldiers are writing letters, smoking, chewing and conversing among themselves. Behind the Jews there are seated or standing several hundred other Gentile soldiers who are either exchanging stories, smoking or staring in wild-eyed wonder at the strange sight of a Jew leading the prayer as he stands with a shawl thrown over his shoulders. Many snicker and grin, as they hear a Hebrew word, or as they see the Jews rise and sit again and again. In this environment a Jewish soldier is expected to say Kaddish!!! And to crown all of this, a moving picture show is always scheduled to take place in the same hall just as soon as the Jewish services are ended.

Young Jacob Marcus, who knew the overall situation quite well, proclaimed in print, “You must build Jewish shacks because the men in the ranks want them.”

The JWB leadership eventually bowed to this pressure. It sought and received government permission to erect 51 buildings in training camps across the country. Happily, the government agreed to pay for light and heat in these structures, just as it did for the YMCA. To advertise its success to the Jewish public, the JWB produced a poster displaying a “homey JWB building filled with soldiers in uniform,” some listening to a piano played by a young woman and others studying a text. The poster “announced in Yiddish, ‘Mir haben fur ze a heim geboit’ (We have built them a home).” This was clearly a deviation from the board’s previous policy, but it wasn’t really self-ghettoization. It just added a splash of ethnicity to the religious pluralism that the JWB had sought to foster from the beginning. The idea of a “tri-faith” America did not become part of the American civic consensus until after World War II, when it was popularized by the Jewish thinker Will Herberg, but, as Cooperman shows, it began much earlier. The “battle for American religious pluralism was waged by the Jewish Welfare Board during World War I,” she writes, “and against unlikely odds, the JWB won.”

Suggested Reading

Rallying Round the Flags

Derek Penslar's new book returns to aim Jewish soldiers of the diaspora to their rightful place in Jewish history.

From the Great War to the Cold War

The facts of Hans Kohn’s life are so extraordinary that it almost seems as if the first half of one remarkable figure’s biography had been spliced together with another’s in the second part.

Ritchie’s Boys and the Men from Zion

Our appreciation for stories of Jewish bravery during World War II sometimes obscures the fact that as a group Jews were powerless, reduced to begging others for a chance to bear arms.

Counting Jews

Tim Grady makes a careful but controversial case about the way Jews contributed to or supported Germany's worst excesses in World War I.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In