Prince of the Lost Tribes

In the 1520s, a striking black man—the Italian-Jewish scholar Gedaliah ibn Yahya described him as “black as a Nubian (shahor ke-kushi)”—showed up in North Africa, claiming to be the son of a certain late King Solomon and the younger brother of King Joseph, who ruled a Jewish kingdom in the desert of Habor, somewhere in Arabia. His name was David Reubeni, and he described the three hundred thousand Jews ruled over by his brother as descendants of the biblical tribes of Gad, Reuben—hence Reubeni’s name—and half of Manasseh. According to Reubeni, they were at constant war with their Muslim neighbors. Consequently, King Joseph and his seventy elders had dispatched Reubeni on a mission to meet with the pope and to form an alliance with European Christendom in a new crusade against the Muslims.

This Jewish-Christian crusade would not only support Reubeni’s (possibly mythical) kingdom; it would also aid the European powers in their struggle with the Ottoman Empire (the Ottomans would lay siege to Vienna by the end of the decade). Of more interest to his Jewish audience, he planned to return Jews to dominance in Palestine. Reubeni’s apparently impressive diplomatic documents were signed not only by his brother King Joseph but by all seventy elders.

Although Reubeni never claimed to be the messiah, and in fact denied it, the nature of his mission as well as phrases and events scattered throughout his travel diary had a strongly messianic quality. Certainly, some of his followers and supporters took him as the messiah or his forerunner. Moreover, this was a time of messianic or millenarian fervor among Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Members of all three religions expected their respective redeemers to appear, or reappear, around the turn of the sixteenth century, each for complex reasons of their own.

Five hundred years after his sudden appearance in Europe, nobody knows who David Reubeni actually was or where he came from. Historians have argued variously that he was Indian, Abyssinian, Sephardi, Yemenite, a Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jew, or perhaps not really Jewish at all. As Alan Verskin remarks in one of the many excellent notes to his complete new translation of Reubeni’s diary, “Much fruitless effort has been expended to pinpoint Reubeni’s origins, which scholars have placed across the Old World.” (The manuscript of Reubeni’s diary might have contained some clue, but it was stolen from Oxford’s Bodleian Library in the late nineteenth century, leaving only a poor hand-traced copy for scholars to examine.)

In his diary, Reubeni tells the story of his journey through Africa, where he passed himself off as a sayyid (a descendant of Muhammad) before arriving in the Jewish communities of Egypt and Palestine to reveal his mission. From there he took a ship to Italy, where he recruited influential Jewish advocates and met with the great cardinal Egidio di Viterbo, who was a leading Christian kabbalist and millenarian. Egidio brought Reubeni to Pope Clement VII, who listened politely to Reubeni’s pitch to help reunite the warring European powers in preparation for a Christian-Jewish war in Ottoman Palestine.

The pope, who was in the midst of a power struggle with the Holy Roman emperor Charles V, said that he was unable to help Reubeni. However, he gave him a letter of support and sent him to visit King João of Portugal. Despite various troubles and opposition from both Jewish and Christian adversaries, Reubeni and the unruly retinue of Jewish supporters he had collected on his travels reached Portugal. There he eventually received some positive feedback from the king. Unfortunately for Reubeni, he also aroused great excitement among Portuguese conversos, those former Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity in 1497, and their descendants. This did not go unremarked by the authorities.

The final straw came when, in a moment of messianic fervor, a young converso courtier named Diogo Pires circumcised himself. Diogo declared himself a Jew under the name Solomon Molkho and fled the country for refuge in the Ottoman Empire. In Turkey, he became a famous kabbalist who influenced, among others, Rabbi Joseph Karo, the great mystic and author of the classic code of Jewish law, the Shulchan Arukh.

Meanwhile, Reubeni was forced to leave Portugal with nothing to show for his efforts. On the outward journey, he was shipwrecked in Spain, where he was held prisoner and all his documents were stolen. He eventually arrived in Mantua, where he clumsily attempted to forge replacements for his impressive letters from his brother and various illustrious supporters. The Jewish leaders quickly discovered this subterfuge and denounced Reubeni as a fraud.

