Context and Content

The appearance of Eric Alterman’s new book could scarcely have been better timed. With the formation for the first time of an Israeli government including undisguisedly Kahanist elements, there is good reason to fear that Israel’s actions will soon induce more and more Americans, and American Jews in particular, to echo Alterman’s title: we are not one (with you Israelis). If, as Thomas Friedman—an American Jewish liberal Zionist if anyone is—wrote already in November in the New York Times, “the Israel we knew is gone,” then more and more of Israel’s American Jewish supporters are likely to drift away from it too, as Alterman already has.

Israel is a cause for which Alterman was once willing to fight. Less than a decade has passed since he tangled in the pages of the Nation with Max Blumenthal, the author of a briefly notorious anti-Israel screed. Highly critical of Israel’s policies himself, Alterman nevertheless called Blumenthal’s book a “carelessly constructed case against the Jewish state” and lambasted him for his failure to show any interest in “the larger context of Israel’s actions” and for his lack of evenhandedness.

Alterman was, to be sure, something less of a defender of Israel than he was of Israel’s doves. Now, however, he has all but completely lost confidence even in them—and has gone on to produce a book with some of the same flaws as Blumenthal’s.

The brief historical account of Zionism with which We Are Not One begins is almost too perfunctory and disorganized to deserve attention, but it is nevertheless revealing. Alterman explains Theodor Herzl’s transformation into a Zionist as a response to the demoralizing “antisemitic fury” directed in Paris against the alleged spy Alfred Dreyfus. This is a well-known biographical myth, and Jacques Kornberg, Shlomo Avineri, and others have demonstrated that Herzl was not particularly moved by the anti-Dreyfus outbursts at the beginning of 1895. He was, however, profoundly affected by the pervasive antisemitism he witnessed throughout Europe—the racism, the implacable prejudice, the discrimination—especially in Vienna, where he lived. Alterman, for his part, gives his readers very little sense of the true magnitude of “the Jewish problem” in Herzl’s day.

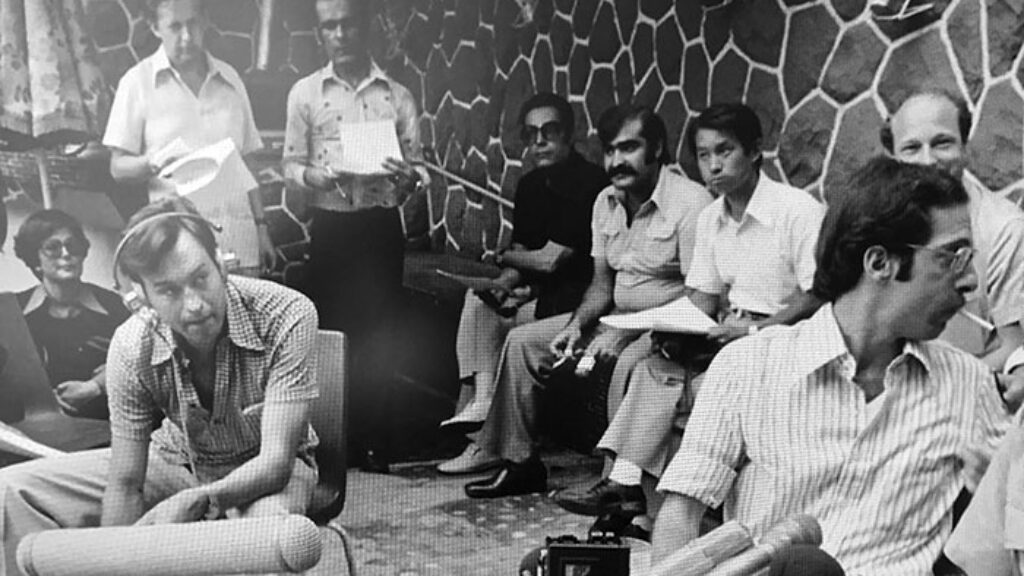

Israeli troops pass destroyed Egyptian vehicles on return to Israel during the Sinai campaign, December 1956. (Courtesy of the National Photo Collection, Israel.)

