Frogs, Griffins, and Jews Without Hats: How My Children Illuminated the Haggadah

About a decade ago, just before Passover, I found myself in a Conservative synagogue in Riverdale, New York, discussing the way that the magnificent 14th-century illuminated Spanish “Golden Haggadah” illustrated the plague of frogs. I was pointing out the fact that the image—which shows Aaron striking a large frog and many other, smaller frogs emerging from it—depicted not only scripture, but also a midrash found in Tanchuma and mentioned by Rashi. Since Exodus 8:2 uses the singular “the frog emerged” when describing the plague, this interpretive tradition suggested that only one frog initially came out of the Nile.

The illustration thus demonstrates a point made by Bezalel Narkiss and his students at the Center for Jewish Art in Jerusalem. Whereas previous scholars tended to view medieval Jewish art as simply illustrating scripture, Narkiss and others showed that illuminated Jewish manuscripts illustrated not only the literal biblical text, but midrash as well. This demonstrated that, regardless of whether the artists were Jewish or Gentile, their patrons were commissioning art that was not only stunningly beautiful but distinctively Jewish.

“Some versions of this midrash describe the single frog as monstrous in size and imagine the swarm of frogs as emerging from its mouth, as we see here,” I was saying, when out of the corner of my eye, I saw my then 8-year-old daughter Elisheva bouncing up and down. “Not now, Shevi!” I stage-whispered. “But, Abba,” she replied, “I noticed something in the picture!” Swallowing my annoyance, I decided to use this as ‘a teachable moment.'”

“Yes, Shevi?” “Abba, you just said that the frogs are coming out of the big frog’s mouth. But Aaron is hitting the big frog’s head, and all the little frogs are coming out of his tushy!”—at which point she collapsed in a paroxysm of laughter, and I turned beet-red. My cheeks still burn at the memory. But Shevi was absolutely right. This peculiar detail is unique among medieval haggadot, which generally show Aaron striking the Nile or striking one (not particularly big) frog on the head (as for instance, in the so-called “Brother Haggadah,” also from 14th-century Spain), without depicting the emergence of the other frogs from any of its orifices. The Passover Haggadah is based on the idea that “you shall tell your children,” (Ex. 13:8) but, with their unprejudiced eyes, my children have often ended up telling me.

Manuscripts such as the Golden Haggadah did not come cheap. They could only be dreamt of by the “one percent” of 14th-century Jewish Barcelona. Every application of pen and brush to parchment represented a considerable expenditure. Consequently, the artists were, almost certainly, very closely supervised, and the inclusion of specifics such as the precise origin of the swarm of frogs must have been considered carefully. Such pictorial details, especially the apparently odd or surprising ones, are windows into the social, intellectual, religious, and political universe of the Jews who commissioned these treasures.

What, then, do we learn from the case of the miraculous farting frog of Barcelona? The men and women who planned and executed this manuscript moved beyond the biblical text and its rabbinic commentary to articulate an angry, hilarious, and entirely contemporary bit of commentary. That commentary, much like the spraying frogs in the illustration, flies in several directions at once. It is directed, in the first place, at the historical Egyptians of the Exodus narrative. But it is also directed at contemporary oppressors of Jews. (The horrified Pharaoh looks, of course, like a medieval Christian king.) Moreover, the picture also gently mocks the elegance of the manuscript itself, where in general, nary a hair is out of place on the stately figures playing out the drama of the plague scenes.

Bezalel Narkiss once described the artistic style of the Golden Haggadah as barely distinguishable from that of contemporary Christian books of Psalms. In fact, however, what my daughter’s observation shows is that—in spite of their relative wealth and power—the patrons of this Spanish Haggadah felt vulnerable to the Pharaohs of their day and somewhat angry about their political situation. So they commissioned a manuscript containing—among many learned and sophisticated visual commentaries—this grotesque little detail. Hidden in plain sight, it is certainly playful, but it was also a scatological revenge fantasy.

