“Whoever Is Hungry, Come and Eat”? From the Babylonian Poor to the Ashkenazi Elijah

Passover is not only the holiday of historical memory, when Jews recount the Exodus. It is itself an artifact of Jewish history, bearing the marks of gradual development and sudden innovation. Like wine spills that stain used haggadahs, Jewish communities across the generations have left their imprint on the Passover Seder. The results can be messy but also fascinating.

Many features of the Seder as we now recognize it originated with the local habits of rabbis living in late antique Roman Palestine. Faced with the task of reinventing the Passover celebration in the absence of the Jerusalem Temple and the paschal sacrifice offered there, the sages designed the festival dinner as if it were a Greek symposium or Roman convivium, a long-running conversation over many courses and wine servings taken while comfortably reclining on couches.

The distinctly Greco-Roman quality of the rabbinic Seder, as well as the later elements added to it over time, has meant that the holiday meal struck Jews of later periods as unusual. The last of the four questions in the modern haggadah is “why on this night do we recline?” But the earliest version of the text didn’t even ask this question, because reclining while eating wasn’t unusual in Roman Palestine. Indeed, it was not until the twentieth century that scholars fully rediscovered the connection between the Greek symposium and the rabbinic Seder. Similarly, the Seder’s strange lexicon—terms like karpas and Afikomen—were comprehensible loanwords in the Rabbis’ Greco-Roman context, though they have sounded odd to later, non-Greek-speaking Jews.

Other aspects of the haggadah remain baffling, even today. Take the famous first lines with which the central maggid section of the Seder begins:

This is the bread of affliction that our forebears ate in the land of Egypt.

Whoever is hungry, let him come and eat; whoever is in need, let him come and perform the Passover (kol dikhfin yetei veyekhol; kol ditzrikh yetei veyifsakh).

To whom is this invitation addressed? The guests are, after all, already crowded around the table. And why is the invitation issued in Aramaic rather than the classical Hebrew of the rest of the haggadah? Finally, why isn’t this line mentioned anywhere in rabbinic literature? The rabbinic reinvention of Passover as a holiday of historical memory happens here, in the maggidsection, where the story of the Exodus is told and discussed, and yet its resonant opening lines were apparently unknown to the rabbis of the Mishnah and Talmud.

This was already a puzzle in the Middle Ages. The thirteenth-century Italian commentator Isaiah di Trani explained that the hungry are invited because eating matza on Passover is an obligation incumbent on everyone, including the needy. But this begs the question: Why should a host invite guests who are already comfortably seated inside his home? Another unsatisfying medieval suggestion is that the overture is directed at the ravenous Seder guests as they await the matza, which will be served only much later in the evening, at the very end of the maggid section. This hunger is familiar to many Seder-goers, but what purpose is there in officially mentioning it in the haggadah text? Moreover, just because one is hungry in the moment doesn’t make one needy, as the text seems to suggest. In an act of exegetical desperation, some writers have suggested that the haggadah’s unusual invitation is intended to elicit questions from the children. This is certainly a feature of the rabbinic Seder, but to use that as an answer here amounts to admitting that there simply is no compelling explanation.

