Our Exodus

Can any modern Jewish literary career have been less likely than that of Leon Uris?

Before dropping out of high school to join the Marines, he flunked English three times. After serving bravely and honorably against the Japanese at Gaudalcanal and at Tarawa, he did not take advantage of the G.I. bill and, unlike nearly four out of every five young Jews in postwar America, never went to college. Nor did he have a bar mitzvah ceremony and, as an adult never observed any Jewish holidays. Yet, in 1956, after having written two bestsellers set in World War II, Uris decided to write a novel about the origins of the State of Israel. Although he went on to write several more bestsellers, it is this novel, Exodus, that justifies two new scholarly books, M. M. Silver’s monograph on how Uris “Americanized” the story of the founding of the State of Israel, and Ira B. Nadel’s biography of the novelist.

The books highlight Uris’ peculiar status in 20th-century Jewish history. Neither Silver nor Nadel makes a case for the author’s literary importance and the news they bring of their subject’s simplistic attitudes and hard living will not enhance his reputation. Nonetheless, they provide the materials for a surprising reassessment of Uris’ historical importance.

Inscribed on Uris’ tombstone at the military base in Quantico are the twin markers of his identity: “American Marine/Jewish Writer.” The Marine Corps was the branch of the service that contained those Lenny Bruce had dubbed “heavy goyim.” Thanks to the Corps, Uris erased some of the shame that he attached to the misery of his struggling and fractious family. He especially needed to break free of a cantankerous father, an unsuccessful paper-hanger who had come to America from Poland via Palestine, and adhered to the Communist illusions promoted in the Yiddish daily, the Freiheit, all his life.

The Jewish inhabitants of Israel are “magnificent people,” Uris wrote his father in 1956, during his first visit. Here, the novelist added in an unsubtle rebuke, lives “a kind of Jew you and I have never seen before.” Out of that dichotomy came a determination to make American Jews proud of the achievements of a nation that would be celebrating the tenth anniversary of its birth in 1958. But the primary readership of Exodus was intended to be non-Jewish Americans—not merely because there were so many more of them, but also because Uris interpreted Zionism as a variant of the historic yearning for national liberation, a replay of 1776 (and from the same imperial foe, no less). Academics these days are quick to see everything as mediated, and both Silver and Nadel read Exodus as an Americanization of Middle Eastern history by the screenwriter of Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (which also played somewhat fast and loose with history). But his was also among the first American novels to expose the horror of the Holocaust, and he made explicit the essential moral connection between the vulnerability of European Jewry and the formation of a state that would end the history of pogroms, massacres, and, of course, genocide.

The Jewish inhabitants of Israel are “magnificent people,” Uris wrote his father in 1956, during his first visit. Here, the novelist added in an unsubtle rebuke, lives “a kind of Jew you and I have never seen before.” Out of that dichotomy came a determination to make American Jews proud of the achievements of a nation that would be celebrating the tenth anniversary of its birth in 1958. But the primary readership of Exodus was intended to be non-Jewish Americans—not merely because there were so many more of them, but also because Uris interpreted Zionism as a variant of the historic yearning for national liberation, a replay of 1776 (and from the same imperial foe, no less). Academics these days are quick to see everything as mediated, and both Silver and Nadel read Exodus as an Americanization of Middle Eastern history by the screenwriter of Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (which also played somewhat fast and loose with history). But his was also among the first American novels to expose the horror of the Holocaust, and he made explicit the essential moral connection between the vulnerability of European Jewry and the formation of a state that would end the history of pogroms, massacres, and, of course, genocide.