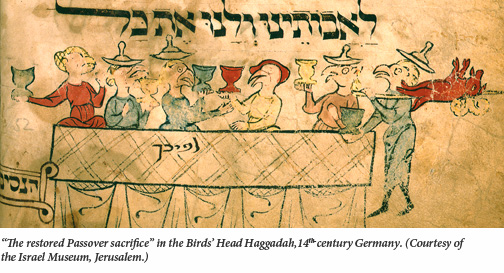

The Golden Haggadah’s miraculous frog is a small detail, liable to be glossed over in a manuscript that contains many treasures. But no one could fail to notice the animal-headed figures in the first, and most famous, illuminated Haggadah, the so-called “Birds’ Head Haggadah.” Within the rather modest field of Jewish art history, the Birds’ Head Haggadah, produced in Southern Germany around the turn of the 14th century, is as much of an enigma as the Pyramids of Giza or Mona Lisa’s smile. It mysteriously depicts all of the Jews in its pages as having the heads of birds. However, their beaks are supplemented with mammalian ears and beards so that they look like griffins (hybrids of lions and eagles). With their human bodies, these lion-eagle-human hybrids recall the kruvim, the “cherubs,” on the Ark of the Covenant.

As Meyer Schapiro and others have noted, these figures are clearly an attempt to comply with the halakhic prohibition against complete pictorial representations of humans. But this can’t be the whole answer, for the Birds’ Head Haggadah complies with this prohibition in the case of Pharaoh and his soldiers by representing them (originally) with blank, human-shaped faces. This may be a case of artistic aggression (as enemies of the Jews, the Egyptians are literally effaced) but it also shows that one can avoid depicting the human face without resorting to birds’ heads.

One could read the artistic choice of the Birds’ Head Haggadah as deliberate and political. Following this interpretation, these griffin-like figures combine the Lion of Judah with the Imperial eagle, since the Jews were regarded as servi camerae regis (servants of the royal chamber) in the Holy Roman Empire. One could also understand the figures mystically: Lions, eagles, and humans recall three of the four creatures Ezekiel describes as bearing the Divine Chariot (the fourth creature, the ox, being excluded since it recalls the sin of the Golden Calf). However, since it is impossible to know the political inclinations, or mystical sophistication, of the artists and patrons of the manuscript, my own speculation is that these figures may derive in part from the much more widely known and accessible saying of Pirkei Avot:

Judah ben Tema used to say “be strong as the leopard, swift as the eagle, fleet as the gazelle, and brave as the lion to the will of your Father in heaven.”

One can see this formula reduced to just lions and eagles in the memorial prayer Av Ha-rachamim, perhaps the most famous supplication of medieval German Jewry, which describes the Jewish martyrs of the First Crusade as having been “swifter than eagles and bolder than lions” to do the will of God. Thus, the griffin-headed Jews of the Birds’ Head Haggadah seem to reveal something of the spiritual self-perception and aspirations of medieval Ashkenazic Jews.

However, what is most interesting to me in the Birds’ Head Haggadah is what we can learn from the distinctions made among the various griffin-headed Jewish figures in the manuscript. Most of the Jewish adult male figures in the manuscript wear the peculiar, pointed Judenhut. This “Jewish hat”—of which not a single physical example survived the Middle Ages—always signifies a Jew in medieval Christian art, whether that person is a prophet, or patriarch, or an enemy of Jesus. Occasionally, it even appears on the head of Jesus himself, as in the depiction of the Supper at Emmaus in the so-called Psalter of St. Louis.

In the Birds’ Head Haggadah, almost all adult male Jews, including Abraham, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, the Israelite elders, and the leader of the Seder, are depicted as wearing the Judenhut. But there are three instances in which individuals with griffin heads are shown bareheaded. The first two are pictures of Joseph and the Israelite slaves. Rabbinic tradition is very careful to represent Joseph as remaining a tzaddik—a Jewish saint—even while working for Pharaoh. Similarly, the Israelites are understood to have remained uncompromisingly traditional, even while enslaved in Egypt—refusing to change their language, their clothing, or their Hebrew names. Given that the midrash explicitly affirms that the Jews continued to wear their distinctive clothing, the denial of the Jewish hat to these figures seems strange.

In fact, I believe this depiction to be a deliberate critique of the rabbinic tradition growing out of the actual experience of medieval Jews in Ashkenaz. One figure of medieval Jewish life was the Jew who worked in the royal court, or for local princelings, in some capacity. Although these individuals often played a key role in the safety and well being of their communities, their everyday lives at court placed inevitable strains on religious observance, as well as raising suspicions among fellow Jews regarding their true loyalties. I suspect that the image of Joseph and the slaves as Jews without hats is evidence of a real-world skepticism that, rabbinic assurances notwithstanding, Jews could ever have remained fully observant at court.