In 1530 Reubeni reunited with Pires—now Molkho—his erstwhile acolyte, and the two joined together for a mission to see Emperor Charles V at Regensburg. It did not go well. It is not known what they discussed with the Holy Roman emperor, whether it was military support for a new crusade or their hope that the emperor would convert to Judaism, but Charles dispatched them both to the inquisitors in Mantua. Molkho was executed in 1532. Reubeni was then transferred to an Inquisition prison in Spain, where he was executed in 1538.

When Reubeni arrived on his remarkable diplomatic mission, the Western European Jewish communities that still existed were hanging by a thread. The Jews of Spain, Sardinia, and Sicily had been converted or expelled in 1492. Those of Portugal, including many of the Spanish exiles, were forcibly converted to Catholicism in 1497. The Jews of England had been forced out in 1290, those of France in 1306 and 1313, those of Provence in 1498, and those of various German and Italian states around the same time—Ravenna in 1491, Perugia in 1485, Parma in 1488, Milan in 1489, Halle in 1493, Salzburg in 1498, Nuremberg and Ulm in 1499, and so on. In addition to these expulsions, the Jews suffered from riots, blood libels, and host-desecration calumnies. It was in this miserable context that Reubeni appeared, declaring:

We are royalty and our fathers have been royalty in the desert of Habor since the Temple was destroyed. We rule over the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh in the desert of Habor. In the land of Kush [presumably Ethiopia], there are nine and a half tribes, who are also ruled by kings. . . . I am a greater sinner before God than any one of [the Jews of Fez]. I have killed many people. In a single day, I once killed forty enemies. I am not a sage or a kabbalist, neither am I a prophet or the son of a prophet (Amos 7:14). I am merely an army commander. I am the son of King Solomon of the line of David son of Jesse.

Merely an army commander? The Jews had plenty of sages and kabbalists, but a Jew descended from the kings of Israel, commanding a Jewish army and playing international power politics, was an extraordinary source of hope.

Reubeni himself was ill-tempered, perhaps from his frequent fasts, and quick to resort to violence, which itself was remarkable. In Portugal, where he was keenly aware of the precariousness of his position as a Jew, he nevertheless insisted on being treated with respect, even by the king. When a monk insulted him, saying “that there was no King of Israel and that we had no claim to royal lineage,” Reubeni promptly defenestrated him:

He was standing in front of a big window and I, filled with God’s zeal, threw him out the window in front of all the gentiles, who laughed at him and were afraid to speak against me.

Reubeni’s fearlessness recalls a roughly contemporary incident in Egypt, at the home of the nagid (communal leader) Isaac ha-Kohen Solal, as recorded in Aaron Ze’ev Aescoly’s Jewish Messianic Movements. An African Jew who had been redeemed from captivity was staying with Solal when he was robbed:

One time four robbers came up onto our roof. We [members of the household] were very terrified, but this guest said to them, “Why have your faces fallen?” They explained the matter to him. He immediately grabbed a sword in his hand, jumped onto the roof alone, and like a lion, made them flee for their lives. He said to [the nagid’s family], “Even ten are like just one in my eyes, because every single day we kill a bunch of [enemies] when they come to make war on us.”

Such fierce, fearless black Jews, seemingly descended from the lost tribes, were a foil for diasporic Jewish hopelessness and powerlessness. (It should be noted that some historians have speculated that Solal’s guest was Reubeni himself.)

Of course, some nervous community leaders thought Reubeni a dangerous provocateur, if not a charlatan. Rabbi Abraham ben Solomon Dienna of Mantua denounced him: “No one has come to oppose us, rage against us, and cause us to perish, God forbid, like this enemy and adversary—this evil Haman,” who deserved, he said, to be put to death. Dienna’s position was apparently not a popular one, however. Hope has often trumped stability.