Alterman’s clumsily potted history eventually goes on to accuse American Zionists of having abandoned “the desperately difficult cause of ‘rescue’” of European Jewry during World War II because that effort “could not compete with the thrilling potential of the first Jewish state in nearly two millennia.” The idea that Zionism has been a vicarious distraction for American Jews is a recurring theme of Alterman’s book. Perhaps this is why he finds their wartime prioritization of Palestine at this time “sometimes difficult to forgive,” even though he recognizes the likely futility of Jewish efforts to enlist the help of an America that was completely unwilling to act on behalf of the Jews of Europe.

Alterman voices no disapproval, on the other hand, of American Jews who chose at that time not to “hop aboard the Zionist express.” His description, for instance, of Elmer Berger, the Reform rabbi who headed the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, contains no note of criticism, despite the fact that Berger’s organization denounced “the Hitlerian concept of a Jewish state”—in the middle of World War II.

It seems as ifAlterman’s latter-day rejection of Israel has led him to a rather jaundiced reassessment of the Zionist project as a whole. It has certainly hardened his judgment of the Jewish state’s early years and rendered him guilty of overlooking what he once called “the larger context of Israel’s actions.” While he dwells extensively on Israel’s responsibility for the creation of the Palestinian refugee problem, he has very little to say about its concurrent absorption of vast numbers of Jewish refugees, including hundreds of thousands fleeing Arab lands. Nor does he note how many of the new immigrants were settled in border regions where they were regularly the victims in the years to come of cross-armistice-line attacks by Palestinian fedayeen.

Alterman does mention one such attack in October 1953, in which a Jewish mother and her two children were killed. He makes this exception because this raid led to a notoriously brutal Israeli retaliation against Qibya, a West Bank village, that is remembered to this day in most Israeli quarters as a lamentable abuse of power. This incident, he says correctly, was one of the worst to take place. But Alterman is mistaken when he says that “the young state’s frequent military operations against its neighboring Arab nations cost the country 1,237 lives, and far more than that among their victims.” It would have been helpful, to begin with, to note that Israeli military operations undertaken at this time were almost all attempts to deter cross-border infiltration. And where, I wonder, did he get this utterly inaccurate figure? He certainly didn’t take it from the article by Benny Morris that he cites in the nearest footnote. Perhaps it represents a miscalculation of how many Israelis were killed by infiltrators (the total number of which, Benny Morris writes in one of his books, was around three hundred between 1951 and 1956), plus the Israeli soldiers killed in any kind of action between the end of the War of Independence and the end of the Sinai campaign (though that was fewer than five hundred). What is true, however, is that the number of Arabs who died as a result of Israeli military operations is unknown.

The relationship between the fedayeen attacks and Israel’s 1956 Sinai campaign is debatable, but this is not a subject that Alterman chooses to address. As far as he’s concerned, Israel’s “co-conspiratorial” attack with the French and British was the result of Egypt’s seizure of the Suez Canal and its shutting of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. He says nothing at all about the massive Soviet arms deal with Nasser in 1955 that, more than anything else, inspired Ben-Gurion to launch a preemptive attack on Egypt. Omitting any reference to such calculations is, of course, precisely ignoring the historical context, and is a way to make Israel look more mercenary than self-protective.

Even more important, for Alterman’s purposes, than exposing some of what he regards as Israel’s original sins is explaining why the country managed despite them to maintain a positive image among Americans, and among American Jews in particular. Rather than telling a complex story about religion, politics, and culture, Alterman focuses on the 1958 bestseller by Leon Uris, Exodus. He doesn’t discuss the novel in any detail, but he does say what he thinks is wrong with it: apart from being of poor literary quality (a judgment with which no one can disagree), it is historically inaccurate (as Alterman is not really entitled to complain).

The 1960 New York City premiere of Exodus, December 15, 1960. (Masheter Movie Archive/Alamy Stock Photo.)

Alterman blames the novel for idealizing and romanticizing the Jews who fought for Israeli independence as twentieth-century equivalents of the patriots who won the American Revolution—and for demonizing virtually all the Arabs with whom they had to contend. He is clearly disturbed by the way in which the book contrasts Israeli “freedom fighters” like the fictional Ari Ben Canaan (Paul Newman in the movie) with “diaspora wimps of yore,” and Alterman is caustic in his criticism of the Israeli politicians who were well aware of the novel’s flaws but only too happy to draw on the images it promoted.