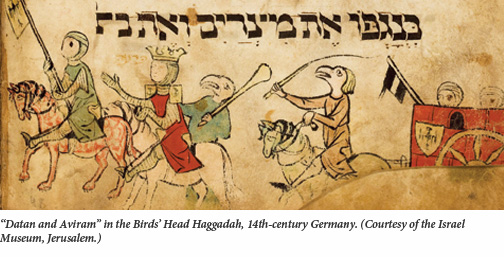

The third instance of hatless griffin-headed Jews is one I would have missed if it weren’t for another one of my children. When he was about 10, my son Misha and I were looking at the elegant 1965 facsimile of the Birds’ Head Haggadah. Seeing that Pharaoh and his soldiers, who are shown pursuing the departing Israelites, are depicted with blank human heads, he remarked that “all the mitzrim (Egyptians) have normal faces, and all the Bnei Yisrael (Jews) have birds’ faces.” Smug, in what I supposed was my superior art-historical expertise, I replied, “Look again, Misha—and this time more carefully—do all the mitzrim really have normal faces? Can you spot the two who don’t?” The child did not miss a beat. “Abba,” he burst out, “anybody can tell that those guys are Datan and Aviram!” In response to my puzzled look, he explained, “The nogshim (Jewish taskmasters)! See? One of them has a whip and the other has a club, so they have to be Datan and Aviram!”

Nogshim indeed. To paraphrase Psalms, out of the mouths of day school children wisdom is established. No previous scholar, to my knowledge, had distinguished between the figures in question and the Egyptians around them. They had assumed that, because these figures ride alongside Pharaoh and the Egyptians they must be Egyptians, and thus that the artists of the Birds’ Head Haggadah were not completely consistent. But Misha was clearly on to something.

By placing obviously Jewish figures in the Egyptian camp, the Haggadah raised a very real question for medieval Jewry: If a Jew deliberately “goes over to the other side,” is he still a Jew? The illumination, which shows Datan and Aviram as figures with bird-like “Jewish” features but without the Judenhut, answers the question: Jewish identity is inescapable.

Datan and Aviram were not captives like Joseph, nor were they enslaved against their will like their fellow Israelites. Rather, they willingly went over to the enemy side. They represent another category in the social world of medieval Jewry, the convert, mumar or meshumad. It is obvious that these figures are not part of the Jewish community. Nonetheless, they are Jews, in accordance with the principle that though a Jew may sin, he remains a Jew.

What we are witnessing here is a recognition on the part of Ashkenazic patrons and their artists that rabbinic tradition might have “protested too much” about the piety of some biblical figures. Medieval Ashkenazic Jews were familiar with Jews who worked for the government, Jews who were impoverished, and Jews who left the community, and they adjusted their depiction of the Exodus story accordingly. In doing so, they were creatively fulfilling their obligation to regard themselves as if they had personally come out of Egypt.

The biblical commandment concerning the eve of the Seder is that “you shall tell your child [of the Exodus],” to which the rabbis added “anyone who expands upon the telling of the Exodus from Egypt, is indeed praiseworthy.” The illustrations of the Haggadah are indispensable expansions, welcome windows into the lives of the people who commissioned, and in some cases created, them. And when I study them with my children, when I gain insight from their fresh and unjaded eyes, I understand the paraphrase of the rabbis’ mandate inscribed by Abraham of Ihringen, Germany in the Haggadah he illuminated in 1732: “Everyone who expands upon the scribal illumination and the illustration of the Exodus from Egypt is indeed both praiseworthy and superb!”

Suggested Reading

The Jewsraeli Century

Ben-Gurion declared that “with the creation of the state, we are standing on the edge of a new era. Not only in the life of the Jewish community in Israel, but . . . in the history of Judaism itself.” He was right, but not in the way he thought he would be.

The Rebbe and the Yak

What do you do when your ancestor appears to you in a dream saying that he is trapped inside the body of a Tibetan yak? If you're the Ustiler Rebbe in Haim Be'er's new novel, you go to Tibet to find him, of course.

A Plague on the Shores of the Sea of Galilee

The death of the Great Maggid in December 1772, a week before Hanukkah, was a crucial moment in the early history of Hasidic movement.

A Life with Consequences

Yitzhak Rabin was a realist who saw peacemaking not as the source of security but as a further development that needed to be based upon security.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In