Deliberately divided, like the Pentateuch, into five parts, Exodus ends fittingly with a seder. After all, as Uris informed his father in 1956, “the Bible sold six million copies” a year earlier. Exodus could not quite match that kind of popularity, but its success was staggering. By February1959, Doubleday’s hardcover edition was selling 2,500 copies a day, flying off the shelves. By the end of that year, Bantam correctly guessed that the paperback edition might come close to selling five million copies, and therefore initiated what was then the largest advance print order in the history of publishing. The director of Israel’s tourist office observed “more tourists fly in to Tel Aviv with Exodus than with the Bible.” In 1960-1961, El Al offered a two-week tour for visitors to the Holy Land to see where (the fictional) Ari Ben Canaan and his comrades staged the exploits that promoted Jewish pride. Four decades later, Edward Said would complain to Al-Ahram saying, “the main narrative model that dominates American thinking still seems to be Leon Uris’ 1958 novel Exodus.”

Uris went on to write other books about Jews, whether set during the Holocaust (Mila 18, QB VII) or in the Middle East (Jerusalem: Song of Songs, The Haj, Mitla Pass). Even Trinity, his 1976 novel about Ireland, stemmed from his identification of the Irish Catholics with the Jews (with Great Britain, once again, as the enemy). Despite its intimidating 751 pages, Trinity stayed on the New York Times Best Seller List for one hundred weeks and sold more than five million copies. But Exodus was singular. Perhaps only The Good Earth is comparable, as an example of an enormously popular novel that decisively shaped American perceptions of a foreign country. But Pearl Buck knew China better than Uris knew Israel, and there was little about Uris’ background or interests that would have suggested a capacity for writing about the Zionist enterprise.

On this odd Jewish writer, Silver’s Our Exodus is more reliable than is Nadel’s Leon Uris, and exhibits a surer grasp of context. Silver is also more informative on the ways that Exodus diverges from the historical record. But Nadel’s biography, though more informal, is also the juicier of the pair, because its subject was so prickly a character and because his literary career was so improbable. Uris’ personality was as volatile as an ammo dump. His truculence, often fueled by vodka martinis, seems to have matched his father’s, but it was compounded by a litigiousness that Wolf Yerushalmi (who shortened his name to Uris only when he came to America) could not have afforded. Cocaine also took its toll. Uris eventually alienated nearly all his friends and close relatives, did not attend his father’s funeral, and was far too jealous to seek companionship or support among other writers, to whose work he generally remained indifferent or hostile. The bookshelves in the New York apartment where Uris’ last years were spent displayed no works other than those he himself had written. In fact, nothing made him more intemperate than discussing the work of his fellow Jewish American novelists. Even Marjorie Morningstar he denounced as “harmful to the best interests of the Jewish people.” This was hardly a literary judgment, but Uris did not—or could not—differentiate between the aims of Herman Wouk and Norman Mailer. These novelists, Uris complained, portrayed Jews either as unappealing alrightniks or as candidates for psychotherapy, or both. And when his own unabashed Jewish nationalism annoyed “the so-called liberal Jewish press,” Uris had a ready explanation: “Jews have always turned on their heroes.”

Nadel’s account of Uris’ final years does not make for edifying reading. He was overweight and suffered from high blood pressure, arthritis, knee pain, lower back pain, dental problems, and gout, among other ailments. As he aged, Uris often made loutish passes at married women and patronized prostitutes. One prostitute once beat him up so badly he was hospitalized; later, while with a Latvian masseuse whom he assumed to be a prostitute, Uris defied a “Do Not Touch” sign and got beaten up again. His lavish spending habits forced the former millionaire to beg for credit from his publishers. Such was the vulgarity of his mind that his mounting medical and personal problems led him to describe his tsures as an “emotional Auschwitz.”