In his introduction and notes, Verskin does a terrific job of presenting both Reubeni’s itinerary and a sense of the historical and political background that made his adventures possible in 1520s Europe. He explains the relationships between the various kings, the Holy Roman emperor, and the pope. He clarifies the state of geographical awareness in the age of discovery and its relationship to politics, helping the reader understand the often warm, credulous reception given to a sketchy black Jewish emissary in the courts of Europe. He notes, for instance, that “Reubeni was not the first to present Christian rulers with the possibility of a non-Christian ally against the Muslims. . . . Christopher Columbus had justified his famous voyage to the Spanish monarchs as a quest to make contact” with another such mythical figure known as the “grand khan.”

There were several ways in which Verskin could have approached this project. The material is so rich that he could have produced an updated English version of Aaron Ze’ev Aescoly’s thick, heavily annotated and augmented 1940 Hebrew edition of the diary. But this would have been the work of several decades. On the other hand, he could have given us a bare translation with minimal apparatus. This small, elegant volume, which features Verskin’s rich thirty-page introduction and deft, helpful endnotes, seems just right.

Scholarly work on David Reubeni appeared throughout the twentieth century, and Kafka’s friend Max Brod published a historical novel in 1925 in which Reubeni was depicted as a kind of proto-Herzl playing world politics without a state. But most of the important work on Reubeni was concentrated in the 1940s and 1950s. Apparently, the figure of a deus ex machina savior from the lost tribes spoke to a generation overwhelmed by its own dialectic of helplessness and hope.

Suggested Reading

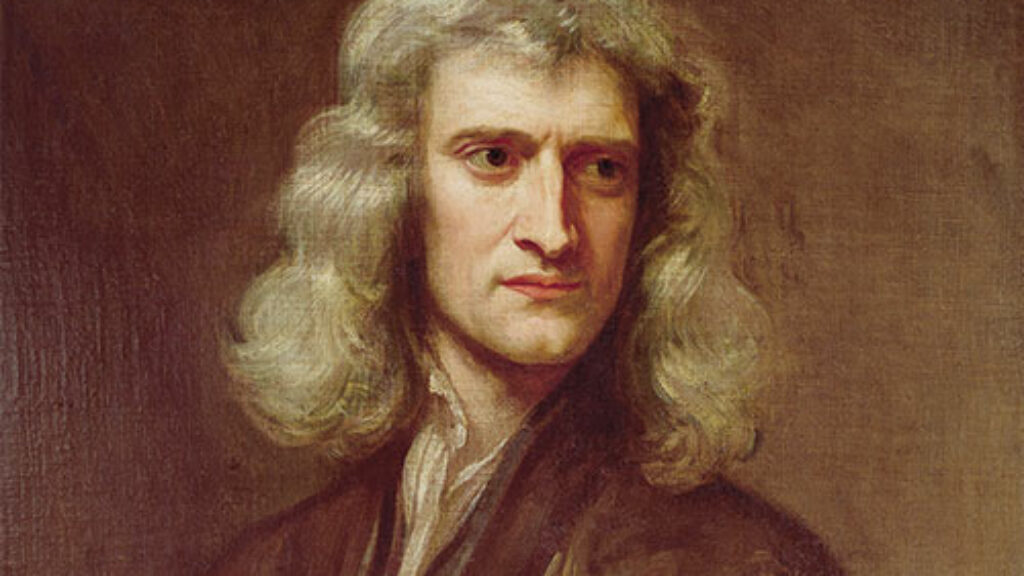

Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions

It takes a bit of a genius to successfully study a genius, and in this case one must first master the millions of words Isaac Newton wrote about natural theology, doctrine, prophecy, and church history.

Insiders and Outsiders

The Jewish sect that rejected cholent.

Secularism and Sabbateans

How did the Jews become modern? Three new books trace the roots of Jewish secularization.

Like a Son of Man

Who gets to anoint the Messiah?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In