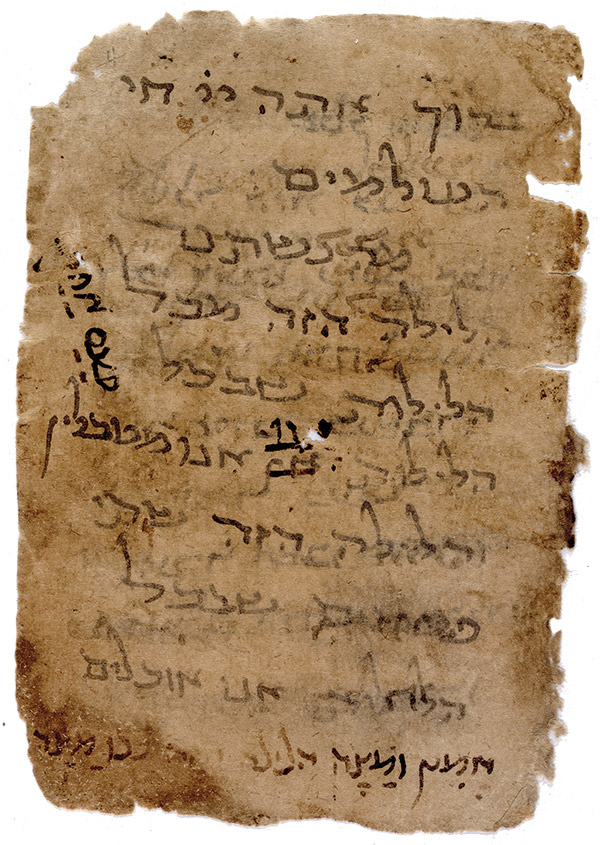

Notably, the Seder’s opening invitation first appears in Babylonian haggadahs from the ninth century and is missing from the few surviving haggadahs that preserve the old Palestinian rite. I began hunting for Babylonian antecedents and was surprised to discover a close parallel between the haggadah’s “whoever is hungry” passage and a story in the Talmud with no connection to Passover. There we read of a wealthy Babylonian rabbi named Rav Huna, who, before beginning a meal, “would open the door and say: ‘whoever is in need, let him come and enter’” (b. Taanit 20b-21a). Another story, preserved in some early Talmudic manuscripts, extolls the generosity of a Babylonian sage for regularly “putting out baskets of bread and dates and saying: ‘whoever is hungry, let him come and eat’” (b. Berakhot 58b).

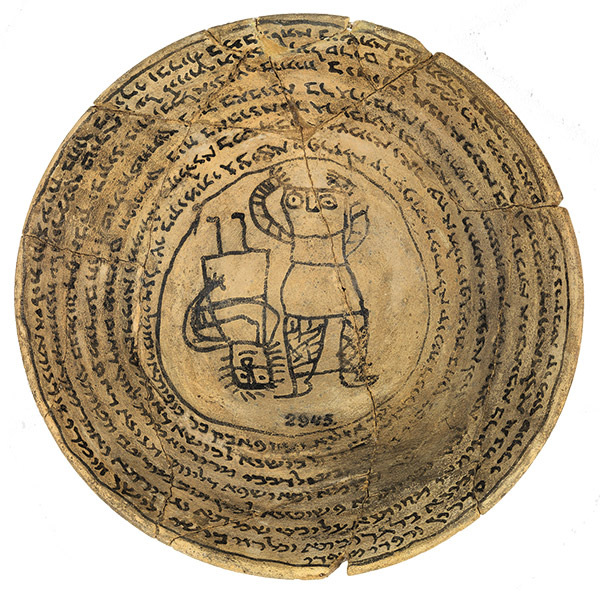

I soon found another echo of the invitation formula in some of the Aramaic incantation bowls, a fascinating collection of artifacts produced in late antique Babylonia. Inscribed with incantations that spiral out from the bowls’ centers, they were used as amulets to protect their owners’ homes from demons, witches, and other things that go bump in the night. One incantation describes a magical ruse in which a homeowner climbs up to the roof to issue a passive-aggressive invitation at threatening forces:

I, Min-malka daughter of Immay, went up to the roof and said to them “Why have you come, O evil sorceries and upsetting mysteries? If you are hungry, enter, eat, eat! If you are thirsty, enter, enter, drink! If you are dry, enter, be anointed. If you are not hungry, and if you are not thirsty, and if you are not dry, remove yourselves and get out from them.”

Here, the generosity of the invitation is conditional: the malevolent forces are invited to enter only if they agree to forgo their evil intentions. That is why Min-malka is shown making the invitation while standing on the roof; the door must remain closed until the condition is accepted. Still, the ritual logic of this incantation is that an overt act of generosity has the power to disarm evil.