But what he regrets the most is the broad, long-term success of these images. Take Jeffrey Goldberg, for instance, who, as Alterman notes, has described himself as having been set on “a course for Aliyah” and service in the IDF thanks to Uris’s novel. Goldberg eventually became the editor of the Atlantic, which, Alterman intones, is “one of the two or three most influential voices in the entire US media on the issue of Israel, often helping to define the parameters of what would be considered responsible discourse.” It is unfortunate, Alterman evidently feels, that someone naive enough to have been inspired by Uris has attained such a position, but he fails to note that in the very interview that he cites Goldberg himself regrets the fact that Exodus “created the impression that all Arabs are savages.” Goldberg goes on to say that “the lingering effects of [the book’s] sometimes-cartoonish portrayal of Israel’s founding can still be seen in the opinions of the more unthinking among Israel’s supporters.”

Alterman, for his part, sees the lingering and damaging influence of Exodus not just among Israel’s less sophisticated backers butall over the place. That influence was only magnified, he writes, by the occurrence of the Six-Day War in 1967, which left American Jews, who had witnessed the siege of Israel in May and early June, with a false sense of its vulnerability to the direst threats, and excessive admiration for, and vicarious identification with, the real-life Ari Ben Canaans—such as Moshe Dayan— who saved it.

We Are Not One contains a lengthy account of the relationship between the United States and Israel since the Six-Day War, intertwined with a blow-by-blow account of the post-1967 competition, between two camps, within the American Jewish community. The first camp, according to Alterman, consists of people seduced by false visions of a heroic and virtuous Israel, who have sought both to unite American Jews behind the Jewish state and to press the US government to support it, no matter what it does. The second is made up of the gradually increasing numbers of liberal-minded American Jews who have been disillusioned by what they see as Israel’s uncompromising stance and its oppressive occupation of the West Bank.

Alterman’s portrait of the ardently pro-Israel camp is a uniformly hostile one, and it is less than completely reliable. He knows, for instance, that the American Jewish Committee was for a long time quite cool toward Zionism and deduces from this fact that the magazine it published, Commentary, must have been consistently hostile to Israel until the Six-Day War. It was only in that war’s aftermath, he writes, that it “flipped 180 degrees and now basked in Israel’s military prowess.” This fits Alterman’s grand narrative but it’s not true. Browse through back issues of Commentary from, say, the Sinai campaign, which it covered sympathetically, to May 1967, and you’ll find plenty of strongly pro-Israel articles and nothing at all that smacks of animosity toward the country.

It is, however, Commentary’slast half-century as a neoconservative magazine that particularly bothers Alterman, along with Martin Peretz’s New Republic, AIPAC, and other pro-Israel American Jewish organizations. He seeks to show how neoconservatives in particular have been ready to endorse almost any Israeli exercise of power and to silence all efforts to criticize it.

[Neoconservative] success in the media and politics led to greater and greater avenues of influence in the Republican Party, where, together with the evangelical Christians and the generous contributions of a few extremely wealthy Jewish funders, they successfully converted the party to a militant version of Zionism that refused to entertain almost any compromise on Israel’s retention of “Judea,” “Samaria,” and most of all, an “undivided Jerusalem.”

Unlike so many others, however, Alterman does not blame Jewish neocons for the Iraq War. While he notes that many of them, in the press and in the government, were calling for US action against Iraq even before 9/11, he is extremely skeptical of the notion most famously voiced by Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer in their 2007 book The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy, that Jewish neoconservatives were the “critical element” in the decision to go to war in 2003. He notes that Walt and Mearsheimer “promised ‘abundant evidence’ on this point, but nowhere among their 1,399 footnotes did they make good on that claim.”