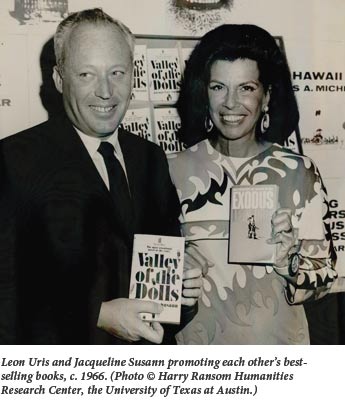

How to assess his legacy is a challenge that neither Silver nor Nadel fully meets. It is pointless to hold an openly commercial writer to formal or aesthetic standards to which he did not subscribe. For a quarter of a century beginning with Battle Cry in 1953 and ending with Trinity in 1976, Uris showed an uncanny knack for gratifying popular taste. A 1966 photo reproduced in Nadel’s volume portrays Uris with the author of Valley of the Dolls. But Leon Uris and Jacqueline Susann merit comparison only in terms of their sales figures. Uris did not appeal to prurient interest, or—it should be added—to that other staple of the mass market, the vicarious pleasures of violence. What haunted him instead was history: in the Pacific Theater, in the Middle East, in the Warsaw Ghetto, in the Nazi camps, and in Ireland. To be sure, Uris was a philistine, and would have agreed with Mickey Spillane, who once said “I don’t give a hoot about . . . [reading] reviews. What I want to read are royalty checks.” But unlike such bestselling contemporaries, Uris actually made a difference.

How to assess his legacy is a challenge that neither Silver nor Nadel fully meets. It is pointless to hold an openly commercial writer to formal or aesthetic standards to which he did not subscribe. For a quarter of a century beginning with Battle Cry in 1953 and ending with Trinity in 1976, Uris showed an uncanny knack for gratifying popular taste. A 1966 photo reproduced in Nadel’s volume portrays Uris with the author of Valley of the Dolls. But Leon Uris and Jacqueline Susann merit comparison only in terms of their sales figures. Uris did not appeal to prurient interest, or—it should be added—to that other staple of the mass market, the vicarious pleasures of violence. What haunted him instead was history: in the Pacific Theater, in the Middle East, in the Warsaw Ghetto, in the Nazi camps, and in Ireland. To be sure, Uris was a philistine, and would have agreed with Mickey Spillane, who once said “I don’t give a hoot about . . . [reading] reviews. What I want to read are royalty checks.” But unlike such bestselling contemporaries, Uris actually made a difference.

Thousands of readers wrote to thank him for making Jewish identity something to be cultivated rather than suppressed. Exodus was integral to the process of ethnic discovery (or rediscovery), and fortified the desire among countless American Jews to invoke not only the right to be equal but also the option to be different. In aiming primarily at non-Jewish American readers, Uris actually undershot his target. Exodus may even have helped invalidate the expectation of Herzl that the Diaspora was fated, whether by the pressure of persecution or the allure of assimilation, to vanish. Uris’ impact on American Jewry was truly extraordinary. Nor could the effect of the Russian translation of Exodus, which circulated in a samizdat edition, have been anticipated. Soviet Jews read this illicit edition as a guide to the buried treasures of their Jewish past. The executive director of the National Conference on Soviet Jewry, Jerry Goodman, claimed that Exodus affected the refuseniks even more than did the Bible. In a 1985 letter to this reviewer, Uris placed Exodus “among the most influential novels in history.” That opinion is astoundingly self-serving, but it is also incontestably true.

By changing the lives of American, Soviet, and former Soviet Jews, Uris expanded the boundaries of what a novel might be expected to accomplish. More than any other writer, he also helped Israel to win the crucial friendship of the United States. It worked both ways. Ari Folman, the Israeli filmmaker who made Waltz With Bashir, recently remarked that Uris’ novel “is a must-read in Israel.” Such are the elements of an utterly unpredictable legacy. By the same extra-literary standard by which he once dismissed Marjorie Morningstar, Leon Uris deserves to be ranked as the most important Jewish novelist who ever lived.

Suggested Reading

Religious Freedom and Jewish Experience

Religious liberty is back on the Supreme Court’s docket. The court should think carefully about what freedom of religion really means in different communities. Take Jews for instance . . .

The Adjectival Liberal and The Kingship of God

Michael Walzer is one of our great defenders of liberal democracy, but does his vision exclude religious Jews?

What They Talk About When They Talk About Golems

On golems and global conspiracy theories.

Inside or Outside?

After the discoveries of the Cairo Geniza and the Dead Sea Scrolls, scholars of Judaism slowly began to reconstruct the 400-year period separating the latest parts of the Hebrew Bible from the earliest rabbinic compilations.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In