The appearance of these invitations in two late antique Babylonian sources confirms the hunch that the haggadah’s similarly phrased opening overture was coined in Babylonia. This answers the question of why it is in Aramaic, the language spoken by Babylonian Jews, but not why it is in the haggadah.

The solution, I believe, can be found in a teshuvah, or legal responsum, that is attributed to Rav Matityah, a head of the Babylonian rabbinic academy of Pumbedita who lived in the ninth century:

Regarding this practice of saying “Whoever is hungry, let him come and eat”: Such was the custom of the Fathers (minhag avoteinu). They would remove their tables and not close their doors, and they would say this in order that their poor Jewish neighbors would come to eat, and they would receive reward for doing so.

According to Rav Matityah, the Seder invitation was not mere lip service, and it came with real expectations and obligations. It was spoken in Aramaic, the common vernacular, so the poor and the hungry outside could understand it; the doors to the house were kept open so that they could hear the invitation and actually enter; and the overture took place just before the beginning of the meal.

Although Rav Matityah does not explain why earlier generations introduced

this invitation to the Passover Seder, it must have been another instance of

Jewish communities adding their own ritual twist to the festival meal. One of

the core components of the haggadah, the obligation for participants to playact

the redemption of the ancient Israelites from slavery to freedom and poverty to

wealth, is already mandated in the Mishnah. Among rabbis in the Land of Israel,

the manner in which the dramatic transition was enacted was based on the

culturally prevalent forms of elite banqueting in

Roman Palestine. In Babylonia, on the other hand, the Mishnah’s mandate was

realized through the overt generosity that was already characteristic of

wealthy Babylonians: the door was opened, and the poor were formally invited in

to dinner.

Rav Matityah continues the teshuvah by reporting that the practice of issuing a late-breaking Seder invitation began at a time when Jews lived in predominantly Jewish neighborhoods. However, as the neighborhoods became more mixed, new efforts had to be made to provide communal support for the poor before the beginning of the holiday, so that needy Jews wouldn’t have to wander the streets of increasingly non-Jewish communities in search of last-minute Seder hosts. Although already in his day actually inviting the poor to one’s Seder with the “whoever is hungry” formula was no longer practiced, Rav Matityah informs his questioner and readers that he continued to keep the “custom of his fathers” by opening the door and issuing the invitation, even though there were no longer poor people outside the door to accept it. The fact that some Babylonian-influenced haggadahs from the same period do not include the invitation may suggest that some chose to abandon it altogether. But Rav Matityah’s practice would win the day.

In time, as elements of the invitation became further ritualized and their original context forgotten, new explanations, as well as new practices, developed. An eleventh-century North African rabbi named Nissim b. Yaaqov provides the earliest evidence that the custom of opening doors had migrated from Babylonia and become disconnected from the original invitation and treated as a distinct ritual act. Tapping into the old rabbinic idea that Passover eve was destined to be the date of future, and not only the past, redemption, Rabbi Nissim explained that on Passover night, “the doors of the house remain open, so that when Elijah comes we will go out to greet him speedily, without delay.”

The disconnect between the original practice and later ritual is even more apparent in the explanation offered by the twelfth-century Provençal rabbi, Abraham ben Nathan HaYarkhi. According to him, to express the hope of redemption on Passover evening, it was no longer the doors of the house that had to be unlocked but instead the bedroom doors, so as to be prepared in case the messiah came later that night. The invitation’s original connection with the poor in the streets had been entirely lost.

Given the newfound association of opening the door with faith in the arrival of the messiah, the culmination of Jewish history, some communities relocated the act of door opening to the end of the meal, when the final cup of wine was poured. In classical rabbinic literature, the Seder’s four required cups of wine had already been linked to four different stages of salvation, with the last cup symbolizing salvation’s completion. Some medieval traditions, first attested in eleventh-century France, introduced a prayer for the speedy destruction of Israel’s enemies as part of that redemption, opening with the searing words, “Pour out your wrath upon the nations.”