What the neoconservatives could not alter, Alterman reports, is the persistence of dovishness in the American Jewish population. Despite all their efforts, the Republican share of the Jewish vote has remained small, as did support for Israel’s settlement policy. The 1970s left-wing group Breira, which he discusses, was short-lived, but J Street, T’ruah, and Americans for Peace Now arose. Although Alterman regards the emergence of these organizations as relatively positive developments, he doesn’t explicitly endorse them. They are, it seems, simply too Zionist for him.

We Are Not One has almost nothing favorable to say about the State of Israel apart from some brief words of praise for Yitzhak Rabin’s efforts at peacemaking. This is either because Alterman genuinely believes there is nothing else that can be said in favor of the country or he doesn’t want to admit that there is. If the latter is the case, it may be because he wants to steer clear of yielding to pro-Israel pressure the way that Neera Tanden of the Center for American Progress did, by his account, some years ago. After the center’s website, Think Progress, published a series of posts and tweets critical of Israel and AIPAC, Ann Lewis, a “close adviser to Hillary Clinton, as well as a frequent speaker at AIPAC events . . . read Tanden the riot act about Think Progress’s treatment of Israel, accusing it of, among other sins, failing to balance its criticisms of Israel with compliments for its virtues.” Tanden, Alterman reports, buckled under. Maybe he wants to show that he won’t.

It seems more likely, however, that Alterman really believes that only people wearing Exodus-tinted glasses could possibly see much that is worthy of praise in the way that the Jewish state has conducted itself over the past seventy-five years. Moreover, he seems to be pleased by evidence that others are coming around to the same point of view. Although Joe Biden is a politician in the old mold, “below the presidential level, among Democrats, liberals, young Jews, and even young evangelicals, the foundations that had always undergirded America’s support for Israel had grown decidedly shaky.”

There are other liberals who have noted these developments, welcomed them, and seen in them reason to hope for a counterforce that could still have a constructive influence on Israel. But Alterman is no longer prepared to share such an outlook. He speaks, instead, of “an all but unbridgeable gulf” that has opened between Israelis, who are “moving further and further rightward,” and American Jews, who have “remained steadfast in their commitment to political liberalism.” If there is some remotely possible way of building a bridge over that gulf, Alterman offers no suggestions as to how it might be done. His only constructive thoughts about the Jewish future are of a different sort:

Clearly a reimagining of what it means to be a diasporic Jew is necessary if the community is to retain even a significant fraction of those drifting away from the faith, much less find a way to grow again. But American Jewish institutions’ relentless focus on—and demands for—fealty to Israel, tied to the Holocaust and antisemitism, are the only cards that mainstream Jewish leaders know how to play, and thus make any such renaissance difficult to imagine.

It’s not just fealty to Israel, however, that Alterman rejects. He rejects, it seems, any kind of support for it at all. Last spring, in a talk to a left-leaning audience at Tel Aviv University, he made explicit what is not completely spelled out in We Are Not One:

I’m sorry, I’m abandoning you and your colleagues. I’m going to devote my attention to rejuvenating American Judaism. Those are my people. I used to have in my will Israeli peace groups, I’m changing my will and I’m funding American Jewish scholarly and charitable institutions.

I can understand how a onetime liberal Zionist, frustrated by the trends of the past decade in Israel, can break ranks with the Jewish state, and American Judaism certainly needs rejuvenation. But this doesn’t give Alterman the right to recast Israeli history to suit his new convictions, or to impugn the motives, in facile and misleading ways, of Israel’s more constant—if not untroubled—friends. Viewed in a larger context than he is currently willing to provide, Israel’s actions reflect a mix of realpolitik, idealism (both pure and misplaced), brilliant strategy, and tragic error. And the story of American and American Jewish support for Israel is richer and much more complicated than the vicarious search for thrills that Alterman disdainfully describes.

Suggested Reading

And How Do You Like Israel?

The Six-Day War marked a critical turning point in the evolution of the Western world’s attitude toward Israel.

Could It Have Happened Here? The Implausible Plotting of The Plot Against America

Was America in 1940 primed for an antisemitic leader, as Roth and his adapters would have us believe?

Our Exodus

How did a high-school dropout named Leon Uris pen one of the most influential novels of all time?

The War on History

"People have often asked me if something like the revisionist Israeli historiography to which I contributed in the late 1980s exists on the Palestinian side."

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In