Over time, the practices that had come to signify the future salvation—the opened doors and the prayer recited after pouring the final cup—merged. Ashkenazi haggadahs from the fifteenth century depict either the messiah or the messiah and his herald, the prophet Elijah, arriving at this point, toward the end of the meal. A century later, some sources describe Seder participants dressing up as Elijah, entering through the open door, and mimicking the prophet’s much anticipated arrival. Other traditions recommend fervently issuing an invitation to Elijah and the messiah: “Elijah and the messiah, enter!”

Ultimately, the link between Elijah and the conclusion of the meal led some Ashkenazi Jews to inaugurate another well-known custom, namely, the pouring of an additional glass for the prophet, the so-called kos eliyahu, or Elijah’s cup. Fascinatingly, as the invitation to join the Seder drifted further and further from its original social context, in late antique Babylonia, it regained some of its initial purpose: an open-door invitation for a guest—albeit a mythical one—to join the Seder.

Suggested Reading

Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh Walk into a Bar: Passover in the Union Army

Yankee ingenuity at Passover: how one regiment made a Seder in the midst of the Civil War.

Frogs, Griffins, and Jews Without Hats: How My Children Illuminated the Haggadah

The illustrated haggadahs of medieval Europe contain more than just rich, colorful depictions of the Exodus story. The closer you look, and with innocent eyes, the more sophisticated the artistic commentary becomes. There are drawings of rabbinic midrash and not a small amount of political satire and polemic.

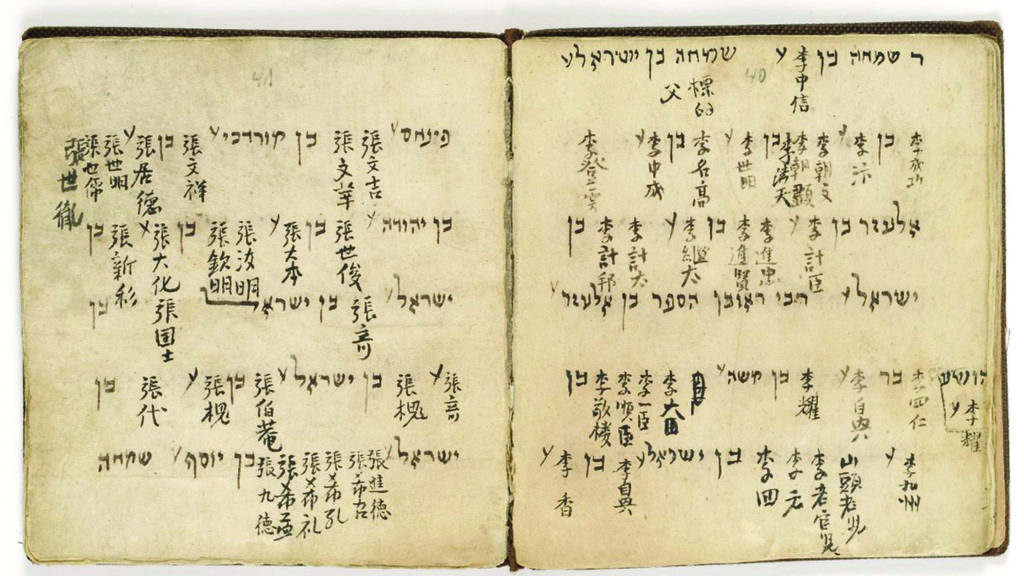

Why Is This Haggadah Different?

The Haggadah of China's Kaifeng Jews is not all that dissimilar from your Maxwell House version—but it speaks volumes about the community that produced it.

Exodus and Consciousness

Who left Egypt ? And how did the Israelites experience God? Richard Friedman is a biblical detective, James Kugel is more of a literary anthropologist.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In